По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

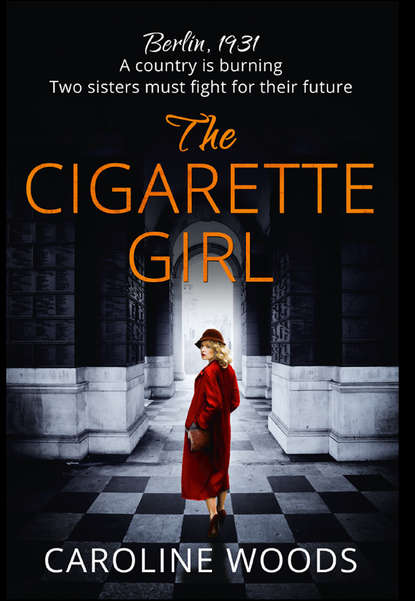

The Cigarette Girl

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

For years they’d slept beside each other, even though the sisters liked to arrange girls by age. They’d come to St. Luisa’s when Berni was four and Grete two, after their mother died and they could no longer stay at her cottage in Zehlendorf. Berni remembered the smells of her mother’s home best: cedar chests opened in winter, nutmeg shaved over hot milk. As a baby, blond Grete also had a milky scent, and a fear of thunderstorms; as soon as she could toddle, she’d climb from her trundle into Berni’s carved wooden bed.

At times, Berni could not help feeling that her real life was a kind of river she was always running alongside, searching for a place to leap back into the water and be carried along by the current, back to her mother, Trudi. It was Trudi’s elder sister, a spinster whose name Berni would no longer utter, who had dumped them at St. Luisa’s. She’d come to live with them when Trudi fell ill with pneumonia and saw her through her death. The aunt stank of something briny and woke late every morning without feeding the girls. The last time they’d seen her, she’d been crying in the reverend mother’s office, hanky to her nose, saying she couldn’t do it anymore.

“Are you certain, Berni?” Grete asked once, chewing a fingernail. “That wasn’t our mother who gave us to the sisters, after our father died. Was it?”

“Hush! Mother can hear you in heaven.” Of course it hadn’t been their mother. Berni could vividly remember the first time she’d seen St. Luisa’s. It sat on a bleak corner in otherwise affluent Charlottenburg, gray as a prison, with rows of too-small windows. The trim, painted strenuous red, gave the building a stressed, weeping face, and Berni had known instantly they were in trouble. She’d given their aunt a good kick in the shin.

“Tell me a happy story,” Grete whispered now. Under the bedcovers her feet tickled Berni’s shins, her toenails poking through her holey socks.

“Once upon a time there were two sisters, Snow White and Rose Red. Schneeweißchen preferred the hearth and home; Rosenrot played outside and gathered berries for their mother.”

“No,” Grete said. “One about our mother.”

“Ahem. Once upon a time, in Zehlendorf, there lived a young woman who raised squab in a shaded dovecote in her backyard. She had two little girls who slept in the attic under the eaves: Bernadette and Margarete, one tall and raven-haired, one fair and small.”

“How did the dovecote smell?”

“It smelled foul, and so the mother planted wildflowers all around it.” Berni had recited the story so often she could see discarded feathers on grass. “One day, a magician came to the house. The young mother held baby Grete against her side and took Bernadette by the hand. ‘Choose the whitest birds you can find, my sweet, the ones with the most magic,’ she told Bernadette. The magician took them away with a sweep of his cape.”

“She was a kind mother.”

“Very kind,” Berni said. She did not have to recite the next part of the story, the one they knew best. Their mother had been very kind to introduce them to the magician; she did it to hide the real reason she raised their beloved doves, which was for meat.

• • •

So much money. Berni dreamt about it, woke up licking her lips. She felt it crunch between her fingers, under the sheets.

She didn’t tell Grete what she intended to do until Thursday evening, when Sister Maria marched out on her weekly mission to feed the poor and Berni’s accomplice, Konstanz, met them in the dormitory. “Sister’ll be out until eight, at least,” Konstanz announced. She had wide green eyes and a willowy build, more fairy than child. “You aren’t going to tell, are you, Grete?”

Grete had both hands over her ears, the corner of a blanket in her mouth. Berni knelt down, close to her face. “Nothing bad will happen. She has so much money she can burn it.” She couldn’t explain her need to possess something, anything, even if it did turn out to be worthless.

“Why must you always put us in danger?” Grete tilted her watery eyes toward the ceiling and sighed. “Every night I wish the next day will be quiet, every night . . .”

Before long, Berni was pulling Grete down the quiet corridor. Konstanz led the way, grabbing corners as the girls slid through the halls. At last they reached the east wing, where they tiptoed past the wooden doors to the sisters’ rooms. Berni put her arm around Grete, whose face had turned the color of bathwater, as Konstanz worked a hairpin into the lock. When finally the handle gave, Berni entered the room quickly and lifted the shade. Gray evening light illuminated the cot, the desk, the heavy crucifix. Sister’s laundry was folded atop her sheet.

“I don’t know why, but”—Konstanz’s eyes widened—“I never would have imagined they wore underwear.” Some of the bloomers were even faded pink, large and dainty at once. On a rough wooden table sat a teapot and tiny mug. Berni opened the pot to peek at the stiffened tea bag inside. She ran her finger over the edge of the cup to feel the greasy print of the sister’s lip.

“Let’s go,” Grete whispered. Berni pretended she hadn’t heard.

“Look at this.” Konstanz threw off a radio’s cover. It looked like a large wooden jewelry box with black dials. “It’s a TRF set. My father had one.” She began to adjust the reactor.

“Come, Grete.” Berni picked up the desk chair by the rungs. “You need to be closer to the sound.” Grete glared at her, face deep red, as she took her seat.

When a song burst out of the radio, they all leapt back. “Turn it down, turn it down!” Berni cried. She yanked Grete’s hands from her ears, trying to get her to smile.

“And now,” a voice announced when the music faded, “Frieda Pommer and Max Zuchmayer singing their popular duet, ‘If I Could Choose Again.’”

A lively tune began: horns, strings, accordion. Konstanz leapt into the middle of the room, landing soundlessly as a cat, and curtsied; she would be Frieda Pommer. She put one hand on her hip and glided her mouth over the words as if she’d heard them all her life:

A skinny man approached me to see if I’d be his bride.

A poor man with a good heart said that heart was free, but lied.

I’d gladly dance with either, but I’m already obliged

To a portly chap in uniform who has something to hide.

Berni was enthralled. The lyrics did not make her think of politics, only of men and marriage, of dancing and wine. She and Konstanz kept their shrieks silent and clapped without sound. Konstanz twirled and goose-stepped, and when Max began to sing, Berni stood.

She could not have said where the idea came from. If she had known how Grete would react, or what would come after, she never would have done it. She wasn’t even sure how or when she’d learned what made men different from girls, but she snatched a rolled-up stocking off Sister Maria’s bed and stuffed it into her underpants.

Konstanz put her hands over her eyes, giggling. Then Frieda looped back to the chorus, and Konstanz threw back her head. She and Berni linked arms, and Berni thrust her little crotch this way and that, hands on her hips like a Prussian soldier, the sock forming a bulge under her skirt. She had tears streaking her cheeks, her tongue pumping silently in her mouth.

Round and round she and Konstanz went, in dizzying circles—the dull Spartan room a blur, the only color the shockingly intimate laundry on the bed and the bright yellow of Grete’s hair, until—

The radio’s volume shot sky-high, blasting Frieda Pommer’s voice throughout the building.

Berni whirled around. Grete’s sticky fingers held one of the dials, and her mouth was pressed shut. She stared past Berni, at nothing. Berni had completely forgotten her as she danced.

Konstanz cried out, covering her ears. Berni tore the stocking from under her skirt and whipped it at the bed, then slapped Grete’s hand away and shut the darn thing off. Too late; she could hear the sisters’ doors opening, could hear their alarmed voices.

“If you wanted me to stop,” Berni murmured, “you could have just said so.” But Grete wouldn’t answer. She wouldn’t meet Berni’s eyes, not even when Sister Odi burst triumphantly into the room.

Grete, 1931 (#ulink_6ec77b6c-784c-51bd-a8e0-91ef723e33d6)

They were stopped on a corner of the Kurfürstendamm, the busiest shopping street in the city. A place where they very decidedly did not belong, Grete thought. Their clothes gave them away; donated dresses did not grow at the same weedlike pace that girls did. Strings hung from Berni’s broken hem, and still the fabric did not cover her knees.

Berni didn’t seem to notice. Her hand shielding her eyes, she had the optimistic, faraway look of a sea explorer. She held the last of the three boxes of communion she’d been asked to deliver to churches in west Berlin, Grete the red cash tin. Berni had been ordered to return to the home in time for lunch. Grete was not supposed to be out at all.

“Can you read the time, Grete-bird?” Berni pointed to the clock on the Memorial Church, its stones blackened with city pollution.

Grete squinted up at the gold numerals. For a moment, she considered telling a lie to get Berni moving. “Eleven thirty,” she said honestly. “We need to go home, Berni.”

“Eagle eyes!” Berni bent down so that her lips touched Grete’s earlobe. “That means we have time,” she said in a low voice, affecting an Eastern accent, “to visit Libations of Illyria.”

A blade of fear stabbed Grete’s stomach. “Please, no. Let’s find St. Matthias, then take the U-Bahn home before anyone notices I’m missing.” She leapt back when an omnibus lumbered to the curb, sending oily water toward her shoes.

Earlier in the day she’d been peacefully changing beds in the nursery when Berni burst into the room. Grete would join her, she declared without asking, on her communion-delivery adventure. It was something to celebrate, Berni insisted: the sisters entrusting her with the communion wafers the Lulus baked, worth more than a pfennig apiece, meant they were on the verge of choosing her for the academy.

Grete had given her usual excuses, knowing they would not deter Berni: she had to carry soiled sheets up to the laundry, she had a Latin exam to study for. Tomorrow, Sister Maria would fire questions at her in Latin, standing behind the dais so that Grete could not see her mouth. Her only hope was to study until she could recite the whole dead language in her sleep, and here was Berni, pressuring her to go on one of her larks. But Berni promised they’d practice this evening; she’d have Grete speaking like Julius Caesar by the end of the night.

“Come, one more detour,” Berni said now, shielding Grete from two women in trousers walking and smoking, moving at breakneck speed. “I’ll buy you a pretzel.”

Bells tinkled, and a young man rode by on a bicycle. He tossed some change into a homeless veteran’s cap. Grete had seen only the thin white arms of the cyclist’s companion, clasped around his waist. Watching them, Berni’s face took on a look of naked yearning. It seemed she longed for those pale arms to belong to her.

Grete pulled at her sleeve. Berni had to remember they weren’t both Rose Red. Somebody had to be Snow White. “I must prepare for Latin.”

“This is more important.”