По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

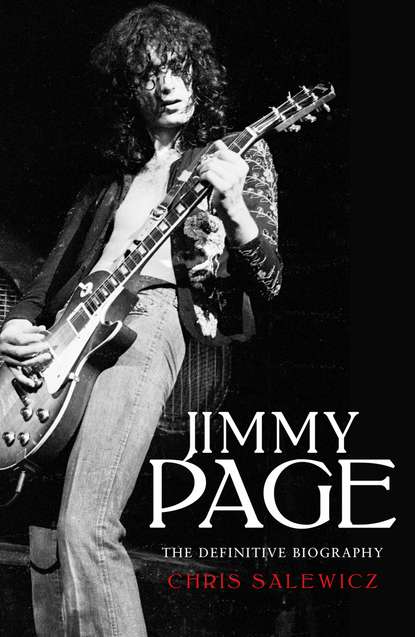

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The tune chosen to acquaint Little Miss Dynamite with the zeitgeist was ‘Is It True’, another song written by Page’s musical allies John Carter and Ken Lewis. The guitarist used an early wah-wah pedal on the record, which hit the same number 17 spot on both sides of the Atlantic.

By now Pete Calvert, Page and Rod Wyatt’s guitar-playing buddy from Epsom, had rented a London flat, 4 Neate House in Pimlico. Page would drop in and sometimes stay over if he had an early gig the next day. Soon Chris Dreja of the Yardbirds moved in to one of the rooms.

A desire to improve upon and expand his natural abilities seemed second nature to Page. Having bought a sitar almost as soon as he learned of the instrument’s existence, he became one of its earliest exponents in the UK. ‘Let’s put it this way,’ he said. ‘I had a sitar before George Harrison. I wouldn’t say I played it as well as he did, though. I think George used it well … I actually went to see a Ravi Shankar concert one time, and to show you how far back this was, there were no young people in the audience at all – just a lot of older people from the Indian embassy. This girl I knew was a friend of his and she took me to see him after the concert. She introduced him to me and I explained that I had a sitar, but did not know how to tune it. He was very nice to me and wrote down the tunings on a piece of paper.’ On 7 May 1966 Melody Maker, the weekly British music paper that considered itself intellectually superior to the rest of the pop press, ran an article entitled ‘How About a Tune on the Old Sitar?’, with much of its information taken from Page.

This questing side of him surfaced again in his efforts to improve his abilities on the acoustic guitar. ‘Most great guitarists are either great on electric or great on acoustic,’ said Alan Callan, who first met Page in 1968 and in 1975 became UK vice president of Swan Song Records, Led Zeppelin’s label. ‘But Jim is equally great on both, because he is always faithful to the nature of the instrument. He told me that, quite early on, he’d gone to a session and the producer had said, “Can you do it on acoustic rather than electric?” And he said he came out of that session thinking he hadn’t nailed it, so he went home and practised acoustic for two months.’

The first half of the 1960s was a boom period for UK folk music, with several emerging virtuosos, revered by young men learning the guitar or – in Page’s case – always eager to improve. John Renbourn, Davey Graham – who incorporated Eastern scales into his guitar playing – and Bert Jansch were the holy triumvirate of these players; Page was especially turned on by Jansch, who introduced him to ‘the alternate guitar tunings and finger-style techniques he made his own in future Zeppelin classics such as “Black Mountain Side” and “Bron-Y-Aur Stomp”,’ according to Brad Tolinski in his book Light and Shade.

‘He was, without a doubt, the one who crystallised so many things,’ Page said. ‘As much as Hendrix had done on the electric, I really think he’s done on the acoustic.’ Al Stewart, a folk guitarist and singer, and, like Jansch, a Glaswegian, explained to Page that Jansch’s guitar was tuned to D-A-G-G-A-D – open tuning, as it was known. Page started to employ this himself.

3

SHE JUST SATISFIES (#ulink_6c1dc1d0-7973-5a9b-9140-50246c76bce4)

While much of Jimmy Page’s work consisted of bread-and-butter pop sessions, from time to time he would be offered the opportunity to indulge his creative side. On the morning of 28 January 1965, for example, half a dozen of Britain’s most accomplished musicians met at IBC Recording Studios at 35 Portland Place in London for the morning session slot. Page was on guitar, Brian Auger on organ, Rick Brown played the bass and Mickey Waller was the drummer, with Joe Harriott and Alan Skidmore on saxophones. They were assembled to record an album with the American blues legend Sonny Boy Williamson. ‘We started at 10 a.m. and it was all done by 1 p.m.,’ recalled Waller. ‘Also, it was done completely live: there were no overdubs. We all sat in a circle and played.’ After Williamson grew progressively more drunk, his skewed sense of timing made the session increasingly difficult.

Page later recalled: ‘Sonny Boy was living in [Yardbirds’ manager] Giorgio Gomelsky’s flat. Somebody told me once that they went to the house and they heard Sonny Boy plucking a live chicken. I don’t know how true that was. That didn’t happen when I was there. Sonny Boy and I rehearsed these numbers in the manager’s flat, and by the time we got into the studio a couple of days later Sonny Boy had forgotten all of the arrangements. It was cool. Good music comes out of that.’ (During Sonny Boy Williamson’s time in Britain, the bluesman performed at Birmingham Town Hall: there, a 16-year-old Robert Plant, stunned almost breathless from watching his performance, didn’t permit his awe to prevent him from sneaking backstage and stealing one of the blues master’s harmonicas – revenge, apparently, for the legendarily acerbic Williamson having told Plant to ‘fuck off’ when the teenager attempted to greet him while standing side by side at a urinal.)

When the Sonny Boy Williamson album session took place, Page had just become involved with another American – one who was blonde and female. Jackie DeShannon, hailing from Kentucky, was a beautiful singer-songwriter and a musical prodigy from an early age. By the time she was 11 she had her own radio show. In her early teens she had become a recording artist, at first singing country music. Her records ‘Buddy’ and ‘Trouble’ came to the attention of the great American early rocker Eddie Cochran. With Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly, Cochran was a rock ’n’ roll singer-songwriter; by a measure of synchronicity he was also a hero of Page – Led Zeppelin would sometimes feature covers of some of Cochran’s greatest songs: ‘C’mon Everybody’, ‘Summertime Blues’, ‘Nervous Breakdown’ (which effectively was what ‘Communication Breakdown’ was) and ‘Somethin’ Else’. ‘You know, you look like a California girl,’ Eddie said to her. ‘I think that you should be in California if you want to have a great career.’

DeShannon moved to Los Angeles, where Cochran was based, and he teamed her up with singer-songwriter Sharon Sheeley, his girlfriend, who wrote ‘Poor Little Fool’ for Ricky Nelson. The two girls started to write songs together, resulting in ‘Dum Dum’, a hit for Brenda Lee, and ‘I Love Anastasia’, which scored for the Fleetwoods. (Along with Gene Vincent, Sharon Sheeley was injured in the car crash in England that took Eddie Cochran’s life on 17 April 1960.)

At the age of 15 DeShannon became a girlfriend of Elvis Presley, which became part of her myth; she also had a relationship with Ricky Nelson. Although she failed to have big chart hits of her own in the United States, her version of Sonny Bono and Jack Nitzsche’s ‘Needles and Pins’ was a number one record in Canada before the Searchers covered it in the UK, where it also topped the charts. The Searchers soon covered DeShannon’s own song ‘When You Walk in the Room’, releasing it in September 1964, when it reached number three in the UK charts. In August and September of 1964 she was also one of the support acts on the Beatles’ first tour of the USA – her backing musicians on those dates included a young Ry Cooder.

Sniffing the cultural wind, as Shel Talmy, Bert Berns and Brenda Lee had done, Jackie DeShannon arrived in the UK to record at the EMI Studios on Abbey Road at the end of 1964. ‘I was very used to working with people like Glen Campbell and James Burton and Tommy Tedesco – all these great, great guitar players,’ she recalled. ‘So when I was there I said, “Who’s an amazing acoustic guitar player that I can have on my sessions?” and they all said that Jimmy Page was the guy, because he had played on a lot of different hit records at the time and was one of the guys on the “A list” of studio musicians to call.

‘So I said, “Great, let’s have him,” and they said, “Well, you can’t get him here because he’s in art school.” I said, “What?” He showed up … with paint on his jeans and he was the youngest player in the room. I went over to him to play a few of my piddling chords, and when he played them back to me I was almost knocked out of the room. Even then, he was spectacular. I knew right then that he was an amazing talent, so he played on a song of mine called “Don’t Turn Your Back on Me” and we did some writing together.’

There was, however, an attraction beyond his guitar-playing skills and Jackie DeShannon’s own musical abilities. ‘We got together afterwards,’ Page said in an interview in 1977 when he revealed how she enticed him with a very attractive proposition: ‘She said, “I’ve got a copy of Bob Dylan’s new album if you’d like to hear it,” and I said, “Would I like to hear it?”’

For most of 1965 Page and Jackie DeShannon were an item, and this almost-eminent American songwriter took him under her wing; together they wrote the song ‘Dream Boy’, a rocking single, like Ronnie Spector handling a surf tune. At the time Marianne Faithfull felt that Page was ‘rather dull’. She saw his relationship with DeShannon as his way of ‘undulling himself’. Tony Calder, her manager and close associate of Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, recalled that ‘One night I couldn’t get into our hotel room because Jimmy and Jackie DeShannon were in there shagging, so I yelled, “When you’ve finished could you write a song for Marianne?”’

The result was Marianne Faithfull’s second hit, ‘Come and Stay with Me’, which reached number four. ‘In My Time of Sorrow’, an album track for Marianne, also emerged from this partnership.

‘We wrote a few songs together, and they ended up getting done by Marianne, P. J. Proby and Esther Phillips or one of those coloured artists … I started receiving royalty statements, which was very unusual for the time, seeing the names of different people who’d covered your songs,’ said Page.

But how must it have felt for Page to be having sex with someone who had been to bed with two of his idols, Elvis Presley and Ricky Nelson? No doubt it considerably boosted his sense of himself and who he could be, given his increasing belief in psychic connections and the powerful, allegedly transcendent energies of Aleister Crowley’s ‘sex magick’.

Page was always financially astute. Early in 1965 he had set up his own publishing company, and soon, urged on creatively and emotionally by Jackie DeShannon, he was making his first solo record. ‘She Just Satisfies’ was a Kinks-style rocker, released on the Fontana label, on which he sang; its B-side was another Page–DeShannon tune, ‘Keep Moving’. Hearing it now, ‘She Just Satisfies’ sounds like it could have been a likely chart contender.

‘“She Just Satisfies” and “Keep Moving” were a joke,’ Page later said, dismissing the record with an element of false modesty. ‘Should anyone hear them now and have a good laugh, the only justification I can offer is that I played all the instruments myself except the drums.’

In his 1965 interview with Beat Instrumental magazine, Page was asked about the possibility of a follow-up to ‘She Just Satisfies’. He rejected the notion saying, ‘If the public didn’t like my first record, I shouldn’t think they’ll want another.’

In March 1965 DeShannon took Page on his first trip to the United States, first to New York and then to Los Angeles. For the guitarist, who later admitted his first impressions of the USA came from the glamour of Chuck Berry’s witty, lyrically descriptive songs, life was suddenly opened up almost unimaginably.

In New York, Page crashed in the spare room of Bert Berns’s sumptuous Manhattan penthouse apartment, with the producer, who was in town, and his Great Dane and pair of Siamese cats. While Page was in the Big Apple, the ever-dynamic Berns produced Barbara Lewis’s ‘Stop That Girl’, a song written by Page and DeShannon; this mid-tempo heartbreak ballad was included on the Michigan soul songstress’s Baby, I’m Yours LP, released on Atlantic that year. Through Berns, Page met Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler, the head honchos of Atlantic Records; it was a connection that would prove exceptionally valuable. Berns also ‘took him to an Atlantic session, where he strummed along uncredited because of the union and immigration’.

Then Page flew to the West Coast. With its warm whisper of fecund possibility, Los Angeles in the mid-1960s seemed like a mythical setting. Almost all knowledge of the city was informed by its portrayal in movies, with Hollywood almost like the Holy Grail. With many of its inhabitants drawn from across the globe by the hope of stardom, LA housed some of the most beautiful individuals, of either sex, that any urban conurbation could boast.

The perfect weather of Los Angeles, its motorised modernity, gorgeous landscapes and fascination with alternative, free-thinking lifestyles – since the 1920s the city had been known for its practitioners of the more arcane, esoteric arts – made for an attractive package.

But its air of affluence could be illusory. In August 1965, when the foreign press went looking for the riots in the south Los Angeles district of Watts, many newshounds famously drove straight through the neighbourhood. Searching for a ‘black ghetto’, they were unable to believe that this place, with its palm trees and neat bungalows, could be the scene of murderous urban discontent.

The Watts riots were in stark contrast to the received wisdom about Los Angeles and southern California in general. But they were also a metaphor for the darkness that lay at its heart, always ready to erupt, like the city’s ever-present threat of earthquake.

It was already apparent that Page had a nose for the zeitgeist, and here he was ahead of the times: for shortly Los Angeles would become the world’s popular-music capital. ‘I first came here in 1965 when I was a studio musician,’ he told the Los Angeles Times in 2014. ‘Bert Berns brought me out. He invited me to stay at his place. I met Jackie DeShannon, I saw the Byrds play at Ciro’s [the Byrds debuted at Ciro’s on 26 March 1965], which I think is now the Comedy Store. It was a magical time to be here. It was really happening.’

One morning he walked into the coffee shop at the Hyatt House on Sunset Boulevard. Seated there, having his breakfast, was Kim Fowley, a veteran of the Hollywood music scene who had been involved with the Hollywood Argyles, B. Bumble and the Stingers, and the Rivingtons; in London, where he had met Page, Fowley had worked with P. J. Proby. ‘In he comes, Mister boyish, dressed in crushed velvet. He spotted me, and came and sat down. He told me he’d just had the most insane, disturbing experience.

‘A well-known singer-songwriter of the time, a pretty blonde, had asked him over to her house. When he got there, she’d detained him. He said she’d used restraints. I asked if he meant handcuffs and he said yes, but also whips – for three days and nights. He said it was scary but also fun. They say there’s always an incident that triggers later behaviour. I contend that this was it for Jimmy Page. Because being in control – that became his deal.’

After a few months this early example of a rock ’n’ roll couple went their separate ways. ‘He wanted to split from the music world because he was getting disillusioned,’ said Jackie DeShannon. ‘Jimmy wanted to go to Cornwall or the Channel Islands and sell pottery. He couldn’t stand the business, the strain, and I couldn’t stand his dream of quietness, so we split, but I guess he’s changed a lot since then.’

The song ‘Tangerine’ on Led Zeppelin III is said to have been inspired by Jackie DeShannon.

In May 1965 Bert Berns was back in London, producing tracks for Them’s first album, this time at Regent Sounds Studio on Denmark Street. Clearly uninfluenced by the protests of Billy Harrison, Berns again brought in Jimmy Page, who provided a ‘vibrato flourish’ on an interpretation of the Josh White folk song ‘I Gave My Love a Diamond’.

Prior to the arrival in October 1962 of the Beatles with ‘Love Me Do’, their first Parlophone single, and their subsequent phenomenon, not just as performers but supreme songwriters, British pop music was dominated by material that traditional ‘Tin Pan Alley’ publishers touted to acts. Despite the Liverpool quartet’s success, which led to so many emergent acts writing their own material, by 1965 the Beatles had by no means overthrown this system. The Yardbirds, a group largely from the extremes of south-west London, were an act that demonstrated the severe disparity between their singles, chosen by such a method, and the material in the five-piece group’s live sets – essentially another version of the harmonica-wailing, thunderously paced and mutated rhythm ’n’ blues sound that the Rolling Stones and Pretty Things and other lesser UK groups like the Downliners Sect were somewhat histrionically howling.

The Yardbirds had formed after Chris Dreja, Anthony ‘Top’ Topham and Eric Clapton met at Surbiton Art College. ‘It was through Top Topham’s father,’ said Chris Dreja, ‘who had this amazing collection of 78s from America [that was] not available to anybody. It was black blues music, and that was the initial turn-on, of course. Discovering that music was like the genie coming out of the bottle, really. We had really rather kitsch pop music with no free fall and very little emotion back in the depressing post-war fifties and sixties.

‘And poor old Anthony Topham gets left out, doesn’t he? He was quite pivotal, actually. The band was made up of two halves originally. One half was Top and me at art college, and Clapton was in the same art stream. In Surbiton, Surrey, of all places.

‘At that stage Top Topham was perhaps as agile and skilled a guitar player as Eric Clapton. He was only 16, however, and his career with the Yardbirds was stymied when his parents insisted that he must remain in full-time education.

‘Topham is still a great guitar player. He went on to play for Chicken Shack. Out of all us he was actually the most talented artist around. Clapton and I were all into music, but he got dropped at Kingston Art School because his attentions were elsewhere. But Top’s parents, when we were getting wages from it, grounded him, unfortunately, and that is when we got Clapton. He was really the only professional player we knew out there who had any background in the music we were doing.’

Keith Relf, the group’s singer, knew Eric Clapton better than the pair of students who were at college with him, so he went and ‘tracked him down’, as Dreja remembered. Clapton had already moved on to Kingston College of Art, but had been dismissed after his first year; it was considered by his instructors that he was focused on music and not on art.

By the end of 1964 the Yardbirds had a blossoming reputation and were considered one of the coolest UK acts, clearly on the cusp of breaking out from being a cult attraction, not least because of their by now revered guitarist. The Yardbirds – who otherwise consisted of flaxen-haired vocalist Keith Relf, second guitarist Chris Dreja, bass player Paul Samwell-Smith and drummer Jim McCarty – were managed by Giorgio Gomelsky, who had had the Rolling Stones stolen from him by Andrew Loog Oldham and Eric Easton.

The song that would pull the Yardbirds up to full pop stardom was ‘For Your Love’. One of the first two tunes written by Manchester’s Graham Gouldman, later of 10cc, ‘For Your Love’ had been intended for his group the Mockingbirds, until they turned it down, as did Herman’s Hermits, who in Harvey Lisberg had the same management as Gouldman. Undaunted by this negative response, Lisberg, who was very impressed by ‘For Your Love’, then offered it to the Beatles when they played a season of Christmas shows at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1964. Unsurprisingly, the Fab Four, who had their own abundant source of material, displayed no interest. But supporting the Beatles on these Hammersmith shows were the Yardbirds, and they recognised its chart potential and recorded it.

A good call: the single, released in March 1965, was a big hit. Yet ‘For Your Love’ was at considerable odds with the rest of the band’s previous material. The Yardbirds had already put out a pair of what might be considered more characteristic tunes: ‘I Wish You Would’, a version of the 1955 Billy Boy Arnold Chicago blues tune; and ‘Good Morning, School Girl’, an adaptation of the 1937 Sonny Boy Williamson song, often titled ‘Good Morning Little Schoolgirl’ – a title that in later years would have guaranteed zero radio airtime. On the live version of ‘Good Morning, School Girl’, on the Yardbirds’ first live album, Five Live Yardbirds, the vocal duties on the song were taken by bass player Paul Samwell-Smith and Eric Clapton rather than singer Keith Relf.

He might have been underestimated in his days at the Ealing Jazz Club, but by now Clapton was showing that he was very much his own man, utterly singular in his purist vision of the kind of music he should be playing: he was determined that the next Yardbirds single should be an Otis Redding cover. His stance, and clear supreme abilities on the guitar, were beginning to transform him into a hero for his fans. And in March 1965 the Melody Maker headline told the story: Clapton Quits Yardbirds – ‘too commercial’.

‘I thought it was a bit silly, really,’ said Clapton of ‘For Your Love’. ‘I thought it would be good for a group like Hedgehoppers Anonymous. It didn’t make any sense in terms of what we were supposed to be playing. I thought, “This is the thin end of the wedge.”’

In the story that accompanied the Melody Maker headline, Keith Relf gave his version of what had taken place. ‘It’s very sad because we are all friends. There is no bad feeling at all, but Eric did not get on well with the business. He does not like commercialisation. He loves the blues so much I suppose he does not like it being played badly by a white shower like us! Eric did not like our new record “For Your Love”. He should have been featured but did not want to sing or anything, and he only did a boogie bit in the middle. His leaving is bound to be a blow to the group’s image at first because Eric was very popular.’

Chris Dreja put the problem more succinctly: ‘We had this massive record and we had no lead guitar player.’

Within two weeks Clapton had joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. After a couple of months graffiti began to appear around London: ‘Clapton is God’. John Mayall, a bohemian Mancunian who rivalled Alexis Korner as the godfather of the UK blues scene, had already offered Page the job with the Bluesbreakers, but he had turned it down, clearing the way for Clapton.

Page was clearly in demand. The Yardbirds and their manager Giorgio Gomelsky, at the suggestion of Eric Clapton himself, first approached Page to be the guitarist’s replacement.