По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

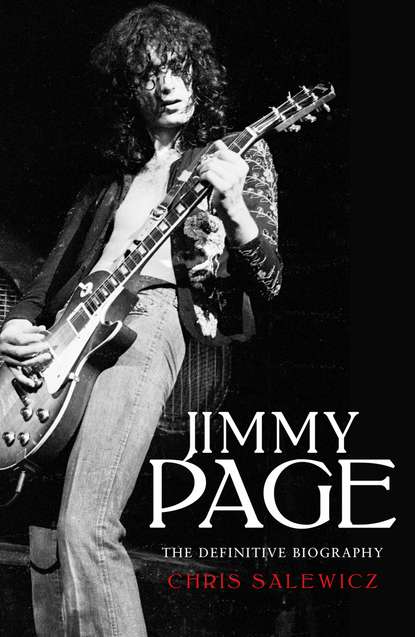

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The tune was ‘Beck’s Bolero’. Maurice Ravel’s Boléro, which was first performed in 1928 at the Paris Opera, provided the basis for ‘Beck’s Bolero’; the Russian ballet dancer Ida Rubinstein had commissioned Ravel to write the work, an undulating, insistently repetitive piece based around the Spanish music and dance known as bolero.

By 1965, largely influenced by the tastes of the likes of Paul McCartney, always an assiduous culture vulture, assorted classical composers had become fashionable among fans of what formerly would have been known as ‘pop’. These composers included Bach, Sibelius, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Gershwin, Debussy and Ravel, whose Boléro was relatively well known in 1966. The song’s structure is considerably amended in such a way that it could be interpreted as the first blow of the hard-rock sound that Led Zeppelin would very soon develop.

‘Beck’s Bolero’ employed a formidable cast: Beck on lead guitar, Page on acoustic, revered session pianist Nicky Hopkins, the Who’s Keith Moon on drums and John Paul Jones on bass. The Who’s John Entwistle, Moon’s bass-playing rhythm partner, had originally agreed to do the session, but when he failed to turn up John Paul Jones was called in.

‘I heard rumours that Jimmy was talking with Keith Moon about joining his supergroup,’ said Napier-Bell. ‘I don’t think the name Led Zeppelin was in the air at that time, though it may have been mentioned between them. Cream was being formed at the same time. Whether that had much influence on Beck, Page and Moon, I don’t know. The Who’s managers, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, were in the same building as Clapton’s manager, Robert Stigwood. So when he was putting Cream together, they would have known all about it, as I did too. Keith Moon would have heard from Kit and Chris as to what was going on too. From my point of view, I was thinking only of keeping Jeff in the group [the Yardbirds]. Jimmy, I think, was thinking of a new group, which would be a blend of all their talents.’

‘I always try to do things wholeheartedly or not at all,’ said Beck, offering a slight rewrite of history, ‘so I tried to imagine what my ideal band would be. We had the right producer, Keith Moon on drums, Jimmy on guitar and John Paul Jones on bass. You could feel the excitement in the studio, even though we didn’t know what we were going to play. I thought, “This is it! What a line-up!” But afterwards nothing really happened because Moony couldn’t leave the Who. He arrived at the studio in disguise so no one would know he was playing with another band.’

‘Jim Page and I arranged a session with Keith Moon in secret, just to see what would happen,’ said Beck. ‘But we had to have something to play in the studio because Keith only had a limited time – he could only give us like three hours before his roadies would start looking for him. I went over to Jim’s house a few days before the session and he was strumming away on this 12-string Fender electric that had a really big sound. It was the sound of that Fender 12-string that really inspired the melody. And I don’t care what he says, I invented that melody. He hit these Amaj7 chords and the Em7 chords, and I just started playing over the top of it … He was playing the bolero rhythm and I played the melody on top of it, but then I said: “Jim, you’ve got to break away from the bolero beat – you can’t go on like that for ever!” So we stopped it dead in the middle of the song – like the Yardbirds would do on “For Your Love” – then we stuck that riff into the middle. And I went home and worked out the other bit [the uptempo section].’

‘Even though he said he wrote it, I wrote it,’ said Page, presenting an argument that would become somewhat familiar.

‘Moon did this amazing fill around the kit, and a U47 mic just left its stand and went flying across the room; he just cracked it one,’ said John Paul Jones.

‘I remember Jimmy at the studio yelling at us and calling us fucking hooligans,’ said Beck. ‘Everyone had prior commitments. That session that day, it was one day that really started my head turning – we were almost doing it.’

That band, claimed Beck, was the original Led Zeppelin – ‘not called “Led Zeppelin”, but that was still the earliest embryo of the band’.

‘It was going to be me and Beck on guitars, Moon on drums, maybe Nicky Hopkins on piano. The only one from the session who wasn’t going to be in it was Jonesy, who played bass,’ said Page. ‘It would have been the first of all those bands, sort of like Cream and everything. Instead, it didn’t happen – apart from the “Bolero”. That’s the closest it got … The idea sort of fell apart. We just said, “Let’s forget about the whole thing, quick.” Instead of being more positive about it and looking for another singer, we just let it slip by. Then the Who began a tour, the Yardbirds began a tour, and that was it.’

In fact, there had been some efforts by Page and Beck to find an appropriate vocalist to transmogrify the ‘Beck’s Bolero’ studio line-up into a working outfit, as Page told Guitar World’s Steve Rosen: ‘Well, it was going to be either Steve Marriott from the Small Faces or Steve Winwood.’ Marriott was managed by Don Arden, the self-styled ‘Al Capone of pop’. ‘In the end, the reply came back from his office: “How would you like to have a group with no fingers, boys?” Or words to that effect.’ Sufficiently warned off, the pair never even approached the Spencer Davis Group’s Steve Winwood.

There was even controversy over the ‘Beck’s Bolero’ production credit. Mickie Most claimed it, part of a contractual issue between him and Beck, his managerial client. Simon Napier-Bell would insist it was his, and Jimmy Page claimed that he had done the record’s production, staying behind in the studio long after Napier-Bell had gone home.

‘The track was done and then the producer just disappeared,’ Page told Steve Rosen in September 1977. ‘He was never seen again: he simply didn’t come back. Napier-Bell, he just sort of left me and Jeff to it. Jeff was playing and I was in the box [studio]. And even though he says he wrote it, I’m playing the electric 12-string on it. Beck’s doing the slide bits, and I’m basically playing around the chords.’

Simon Napier-Bell has a different point of view. ‘Jimmy Page was being demeaning when we were making the record: he was sneering. Later, when Beck and Page were discussing how the mix should be, I went away to leave them to it. The purpose of a producer is so that the record ends up as it should. That’s why I went away – to leave them to it. As for Mickie Most, my agreement with him over the management of the Yardbirds was that all product reverted to him. I just said, “What the hell, I don’t need it.” I didn’t really – but that track became a rock milestone.’

When Pete Townshend discovered that Keith Moon had played on the session, he was furious. He began to refer to Beck and Page as ‘flashy little guitarists of very little brain’. Page’s response? ‘Townshend got into feedback because he couldn’t play single notes.’ Townshend later commented: ‘The thing is, when Keith did “Beck’s Bolero”, that wasn’t just a session, it was a political move. It was at a point when the group was very close to breaking up. Keith was very paranoid and going through a heavy pills thing. He wanted to make the group plead for him because he’d joined Beck.’

Later, it was claimed that Moon had declared that if the studio line-up became an actual band, it would go down ‘like a lead balloon’. According to Peter Grant, Entwistle then added, ‘like a lead zeppelin’. (Entwistle was always adamant that he came up with the Lead Zeppelin name all on his own; and also that he had the idea of a flaming Zeppelin as an album cover.)

When writing his Keith Moon biography Dear Boy, Tony Fletcher interviewed Jeff Beck about the ‘Beck’s Bolero’ session. Fletcher asked Beck if Moon had been using him to pressure the Who for his own ends. Beck replied that that wasn’t the case at all: the subtext to the ‘Beck’s Bolero’ session was the relationship between Jimmy Page and himself: ‘No, it was something to do with Jimmy and me. I had done sessions for Jimmy. He used to get me to do all the shit he didn’t want to do. He used to get me to pick him up in my car and pay for the petrol, and I’d find out he was on the session anyway. When he heard what I was doing on the sessions … he started taking an interest in my style, and then we went from there. And then the Yardbirds got in the way – I can’t remember the sequence of events. I remember thinking, “Why can’t I have what I want instead of what I’ve got?” That’s always the way. To have someone who’s so musically aware and talented as Jim alongside me was something I could really do with. But that wasn’t to be until later on in the Yardbirds. Meanwhile, I’m watching the Who going from strength to strength with a fantastic powerful drummer and knowing that that was what I really needed to get myself going. So it was a guiding light in one sense and fragmented what I already had. I was never content being in the Yardbirds, and I left Jim to paddle his canoe in the Yardbirds.’

The Yardbirds’ rhythm-guitar player Chris Dreja was yet another denizen of the Surrey Deep South from which Page, Clapton and Beck hailed. Brought up in Surbiton, where he continued to live, he would from time to time run into Page while the guitarist was studying at Sutton Art College. On more than one occasion he came across him in nearby Tolworth, outside the tropical-fish shop: Page was a tropical-fish enthusiast. ‘Hello, Chris, I’ve just bought a nice thermometer for my fish,’ he once greeted him.

On 18 June 1966 Page travelled up to Oxford in the passenger seat of Jeff Beck’s maroon Ford Zephyr Six to watch his friend play with Chris Dreja and the other Yardbirds at the May Ball at Queen’s College. They were on the same bill as seasoned Manchester hitmakers the Hollies. Not that that ‘seasoned hitmaker’ rubric couldn’t also have been applied to the Yardbirds. Since Beck had joined the band it seemed like they were never out of the UK charts – and increasingly the US hit lists were also welcoming the group’s 45s: ‘Heart Full of Soul’, ‘Evil Hearted You’, ‘Shapes of Things’ and ‘Over Under Sideways Down’ had all been hit singles. Meanwhile, their critically acclaimed Yardbirds album – more generally known as Roger the Engineer – was about to be released in the middle of July 1966.

Although events such as the May Ball paid well, they were formal, black-tie occasions, in the main quite uptight and, as defined in the new underground vocabulary, extremely ‘straight’. Becoming increasingly drunk as the evening progressed, Keith Relf, the Yardbirds’ singer, took exception to this prevalent social posture, and he began to harangue and berate his audience of bright young things. It was a stance that Page, notwithstanding his fondness for tropical fish, always a rebel and in tune with the more esoteric minutiae of pop culture, admired greatly: he thought Relf put on ‘a magnificent rock ’n’ roll performance’. Paul Samwell-Smith, the Yardbirds’ bass player, was so appalled by Relf’s stance, however, that as soon as their show was over he quit.

With further dates coming up, the Yardbirds were concerned about how they could play them without a bass player. On the spot, Page volunteered his services. ‘They had a show at the Marquee Club, and Paul was not coming back. So I foolishly said, “Yeah, I’ll play bass.” Jim McCarty says I was so desperate to get out of the studio that I’d have played drums.’

For some time Page had harboured doubts about whether he could continue working as a session player. ‘My session work was invaluable. At one point I was playing at least three sessions a day, six days a week. And I rarely ever knew in advance what I was going to be playing. But I learned things even on my worst sessions – and believe me, I played on some horrendous things. I finally called it quits after I started getting calls to do Muzak. I decided I couldn’t live that life any more; it was getting too silly.’

‘I remember the May Ball,’ said Beck. ‘Jimmy Page actually came to that gig. He came to see the band and I told him things were not running very smoothly. There were these hello-yah Princess Di types around. Trays with drinks with sticks. And as soon as we started Keith fell over back into Jim’s drums. After, I said, “Oh sorry, Jim, I suppose you’re not interested in joining the band?” He said it was the best thing ever when Keith fell back into the drums. It wasn’t going to put him off that easily.’

And so, slightly oddly, Jimmy Page joined the Yardbirds. That Marquee show took place three days later, on 21 June. How was Page’s performance? Terrible, according to Beck. ‘Absolute disaster. He couldn’t play the bass for toffee. He was running all over the neck. Four fat strings instead of six thin ones.’

Whatever. As soon as Page became a part of the group, he changed his look entirely: he presented himself as a highly stylised, very chic rock star, someone of ineffable good taste and class. And very quickly, with his characteristic diligence, he became adept on the bass guitar.

Before Page formally joined the Yardbirds, he went round to Simon Napier-Bell’s flat in Bressenden Place, near Buckingham Palace, for a meeting with the group and their manager. ‘When he arrived,’ said Napier-Bell, ‘he had an enormous swollen lip. Nobody knew who’d done it. He said some people had stopped him in the street and hit him. I remember thinking that if you’re Jimmy Page that could happen to you because of your sneering. Jimmy’s superciliousness was hard to take. When Jimmy Page looked as nice as he does, maybe he thought he could get away with it.

‘He came into the group. I said, “We don’t really get on.” “You’re my manager: I want to see the contract,” he said. I said, “You won’t. I’ll take my percentage off four-fifths of the money, and I won’t manage you.” Because I knew he would want to pull a stunt and say the contract was terrible.

‘I always thought Jimmy Page was partially gay. He didn’t have a great childhood: because he was such a cunt, you knew he didn’t have a great childhood. And later he got into transvestism. Which meant he thought he was straight.

‘I said to Jeff Beck, “Jimmy Page is coming in to the Yardbirds and you will leave.” He said, “No, I won’t.”’

Although ‘Jeffman’ had been proprietorially spray-painted onto the rear of the Telecaster Beck had gifted him, Page customised the instrument, giving it a psychedelic colour-wash, adding a silver plate to catch stage lighting and reflect it back at the audience, a simple but extraordinarily effective trick. For some time this Telecaster became identified with Page.

Yet before he could graduate to playing this guitar with the Yardbirds, Page remained the group’s bass player. It must have been a baptism of fire: vocalist Keith Relf, an asthmatic, would drink all day, the singer’s inner turmoil perhaps exacerbated by the fact that, oddly, the Yardbirds’ tour manager was his own father. Between the Marquee show and the end of July, the Yardbirds played 24 dates, all over the UK. For Page it must have been like getting back on the gruelling road with Neil Christian and the Crusaders. There was a show with the Small Faces in Paris on 27 June, and a set of dates in Scotland early in July; at one of these Beck and Page were spat at for wearing the German Iron Cross. Couldn’t these former art students have explained that they were simply indulging in a spot of street-level conceptual art? (Or perhaps it was an indication of chronic immaturity? A decade later comparable attempts at shock would be made by the likes of punk stars Sid Vicious and Siouxsie Sioux, similarly employing Nazi regalia. As with the Yardbirds’ efforts, wouldn’t you consider this to be comparable to naughty ten-year-olds drawing such images on their school exercise books?)

Although he had his flat off Holland Road in west London, Page was still frequently staying at his parents’ house in Epsom. But in the mid-sixties his parents separated and then divorced. This brought great pain to their son. Moreover, shockingly, his father had been living a double life: he had created a separate family with another woman. This would have been devastating news. ‘You would never trust anyone again, especially intimate people,’ commented Nanette Greenblatt, a renowned London life coach. ‘In any relationship you were in, you would be worrying, “This is okay for now, but how will it turn out?” Accordingly, you would want to control people. There would be a strong distrust of male figures. And Aleister Crowley would fit in nicely as an unreliable father figure.’

The kind of trauma to which Page and his mother were subjected by this egregious information about his father must have been almost overwhelming. But, just as a new birth is said to bring good luck, so a figurative death in the shape of divorce can sometimes offer the opportunity for a phoenix-like rise to escape the grief of the event. Something like that happened to Page. Some constraints fell away, to expose a desire for the ultimate promulgation of who he could be, and how far he could take it. You can have this fantasy image of yourself, which, if you work hard enough at it, is what you become. In other words, find your true will: who you are meant to be in this existence and what you are here for – the meaning of Crowley’s ‘Do what thou wilt’, appropriated almost predictably from a freemasonry text. Once upon a time, ‘Jimmy Page’ was a construct in Page’s own mind. But because he meant it, and, more importantly, needed it, it became him, and he it. With some assistance from his beliefs, of course.

5

BLOW-UPS (#ulink_900e2b81-18eb-519a-8416-def067a761c5)

Jimmy Page finally moved away from his childhood home. First, he took the flat off Holland Road in Kensington. But part of the mood of the age was the need to connect communally with the essence of the earth, a need that would later be expressed by the likes of the Band, who creatively isolated themselves in Woodstock in upstate New York, and the English group Traffic, fronted by Page’s friend Steve Winwood, who wanted to ‘get it together’ in a cottage in rural Berkshire.

And it was to that same verdant county of Berkshire that Page now moved. Kenneth Grahame, author of the children’s classic The Wind in the Willows, had retired to Pangbourne, situated on the River Pang four miles west of Reading, in later life, and now Page made the village his home, buying a former boathouse on the river, water frequently being close to the homes he would purchase, solace for his Scorpio rising. Later, he would develop a reputation for being to some extent a recluse; it was here that such an existence was first nurtured, one he found creatively beneficial. ‘I really enjoyed that bachelor existence – working and creating music, and going out on my boat at night on my own; switching off the engine and just coasting in the twilight. I liked all that,’ he told the Sunday Times. His tank of tropical fish survived the journey from west London, although his long absences away on the road eventually obliged him to give up this hobby.

And anyway, Page was almost straightaway off on the road again. This time it was to the United States.

That same month, June 1966, someone else demonstrated an intriguing element of experimental good taste – unsurprisingly, given that the record was produced by Shel Talmy, Page’s longtime studio champion, a master of innovation. ‘Making Time’, the stunning, sneering tune in question, was released by a Hertfordshire group called the Creation; Eddie Phillips, the guitarist, would at times play his instrument with a violin bow. It has long been alleged that Page took note of this and copied the effect. ‘Eddie Phillips deserves to be up there as one of the great rock ’n’ roll guitarists of our time, and he’s hardly ever mentioned,’ said Talmy. ‘He was one of the most innovative guitarists I’ve ever run across. Jimmy Page stole the bowing bit of the guitar from Eddie. Eddie was phenomenal.’

However, Page claims another source for the inspiration. At the Burt Bacharach session he played on, David McCallum, Sr., another session player, who played violin with both the London Philharmonic and Royal Philharmonic orchestras and was father of the co-star of the hit television series The Man from U.N.C.L.E., asked the guitarist if he had tried to bow his instrument as though it were a violin. Page borrowed the violinist’s bow – a wand finding its own wizard – and had a go, in front of McCallum. ‘Whatever squeaks I made sort of intrigued me. I didn’t really start developing the technique for quite some time later, but he was the guy who turned me on to the idea.’

The summer months of 1966 were a pivotal time for much of ‘Swinging London’, as Time magazine had dubbed the city. In May, at the NME Poll Winners’ Concert at Wembley’s Empire Pool, the Beatles played what would prove to be their last ever live show in Britain. However, as far as viewers of the televised broadcast of the NME poll were concerned, the Yardbirds closed the concert. Acting on a perverse whim, Andrew Loog Oldham decided that the Rolling Stones’ segment should not be broadcast. When Beatles manager Brian Epstein learned of this, he also demanded – for anxious reasons of ‘cool’ status – that the Beatles be kept off the TV, thereby depriving viewers of the Beatles’ last scheduled live performance in the UK.

Only a few weeks after Page joined the Yardbirds came the debut performance of an act that would seismically shift the entire music scene. On 29 July 1966 Cream – which Clapton had formed with drummer Ginger Baker and bassist and vocalist Jack Bruce – performed their first ever stage show, at Manchester’s Twisted Wheel, a venue more accustomed to hosting pill-popping Mod all-nighters, itself an indicator of changing times. Within a year Cream would be touring the United States to enormous acclaim, and, in a new twist, long-haired and stoned American audiences would reverently sit cross-legged on ballroom floors as Clapton tore through epic, frequently self-indulgent, guitar solos.

The day after the first Cream gig, on 30 July 1966, England won the football World Cup for the first time, on home soil, and national confidence surged. And by the end of the year another power trio, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, were ferociously tearing up and down the UK’s venues and charts, with their first hit ‘Hey Joe’ and sensational live performances.

Following that Wembley NME date, the Rolling Stones were on something of a hiatus. Anita Pallenberg, Brian Jones’s girlfriend, had bought a flat at 1 Courtfield Road, behind Gloucester Road tube station, and the Rolling Stone had moved in with her. Like several women in this rarefied bohemian milieu, Anita had about her an intriguing high-priestess aspect; she was attracted to the occult and was rarely without a bag containing rolling papers, tarot cards and occasionally the odd bone. Christopher Gibbs, a fashionable Chelsea art and antiques dealer, had insisted to Anita that she must buy the property, which only had one room and a set of stairs leading to a minstrel’s gallery that formed a bedroom of sorts.

Page had been friendly with the Rolling Stones, especially Brian Jones, since he first saw them at Ealing Jazz Club four years earlier. Now, in those first months with the Yardbirds, he was an occasional visitor to the Courtfield Road flat, along with Keith Richards and Tara Browne, the Guinness heir who would be dead by the end of the year, crashing his Lotus Elan after leaving the flat, his death celebrated in the Beatles’ ‘A Day in the Life’. It was at 1 Courtfield Road that Jones and Pallenberg began to regularly ingest LSD, soon introducing Richards to its glimpses of another reality. It is unlikely that Page, who developed a fondness for psychedelic drugs and was no longer confined by the rigidity of session work’s time constraints, did not also enter this arcane coterie.

Through Robert Fraser, a Mayfair art dealer and major player in the Swinging London scene, the trio of Jones, Pallenberg and Richards became friends with the revered independent filmmaker and occultist Kenneth Anger, a disciple of Aleister Crowley. Anger’s very beautiful short movies, marinaded in metaphysical matters, were like visual poems. Anger’s use of pop music to tell the story in his films would prove to be hugely influential. Martin Scorsese would replicate it in his breakthrough film Mean Streets, and Anger used Bobby Vinton’s ‘Blue Velvet’ in his 1963 movie Scorpio Rising, 23 years before David Lynch’s film Blue Velvet. Anger considered Pallenberg to be ‘a witch’ – in turn she claimed that everything she knew about witchcraft had been learned from the filmmaker – and Brian Jones too, and that ‘the occult unit within the Stones was Keith and Anita and Brian’. Keith had been turned on to such matters by Anita, and the pair would soon become lovers. A principal consequence of such out-on-the-edge thinking was the writing and recording of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Sympathy for the Devil’, a song that – as Altamont would suggest – may not have been without its consequences. Page was yet to meet Kenneth Anger. But when he finally did, some years later, it began a relationship also not without penalties.

At the beginning of August 1966 the Yardbirds went into IBC Studios to record a new single, with Simon Napier-Bell at the production helm. Although ‘Happenings Ten Years Time Ago’, as the song was titled, came from the germ of an idea that Page and Keith Relf had come up with, the composing credits for the song would be attributed to all five group members. ‘Happenings Ten Years Time Ago’ would be the most psychedelic of all the Yardbirds’ singles. Like a pointer to the future there were dual lead guitars on the record, Page and Jeff Beck, and so Page once more brought in his friend John Paul Jones to play bass. Beck, who had been suffering from ill health, added his own guitar parts later, along with a piece of spoken-word absurdism based on his experiences in a sexual health clinic. Aside from this whimsy, the lyrics themselves had considerable poignancy, relating to experiences of déjà vu or even of past-life existences – appropriately complex subject matter as the pop-based first half of the 1960s gave way to the rockier second half.

‘It was a compressed pop-art explosion, with a ferocious staccato guitar figure, a massive descending riff and rolling instrumental break and LSD-inspired lyrics that questioned the construction of reality and the nature of time,’ wrote Jon Savage in 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded. But by some it was seen as wilfully clever clogs. Penny Valentine, Disc and Music Echo’s reliable record reviewer, was extremely dismissive: ‘I have had enough of this sort of excuse for music. It is not clever, it is not entertaining, it is not informative. It is boring and pretentious. I am tired of people like the Yardbirds thinking this sort of thing is clever when people like the Spoonful and Beach Boys are putting real thought into their music. And if I hear the word psychedelic mentioned again I will go nuts.’

In fact, in the UK ‘Happenings Ten Years Time Ago’ only stuttered to the edge of the Top 30. As far as Britain was concerned, the Yardbirds were – in the jargon of the time – on their way out.