По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

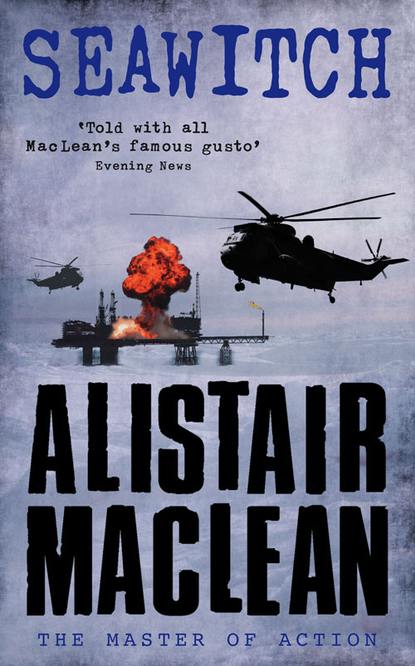

Seawitch

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘If I were on the Seawitch, Lord Worth, it would be six and half a dozen to me whether I was clobbered by shells or bombs. And planes could get away from the scene of the crime a damn sight faster than ships. They could get clean away. The US navy or land-based bombers would have a good chance of intercepting surface vessels. And another thing, Lord Worth.’

There was a moment’s pause.

‘A ship could stop at a distance of a hundred miles. No distance at all for the guided missile, I believe they have a range of four thousand miles these days. When the missile was, say, twenty miles from us, they could switch on its heat-source tracking device. God knows, we’re the only heat-source for a hundred miles around.’

Another lengthy pause, then: ‘Any more encouraging thoughts occur to you, Commander Larsen?’

‘Yes, sir. Just one. If I were the enemy – I may call them the enemy –’

‘Call the devils what you want.’

‘If I were the enemy I’d use a submarine. They don’t even have to break water to loose off a missile. Poof! No Seawitch. No signs of any attacker. Could well be put down to a massive explosion aboard the Seawitch. Far from impossible, sir.’

‘You’ll be telling me next that there’ll be atomic-headed missiles.’

‘To be picked up by a dozen seismological stations? I should think it hardly likely, sir. But that may just be wishful thinking. I have no wish to be vaporized.’

‘I’ll see you in the morning.’ The line went dead.

Larsen hung up his phone and smiled widely. One would have subconsciously imagined this action to reveal a set of yellowed fangs: instead, it revealed a perfect set of gleamingly white teeth. He turned to look at Scoffield, his head driller and right-hand man.

Scoffield was a large, rubicund, smiling man, the easy-going essence of good nature. To the fact that this was not precisely the case any member of his drilling crews would have eagerly and blasphemously testified. Scoffield was a very tough citizen indeed and one could assume that it was not innate modesty that made him conceal this: much more probably it was a permanent stricture of the facial muscles caused by the four long vertical scars on his cheeks, two on either side. Clearly he, like Larsen, was no great advocate of plastic surgery. He looked at Larsen with understandable curiosity.

‘What was all that about?’

‘The day of reckoning is at hand. Prepare to meet thy doom. More specifically, his lordship is beset by enemies.’ Larsen outlined Lord Worth’s plight. ‘He’s sending what sounds like a battalion of hard men out here in the early morning, accompanied by suitable weaponry. Then in the afternoon we are to expect a boat of some sort, loaded with even heavier weaponry.’

‘One wonders where he’s getting all those hard men and weaponry from.’

‘One wonders. One does not ask.’

‘All this talk – your talk – about bombers and submarines and missiles. Do you believe that?’

‘No. It’s just that it’s hard to pass up the opportunity to ruffle the aristocratic plumage.’ He paused then said thoughtfully: ‘At least I hope I don’t believe it. Come, let us examine our defences.’

‘You’ve got a pistol. I’ve got a pistol. That’s defences?’

‘Well, where we’ll mount the defences when they arrive. Fixed large-bore guns, I should imagine.’

‘If they arrive.’

‘Give the devil his due. Lord Worth delivers.’

‘From his own private armoury, I suppose.’

‘It wouldn’t surprise me.’

‘What do you really think, Commander?’

‘I don’t know. All I know is that if Lord Worth is even half-way right life aboard may become slightly less monotonous in the next few days.’

The two men moved out into the gathering dusk on to the platform. The Seawitch was moored in 150 fathoms of water – 900 feet – which was well within the tensioning cables’ capacities – safely south of the US’s mineral leasing blocks and the great east-west fairway, straight on top of the biggest oil reservoir yet discovered round the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. The two men paused at the drilling derrick where a drill, at its maximum angled capacity, was trying to determine the extent of the oilfield. The crew looked at them without any particular affection but not with hostility. There was reason for the lack of warmth.

Before any laws were passed making such drilling illegal, Lord Worth wanted to scrape the bottom of this gigantic barrel of oil. Not that he was particularly worried, for government agencies are notoriously slow to act: but there was always the possibility that they might bestir themselves this time and that, horror of horrors, the bonanza might turn out to be vastly larger than estimated.

Hence the present attempt to discover the limits of the strike and hence the lack of warmth. Hence the reason why Larsen and Scoffield, both highly gifted slave-drivers, born centuries out of their time, drove their men day and night. The men disliked it, but not to the point of rebellion. They were highly paid, well housed and well fed. True, there was little enough in the way of wine, women and song but then, after an exhausting twelve-hour shift, those frivolities couldn’t hope to compete with the attractions of a massive meal then a long, deep sleep. More importantly and most unusually, the men were paid a bonus on every thousand barrels of oil.

Larsen and Scoffield made their way to the western apex of the platform and gazed out at the massive bulk of the storage tank, its topsides festooned with warning lights. They gazed at this for some time, than turned and walked back towards the accommodation quarters.

Scoffield said: ‘Decided upon your gun emplacements yet, Commander – if there are any guns?’

‘There’ll be guns.’ Larsen was confident. ‘But we won’t need any in this quarter.’

‘Why?’

‘Work it out for yourself. As for the rest, I’m not too sure. It’ll come to me in my sleep. My turn for an early night. See you at four.’

The oil was not stored aboard the rig – it is forbidden by a law based strictly on common sense to store hydrocarbons at or near the working platform of an oil rig. Instead, Lord Worth, on Larsen’s instructions – which had prudently come in the form of suggestions – had had built a huge floating tank which was anchored, on a basis exactly similar to that of the Seawitch herself, at a distance of about three hundred yards. Cleansed oil was pumped into this after it came up from the ocean floor, or, more precisely, from a massive limestone reef deep down below the ocean floor, a reef caused by tiny marine creatures of a now long-covered shallow sea of anything up to half a billion years ago.

Once, sometimes twice a day, a 50,000 dw tanker would stop by and empty the huge tank. There were three of those tankers employed on the criss-cross run to the southern US. The Worth Hudson Oil Company did, in fact, have supertankers, but the use of them in this case did not serve Lord Worth’s purpose. Even the entire contents of the Seawitch tank would not have filled a quarter of the super-tanker’s carrying capacity, and the possibility of a super-tanker running at a loss, however small, would have been the source of waking nightmares for the Worth Hudson: equally important, the more isolated ports which Lord Worth favoured for the delivery of his oil were unable to offer deep-water berth-side facilities for anything in excess of 50,000 dw.

It might in passing be explained that Lord Worth’s choice of those obscure ports was not entirely fortuitous. Among those who were a party to the gentlemen’s agreement against offshore drilling – some of the most vociferous of those who roundly condemned Worth Hudson’s nefarious practices – were regrettably Worth Hudson’s best customers. They were the smaller companies who operated on marginal profits and lacked the resources to engage in research and exploration, which the larger companies did, investing allegedly vast sums in those projects and then, to the continuous fury of the Internal Revenue Service and the anger of numerous Congressional investigation committees, claiming even vaster tax exemptions.

But to the smaller companies the lure of cheaper oil was irresistible. The Seawitch, which probably produced as much oil as all the government official leasing areas combined, seemed a sure and perpetual source of cheap oil until, that was, the government stepped in, which might or might not happen in the next decade: the big companies had already demonstrated their capacity to deal with inept Congressional enquiries and, as long as the energy crisis continued, nobody was going to worry very much about where oil came from, as long as it was there. In addition, the smaller companies felt, if the OPEC – the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries – could play ducks and drakes with oil prices whenever they felt like it, why couldn’t they?

Less than two miles from Lord Worth’s estate were the adjacent homes and common office of Michael Mitchell and John Roomer. It was Mitchell who answered the door bell.

The visitor was of medium height, slightly tubby, wore wire-rimmed glasses and alopecia had hit him hard. He said: ‘May I come in?’ in a clipped but courteous enough voice.

‘Sure.’ Mitchell let him in. ‘We don’t usually see people this late.’

‘Thank you. I come on unusual business. James Bentley.’ A little sleight of hand and a card appeared. ‘FBI.’

Mitchell didn’t even look at it. ‘You can have those things made at any joke shop. Where you from?’

‘Miami.’

‘Phone number?’

Bentley reversed the card which Mitchell handed to Roomer. ‘My memory man. Saves me from having to have a memory of my own.’

Roomer didn’t glance at the card either. ‘It’s okay, Mike. I have him. You’re the boss man up there, aren’t you?’ A nod. ‘Please sit down, Mr Bentley.’

‘One thing clear, first,’ Mitchell said. ‘Are we under investigation?’

‘On the contrary. The State Department has asked me to ask you to help them.’

‘Status at last,’ Mitchell said. ‘We’ve got it made, John, but for one thing – the State Department don’t know who the hell we are.’