По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

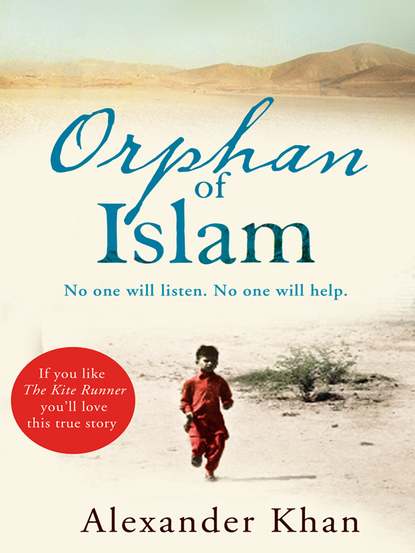

Orphan of Islam

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But if we were out of sight, we were out of mind. So Fatima created a special punishment for Jasmine and me. If we’d been naughty we were marched upstairs, pushed into the back bedroom and locked in. Occasionally it was both of us, but more often than not, I was alone. I think Fatima knew that Jasmine was young enough to be ‘re-educated’ effectively. She was also female, which carries its own status in Muslim culture. I was a different matter. Perhaps Fatima saw that I would not be so easily moulded. Whatever her reasons, I found myself spending hours in that locked room, staring out over the grey slate rooftops of Hawesmill and wondering what I’d done that was so wrong.

There were times when Jasmine and I clearly hadn’t done anything wrong, but were locked in the bedroom anyway. One minute we would be playing with our cousins, the next Fatima would be whisking us upstairs as the whole house erupted in frenzied activity, children and adults running and shouting everywhere. As we were rushed up, I was sometimes certain I could hear the sound of the letterbox flapping at the front door, accompanied by a woman’s voice yelling through it. When this happened, the door was never, ever opened, and yet normally a constant stream of visitors walked over that threshold at all times of the day. What was so wrong with this particular visitor that they could not be admitted?

We ourselves weren’t allowed out of the house very much. A walk to Dilawar’s shop with Fatima or Ayesha was as far as we got. There were no trips to the park, the playground or the seaside. We didn’t go into the town. Our whole life was 97 Nile Street and a couple of streets around it. We didn’t even go to school. Now I wonder why no school inspectors were on Fatima’s tail, but maybe back then they didn’t care whether Asian kids attended or not. However, we were getting an education of sorts at a house at the back of Nile Street that had been knocked through into the house next door and converted into a mosque.

Sebastopol Street was the home of the local imam and his wife. The mosque itself was only for men and older boys, so, with Jasmine, Tamam and Maisa, plus a handful of other little kids from around Hawesmill, I went along several times a week to sit in a side-room and learn the basics of Arabic, making a start on the 114 chapters of the Qu’ran. The imam’s wife took the lessons, handing out simple little textbooks which taught the ‘ABC’ in Arabic, plus other key words and phrases. As we made our first clumsy attempts at this complicated language she listened to us in silence, constantly playing with a set of worry beads. She taught us sentences that form the cornerstones of the Holy Book, for example:

Bismill

hi r-ra

m

ni r-ra

m

Al

amdu lill

hi rabbi l-’

lam

n.

which translates as:

‘In the name of God, the most beneficent, the most merciful,

All appreciation, gratefulness and thankfulness are to Allah alone, lord of the worlds.’

From an early age all Muslims know these verses from the opening of the Qu’ran, and I was no exception. I’d heard them spoken while in Pakistan. But I found it very difficult to read basic Arabic and also to get the correct pronunciation. The imam’s wife would listen to my tongue twisting all over the place and, with an expression like vinegar, hit me with a short stick she kept under the seat. She didn’t do it very hard – it was more of a tap than anything else – but it was enough to make me anxious. It also had the opposite effect to that intended: instead of learning to read and speak the verses properly, I became more word-blind and tongue-tied. From that moment on, I struggled with the Qu’ran. It would cause me no end of problems as my childhood progressed.

Chapter Three

After ten months at Fatima’s I’d become used to Dad coming and going. He would disappear for weeks on end and although I missed him at first, especially as Fatima obviously had it in for me, his absence wasn’t so noticeable day by day. What was becoming annoying was Tamam’s constant teasing about my ‘white Mum’. It was childish stuff but it hurt, especially when I was locked in the bedroom for retaliating. In there, the same old questions would go round in my mind. Where was she? Did she know we were here? When would she come for us?

The last question was the one I thought about most. As time went on and she didn’t appear, I wondered if she’d forgotten us or had found some other kids to be mum to. I must have asked Fatima loads of times about her (and, judging by Tamam’s teasing, it was obviously a topic for family discussion when we weren’t listening), but she constantly stonewalled me.

In the end, the knock on the door that saved us from a life of punishment and drudgery at Fatima’s came not from Mum but from Dad. He appeared one afternoon in late autumn, looking well-fed and satisfied with life. He stepped into 97 Nile Street with a big smile on his face and picked up me and Jasmine in one swoop.

‘I’m back, kids,’ he shouted, ‘and I won’t be going away again! I’ve got us a place to live just round the corner. We’re all going home at last.’

We squealed and shouted with happiness. I couldn’t believe Dad was back and we were leaving horrible Aunty Fatima’s.

We were full of questions, but Dad silenced us with a wave of the hand. ‘I know, I know, you want to ask everything,’ he said. ‘But first I want you to do something. There are some people outside I’d like you to meet. They’re in the car. Come on, I’ll show you.’

He took us by the hand and led us about 10 yards up the street to an old brown Datsun Sunny. A youngish shy-looking woman in a headscarf sat in the passenger seat, holding a baby. As we got up to the window she stared wide-eyed at us, then up at Dad. In the back of the car were three children who were jumping and scrabbling about like a family of monkeys. They seemed very keen to get out and yet they shrank back from the window as I leaned forward and looked in.

I turned to Dad. ‘Who are these people?’

‘This,’ he said slowly, ‘is your new mum. She’s come all the way from Pakistan to look after you. Isn’t that good?’

‘So why’s she brought these kids?’

‘They’re your brother and sisters. We’re going to live together. You’ve got some new kids to play with now, eh?’

Brother and sisters? I didn’t get it. Neither could I understand why we needed a new mum. I wanted to ask about the old one, but Dad seemed so happy to see us that I decided not to make him cross by mentioning her. Jasmine and I climbed onto the back seat of the Datsun, squeezing in next to the kids, who had suddenly become strangely silent.

‘This is Abida,’ Dad said, pointing at the woman in the front seat.

She smiled gently and said, ‘Hello there,’ in Pashto. I smiled back. She seemed nice – nicer than Fatima anyway.

‘And this is Rabida,’ Dad continued, gesturing to a girl of about 12. She ignored the introduction and looked out of the window at the row of terrace houses.

‘And these little ones are Baasima, Parvaiz and Nahid. Nahid’s the baby. Children, this is Mohammed and Jasmine. Say hello, everyone.’

The younger boy and girl, Parvaiz and Baasima, just stared at us. I shuffled around on the leatherette seat, not knowing what to do. The awkward moment was broken by Dad turning the key in the ignition and revving the engine as hard as he could before pulling away up the hill and out of Nile Street. I didn’t really care who these strangers were. We’d escaped from Fatima’s; for the moment, that was all that mattered.

The car turned into Hamilton Terrace, a street or two away from Fatima’s, and stopped outside a house in the middle of the row. From the outside, number 44 looked much the same as 97 Nile Street. The inside was depressingly familiar: two small rooms and a kitchen downstairs, two little bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs, plus a yard out the back. What was missing, thankfully, was Fatima’s sour face. I was very pleased about that and hardly noticed how shabby the house really was. From the beginning, despite Abida’s shyness, this felt like a happy home.

Dad started work as a jobbing builder and handyman, fixing drains, roof tiles, chimneys and window frames on houses all over Hawesmill. The condition of the properties meant work was plentiful. We were glad, not just because it brought some money in but also because Dad was around a lot more. His trips to Pakistan stopped and it slowly dawned on me that when Dad had introduced Rabida, Baasima, Parvaiz and Nahid as our ‘brother and sisters’ he had been telling us that he was their dad too. This was the family he’d left behind when he’d journeyed to England, the family that had patiently waited for him while he had married Mum and had us two.

Rabida was older than me. The others were younger. Dad had been a busy man on his trips abroad, that was obvious. I don’t know how Abida had reacted to the news of his English marriage. I expect she had taken the long-term view that one day she would come to England and take up her rightful place as Dad’s wife. I don’t know how she viewed Mum. Perhaps she thought she’d share Dad with her, as polygamy is not uncommon among Muslims. Or maybe she knew full well that Mum wouldn’t be around one day.

Dad tried his best to make this flung-together family work. When he had time off he’d take us all to a nearby park for an hour or two on the swings. It was lovely for us, because Fatima had never taken us anywhere. I can see him now, pushing me higher and higher until I could barely breathe with the thrill of it. The more I squealed, the more he laughed, the other kids pulling desperately at his trousers to make sure they got their turn. Once he piled us all into the back of the Datsun Sunny and took us to Blackpool for the day. It must have been my first visit to the seaside. I was overwhelmed by the experience. I sat at the water’s edge and dug in the sand, the sea filling up the hole as quickly as I could dig. The beach was packed with holidaymakers and daytrippers, all having fun. Above, seagulls wheeled and cried and I could almost taste the salty wind. It was one of the best days of my life so far and I didn’t want it to end.

The sleeping arrangements at Hamilton Terrace were almost as complicated as those at Nile Street, but at least Parvaiz didn’t wet the bed. Although there were a lot of us, the atmosphere around the house was nowhere near as frenetic as it had been at Fatima’s. Dad treated us all the same, as we were all his children. It was different with Abida: her own children came first every time. If they wanted an apple or a fig, they only had to ask. When Jasmine or I asked, the request was granted, but reluctantly. Now, I see that a mother naturally puts her own first, but back then I just felt that Abida was being difficult and sometimes unfair. At Eid, the holiday that marks the end of Ramadan, little gifts of money or sweets are given to children by adults grateful that the long period of fasting has finished. Abida’s four children always filled their pockets with bits and pieces given to them by their mum and dad. Sadly, Jasmine and I hardly ever shared in their good fortune. Dad, I suppose, was too busy to notice, but we certainly did.

That said, some months after we moved in I asked Abida if I could call her Ami, meaning ‘Mum’. She seemed very pleased that I thought of her in this way, and from then on I called her Mum at every available opportunity. It was nice to be able to say the word after so long, though it was tinged with sadness because it made me think of my real mum. The old image of the white face and dark hair would flash through my mind and I would desperately try to remember her features. But the memory had long gone.

Finally, I started primary school. I must have been around nine by then and had missed out on a huge amount in terms of reading and writing. There would be a lot of catching up to do, but I was prepared to put the work in.

The school was old-fashioned in terms of the building. The roof leaked in winter and when the boiler packed up in freezing conditions we were always sent home. The teachers were a kindly bunch. They were mainly elderly, female and white, and did their best to educate children who had been born in Britain but whose language and culture were based elsewhere. There weren’t many white faces among my classmates. Most white families had moved out of Hawesmill long before, not wanting to live next door to ‘Pakis’. Those who did stay put wanted little or nothing to do with us but refused to be ‘forced out’, as they saw it.

I found white people fascinating. We never went into the town and didn’t know any white people, so to be near them in the classroom was very interesting, even if they hardly spoke to me. I wished they would. I would hear Tamam’s taunts about the ‘white mother’ in my head, and wonder what life was like for these kids with white mums and dads. What did they talk about? Where did they go? What did they eat? My curiosity was stirred.

I made some progress at school and still attended the mosque school in Sebastopol Street as well. Abida did her best with us all at home, but she had been raised traditionally and wanted exactly the same for her children. Her girls were all shown how to cook, clean and keep house, and Jasmine was not immune from these chores. I remember coming downstairs one morning to find she’d been up for at least an hour washing the family’s clothes by hand in the sink. She was about seven at the time.

Dad seemed happy enough with the domestic arrangements. He breezed in and out of Hamilton Terrace, usually for meals, between labouring jobs. He loved his food, relishing the oily, traditional Pakistani curries made for him by Abida. He would mop up whatever remained with thick pieces of naan bread, licking his lips as he swallowed down the last of the rice.

‘Mum is a great cook,’ he’d say, as she cleared his plate away. ‘Best food I’ve ever had.’

Abida smiled, delighted that she was making her husband happy. After all, there is no greater honour for a Muslim wife than to serve her husband according to the laws of God.

After his meal, Dad would settle back on the settee in the back room, reading his paper and smoking heavily. I very rarely saw him without a cigarette in his mouth, and the house was thick with the smell of tobacco almost all the time, especially when his male friends came round for a chat and a game of cards, just as they would’ve done back in Tajak.