По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

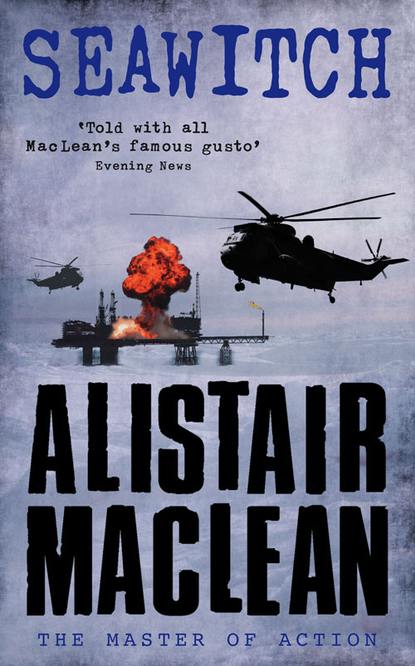

Seawitch

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A tall bronzed man with aquiline features and grey hair rose to his feet. Both men smiled and shook hands warmly.

Lord Worth said: ‘Corral, my dear chap! How very nice to see you again. It’s been quite some time.’

‘My pleasure, Lord Worth. Nothing recently that would have interested you.’

‘But now?’

‘Now is something else again.’

The Corral who stood before Lord Worth was indeed the Corral who, in his capacity as representative of the Florida off-shore leases, had been present at the meeting of ten at Lake Tahoe. Some years had passed since he and Lord Worth had arrived at an amicable and mutually satisfactory agreement. Corral, widely regarded as Lord Worth’s most avowedly determined enemy and certainly the most vociferous of his critics, reported regularly to Lord Worth on the current activities and, more importantly, the projected plans of the major companies, which didn’t hurt Lord Worth at all. Corral, in return, received an annual tax-free retainer of $200,000, which didn’t hurt him very much either.

Lord Worth pressed a bell and within seconds Jenkins entered bearing a silver tray with two large brandies. There was no telepathy involved, just years of experience and a long-established foreknowledge of Lord Worth’s desires. When he left both men sat.

Lord Worth said: ‘Well, what news from the west?’

‘The Cherokee, I regret to say, are after you.’

Lord Worth sighed and said: ‘It had to come some time. Tell me all.’

Corral told him all. He had a near-photographic memory and a gift for concise and accurate reportage. Within five minutes Lord Worth knew all that was worth knowing about the Lake Tahoe meeting.

Lord Worth who, because of the unfortunate misunderstanding that had arisen between himself and Cronkite, knew the latter as well as any and better than most, said at the end of Corral’s report: ‘Did Cronkite subscribe to the ten’s agreement to abjure any form of violence?’

‘No.’

‘Not that it would have mattered if he had. Man’s a total stranger to the truth. And ten million dollars expenses, you tell me?’

‘It did seem a bit excessive.’

‘Can you see a massive outlay like that being concommitant with anything except violence?’

‘No.’

‘Do you think the others believed that there was no connection between them?’

‘Let me put it this way, sir. Any group of people who can convince themselves, or appear to convince themselves, that any action proposed to be taken against you is for the betterment of mankind is also prepared to convince themselves, or appear to convince themselves, that the word “Cronkite” is synonymous with peace on earth.’

‘So their consciences are clear. If Cronkite goes to any excessive lengths in death and destruction to achieve their ends they can always throw up their hands in horror and say, “Good God, we never thought the man would go that far.” Not that any connection between them and Cronkite would ever be established. What a bunch of devious, mealy-mouthed hypocrites!’

He paused for a moment.

‘I suppose Cronkite refused to divulge his plans?’

‘Absolutely. But there is one little and odd circumstance that I’ve kept for the end. Just as we were leaving Cronkite drew two of the ten to one side and spoke to them privately. It would be interesting to know why.’

‘Any chance of finding out?’

‘A fair chance. Nothing guaranteed. But I’m sure Benson could find out – after all, it was Benson who invited us all to Lake Tahoe.’

‘And you think you could persuade Benson to tell you?’

‘A fair chance. Nothing more.’

Lord Worth put on his resigned expression. ‘All right, how much?’

‘Nothing. Money won’t buy Benson.’ Corral shook his head in disbelief. ‘Extraordinary, in this day and age, but Benson is not a mercenary man. But he does owe me the odd favour, one of them being that, without me, he wouldn’t be the president of the oil company that he is now.’ Corral paused. ‘I’m surprised you haven’t asked me the identities of the two men Cronkite took aside.’

‘So am I.’

‘Borosoff of the Soviet Union and Pantos of Venezuela.’ Lord Worth appeared to lapse into a trance. ‘That mean anything to you?’

Lord Worth bestirred himself. ‘Yes. Units of the Russian navy are making a so-called “goodwill tour” of the Caribbean. They are, inevitably, based on Cuba. Of the ten, those are the only two that could bring swift – ah – naval intervention to bear against the Seawitch.’ He shook his head. ‘Diabolical. Utterly diabolical.’

‘My way of thinking too, sir. There’s no knowing. But I’ll check as soon as possible and hope to get results.’

‘And I shall take immediate precautions.’ Both men rose. ‘Corral, we shall have to give serious consideration to the question of increasing this paltry retainer of yours.’

‘We try to be of service, Lord Worth.’

Lord Worth’s private radio room bore more than a passing resemblance to the flight deck of his private 707. The variety of knobs, switches, buttons and dials was bewildering. Lord Worth seemed perfectly at home with them all, and proceeded to make a number of calls.

The first of these were to his four helicopter pilots, instructing them to have his two largest helicopters – never a man to do things by halves, Lord Worth owned no fewer than six of these machines – ready at his own private airfield shortly before dawn. The next four were to people of whose existence his fellow directors were totally unaware. The first was to Cuba, the second to Venezuela. Lord Worth’s world-wide range of contacts – employees, rather – was vast. The instructions to both were simple and explicit. A constant monitoring watch was to be kept on the naval bases in both countries, and any sudden and expected departures of any naval vessels, and their type, was to be reported to him immediately.

The third, to a person who lived not too many miles away, was addressed to a certain Giuseppe Palermo, whose name sounded as if he might be a member of the Mafia, but who definitely wasn’t: the Mafia Palermo despised as a mollycoddling organization which had become so ludicrously gentle in its methods of persuasion as to be in imminent danger of becoming respectable. The next call was to Baton Rouge in Louisiana, where there lived a person who only called himself ‘Conde’ and whose main claim to fame lay in the fact that he was the highest-ranking naval officer to have been court-martialled and dishonourably discharged since World War Two. He, like the others, received very explicit instructions. Not only was Lord Worth a master organizer, but the efficiency he displayed was matched only by his speed in operation.

The noble lord, who would have stoutly maintained – if anyone had the temerity to accuse him, which no one ever had – that he was no criminal, was about to become just that. Even this he would have strongly denied and that on three grounds. The Constitution upheld the rights of every citizen to bear arms; every man had the right to defend himself and his property against criminal attack by whatever means lay to hand; and the only way to fight fire was with fire.

The final call Lord Worth put through, and this time with total confidence, was to his tried and trusted lieutenant, Commander Larsen.

Commander Larsen was the captain of the Seawitch.

Larsen – no one knew why he called himself ‘Commander’, and he wasn’t the kind of person you asked – was a rather different breed of man from his employer. Except in a public court or in the presence of a law officer he would cheerfully admit to anyone that he was both a non-gentleman and a criminal. And he certainly bore no resemblance to any aristocrat, alive or dead. But for all that there did exist a genuine rapport and mutual respect between Lord Worth and himself. In all likelihood they were simply brothers under the skin.

As a criminal and non-aristocrat – and casting no aspersions on honest unfortunates who may resemble him – he certainly looked the part. He had the general build and appearance of the more viciously daunting heavy-weight wrestler, deep-set black eyes that peered out under the overhanging foliage of hugely bushy eyebrows, an equally bushy black beard, a hooked nose and a face that looked as if it had been in regular contact with a series of heavy objects. No one, with the possible exception of Lord Worth, knew who he was, what he had been or from where he had come. His voice, when he spoke, came as a positive shock: beneath that Neanderthaloid façade was the voice and the mind of an educated man. It really ought not to have come as such a shock: beneath the façade of many an exquisite fop lies the mind of a retarded fourth-grader.

Larsen was in the radio room at that moment, listening attentively, nodding from time to time, then flicked a switch that put the incoming call on to the loudspeaker.

He said: ‘All clear, sir. Everything understood. We’ll make the preparations. But haven’t you overlooked something, sir?’

‘Overlooked what?’ Lord Worth’s voice over the telephone carried the overtones of a man who couldn’t possibly have overlooked anything.

‘You’ve suggested that armed surface vessels may be used against us. If they’re prepared to go to such lengths isn’t it feasible that they’ll go to any lengths?’

‘Get to the point, man.’

‘The point is that it’s easy enough to keep an eye on a couple of naval bases. But I suggest it’s a bit more difficult to keep an eye on a dozen, maybe two dozen airfields.’

‘Good God!’ There was a long pause during which the rattle of cogs and the meshing of gear-wheels in Lord Worth’s brain couldn’t be heard. ‘Do you really think –’