По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

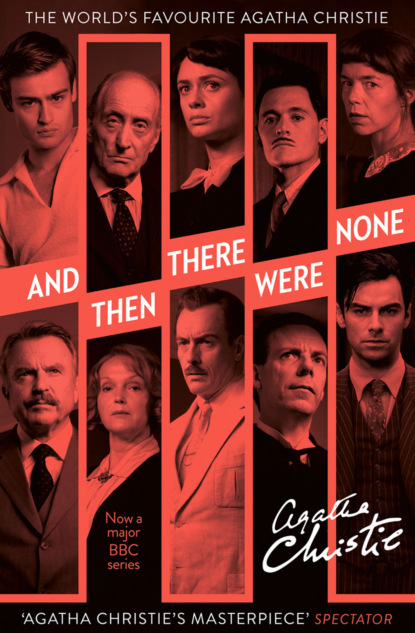

And Then There Were None

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I’m a good cook and Rogers is handy about the house. I didn’t know, of course, that there was to be such a large party.’

Vera said:

‘But you can manage?’

‘Oh yes, Miss, I can manage. If there’s to be large parties often perhaps Mrs Owen could get extra help in.’

Vera said, ‘I expect so.’

Mrs Rogers turned to go. Her feet moved noiselessly over the ground. She drifted from the room like a shadow.

Vera went over to the window and sat down on the window seat. She was faintly disturbed. Everything—somehow—was a little queer. The absence of the Owens, the pale ghostlike Mrs Rogers. And the guests! Yes, the guests were queer, too. An oddly assorted party.

Vera thought:

‘I wish I’d seen the Owens… I wish I knew what they were like.’

She got up and walked restlessly about the room.

A perfect bedroom decorated throughout in the modern style. Off-white rugs on the gleaming parquet floor—faintly tinted walls—a long mirror surrounded by lights. A mantelpiece bare of ornaments save for an enormous block of white marble shaped like a bear, a piece of modern sculpture in which was inset a clock. Over it, in a gleaming chromium frame, was a big square of parchment—a poem.

She stood in front of the fireplace and read it. It was the old nursery rhyme that she remembered from her childhood days.

Ten little soldier boys went out to dine;

One choked his little self and then there were Nine.

Nine little soldier boys sat up very late;

One overslept himself and then there were Eight.

Eight little soldier boys travelling in Devon;

One said he’d stay there and then there were Seven.

Seven little soldier boys chopping up sticks;

One chopped himself in halves and then there were Six.

Six little soldier boys playing with a hive;

A bumble bee stung one and then there were Five.

Five little soldier boys going in for law;

One got in Chancery and then there were Four.

Four little soldier boys going out to sea;

A red herring swallowed one and then there were Three.

Three little soldier boys walking in the Zoo;

A big bear hugged one and then there were Two.

Two little soldier boys sitting in the sun;

One got frizzled up and then there was One.

One little soldier boy left all alone;

He went and hanged himself and then there were None.

Vera smiled. Of course! This was Soldier Island!

She went and sat again by the window looking out to sea.

How big the sea was! From here there was no land to be seen anywhere—just a vast expanse of blue water rippling in the evening sun.

The sea… So peaceful today—sometimes so cruel… The sea that dragged you down to its depths. Drowned… Found drowned… Drowned at sea… Drowned—drowned—drowned…

No, she wouldn’t remember… She would not think of it! All that was over…

VI

Dr Armstrong came to Soldier Island just as the sun was sinking into the sea. On the way across he had chatted to the boatman—a local man. He was anxious to find out a little about these people who owned Soldier Island, but the man Narracott seemed curiously ill-informed, or perhaps unwilling to talk.

So Dr Armstrong chatted instead of the weather and of fishing.

He was tired after his long motor drive. His eyeballs ached. Driving west you were driving against the sun.

Yes, he was very tired. The sea and perfect peace—that was what he needed. He would like, really, to take a long holiday. But he couldn’t afford to do that. He could afford it financially, of course, but he couldn’t afford to drop out. You were soon forgotten nowadays. No, now that he had arrived, he must keep his nose to the grindstone.

He thought:

‘All the same, this evening, I’ll imagine to myself that I’m not going back—that I’ve done with London and Harley Street and all the rest of it.’

There was something magical about an island—the mere word suggested fantasy. You lost touch with the world—an island was a world of its own. A world, perhaps, from which you might never return.

He thought:

‘I’m leaving my ordinary life behind me.’

And, smiling to himself, he began to make plans, fantastic plans for the future. He was still smiling when he walked up the rock cut steps.

In a chair on the terrace an old gentleman was sitting and the sight of him was vaguely familiar to Dr Armstrong. Where had he seen that frog-like face, that tortoise-like neck, that hunched up attitude—yes and those pale shrewd little eyes? Of course—old Wargrave. He’d given evidence once before him. Always looked half-asleep, but was shrewd as could be when it came to a point of law. Had great power with a jury—it was said he could make their minds up for them any day of the week. He’d got one or two unlikely convictions out of them. A hanging judge, some people said.

Funny place to meet him… here—out of the world.