По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

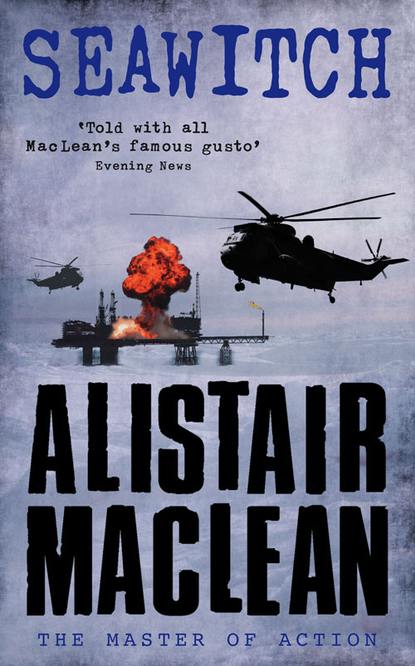

Seawitch

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘“Might,” I said. For us, the element of risk does not exist.’

‘May we see this man?’

Benson nodded, rose, went to a door and admitted Cronkite.

Cronkite was a Texan. In height, build and cragginess of features he bore a remarkable resemblance to John Wayne. Unlike Wayne he never smiled. His face was of a peculiarly yellow complexion, typical of those who have had an overdose of anti-malarial tablets, which was just what had happened to Cronkite. Mepacrine does not make for a peaches and cream complexion – not that Cronkite had ever had anything even remotely resembling that. He was newly returned from Indonesia, where he had inevitably maintained his hundred percent record.

‘Mr Cronkite,’ Benson said. ‘Mr Cronkite, this is –’

Cronkite was brusque. In a gravelly voice he said: ‘I do not wish to know their names.’

In spite of the abruptness of his tone, several of the oilmen round the table almost beamed. Here was a man of discretion, a man after their own hearts.

Cronkite went on: ‘All I understand from Mr Benson is that I am required to attend to a matter involving Lord Worth and the Seawitch. Mr Benson has given me a pretty full briefing. I know the background. I would like, first of all, to hear any suggestions you gentlemen may have to offer.’ Cronkite sat down, lit what proved to be a very foul-smelling cigar, and waited expectantly.

He kept silent during the following half-hour discussion. For ten of the world’s top businessmen they proved to be an extraordinary inept, not to say inane lot. They talked in an ever-narrowing series of concentric circles.

Henderson said: ‘First of all it must be agreed that there is no violence to be used. Is it so agreed?’

Everybody nodded their agreement. Each and every one of them was a pillar of business respectability who could not afford to have his reputation besmirched in any way. No one appeared to notice that Cronkite sat motionless as a graven image. Except for lifting a hand to puff out increasingly vile clouds of smoke, Cronkite did not move throughout the discussion. He also remained totally silent.

After agreeing that there should be no violence the meeting of ten agreed on nothing.

Finally Patinos spoke up. ‘Why don’t you – one of you four Americans, I mean – approach your Congress to pass an emergency law banning offshore drilling in extra-territorial waters?’

Benson looked at him with something akin to pity. ‘I am afraid, sir, that you do not quite understand the relations between the American majors and Congress On the few occasions we have met with them – something to do with too much profits and too little tax – I’m afraid we have treated them in so – ah – cavalier a fashion that nothing would give than greater pleasure than to refuse any request we might make.’

One of the others, known simply as ‘Mr A’, said: ‘How about an approach to that international legal ombudsman, the Hague? After all, this is an international matter.’

‘Not on.’ Henderson shook his head ‘Forget it. The dilatoriness of that august body is so legendary that all present would be long retired – or worse – before a decision is made. The decision would just as likely be negative anyway.’

‘UNO?’ Mr A said.

‘That talk-shop!’ Benson had obviously a low and not uncommon view of the UNO. ‘They haven’t even the power to order New York to install a new parking meter outside their front door.’

The next revolutionary idea came from one of the Americans.

‘Why shouldn’t we all agree, for an unspecified time – let’s see how it goes – to lower our price below that of Worth Hudson. In that case no one would want to buy their oil.’

This proposal was met with a stunned disbelief.

Corral spoke in a kind voice. ‘Not only would that lead to vast losses to the major oil companies, but would almost certainly and immediately lead Lord Worth to lower his prices fractionally below their new ones. The man has sufficient working capital to keep him going for a hundred years at a loss – in the unlikely event, that is, of his running at a loss at all.’

A lengthy silence followed. Cronkite was not quite as immobile as he had been. The granitic expression on his face remained unchanged but the fingers of his non-smoking hand had begun to drum gently on the arm-rest of his chair. For Cronkite, this was equivalent to throwing a fit of hysterics.

It was during this period that all thoughts of the ten of maintaining their high, gentlemanly and ethical standards against drilling in international waters were forgotten.

‘Why not,’ Mr A said, ‘buy him out?’ In fairness to Mr A it has to be said that he did not appreciate just how wealthy Lord Worth was and that, immensely wealthy though he, Mr A, was, Lord Worth could have bought him out lock, stock and barrel. ‘The Seawitch rights, I mean. A hundred million dollars. Let’s be generous, two hundred million dollars. Why not?’

Corral looked depressed. ‘The answer “why not” is easy. By the latest reckoning Lord Worth is one of the world’s five richest men and even two hundred million dollars would only come into the category of pennies as far as he was concerned.’

Mr A looked depressed.

Benson said: ‘Sure, he’d sell.’

Mr A visibly brightened.

‘For two reasons only. In the first place he’d make a quick and splendid profit. In the second place, for less than half the selling price, he could build another Seawitch, anchor it a couple of miles away from the present Seawitch – there are no leasehold rights in extra-territorial waters – and start sending oil ashore at his same old price.’

A temporarily deflated Mr A slumped back in his armchair.

‘A partnership, then,’ Mr A said. His tone was that of a man in a state of quiet despair.

‘Out of the question.’ Henderson was very positive. ‘Like all very rich men, Lord Worth is a born loner. He wouldn’t have a combined partnership with the King of Saudi Arabia and the Shah of Persia even if it had been offered him.’

In a pall-like gloom a baffled and exhausted silence fell upon the embattled ten. A thoroughly bored and hitherto wordless John Cronkite rose.

He said without preamble: ‘My personal fee will be one million dollars. I will require ten million dollars for operating expenses. Every cent of this will be accounted for and the unspent balance returned. I demand a completely free hand and no interference from any of you. If I do encounter any such interference I shall retain the balance of the expenses and at the same time abandon the mission. I refuse to disclose what my plans are – or will be when I have formulated them. Finally, I would prefer to have no further contact with any of you, now or at any time.’

The certainty and confidence of the man were astonishing. Agreement among the mightily-relieved ten was immediate and total. The ten million dollars – a trifling sum to those accustomed to spending as much in bribes every month or so – would be delivered within twenty-four, at the most forty-eight hours to a Cuban numbered account in Miami – the only place in the United States where Swiss-type numbered accounts were permitted. For tax evasion purposes the money, of course, would not come from any of their respective countries; instead, ironically enough, from their bulging offshore funds.

Chapter Two (#ulink_8ed927aa-4753-52d5-9556-a6eacbf9dc9f)

Lord Worth was tall, lean and erect. His complexion was of the mahogany hue of the playboy millionaire who spends his life in the sun: Lord Worth seldom worked less than sixteen hours a day. His abundant hair and moustache were snow-white. According to his mood and expression and to the eye of the beholder he could have been a Biblical patriarch, a better-class Roman senator or a gentlemanly seventeenth-century pirate – except for the fact, of course, that none of those ever, far less habitually, wore lightweight alpaca suits of the same colour as Lord Worth’s hair.

He looked and was every inch an aristocrat. Unlike the many Americanas who bore the Christian names of Duke or Earl, Lord Worth really was a lord, the fifteenth in succession of a highly distinguished family of Scottish peers of the realm. The fact that their distinction had lain mainly in the fields of assassination, endless clan warfare, the stealing of women and cattle and the selling of their fellow peers down the river was beside the point: the earlier Scottish peers didn’t go in too much for the more cultural activities. The blue blood that had run in their veins ran in Lord Worth’s. As ruthless, predatory, acquisitive and courageous as any of his ancestors, Lord Worth simply went about his business with a degree of refinement and sophistication that would have lain several light years beyond their understanding.

He had reversed the trend of Canadians coming to Britain, making their fortunes and eventually being elevated to the peerage: he had already been a peer, and an extremely wealthy one, before emigrating to Canada. His emigration, which had been discreet and precipitous, had not been entirely voluntary. He had made a fortune in real estate in London before the Internal Revenue had become embarrassingly interested in his activities. Fortunately for him, whatever charges which might have been laid against his door were not extraditable.

He had spent several years in Canada, investing his millions in the Worth Hudson Oil Company and proving himself to be even more able in the oil business than he had been in real estate. His tankers and refineries spanned the globe before he had decided that the climate was too cold for him and moved south to Florida. His splendid mansion was the envy of the many millionaires – of a lesser financial breed, admittedly – who almost literally jostled for elbow-room in the Fort Lauderdale area.

The dining-room in that mansion was something to behold. Monks, by the very nature of their calling, are supposed to be devoid of all earthly lusts, but no monk, past or present, could ever have gazed on the gleaming magnificence of that splendid oaken refectory table without turning pale chartreuse in envy. The chairs, inevitably, were Louis XIV. The splendidly embroidered silken carpet, with a pile deep enough for a fair-sized mouse to take cover in, would have been judged by an expert to come from Damascus and to have cost a fortune: the expert would have been right on both counts. The heavy drapes and embroidered silken walls were of the same pale grey, the latter being enhanced by a series of original Impressionist paintings, no less than three by Matisse and the same number by Renoir. Lord Worth was no dilettante and was clearly trying to make amends for his ancestors’ shortcomings in the cultural fields.

It was in those suitably princely surroundings that Lord Worth was at the moment taking his ease, revelling in his second brandy and the company of the two beings whom after money – he loved most in the world: his two daughters Marina and Melinda, who had been so named by their now divorced Spanish mother. Both were young, both were beautiful, and could have been mistaken for twins, which they weren’t: they were easily distinguishable by the fact that while Marina’s hair was black as a raven’s wing Melinda’s was pure titian.

There were two other guests at the table. Many a local millionaire would have given a fair slice of his ill-gotten gains for the privilege and honour of sitting at Lord Worth’s table. Few were invited, and then but seldom. These two young men, comparatively as poor as church mice, had the unique privilege, without invitation, of coming and going as they pleased, which was pretty often.

Mitchell and Roomer were two pleasant men in their early thirties for whom Lord Worth had a strong if concealed admiration and whom he held in something close to awe – inasmuch as they were the only two completely honest men he had ever met. Not that Lord Worth had ever stepped on the wrong side of the law, although he frequently had a clear view of what happened on the other side: it was simply that he was not in the habit of dealing with honest men. They had both been highly efficient police sergeants, only they had been too efficient, much given to arresting the wrong people such as crooked politicians and equally crooked wealthy businessmen who had previously laboured under the misapprehension that they were above the law. They were fired, not to put too fine a point on it, for their total incorruptibility.

Of the two Michael Mitchell was the taller, the broader and the less good-looking. With slightly craggy face, ruffled dark hair and blue chin, he could never have made it as a matinée idol. John Roomer, with his brown hair and trimmed brown moustache, was altogether better-looking. Both were shrewd, intelligent and highly experienced. Roomer was the intuitive one, Mitchell the one long on action. Apart from being charming both men were astute and highly resourceful. And they were possessed of one other not inconsiderable quality: both were deadly marksmen.

Two years previously they had set up their own private investigative practice, and in that brief space of time had established such a reputation that people in real trouble now made a practice of going to them instead of to the police, a fact that hardly endeared them to the local law. Their homes and combined office were within two miles of Lord Worth’s estate where, as said, they were frequent and welcome visitors. That they did not come for the exclusive pleasure of his company Lord Worth was well aware. Nor, he knew, were they even in the slightest way interested in his money, a fact that Lord Worth found astonishing, as he had never previously encountered anyone who wasn’t thus interested. What they were interested in, and deeply so, were Marina and Melinda.

The door opened and Lord Worth’s butler, Jenkins – English, of course, as were the two footmen – made his usual soundless entrance, approached the head of the table and murmured discreetly in Lord Worth’s ear. Lord Worth nodded and rose.

‘Excuse me, girls, gentlemen. Visitors. I’m sure you can get along together quite well without me.’ He made his way to his study, entered and closed the door behind him, a very special padded door that, when shut, rendered the room completely soundproof.

The study, in its own way – Lord Worth was no sybarite but he liked his creature comforts as well as the next man – was as sumptuous as the dining-room: oak, leather, a wholly unnecessary log fire burning in one corner, all straight from the best English baronial mansions. The walls were lined with thousands of books, many of which Lord Worth had actually read, a fact that must have caused great distress to his illiterate ancestors, who had despised degeneracy above all else.