По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

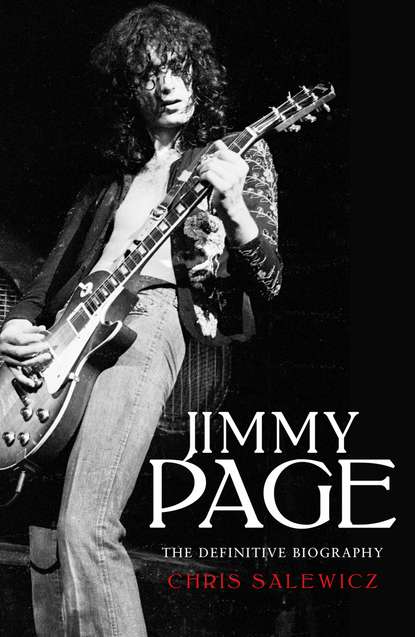

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

To an extent this only child – until he started school at the age of five he hardly knew any other children – was always self-educated, manifesting a strong sense of self-fulfilment, even destiny – though there is often something fixed and inflexible about the self-taught. ‘That early isolation probably had a lot to do with the way I turned out,’ he said later. ‘Isolation doesn’t bother me at all. It gives me a sense of security.’

Heston, his birthplace, has a distinct sense of J. G. Ballard-like suburban anonymity, the net curtains firmly drawn on all manner of potential darkness. Heston lies on the direct flight-path into Heathrow Airport, less than three miles away, and today is a place blighted by the ever-present roaring reverse thrust of descending jet airliners. It was the beginnings of this noise pollution that led the Page family to move first to nearby Feltham, a distance of some four miles, where unfortunately the noise from aeroplanes was even more acute, and then the ten miles or so to the south-east, to 34 Miles Road in Epsom, Surrey, in 1952. (In 1965 Page would, with Eric Clapton, record a song entitled ‘Miles Road’.)

Eight-year-old Jimmy Page was enrolled at Epsom County Pound Lane Primary School, and at the age of eleven he moved on to Ewell County Secondary School, on Danetree Road in adjacent West Ewell. His headmaster, Len Bradbury, who took over in 1958 when Page was in year three, had played football for Manchester United, and Bradbury’s arrival at the school was only a few months after his former team had been decimated in the Munich air disaster. (Many years later Bradbury would be a guest of honour at Manchester United’s ground, with pictures of him taken with the team’s captain, Roy Keane, and Ryan Giggs.) Page was in the proximity of celebrity – and he could see that such individuals were sort of ordinary people.

At 34 Miles Road, Page discovered a Spanish guitar that had been left behind, presumably by the previous occupiers. Had it ever been played? Perhaps not. In the 1950s a Spanish guitar as an objet d’art in the home was considered a sign of sophistication. ‘Nobody seemed to know why it was there,’ he told the Sunday Times. ‘It was sitting around our living room for weeks and weeks. I wasn’t interested. Then I heard a couple of records that really turned me on, the main one being Elvis’s “Baby Let’s Play House”, and I wanted to play it. I wanted to know what it was all about. This other guy at school showed me a few chords and I just went on from there.’

‘This other guy’ was called Rod Wyatt. Although fascinated by the Spanish guitar, Page all the same had been flummoxed by how to play the instrument. During a lunch break at secondary school, he came across Wyatt, who was in a class a couple of years above him. The owner of an acoustic guitar of his own, Wyatt was running through a version of ‘Rock Island Line’, a chart hit by the revered Lonnie Donegan, when he met Page. In response to the younger boy’s query, Wyatt instructed him to bring his Spanish acoustic to school and he would show him how to tune the instrument. From then on the pair became firm friends.

‘My mate Pete Calvert and I were always at Jimmy’s house bashing out our guitars for a couple of hours on a Saturday afternoon,’ said Wyatt. ‘Sometimes I’d go round to Jimmy’s and his mum would say, “No, he’s practising.” When he suddenly realised he had it, he spent a lot of time practising. Sometimes six or seven hours a day. He told me he needed to improve his technique. And he eventually became the all-round perfect guitarist. Practice is what it’s all about.’

What had really turned Page on in Elvis Presley’s rockabilly song ‘Baby Let’s Play House’, released in the UK six days before Christmas 1955, was the guitar playing of Scotty Moore, who served as Presley’s guitarist from 1954 to 1958. On 5 July 1954 Moore had, with bassist Bill Black and Elvis himself, mutated the original arrangement of ‘That’s All Right’ by bluesman Arthur Crudup into a version that combined blues and country music, creating one of the foundations of rock ’n’ roll.

‘Scotty Moore had been a major inspiration in my early transitory days from acoustic to electric guitar. His character guitar playing on those early Elvis Sun recordings, and later at RCA, was monumental. It was during the fifties that these types of song-shaping guitar parts helped me see the importance of the electric guitar approach to music,’ said Page.

On ‘Baby Let’s Play House’ Moore played a burnished rockabilly rhythm. Page’s love of the tune would not leave him, even after almost 20 years: about nine minutes into the live version of ‘Whole Lotta Love’ in the Led Zeppelin film The Song Remains the Same he breaks into a close simulacrum of Moore’s licks. But that was a long way in the future: for now the 12-year-old Page assiduously studied and copied Moore’s parts. There could hardly be a purer, more perfect example of this brand new musical form, an ideal introduction to what his life would become. Every day he would take his guitar to school on Danetree Road.

‘When I grew up there weren’t many other guitarists,’ he told America’s National Public Radio in 2003. ‘There was one other guitarist in my school who actually showed me the first chords that I learned and I went on from there. I was bored so I taught myself the guitar from listening to records. So obviously it was a very personal thing.’

But he also had a seemingly separate life as a choirboy. Each Sunday, wearing the appropriate surplice and cassock, he would sing hymns at Epsom’s St Barnabas Anglican Church. The first image in his 2010 photographic autobiography is of him in this mode – clearly he is being ironic. As so often in the life of Jimmy Page, cold realism lay behind the impetus for his choirboy stints.

‘In those days it was difficult to access rock ’n’ roll music,’ he said to the Sunday Times in 2010, ‘because after all the riots happened in the cinemas, when people heard “Rock Around the Clock” in the film Blackboard Jungle, the authorities tried to lock it all down. So you needed to tune in to the radio or go to places where you could hear it. It just so happened that in youth clubs they would play records and you’d get to hear Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis and Ricky Nelson – but you had to either go to church or be a member of the choir to go to the youth club.’

Page had many of the characteristics of the only child, burying himself in books and, almost the ultimate cliché, collecting overseas postage stamps. But more and more since discovering that Spanish guitar at Miles Road, he immersed himself in becoming adept on the instrument. ‘The choirmaster at St Barnabas remembered that I used to take my guitar to choir practice,’ he said, ‘and ask if I could tune it up to the organ.’

In Epsom there is a prominent motorcar showroom named Page Motors. It has often been claimed, even by myself, that this business is owned by members of Page’s family. But this is not the case at all. His relatives on his father’s side came from Grimsbury in Northamptonshire, and his paternal grandfather had been a nurseryman, tending to plants. (An irony that would not be lost on Page, who later had a Plant of his own to deal with, of course.) On his father’s side there was Irish blood.

At 122 Miles Road, at the far end of the street from the Page family home at number 34, lived a boy of similar age to Page called David Williams. According to Williams, Miles Road, which lay to the west of Epsom, was distinctly the wrong side of the high street. To the east lay the plush property in which affluent commuters to London were ensconced. The Page house backed onto the railway line that transported these people to the capital, less than 20 miles away, and was identical to the Williams home, having a downstairs living room and dining room and a pair of bedrooms upstairs. Downstairs, beyond the kitchen, was an outside toilet. Although most of these houses, including the Pages’, later had this feature adapted into a full bathroom, there is no getting away from the fact that these were distinctly basic homes.

Page’s father worked in nearby Chessington, a personnel manager at a plastic-coating factory, and his mother was the secretary at a local doctor’s practice. Despite the impeccable ‘BBC English’ – as such received pronunciation was known at the time – with which rock star Jimmy Page would express himself, his background was no more than lower middle-class, almost jumped-up working-class.

Another good friend, Peter Neal, lived on Miles Road. Page, Peter Neal and David Williams would hang out at each other’s houses. Gradually Page’s home – without any brothers or sisters to get in the way – became a focal point. He also had the advantage of enjoying both parents – although Wyatt mentions some growing tension between his mother and father. When Williams was just 13, his own mother had died: ‘I am certain that Jim’s mother was the initial driving force behind his musical progression. She was a petite, dark-haired woman with a strong personality, a glint in her eye and wicked sense of humour. She liked to tease me in a good-natured way, but let me hang out endlessly in their front room with Jim. I think she must have known my mother and, given the new circumstances I found myself in, I guess she felt sorry for me. Although I didn’t realise it at the time, I can now appreciate her kindness and tolerance, for I must have been a fairly constant presence in her house.’

After hearing Chuck Berry, the black poet of rock ’n’ roll sensibility, on American Forces Network radio broadcasting fuzzily from Germany in 1956, Williams acquired a UK EP that gathered together the songs ‘Maybellene’, ‘Thirty Days (To Come Back Home)’, ‘Wee Wee Hours’ and ‘Together (We Will Always Be)’. He and Page played it incessantly, the latter being especially taken with ‘Maybellene’ and its tale of amorous automobile class struggle, and with ‘Thirty Days’.

From the equipment Page quickly began to amass, it seems that this only child was a little spoilt – or, at least, certainly lucky. He was the first of his friends to acquire a reel-to-reel tape recorder, which he soon replaced with a newer model, selling the older one to Williams so he could then pass on the tapes of songs he would diligently record off the radio.

Discerning in their taste, certainly to their own minds, these boys truly cared for only a handful of artists: Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis – the eccentric and wild Jerry Lee, with his 13-year-old bride, being Page’s especial preference. Eddie Cochran would soon emerge to join this pantheon.

They would visit and revisit their local cinemas to watch such films as The Girl Can’t Help It, a minor triumph in 1956 that featured Little Richard, Fats Domino, Eddie Cochran, Julie London and the Platters. Also released that year was the more pedestrian Rock, Rock, Rock!, which had a highlight performance of ‘You Can’t Catch Me’ by Chuck Berry, his patent-leather pompadour and sneering grin permanently lending him the appearance of one of those black pimps whose look Elvis Presley had tried so hard to emulate. One Saturday afternoon in 1960 Page and Williams would hitchhike 50 miles to Bognor Regis to catch Berry performing a solitary tune in the classic film Jazz on a Summer’s Day.

In the record department of Rogers, an electrical goods shop on Epsom High Street, the three boys ingratiated themselves with the girl behind the counter. This ally would provide them with glimpses of record-company schedules of forthcoming releases. The boys would search out the most interesting names. ‘Frankie Avalon and Bobby Rydell were clearly to be overlooked in favour of the likes of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins or Big “T” Tyler,’ recalled Williams. ‘Also, song titles could often be a good indication of something a little stronger. The dreaded “A White Sport Coat (and a Pink Carnation)” was hardly going to evoke the sort of enthusiasm and anticipation we would have for titles such as “Rumble”, “I Put a Spell on You” or “Voodoo Voodoo”, was it?’

Soon appreciating the limitations of his Spanish acoustic instrument, Page worked for some weeks during the school summer holidays on a milk round, until he had saved up enough money to buy a Höfner President acoustic guitar. ‘It was a hollow-bodied acoustic model with a simple pickup,’ said Williams, ‘but when he attached it to a very small amplifier, it made something like the sound we all admired. I can recall that Saturday morning when I was summoned to his house to first feast eyes on it. Jim was like the cat with the cream. Pete and I were allowed a strum, but by now we realised that any aspirations we might have had in that direction were going to be dwarfed by Jim’s talent, desire and progress.’

After Page had acquired his Höfner President, his parents paid for lessons from a guitar tutor. But the teenager, anxious to play the hits of the day, found himself mired in learning to sight-read; soon he abandoned the lessons, preferring to attempt to learn to play by ear. Later he would appreciate that his impatience had been an error, finally picking up the skill of reading music in the mid-1960s.

‘Rock Island Line’, the tune that Wyatt had been playing when Page approached him, was a Top 10 hit in 1956 for Lonnie Donegan on both sides of the Atlantic – in the UK alone the record sold over a million copies. The song was an interpretation of the great bluesman Leadbelly’s own version, and it became the flagship for skiffle music.

Skiffle, a peculiarly British grassroots companion movement to rock ’n’ roll that required no expensive equipment, was played on guitars but also on homemade and ‘found’ instruments. Donegan, a member of Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen, would play with a guitar, washboard and tea-chest bass during intervals at Colyer’s traditional jazz sets. In 1957 the BBC launched its first ‘youth’ programme, Six-Five Special, with a skiffle title song. The craze swept Britain at an astonishing rate: it was estimated that in the UK there was a minimum of 30,000 youngsters – maybe almost twice that – playing the musical form. Across the country groups were created: John Lennon’s Quarrymen were a skiffle group that would lead to the formation of the Beatles.

In accord with this spirit of the age, Page formed such a skiffle group, which his parents permitted to rehearse in their home. Really, this ‘group’ was little more than a set of likeminded friends, sharing their small amounts of knowledge about this new upstart form. Yet they seemed bestowed with a measure of blessing: in 1957, with Page just 13 years old, the James Page Skiffle Group, following an initial audition, won a spot on an early Sunday evening children’s BBC television show, All Your Own, hosted by Huw Wheldon, a 41-year-old rising star (11 years later Wheldon would become director of BBC television). The slot in which they were to be featured was one hinged around ‘unusual hobbies’. How did they get this television slot? By chance, runs part of their appearance’s myth: the show was looking for a skiffle act, and someone working on it was from Epsom and had heard of Page’s band. But there is also a suggestion that Page’s ever-supportive mother wrote a letter to the programme, suggesting her son’s group.

Unfortunately, the membership of the James Page Skiffle Group has largely been lost in time. For the television appearance, a boy named David Hassall, or perhaps Housego, was involved. Not only did his family own a car, but his father possessed a full set of drums, which David endeavoured to play.

On a day during the school holidays when the show was to be recorded, Page and Williams caught a train up to London to the BBC studio. Page’s mother had phoned William’s father to ask if his son would accompany him to the recording. ‘The electric guitar itself was already heavy enough for him to carry, but the amplifier was like a little lead box and he clearly could not carry both.’

At around 4 p.m. Huw Wheldon appeared, fresh from a boozy media lunch, and asked: ‘Where are these fucking kids then?’

His hair Brylcreemed into a rock ’n’ roller’s quiff and his shirt collar crisply fitted in the crew-neck of his sweater, Page – his Höfner President guitar almost bigger than himself – led his musical cohorts through a pair of songs, ‘Mama Don’t Want to Skiffle Anymore’ and ‘In Them Old Cottonfields Back Home’. (Page had also prepared an adaptation of Bill Doggett’s ‘Honky Tonk’, but he was – rightly – doubtful he would get to play it, as he felt certain they would need him to sing.) After the performance, he was interviewed by Wheldon, and, with an irony now all too evident, Page declared to the avuncular presenter that his intention was to make his career in the field of ‘biological research’, modestly declaring himself not sufficiently intelligent to become a doctor. His ‘biological research’ remark certainly was not glib; Page wanted, he told Wheldon, to find a cure for ‘cancer, if it isn’t discovered by then’. Clearly this was a serious, thoughtful young man.

You can only imagine the confidence that this TV appearance must have engendered in the boy who had just become a teenager: in 1957 no one knew anyone who had appeared on the magical new medium of television.

Having been watched by an audience of hundreds of thousands at the age of 13, why not carry on as he had begun? Success might not have been instant, but within four years Jimmy Page would become a professional musician.

In the meantime, BBC television had finally begun to give limited exposure to rock ’n’ roll, and Buddy Holly appeared on its solitary television channel. ‘When he was killed in a plane crash in 1959,’ said David Williams, ‘I recall that Pete, Jim and I put on black ties and went to the local paper shop to buy all the newspapers that carried photos and obituaries of one of our heroes.’

In his woodwork class Page carved a reasonable simulacrum of a Fender Jazz Bass, modelling it on the instrument used by Jerry Lee Lewis’s bassist in the film Disc Jockey Jamboree. ‘It sounded good enough,’ said Williams.

‘To say Jim was dedicated would be an understatement. I hardly ever saw him when he wasn’t strapped to his guitar trying to figure out some new licks.’ Williams noted that Page’s principal inspiration was no longer Elvis Presley or the anguished Gene Vincent, but the ostensibly more wholesome Ricky Nelson. This should not be a surprise: Nelson’s upbeat rockabilly tunes featured the acclaimed James Burton on guitar, as much an inspiration to Page as Scotty Moore. Ten years later Burton would be leader of Elvis Presley’s TCB band, playing with the King until Elvis’s death in 1977.

‘Those old Nelson records might seem pretty tame now, but back then the guitar solos (including the ones played by Joe Maphis) were cutting-edge stuff and greatly impressed my pal,’ said Williams. ‘I remember that he struggled for a long time with the instrumental break of “It’s Late”, but eventually someone showed him the fingerings he was after and he happily moved on.’

Now Page set about forming a group that played more than skiffle. He found a boy who played rhythm guitar – though with little of the feel of rock ’n’ roll – in nearby Banstead, and then he found a pianist.

Although lacking either a drummer or a name, the trio were, after a number of practice sessions, deemed sufficiently ready by Page to play their first show at the Comrades Club, a drinking establishment for war veterans in Epsom town centre.

The gig was not a colossal success. In fact, Williams said it was ‘a complete shambles’. Certainly, it didn’t help that the three musicians lacked a drummer to propel the tempo; later in his career Page would ensure he played with the very best drummer he could find.

‘As rock ’n’ roll progressed,’ said Wyatt, ‘Jimmy and I added pickups to our guitars; we were going electric. Pete Calvert, a left-handed guitarist and friend of Jimmy’s and mine, had a small early Watkins amplifier and I had a Selmer. Jimmy had a bigger Selmer, a sign of what was to come? All three of us were always around each other’s houses banging rock ’n’ roll. Tommy Steele was making headlines as Britain’s first rock ’n’ roller, and although that was cool we preferred the grittier sound of the American artists such as Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps and, of course, Elvis. And for Jimmy and me, the sound made by Gene Vincent’s lead guitarist, Cliff Gallup: that was the style and guitar sound we loved the best in those days.’

Page knew something had to change. At an electronics trade fair at London’s Earls Court Exhibition Centre, he watched a young schoolboy called Laurie London stand up to sing on one of the stands. (Soon London would be at the top of the charts, in both the UK and USA, with his interpretation of the gospel song ‘He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands’.) Page noticed that the guitarist in London’s backing group was playing a Fender Telecaster, the solid-body guitar he truly coveted that he had seen Buddy Holly playing on television. After the performance, Page spoke with London’s guitarist, took the Telecaster in his hands and played ‘Go Go Go (Down The Line)’, a Roy Orbison tune covered by Ricky Nelson, with Page’s idol James Burton on the guitar parts.

Fender Telecasters, made in the United States, were extremely pricey. Far more affordable, and on sale in London’s musical-instrument shops, was the Futurama Grazioso, a Fender copy replete with tremolo arm, manufactured in Czechoslovakia. Page acquired a second-hand version of this instrument.

Concert venues across the United Kingdom were responding to the new youth market for rock ’n’ roll. By 1958 Epsom’s Ebbisham Hall, little more than a church-hall-type building, had been renamed the ‘Contemporary Club’ for the rock ’n’ roll events it put on each Friday night.

But with another group with whom he briefly played, Page would not even get as far as the Contemporary Club. At around the age of 14, Page briefly became a member of a fledgling local act called Malcolm Austin and the Whirlwinds. On lead vocals was the aforementioned Austin. Tony Busson played bass; Stuart Cockett was on rhythm guitar; there was a drummer named Tom whose surname has evaporated with time; and ‘James Page’, as he was billed, played lead guitar. It was Wyatt who had introduced the various musicians to each other. In 1958 Malcolm Austin and the Whirlwinds played at Busson’s school Christmas concert, a set largely consisting of covers of Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis tunes; they played no more than another couple of dates.

Busson, who was two years older than the group’s guitarist, said that ‘James’ Page was ‘very trendy: Italian jackets and Italian shoes – very pointed. Very cool in his tight jeans and trousers, but very baby-faced. We would go round to his house with our acoustic guitars and listen to his 45s and albums. His mum was always very receptive. She’d give us soft drinks. All we really talked about were guitars and pop music. When I first met Jimmy he only had a semi-acoustic Höfner. Then he got a solid electric, a Futurama Grazioso. He was a great fan of Gene Vincent and the Bluecaps, and also of Scotty Moore. I think he liked anything that was a bit complicated and a bit different.’

The guitarist’s home, remembered Busson, was ‘very lower middle-class.’ But Page struck him as ‘very arty: I thought if he didn’t have a career as a musician he’d be an artist. He left school at 15. I thought he would make it. But I also wondered, “How are you going to support yourself in the interim?”’ Soon Busson would receive an answer.

For Epsom also had larger venues in which more prestigious acts would perform. Wyatt recalled the buzz when a genuine professional rock ’n’ roll show came to Epsom – creating an atmosphere like that of a circus or fair arriving in town. The concert was held at the local swimming baths. ‘Top of the bill,’ said Wyatt, ‘was a singer, one Danny Storm, whose claim to fame was being Cliff Richard’s double. He was a dead ringer. The second headliner was the Buddy Britten Trio. Buddy was a Buddy Holly lookalike. Both Jimmy and I went along to the show, which was very exciting at the time. Halfway through, the compère announced an open-mike talent show; Jimmy and I entered. We both got to play a guitar. I did “Mean Woman Blues” and Jimmy did an instrumental, either “Peter Gunn” or “Guitar Boogie Shuffle”.’

Undaunted by the experience of his show at the Comrades Club, Page had persevered and found a drummer and come up with a name: the Paramounts. And at the end of the summer of 1959 he had a show booked for the Paramounts at the Contemporary Club, supporting Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps, a London group modelled largely on the act, antics and material of Gene Vincent and His Bluecaps.

Although the Paramounts even had a vocalist of sorts, their material that night largely consisted – in the manner of the time – of an instrumental set; Page’s strident guitar playing on Johnny and the Hurricanes’ recent hit ‘Red River Rock’ was notable, impressing Red E. Lewis. Lewis informed his group’s manager, one Chris Tidmarsh, of this guitarist’s prowess: at the end of the Red E. Lewis and the Red Caps’ set, Page came out onstage, borrowed the solid-body guitar of Red Caps guitarist Bobby Oats and played a few guitar parts, including some Chuck Berry solos.