По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

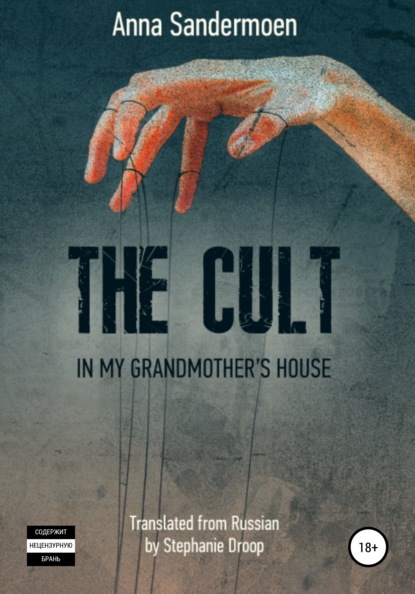

The Cult in my Grandmother's House

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Cult in my Grandmother's House

Анна Сандермоен

When eight-year-old Ania is sent to stay with her grandmother for the summer holidays, she finds a house full of strangers and a grandmother who pretends not to know her. Ania only returns home six years later. This autobiography is about childhood in an illegal cult in the USSR, involving the scientific and creative elite of the Soviet Union. The cult's leader, V. D. Stolbun, claimed to be raising a breed of superhuman immune to any physical or mental illness. Any totalitarian cult is built on a strict hierarchy and is controlled entirely by its leader, whose only motive is power. This is a book about adults betraying the children in their care. It warns us to be wary of anyone who claims to be "saving the world", and contains tools to identify a cult before it is too late. The author managed to free herself from the puppetmaster's grip, but his appalling activities continue to this day. Содержит нецензурную брань.

Анна Сандермоен

The Cult in my Grandmother's House

ANNA SANDERMOEN

THE CULT

IN MY GRANDMOTHER’S HOUSE

Translated from Russian

by Stephanie Droop

Introduction by Kjetil Sandermoen

The story you are about to read was written by my dear wife Ania. It is a true story about a large part of her childhood, and I am sure it will move and impact you.

Among a lot of incredibly shocking anecdotes in this book, the one that touched me the most is where Ania describes how she was sent back to her grandmother’s house, so full of happy and joyful memories, only to find it full of strangers living there in what turned out to be a cult, and her loving grandmother now treating the young girl as if she was an unwanted stranger. That Ania has chosen to call her book The Cult in my Grandmother’s House is probably evidence that this particular part of her story affected her deeply as well.

When I met my wife and she eventually told me just a little bit about her background of growing up in a cult, I must admit I had to discuss with myself how this could have given rise to fears and problems that she would bring with her into our relationship.

Ania is a very strong and proud person and it is not her habit to focus on the negative aspects of life. The childhood stories that she usually shares with friends and family are the fun and nostalgic ones. However, I know that the years taken from her childhood spent in a cult is a painful past that she will always bring with her. I have therefore encouraged her to write this book about these years. It can stand as a warning to any adult who would contemplate joining a cult or a sect, or – as in Ania case even worse – sending your child away to a cult. I believe that writing the book is also a part of a healing process for Ania. It is a story worth writing down and indeed a story worth reading.

Any kind of cult is dangerous and destructive. The core of a cult is sectarianism, which is the idea that members of the cult are convinced that their salvation and success, based on their particular objectives, aggressively require to find converts from outside the cult in order to succeed with their political, religious or ideological project. It is always based on a very oppressive hierarchy, almost always under the dictatorial leadership of a charlatan whose motives are dominance, power, and sexual and material privileges.

The cult that Ania describes in this book is in my opinion extraordinarily dangerous since it claims it can cure disorders like schizophrenia and fatal diseases like cancer. The idea was that children are spoiled and become “weak” by being brought up by their parents and therefore have to be taken care of by strangers. Illness is (according to this cult) a result of negative thinking by weak humans. The leader claimed that the whole world was suffering from schizophrenia (he made a big market for himself). Only his wisdom could cure it.

These ideas were unfortunately in unison with the prevailing ideology of the USSR where they wanted to diminish the family and replace it with upbringing by the Communist Party to create the Homo sovieticus. In the USSR people were also readily accused of being schizophrenic and sent away for forced “treatment” if they had the courage to stand up against this totalitarian system.

I have observed that still today any mental disorder is nonchalantly labelled “schizophrenia” in Russia. It is as if it is not completely understood that this is a very serious, disabling and incurable psychiatric disorder. Schizophrenia involves a number of serious problems with thinking, behaviour or emotions and it requires lifelong medication and treatment. I am absolutely confident that very few – if any – members of this cult were actually suffering from schizophrenia. However, they were manipulated into obedience and treated with ridiculous methods by dilettantes.

As I understand it, this cult still exists and practices its unauthorised “treatment” in the middle of Moscow.

The worst emotional pain a child can experience is to feel abandoned by her parents. Children do not have a choice. A child cannot choose her parents and she cannot choose what is done to her. However, even when let down and treated unfairly, children are equipped with an incredible ability to love their parents. I know that Ania does not feel any hate towards her parents or anyone else. It is not up to me to cast judgments about what Ania parents did to her. The times and the conditions in the USSR were so completely different from anything I myself grew up with, that I can hardly comprehend it. I do believe however, that Ania feels disappointment and an emptiness in her heart where the love for her parents should have been. I do my best to help Ania in finding a perspective in this regard. The best healer however would have been just an honest, “I am sorry for what happened, we did wrong to you”. That would have meant a lot for Ania.

Read, reflect and learn from this excellently written book.

Kjetil Sandermoen,

September 03, 2019

Zug, Switzerland

Foreword

Under tyranny it is much easier to act than to think.

Hannah Arendt, philosopher

WHO AM I?

I am a capricious, selfish, critical and permanently dissatisfied little bitch. I’m a materialistic, opportunistic animal, always calculating a few steps ahead. I’m a bourgeoise. At least, this is what I was assured of right from childhood, extensively and persistently, and, I must admit, very successfully.

But once, to my great surprise, my husband told me he liked the fact that I wasn’t some spoilt little European thing, but a steely Russian with a good (albeit a little strange) sense of humour.

I was 39 years old when he proposed to me, and I thought it would be dishonest on my part to unite my life with a person without telling him about my past, about my childhood. I wouldn’t be able to keep silent about this all my life, and if I told him it in snatches, then he might have formed an incomplete or even wrong impression of me. That might have been fine if he was Russian – Russians aren’t fazed by most far-out stories. But he is Norwegian, and he was raised in a decent family, in the sort of abundance I never dreamed of, and, most importantly, surrounded by love and care. A decent environment gave him moral guidance; wealth fostered his severe self-discipline; and love and care made his heart responsive. Therefore, he became not only a reliable partner and a rich man, but also a good father, husband and lover.

I had to go a long way before I found myself.

After all, when adults raise children incorrectly, the children cease to love not the adults, but themselves.

I wrote my story especially for my intended husband. And I was preparing myself for him to change his mind about marrying me after reading it. But that did not happen.

Could it be that if a person is able to coherently describe a situation, it means they have coped with it?

A CULT WITHIN A CULT

I used to get annoyed when friends and acquaintances questioned me about my childhood. Every time I started to answer, someone would immediately interrupt me, and from their very first question it was clear they didn’t believe me. Or the question was so painful that I got angry and snapped at them. And sometimes I myself began to doubt whether I was telling the truth: maybe I had embellished it, maybe my memory was distorted over time under the influence of emotion. More than once I tried to check by asking someone else who was in the cult with me as a child. Unfortunately, not only did everyone I ask confirm my memories, but they also added their own.

However, when talking with people who came to the cult as adults, I noticed their impressions differed from the memories of those who had spent their childhood there. Moreover, they can be divided into several types.

Some experienced guilt and did not hide it. It was obvious the memories were very unpleasant for them. In my opinion this is the normal reaction of a normal person.

Others avoided direct answers, answered inappropriately, or turned everything into an angry, sarcastic joke. They didn’t want to remember. My stepfather was one such. In principle, this is also a normal reaction, although it indicates indifference and a lack of empathy.

Still others, instead of actually answering, insulted me. This was the majority.

A fourth group rolled their eyes meaningfully, as if to say I must be narrow-minded and limited not to understand the deeper meaning of everything that happened there. Like I didn’t get it while I was there, and I never got it after that. They didn’t manage to cure me. It was of people like this that the backbone of the cult consisted. Everything rested on them. And it rests on them to this day.

Only now, having left Russia forever, am I beginning to realise that all those sectarian attitudes have spread everywhere, and continue to spread, like mould…

We left the cult, we condemned it in words, but it remained in us and with us; we continued to live according to its principles. We judged things in the same way, we treated ourselves in the same way, we thought in the same categories, we acted with the same attitudes and built our lives in accordance with them. Our fear of the unknown, of what we cannot control – mental disorders, physical illness and death – is primordial and nurtured by a system inherited from the concentration camp conditions of the Soviet Union.

And every time I tried to dissociate myself from this, to simply physically move further away, I was “kicked out” from the team, as if making it clear:

“We don’t need another you. If you are not completely with us, then you are against us. So you are the enemy.”

A 40-YEAR JOURNEY

The first time I made notes about my childhood in the cult was when I was 23, just so as to not forget the details. I already knew then that it would be something of a thought experiment on myself. And I also knew that what I wrote down as memories was true, but what I wrote down as evaluation was not true. But back then I didn’t know other words. I didn’t know how to name my emotions, or how to cope with them. I couldn’t label them. I was only 23, and there was no one around to help me sort out my feelings. I was driven by a desire to recall at least something good about my family, about my parents who had sent me to the cult. I tried my best to find an excuse for them.

Now I’m 45. I no longer live in the USSR, I no longer even live in Russia. My daughter is already 15. My family is now also completely different; it is Scandinavian and Swiss. My husband is Norwegian and we live in Switzerland. My husband has his own business, his own private university and business school, and I have my own business in publishing books. We are committed to educating people.

I moved to the West not only physically, but also mentally. And now I only ever look East out the corner of my (narrowed) eyes.

Анна Сандермоен

When eight-year-old Ania is sent to stay with her grandmother for the summer holidays, she finds a house full of strangers and a grandmother who pretends not to know her. Ania only returns home six years later. This autobiography is about childhood in an illegal cult in the USSR, involving the scientific and creative elite of the Soviet Union. The cult's leader, V. D. Stolbun, claimed to be raising a breed of superhuman immune to any physical or mental illness. Any totalitarian cult is built on a strict hierarchy and is controlled entirely by its leader, whose only motive is power. This is a book about adults betraying the children in their care. It warns us to be wary of anyone who claims to be "saving the world", and contains tools to identify a cult before it is too late. The author managed to free herself from the puppetmaster's grip, but his appalling activities continue to this day. Содержит нецензурную брань.

Анна Сандермоен

The Cult in my Grandmother's House

ANNA SANDERMOEN

THE CULT

IN MY GRANDMOTHER’S HOUSE

Translated from Russian

by Stephanie Droop

Introduction by Kjetil Sandermoen

The story you are about to read was written by my dear wife Ania. It is a true story about a large part of her childhood, and I am sure it will move and impact you.

Among a lot of incredibly shocking anecdotes in this book, the one that touched me the most is where Ania describes how she was sent back to her grandmother’s house, so full of happy and joyful memories, only to find it full of strangers living there in what turned out to be a cult, and her loving grandmother now treating the young girl as if she was an unwanted stranger. That Ania has chosen to call her book The Cult in my Grandmother’s House is probably evidence that this particular part of her story affected her deeply as well.

When I met my wife and she eventually told me just a little bit about her background of growing up in a cult, I must admit I had to discuss with myself how this could have given rise to fears and problems that she would bring with her into our relationship.

Ania is a very strong and proud person and it is not her habit to focus on the negative aspects of life. The childhood stories that she usually shares with friends and family are the fun and nostalgic ones. However, I know that the years taken from her childhood spent in a cult is a painful past that she will always bring with her. I have therefore encouraged her to write this book about these years. It can stand as a warning to any adult who would contemplate joining a cult or a sect, or – as in Ania case even worse – sending your child away to a cult. I believe that writing the book is also a part of a healing process for Ania. It is a story worth writing down and indeed a story worth reading.

Any kind of cult is dangerous and destructive. The core of a cult is sectarianism, which is the idea that members of the cult are convinced that their salvation and success, based on their particular objectives, aggressively require to find converts from outside the cult in order to succeed with their political, religious or ideological project. It is always based on a very oppressive hierarchy, almost always under the dictatorial leadership of a charlatan whose motives are dominance, power, and sexual and material privileges.

The cult that Ania describes in this book is in my opinion extraordinarily dangerous since it claims it can cure disorders like schizophrenia and fatal diseases like cancer. The idea was that children are spoiled and become “weak” by being brought up by their parents and therefore have to be taken care of by strangers. Illness is (according to this cult) a result of negative thinking by weak humans. The leader claimed that the whole world was suffering from schizophrenia (he made a big market for himself). Only his wisdom could cure it.

These ideas were unfortunately in unison with the prevailing ideology of the USSR where they wanted to diminish the family and replace it with upbringing by the Communist Party to create the Homo sovieticus. In the USSR people were also readily accused of being schizophrenic and sent away for forced “treatment” if they had the courage to stand up against this totalitarian system.

I have observed that still today any mental disorder is nonchalantly labelled “schizophrenia” in Russia. It is as if it is not completely understood that this is a very serious, disabling and incurable psychiatric disorder. Schizophrenia involves a number of serious problems with thinking, behaviour or emotions and it requires lifelong medication and treatment. I am absolutely confident that very few – if any – members of this cult were actually suffering from schizophrenia. However, they were manipulated into obedience and treated with ridiculous methods by dilettantes.

As I understand it, this cult still exists and practices its unauthorised “treatment” in the middle of Moscow.

The worst emotional pain a child can experience is to feel abandoned by her parents. Children do not have a choice. A child cannot choose her parents and she cannot choose what is done to her. However, even when let down and treated unfairly, children are equipped with an incredible ability to love their parents. I know that Ania does not feel any hate towards her parents or anyone else. It is not up to me to cast judgments about what Ania parents did to her. The times and the conditions in the USSR were so completely different from anything I myself grew up with, that I can hardly comprehend it. I do believe however, that Ania feels disappointment and an emptiness in her heart where the love for her parents should have been. I do my best to help Ania in finding a perspective in this regard. The best healer however would have been just an honest, “I am sorry for what happened, we did wrong to you”. That would have meant a lot for Ania.

Read, reflect and learn from this excellently written book.

Kjetil Sandermoen,

September 03, 2019

Zug, Switzerland

Foreword

Under tyranny it is much easier to act than to think.

Hannah Arendt, philosopher

WHO AM I?

I am a capricious, selfish, critical and permanently dissatisfied little bitch. I’m a materialistic, opportunistic animal, always calculating a few steps ahead. I’m a bourgeoise. At least, this is what I was assured of right from childhood, extensively and persistently, and, I must admit, very successfully.

But once, to my great surprise, my husband told me he liked the fact that I wasn’t some spoilt little European thing, but a steely Russian with a good (albeit a little strange) sense of humour.

I was 39 years old when he proposed to me, and I thought it would be dishonest on my part to unite my life with a person without telling him about my past, about my childhood. I wouldn’t be able to keep silent about this all my life, and if I told him it in snatches, then he might have formed an incomplete or even wrong impression of me. That might have been fine if he was Russian – Russians aren’t fazed by most far-out stories. But he is Norwegian, and he was raised in a decent family, in the sort of abundance I never dreamed of, and, most importantly, surrounded by love and care. A decent environment gave him moral guidance; wealth fostered his severe self-discipline; and love and care made his heart responsive. Therefore, he became not only a reliable partner and a rich man, but also a good father, husband and lover.

I had to go a long way before I found myself.

After all, when adults raise children incorrectly, the children cease to love not the adults, but themselves.

I wrote my story especially for my intended husband. And I was preparing myself for him to change his mind about marrying me after reading it. But that did not happen.

Could it be that if a person is able to coherently describe a situation, it means they have coped with it?

A CULT WITHIN A CULT

I used to get annoyed when friends and acquaintances questioned me about my childhood. Every time I started to answer, someone would immediately interrupt me, and from their very first question it was clear they didn’t believe me. Or the question was so painful that I got angry and snapped at them. And sometimes I myself began to doubt whether I was telling the truth: maybe I had embellished it, maybe my memory was distorted over time under the influence of emotion. More than once I tried to check by asking someone else who was in the cult with me as a child. Unfortunately, not only did everyone I ask confirm my memories, but they also added their own.

However, when talking with people who came to the cult as adults, I noticed their impressions differed from the memories of those who had spent their childhood there. Moreover, they can be divided into several types.

Some experienced guilt and did not hide it. It was obvious the memories were very unpleasant for them. In my opinion this is the normal reaction of a normal person.

Others avoided direct answers, answered inappropriately, or turned everything into an angry, sarcastic joke. They didn’t want to remember. My stepfather was one such. In principle, this is also a normal reaction, although it indicates indifference and a lack of empathy.

Still others, instead of actually answering, insulted me. This was the majority.

A fourth group rolled their eyes meaningfully, as if to say I must be narrow-minded and limited not to understand the deeper meaning of everything that happened there. Like I didn’t get it while I was there, and I never got it after that. They didn’t manage to cure me. It was of people like this that the backbone of the cult consisted. Everything rested on them. And it rests on them to this day.

Only now, having left Russia forever, am I beginning to realise that all those sectarian attitudes have spread everywhere, and continue to spread, like mould…

We left the cult, we condemned it in words, but it remained in us and with us; we continued to live according to its principles. We judged things in the same way, we treated ourselves in the same way, we thought in the same categories, we acted with the same attitudes and built our lives in accordance with them. Our fear of the unknown, of what we cannot control – mental disorders, physical illness and death – is primordial and nurtured by a system inherited from the concentration camp conditions of the Soviet Union.

And every time I tried to dissociate myself from this, to simply physically move further away, I was “kicked out” from the team, as if making it clear:

“We don’t need another you. If you are not completely with us, then you are against us. So you are the enemy.”

A 40-YEAR JOURNEY

The first time I made notes about my childhood in the cult was when I was 23, just so as to not forget the details. I already knew then that it would be something of a thought experiment on myself. And I also knew that what I wrote down as memories was true, but what I wrote down as evaluation was not true. But back then I didn’t know other words. I didn’t know how to name my emotions, or how to cope with them. I couldn’t label them. I was only 23, and there was no one around to help me sort out my feelings. I was driven by a desire to recall at least something good about my family, about my parents who had sent me to the cult. I tried my best to find an excuse for them.

Now I’m 45. I no longer live in the USSR, I no longer even live in Russia. My daughter is already 15. My family is now also completely different; it is Scandinavian and Swiss. My husband is Norwegian and we live in Switzerland. My husband has his own business, his own private university and business school, and I have my own business in publishing books. We are committed to educating people.

I moved to the West not only physically, but also mentally. And now I only ever look East out the corner of my (narrowed) eyes.