По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

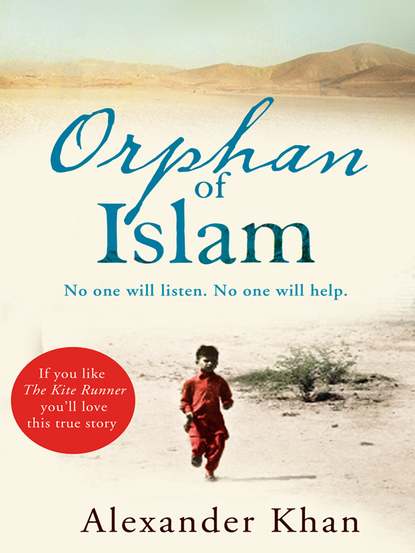

Orphan of Islam

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

One of these regular visitors was Rafiq, Abida’s brother. A skinny black-bearded man in his forties who always wore the traditional Pathan topi, or skullcap, he had left Pakistan some years previously to find work in England and had settled in Bradford with a much younger wife who had eventually walked out on him. They had had no children, so, perhaps out of shame or anger, he had left Bradford and come over the Pennines to Hawesmill. Because he was family, Dad took pity on him and welcomed him into the house. He stayed for a few nights before moving into a shared place around the corner and would come round frequently for food and company. He was a solitary brooding man with a deep voice who certainly wasn’t into entertaining us children. We seemed to irritate him hugely and I sensed that given the opportunity, he would lash out. Fortunately Dad was around almost every evening and so Rafiq had little chance to show off the temper I suspected was lurking under the surface.

Dad turned 50 in the early spring of 1985, just before I went into double figures myself. Friends and relations across the north of England were keen to see him, so one afternoon he told Jasmine and me to get our coats. We were going over to Blackburn to pick up a minibus, he explained. Then we’d come back to Hawesmill and collect Abida and the other kids, plus whoever else we could fit in, before heading off to relatives in Bradford. The Yorkshire city had a high number of Pathans living there, and those from the Attock district were either related to or friends of Dad. It would be a big get-together, with plenty of feasting and catching up.

We stood by the old Datsun, pulling impatiently at the passenger door handle. Never mind Bradford, a trip to Blackburn was a big deal, and we couldn’t wait to get going.

We waited and waited, and finally I went back into the house to hurry Dad up. I found him sitting in a chair in the front room, wiping his forehead with a handkerchief. Abida was fussing over him. Dad was naturally light-skinned, but he’d turned a weird sickly yellow colour.

I stood by his chair and pulled at his sleeve. ‘Come on, Dad, we want to go. Why are you sitting there? Come on, hurry up!’

He turned to me. There were dark rings under his eyes. He was sweating like mad. ‘I’m sorry, Moham,’ he said, ‘I’m not feeling so good. I don’t think I’m up to driving.’

I groaned out loud. I really wanted to go. I was sick of looking at the same four walls. I needed a change, even if it was only Blackburn and Bradford.

‘Come on, Dad,’ I pleaded. ‘You’ll be alright in a minute. We can always stop on the way. Please, Dad.’

He didn’t reply, just waved his hand in my direction. I sensed someone behind me and looked round. Rafiq was standing there, calmly taking in the scene.

‘I’ll go and get the minibus,’ he said. ‘I’ll get someone to drive your car back.’

‘Thanks, Rafiq,’ Dad said, taking a sip of water from a glass. Abida wiped his forehead again. ‘Would you mind taking the kids with you? They’re desperate for a trip out and I’ve promised them. Sorry, Rafiq. They’ll be good. Won’t you?’

I was torn between wanting a trip out and not wanting to go with Rafiq. I knew it would be an uncomfortable journey, but it would be a journey all the same.

‘Yes, Dad. I promise.’

‘Good lad. Go on then, off you go. I’ll be OK by the time you get back.’

I ran out and told Jasmine the news. She scrunched up her face when she heard who was taking us, but luckily she didn’t say anything, because within a second Rafiq was out of the front door, car keys in hand. He unlocked the car and indicated that we should get into the back. By trade he was a minicab driver, and we definitely felt like a couple of fares he’d just picked up. Jasmine started chatting straight away, but a look from Rafiq through the rear-view mirror was enough to shut her up and we drove to Blackburn in complete silence.

After 30 minutes or so we arrived at a house in the Whalley Range area of the town. This was the Hawesmill of Blackburn – steep hills, streets full of Asians and not a white face in sight. Like every other in the street, the house we were going to was a small brick-fronted terrace. A gang of kids playing outside peered into the car as we pulled up.

Rafiq let us out, telling us to stand by the car. He went into the house and came out five minutes later with a grey-bearded, grave-looking older man. This man pushed past us and opened the driver’s door. He wound down the window, said a quick few words to Rafiq and was gone.

‘Follow me,’ Rafiq said and we trotted up the hill behind him. Just before the brow of the hill we turned into a scruffy backstreet where a minibus was parked. Again we were consigned to the back seat. Again the journey took place in complete silence. The van smelled of diesel and I hoped I wouldn’t be sick. If I was, I knew for sure it wouldn’t be Rafiq cleaning it up.

I tried to concentrate on getting home and the journey to Bradford with Dad. We would laugh and joke with him as we crossed the Pennines, pointing out funny things by the road and playing ‘I spy’. He’d open the windows and get rid of this horrible fuel smell. Perhaps we’d stop at a café before we reached the city. Once Rafiq was out of the way we’d be fine.

As we reached Hawesmill and pulled into Hamilton Terrace there was a group of people standing outside number 44. Abida was in the middle of a group of women, and I could see Fatima, Ayesha and Yasir, Fatima’s eldest son, standing among them.

Rafiq pulled up against the kerb. ‘What’s going on?’ he shouted.

Yasir came over and leaned into the open window. He saw us and silently beckoned Rafiq out. Abida was clutching her hijab, or headscarf, across her face. She looked frightened. Someone put a hand on her shoulder and whispered to her. There was something terribly wrong.

The bus’s engine was still running as Abida and Rabida got in, along with Yasir. The younger children were hustled back into the house by Fatima. Rafiq climbed back into the driver’s seat.

‘Are we off to Bradford now?’ I said. ‘Why’s Dad not coming? Is he still poorly?’

Abida took hold of my hand. ‘He’s not very well, Mohammed,’ she said. ‘Not very well at all. He’s had to go to hospital. We’re going to see how he is.’

In the front seat Yasir turned round. ‘Don’t worry, kids,’ he said, smiling. ‘He’ll be OK. He’s just a bit … hurt. We’ll see him soon. That’ll cheer him up.’

We parked close by the hospital’s A and E department and hurried through its doors, the adults looking right and left down the wards to catch a glimpse of Dad. Everyone seemed to be staring at this scared-looking bunch of foreigners in their flowing clothes, running down corridors and shouting Dad’s name.

Ahead of us, a man in a white coat saw us coming and put out his hand to stop us in our tracks. ‘Can I help you?’ he said brightly. ‘Are you looking for anyone in particular?’

The women looked at one another. They knew no English and hadn’t a clue what the white man in the white coat had said. Rafiq knew a few words, but not enough to answer the doctor, and he simply shrugged his shoulders. Fortunately Yasir’s English was good, saving us from looking like a complete bunch of village idiots.

‘We’re looking for Ahmed Khan,’ he said, ‘from Hamilton Terrace, Hawesmill. He’s 50. He’s been brought in by ambulance. How is he? Can we see him?’

The doctor looked at his clipboard and ran his finger down a list of names. ‘Please, all of you come over here,’ he said, ‘just to the side of the ward.’

Obediently we shuffled into a small office off the main corridor.

The doctor bit his lip and looked down as he spoke. ‘I’m sorry to have to tell you that Mr Khan died half an hour ago. He had a huge heart attack.’

I caught the words but didn’t understand. Yasir paused, taking in the terrible news, then translated for Abida and the others. Immediately she started caterwauling, beating her chest and head with her shut fists. Rafiq stared out of the office door, expressionless, as Rabida wept and clung to her mother.

‘I’m sorry,’ repeated the doctor. ‘I’m afraid there was nothing we could do.’

The next hour or so was a blur of tears, screaming, shouting and grief-stricken fury. ‘Mr Khan died half an hour ago. Died … died … died …’ The doctor’s words were repeating in my head. Dad was dead. Something had happened to his heart and he’d died. We wouldn’t see him again. He’d gone, this time for good.

This couldn’t be happening. I’d never known anyone to die. It seemed a really stupid thing for Dad to do. Stupid enough for him to return home later on, when everyone had stopped crying, and apologize for being so daft. But he wasn’t going to. They said he was dead. Dead people didn’t come back.

Chapter Four

We arrived at Hamilton Terrace to find the house deserted. Rabida was sent down the street to Fatima’s with the bad news. Abida was still weeping and beating her chest. Rafiq and Yasir stood a few feet from her, not wishing to be contaminated by female grief. Muslim men have their own mourning rituals and there is little mutual comfort between the sexes, at least not in public. Jasmine and I stood on the pavement, not knowing where we belonged. Jasmine pulled at the sleeve of Abida’s jilbab, or coat, but she didn’t want to know. She was too caught up in the horrifying shock of what had happened.

Within five minutes Fatima came marching up the street, Rabida behind her, clutching the hands of the little kids we’d left in her care before we set off to the hospital. She was crying hard, but as the nearest of Dad’s relatives in this country, she was second in line to the chief mourner and therefore had work to do. The first job was to organize a very large pot of tea and find as many cups as possible.

The men, including Rafiq, Yasir and Dilawar, went into the front room and shut the door. The women trooped into the kitchen with us children. Chairs were arranged in a circle in the back room while Fatima made the tea. She put her arms around Abida and the two cried on each other’s shoulders, praying to God for Dad’s soul.

News of Dad’s death spread quickly and within quarter of an hour the little house was full of people from the surrounding streets. To us, all the women were ‘aunty’, no matter whether they were related or not. Many of these grieving ladies were gazing at Jasmine and me with pity as we stood bewildered in the back room.

‘God bless them,’ said one aunty, putting her hand on my head and pulling me to her. ‘What have they done to deserve this?’

She squeezed hard and I felt uncomfortable pressed up tight against her salwar kameez. As she released her grip, I was bundled into the folds of another mourner, who asked God to forgive us: ‘Astaghfirullah.’

‘Don’t worry, child,’ she whispered in my ear. ‘You will be fine. You will be looked after. God has willed it.’

In the far corner of the room Jasmine was getting an equal amount of attention. She was being passed from one aunty to another like a precious china doll. Our step-sisters and brother were around, and just as upset as we were, but getting nowhere near the amount of fuss.

‘Oh, Mohammed, God bless you, I’m so sorry about your father. He was a good man.’ A tubby aunty stood in front of me, her hand flat on the top of my head. She smiled sympathetically and wiped away a tear. ‘God bless you both,’ she said, ‘you poor little orphans.’

I stepped back, shocked. Orphans? How could we be? I’d heard the word in school, but had taken no notice of it. It seemed to be something that happened to people a hundred years ago. Then I realized: our Dad was dead and our Mum was … well, where was she? She certainly wasn’t here, and we hadn’t seen her for seven years. Did that mean she was dead too? Was it something they all knew about, but weren’t telling us?

Suddenly I felt very sick, and for the first time that day, my resistance crumbled and I began to cry. This had a chain reaction and soon the tiny back room was filled with women lifting their arms up to God and keening loudly with grief.

Not long after, the front-room door was opened and the men left the house. That room was also full to bursting and they’d decided to find a quieter place. Their way of mourning was to tell old stories about the deceased and make arrangements for the funeral. Under Islamic law the body must be washed, dressed in a shroud and buried as soon as possible, usually within hours of the death. As Dad’s body was to be flown back to Pakistan, however, this wasn’t possible. His funeral would be in two days, followed by immediate repatriation. In Muslim communities, individuals pay into a fund that covers funeral and travel expenses. One family looks after this money and makes all the arrangements when a person dies. The men were obviously going away to discuss this.