По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

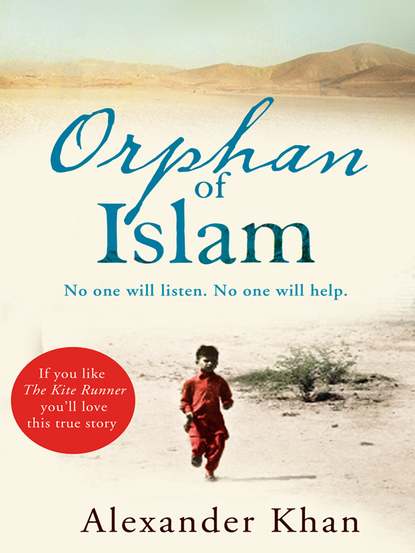

Orphan of Islam

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Finds out what?’ Fatima was standing at the kitchen door, glaring at her 15-year-old daughter. She must’ve been listening in when Ayesha was singing.

She turned to me. ‘What’s she been saying to you? Tell me.’

‘I dunno,’ I said, trying not to look at Ayesha. ‘I couldn’t understand it.’

‘Of course you couldn’t,’ Fatima said sarcastically. Then she pointed at Ayesha. ‘If I catch you singing that rubbish again, I’ll put you out of this house. Nice Pakistani girls don’t sing. Is that clear?’

Ayesha looked at the floor, then silently turned her back on her mother and stirred the contents of the pot.

‘Upstairs, you two,’ Fatima said to me and Jasmine, ‘and I’ll show you where you’re sleeping. It’ll be a squash, but you’ll just have to get used to it.’

The house was tiny: two rooms and a kitchen downstairs and two bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs. For a couple with one child, it would’ve been just about adequate. But not for two adults and seven children. Yasir, Fatima and Dilawar’s elder son, slept in the downstairs front room. He was due to get married in a few months and would then move out, but for the moment he was living at home and working in the family shop with his dad. Fatima and Dilawar slept in the front bedroom upstairs. The back bedroom was shared by Ayesha, Tamam, Majeeda and Maisa. And now there were two more occupants.

Fatima indicated Tamam’s bed. ‘You’re in there,’ she said, ‘and your sister can get in with Majeeda and Maisa. Yes?’

Jasmine pulled at my sleeve. ‘I don’t like it here, Moham,’ she said. ‘It smells funny. I don’t want to share a bed. Why can’t we go with Dad?’

‘Because you can’t,’ snapped Fatima in her shrill high-pitched voice. The tone of that voice, forever shrieking and shouting around that tiny house, would grate on me in the months ahead. Even now, if I close my eyes I can still hear it, like fingernails going down a blackboard.

‘This isn’t a hotel,’ Fatima continued, ‘despite what your father seems to think. Anyway, he’s not going to be around for a while, so I’m in charge. And in this house, what I say goes. Got it?’

We nodded meekly.

Fatima threw our pathetic little suitcases onto the beds. ‘Dinner will be ready in 10 minutes,’ she said, walking out of the bedroom. ‘Get your hands and faces washed now.’

That first evening in Nile Street was awful. Dilawar and Yasir knew we were coming to stay, but made no effort to make us feel welcome when they arrived home from the shop. All they wanted was their dinner, and they didn’t seem at all happy to have to share it with two new mouths on the other side of the table. But Dad was there, so they said nothing. Fatima was all smiles in front of Dad, reassuring him that of course she’d look after us and yes, we’d be fine staying there and the other kids would love to have two new people to play with. The sly looks and digs in the ribs we were getting from around that cramped table suggested otherwise. Only Ayesha seemed to understand how weird it felt for us to be back in England. She rubbed our heads and gave us extra little pieces of chapati when she thought no one was looking.

‘We might make a half-decent Pakistani wife out of you after all,’ commented Fatima, who had noticed the extra attention she was giving us.

When the meal was over, the men and a few of the children, me and Jasmine included, sat in the back room. Fatima, Ayesha and Majeeda stayed in the kitchen to clean up. The men lit cigarettes, sat back on the settees, which faced each other along two walls, and chatted among themselves. There was no TV set, so we played on the floor.

After a while, Dad stood up. ‘Time I was off,’ he said, looking at his watch.

He bent down and kissed us both.

‘Now, you two behave for your Aunty Fatima and Uncle Dilawar,’ he said. ‘I’ll be gone for a few weeks now. I’ve got some work on. Remember, be good. No playing up.’

He shook hands with Dilawar and Yasir and shouted a goodbye to Fatima. The front door banged and he was gone.

Again we were alone. With family, yes, but without the parents we needed and wanted to hold us, look after us, keep us safe.

The false smile Fatima had put on for Dad soon disappeared. The shrill tone was again present in her voice when she ordered us all upstairs to get washed and changed for bed. There were the usual bedtime moans and groans from her children, but Fatima was having none of it. We were hustled up the narrow staircase to the bedroom, Tamam and Majeeda leading the charge.

Majeeda was first into the bathroom, banging the door. Tamam stood outside, shouting and shouting for his sister to hurry up. In the bedroom, Maisa flung Jasmine’s suitcase on the floor and climbed onto the bed, stretching out her legs in a defiant display of ownership. Finally, Majeeda left the bathroom and got into bed, pushing Maisa against the wall. There was barely a ruler’s width of space for poor Jasmine. She looked at me with frightened eyes and I squeezed her hand. I was just as afraid, but didn’t want to let her know.

Tamam came into the room. He looked as though he’d rather share a bed with a crocodile.

‘Get in,’ he ordered, ‘and move right up. If you even breathe, I’ll boot you one!’

I did as I was told and squeezed myself as far as I could against the wall. I stared at the cheap torn lime-green wallpaper for as long as possible until the light went off. I was tired from the long flight and journey up from Heathrow, and soon fell asleep. Less than an hour later the light pinged on again. There was no lampshade, and the bare bulb seemed to penetrate every corner of that tiny claustrophobic bedroom.

‘Who’s nicked my radio?! Come on, you’re not going back to sleep till you tell me!’

Ayesha was furiously rummaging under beds, pulling sheets off sleeping children and pushing their tousled heads roughly aside so she could look under the pillows. Maisa started to wail and was quickly silenced by a thump in the guts from a grumpy Majeeda. Jasmine fell out of bed in the chaos, landing on the floor with a heavy thud. She started to cry. Tamam shouted at his oldest sister that he hadn’t got it.

The noise brought Fatima to the foot of the stairs.

‘What’s going on?!’ she screamed. ‘Get back in those beds and go to sleep. If I hear any more noise, I’ll come up there and beat the lot of you!’

Instantly there was silence and I knew she meant what she said.

Ayesha stood in the middle of the room, still looking for the missing radio. Then she crouched over Tamam and whispered within an inch of his face, ‘So if you haven’t nicked it, you thieving little sod, who has?’

Tamam smiled. ‘Better ask Mum,’ he said. ‘I think she’s got the answer to that.’

Ayesha’s face fell. Fatima must’ve heard her in the kitchen telling us about the radio. ‘What am I gonna tell Parveen?’ she muttered to no one in particular. ‘That was her radio. She lent it me. Mum’ll have binned it by now. Parveen’s going to kill me.’

‘Should’ve thought of that,’ said Tamam. ‘Now put the light off, will you?’

Ayesha yanked the cord and we were in darkness again. Tamam wriggled around until he was comfortable, not caring that I was on the receiving end of his feet and elbows.

Finally the room settled down and I dozed off. Tamam, too, relaxed and I could hear snoring from Ayesha’s side of the room. The younger girls had also nodded off at last. Until …

‘BZZZZ! BZZZZ!! BZZZZ!!! BZZZZ!!!!’

I sat bolt upright, looking round in terror. Something was wrong with the bed. It seemed to be alive, humming and buzzing as though a nest of angry wasps hiding in the mattress had been disturbed. I shook Tamam as hard as I could and tried to clamber over him to get out. In response he pulled himself up, crawled out of bed and pulled the light cord. Everyone woke up. Ayesha chucked a pillow in his direction and pulled her eiderdown over her head. Tamam leaned under the bed and unplugged something. Immediately the noise stopped. Then he pulled at the sheet on top of the mattress and from underneath it yanked out a thick grey blanket with an ominous dark stain spread right across it.

‘I piss the bed,’ he said simply. ‘I do it every night. If you’ve got a problem with that, lie on the floor. Otherwise shut up.’

I hadn’t said a word. Ayesha leaned over and clicked the light off. The mattress was soaked through and I could feel cold pee all over my legs. Horrible, but not so bad if it’s your own. If it isn’t – disgusting. I turned to the wall and started to cry. Was this what life was going to be like at Aunty Fatima’s?

In the days and weeks that followed, I discovered that the answer was ‘yes’. 97 Nile Street was cramped, chaotic, often violent (when Fatima delivered the slaps she’d promised on that first night) and always noisy. It’s the noise I remember most – the screaming, shouting, bickering, pushing and shoving that inevitably goes on when too many people are packed into a small space. Nile Street was less of a home and more of a crowd, especially when the daily procession of ‘aunties’ and their children came knocking on the door. True to his word, Tamam pissed the bed every night and mostly slept through the terrible wake-up call of his blanket alarm. Fatima was occasionally woken by it and would come into the bedroom screeching and shouting at us all to get up while she changed the sheets. Every night involved some kind of disturbance. Within a few days I went from a happy, playful child to a withdrawn creature with dark rings around his eyes who craved his own space and spent hours loitering in the alley behind Fatima’s backyard.

That said, Tamam wasn’t the bully I had him down for on that first night. He turned out to be a nice enough lad, and although he was a couple of years older than me, he didn’t resent me being in the house and even seemed to be pleased to have someone to knock around with.

I didn’t bother much with the younger girls; they did their own thing and that was fine by me. Ayesha was kind to both Jasmine and me, but seemed to be spending more and more time in the kitchen or sweeping the backyard. There was talk of marriage to a man from Pakistan. Ayesha would go ‘home’ for the wedding, then come back to live here with her new husband. Her British-born status guaranteed his residency. Was she happy about this? Being so young, I found it hard to know, but I do recall that she would regularly stand on the windowsill in the front bedroom, talking through the unlatched window to other teenagers – boys included – on the street. Sometimes Fatima caught her at it and gave her a big dressing-down in front of the whole family. Talking to boys was ‘shameful’, she insisted, and was bringing dishonour on their good name around Hawesmill.

‘Do you want to get married,’ she screeched, ‘or are you going to stay on the shelf forever? Because that’s the way you’re going!’

Ayesha was 15 at the time – stupidly young by Western standards for any talk of marriage, or even engagement. But in Pakistan it wasn’t uncommon to find girls half her age in that position. Besides, Yasir was 17 and he was due to get married soon. It was only right that Ayesha should be next.

The front room of the house was Dilawar’s little kingdom. He used it as a kind of storeroom for the shop, particularly for valuable and easily-stolen items like cigarettes, and we were never allowed in. Often he would take in his Pakistani newspaper and lock the door behind him, pleased to be away from the noise. He couldn’t escape the smell of curry, though, which percolated every room. There was always something bubbling away in a pan on the stove – just as well, given the number of visitors the house received and the odd times of day or night that Dilawar and Yasir would arrive home.

Generally, Dilawar was a kind and quiet man who would only flare up when Tamam was misbehaving. Then he’d beat him severely, leaving the rest of us in no doubt that he would do the same to us if we played up.

One of the highlights of the week was when Dilawar and Yasir came home from the shop with bags full of loose change. They’d pour it all over the low table in the back living room and ask us children to help count it. My cousins were surprisingly good at this, given their age and the fact that attending school wasn’t high on the list of priorities in Nile Street. They’d count out piles of coppers and silver, putting them to one side when they’d reached a pound’s worth. Yasir or Dilawar would then bag them up, £10 per bag. As far as I could tell, they didn’t have a bank account (it’s considered un-Islamic to trade with high street banks that have interest rates) and so all the money was kept in the locked front room. That’s what passed for family entertainment in that house.

As time went on and Dad’s visits became fewer, Fatima took less trouble to disguise her feelings towards us. She’d never been what you might describe as ‘warm’, but she definitely got worse. She screamed and shouted endlessly and it always seemed to be me who provoked it. Many times she raised her hand, and while she never hit me or Jasmine, the threat was clear. Perhaps she was afraid that we’d tell Dad and she’d get in trouble. Her problem was that she couldn’t see us simply as her brother’s kids. We also belonged to ‘that Englishwoman’, the woman who’d entered this close-knit family and taken her brother away. That he’d betrayed his Western wife and taken her kids abroad didn’t count; Fatima seemed to believe we were tainted with kuffar blood and would always remain outsiders. So why didn’t she and the family set us free? The logical decision would’ve been to return us to our mum. But there was something about this family that made it impossible for them to let go. We would have to stay among them until all traces of Western influence were removed.