По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

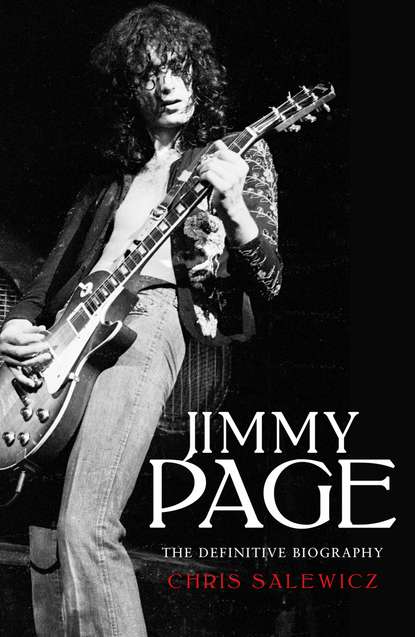

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

From the rear of the hall Page was watched by his parents. Did they believe he would grow out of this silly interest? He told me: ‘No. Actually they were very encouraging. They may not have understood a lot of what I was doing, but nevertheless they had enough confidence that I knew what I was doing: that I wasn’t just a nut or something …’

Also watching the Paramounts that night, from nearer the stage than his parents, was Sally Anne Upwood, Page’s girlfriend at school, a relationship that lasted for a couple of years. Older than her boyfriend, Sally Anne was in Wyatt’s class and able to observe Page’s musical development.

Jimmy Page and the Paramounts played further shows at the Contemporary Club; they supported such acts as the Freddie Heath Combo, who would later be known as Johnny Kidd & the Pirates, one of the greatest English rock ’n’ roll groups. And when Bobby Oats left Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps at Easter 1959, Chris Tidmarsh invited 15-year-old Page to audition, above a pub in Shoreditch, East London. He got the gig, at £20 a week.

Clearly Page’s life was expanding – philosophically, as well as musically. ‘My interest in the occult started when I was about 15,’ he told me in 1977. At this time in his life, when still at school, he read Aleister Crowley’s Magick in Theory and Practice, a lengthy treatise on Crowley’s system of Western occult practice; not an easy book to first comprehend, and a clear indication of the full extent of Page’s precocious intelligence. The book struck into his core, and he said to himself, ‘Yes, that’s it. My thing: I’ve found it.’ From that age he was on his course.

2

FROM NELSON STORM TO SESSION PLAYER (#u9f42648e-3e1c-5cb0-9932-1087e0f7fd79)

At first Jimmy Page could only play with Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps at weekends; he was, after all, still at school.

In fact, at first his father had nixed the idea of his playing with the group. Chris Tidmarsh had needed to come down to 34 Miles Road to see him; it was only when he explained that almost all of the Redcaps’ dates were at the weekend and would hardly interfere with his son’s schooling that Jimmy’s dad agreed. ‘Oh, okay then,’ said the elder James Page.

Yet soon Page had a major contretemps with Miss Nicholson, the deputy headmistress. When he informed her that he intended to be a pop star when he left school, this martinet was utterly dismissive of him. The minimum school-leaving age was 15 at the time, so he walked out of the school with his four GCE O levels and never looked back.

‘Jimmy’s playing was constantly evolving,’ recalled Rod Wyatt. ‘After he left school he could play lead and pick like Chet Atkins; he was a real prodigy. We still jammed at each other’s houses, but not so frequently. The thing about Jimmy was that, unlike most guitarists of those early days, he could play many styles and genres of music.’

Chris Farlowe and the Thunderbirds were an emerging act on the R&B circuit in 1960. Page had first seen Farlowe perform three years before, at the British Skiffle Group Championship at Tottenham Royal in north London.

Farlowe’s throaty soul vocals fronted the outfit, but it was his guitarist Bobby Taylor who Page would assiduously study. ‘He would sit there and watch Bobby playing. Then he’d come backstage and say, “Oh man, what a great guitar player you are.” So Bobby influenced him a great deal,’ Farlowe told writer Chris Welch. ‘Jimmy was very keen to meet him as he thought he was the coolest guitarist he’d ever seen. Bobby Taylor was a very handsome bloke and always dressed in black … Jimmy used to come to our gigs at places like the Flamingo. Then one day he walked up to us at some hall in Epsom, where he lived, and said, “I’d like to finance an album of you and the band.”’

Clearly the 16-year-old Page, who was the same age as Farlowe, had a lucid eye on his future, as he had saved the money, aware that this creative investment would eventually repay him handsomely. And he also declared that he would be the producer of this album, a pronouncement of almost shocking confidence and self-possession from one so young.

The album was recorded at R. G. Jones Studios in Morden, Surrey. Page, observed Farlowe, seemed thoroughly au fait with the workings of a recording studio: ‘He knew what to do and just plugged the guitar directly into the system without using any amplifiers. He didn’t play any guitar himself. He didn’t want to, not with Bobby Taylor playing in the studio.’

The songs included a powerhouse version of Carl Perkins’s ‘Matchbox’ and a hard rendition of Barrett Strong’s ‘Money’, driven by a thundering Bo Diddley beat. But the LP would not be released until 2017, on Page’s own label.

Not content with working his way to becoming the greatest rock guitarist, Page’s intuition had clearly told him to study the art of record production too. Did he have a glimmer that he would bring all this together in the not-too-distant future?

In 1960 Red E. Lewis and the Red Caps were introduced to the beat poet Royston Ellis, who was looking for musicians to back him at a series of readings.

Ellis was born in 1941, three years before Jimmy Page, in Pinner, north-west London, an outer suburb, like Heston in far west London, where Page first lived. Leaving school at 16, he was determined to become a writer, and at the age of 18 he had his first book published, Jiving to Gyp, a collection of his poetry. Ellis was immediately taken with rock ’n’ roll; he would supplement his meagre earnings from poetry by writing biographies of the likes of Cliff Richard and the Shadows and James Dean. In 1961 he published his account of UK pop music, The Big Beat Scene.

Ellis referred to his live events, mixing beat music and poetry, as ‘Rocketry’. At first he had been supported by Cliff Richards’s backing group, the Drifters, who, upon changing their name to the Shadows to avoid confusion with the American R&B vocal group, almost immediately had a number one hit with ‘Apache’ and could no longer fulfil this function for the poet.

Determinedly bisexual and looking for someone to pick up, in 1960 Ellis had encountered George Harrison in the Jacaranda coffee bar in Liverpool. Although Harrison managed to avoid the poet’s advances, the Beetles – as they were then known – ended up backing his poetry reading in the city. Ellis always claimed it was he who suggested they substitute the second ‘e’ in their name for an ‘a’. Lennon later said he saw Ellis as ‘the converging point of rock ’n’ roll and literature’; the song ‘Paperback Writer’ was said to have been inspired by him.

Through Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps, Ellis had learned of the stimulant effects of chewing the Benzedrine-covered cardboard strip inside a Vick’s inhaler, useful for the increasing array of late-night shows the group needed to play in far-flung parts of Britain. The poet turned the Beatles on to this, staying up talking to them until nine o’clock the next morning.

When it came to his backing music, Ellis decided he did not require the entire musical combo of Red E. Lewis and the Red Caps. Instead he settled on only one musician: Jimmy Page.

Between late 1960 and July 1961 Page played several stints backing Ellis. One of the most significant dates they played was a television broadcast, on ITV’s Southern Television, recorded in Southampton with Julian Pettifer. Ellis would later claim that he had secured Page his first TV appearance, though this was manifestly not the case.

Page was still playing his second-hand Futurama Grazioso; soon it would be replaced with a genuine Fender Telecaster. On 4 March 1961 he and Ellis played together at Cambridge University, at the Heretics Society. And on 23 July 1961, having played in assorted coffee bars and small halls, the pair were faced with a bigger challenge. Twenty-year-old Ellis, accompanied by seventeen-year-old Page, was part of the Mermaid Festival at the newly opened experimental Mermaid Theatre, by London’s Blackfriars Bridge. Such illustrious names as Louis MacNeice, Ralph Richardson, Flora Robson and William Empson were also giving readings at the festival.

‘Jimmy Page was very dedicated to my poetry, understood it, and we worked well together, producing a dramatic presentation that was well received both on TV and stage,’ said Ellis.

‘Jimmy composed his own music to back my poems – usually ones from Jiving to Gyp, although I might have been performing the one with the line “Easy, easy, break me in easy” from my subsequent book Rave. The Mermaid show was the peak – and possibly the final one – of our stage performances.’

‘Royston had a particularly powerful impact on me,’ said the musician of the poet’s work. ‘It was nothing like I had ever read before and it conjured the essence and energy of its time. He had the same spirit and openness that the beat poets in America had.

‘When I was offered the chance to back Royston I jumped at the opportunity, particularly when we appeared at the Mermaid Theatre in London in 1961. It was truly remarkable how we were breaking new ground with each reading.

‘We knew that American jazz musicians had been backing poets during their readings. Jack Kerouac was using piano to accompany his readings, Lawrence Ferlinghetti teamed with Stan Getz to bring poetry and jazz together.’

These arty events with Royston Ellis were, however, rare and unusual for Page. More commonly he simply toured incessantly with Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps – and then Neil Christian and the Crusaders.

Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps’ manager Chris Tidmarsh had decided that he would become the group’s singer, renaming himself Neil Christian. In accordance with his own change of identity, Tidmarsh/Christian gave the group the moniker the Crusaders, and Page became ‘Nelson Storm’. Rhythm guitarist John Spicer was henceforth known as ‘Jumbo’, while drummer Jim Evans was given the sobriquet of ‘Tornado’.

Playing the same circuit, with Screaming Lord Sutch and the Savages, was a guitarist who had also grown up in Heston. His name was Ritchie Blackmore, and he had a bright future as a founding member of Deep Purple and celebrated guitar hero in his own right.

‘I met Jimmy Page in 1962. I was 16, 17,’ he recalled of their first meeting, at a time when ‘Nelson Storm’ had acquired a new instrument. ‘We played with Neil Christian and the Crusaders. Jimmy Page was playing his Gretsch guitar. I knew he was going to be somebody then. Not only was he a good guitar player, he had that star quality. There was something about him. He was very poised and confident. So I thought, “He’s going to go somewhere, that guy – he knows what he’s doing.” But he was way ahead of most guitar players. He knew he was good too. He was the type of guy, who … he wasn’t arrogant, but he was very comfortable within himself.’

After two years of life on the road, Page came down several times with glandular fever, a lingering virus that was a consequence of exhaustion and a bad diet – and possibly too regular an ingestion of the Vick’s Benzedrine strip. In October 1962, when he was only 18, ‘Nelson Storm’ quit the Neil Christian outfit.

Almost immediately he enrolled at Sutton Art College in Surrey to study painting, a love almost as great as the guitar. Needless to say, Page’s love of music was undimmed, and he had extremely broad taste, eagerly lapping up classical music, both old and new, especially the groundbreaking work of Krzysztof Penderecki, the Polish composer whose 1960 work Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima conveyed the devastation wrought on 6 August 1945 on the Japanese city. Page’s study of Penderecki’s work would be reflected much later in his use of the violin bow on his guitar.

‘I was travelling around all the time in a bus,’ he told Cameron Crowe in Rolling Stone in 1975. ‘I did that for two years after I left school, to the point where I was starting to get really good bread. But I was getting ill. So I went back to art college. And that was a total change in direction … As dedicated as I was to playing the guitar, I knew doing it that way was doing me in forever. Every two months I had glandular fever. So for the next eighteen months I was living on ten dollars a week and getting my strength up. But I was still playing.’

Only days after Jimmy Page left Neil Christian and the Crusaders he experienced something of an epiphany. For the very first time a package tour of American blues artists was scheduled to play in the United Kingdom. Following concerts in Germany, Switzerland, Austria and France, the American Folk Blues Festival had a date scheduled on 22 October 1962 at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, with both afternoon and evening performances. On the bill were Memphis Slim, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Helen Humes, Shakey Jake Harris, T-Bone Walker and John Lee Hooker.

Page arranged to go with his friend David Williams, but opted to catch the train and meet him in Manchester rather than travel together by road. By now he seemed to have registered that one of the causes of his ill health had been squeezing into an uncomfortable van to travel those long distances across Britain with the Crusaders.

David Williams travelled with a trio of companions he had met at Alexis Korner’s Ealing Jazz Club, in reality no more than a room in a basement off Ealing Broadway in West London. Fellow aficionados of this music, these companions had recently formed a group. Its name? The Rolling Stones. These new friends were called Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones.

Although the first set of the American Folk Blues Festival rather failed to fire, perhaps an expression of the wet Manchester afternoon that it was, the evening house more than lived up to their expectations. Especially when John Lee Hooker closed the show with a brief, three-song set, accompanied only by his guitar. ‘It may have been a damp and grey Manchester outside, but we thought we were sweltering down on the Delta,’ said Williams. Hooker had been preceded by T-Bone Walker, the ‘absolute personification of cool’, according to Williams. ‘He performed his famous “Stormy Monday” on his light-coloured Gibson. His playing seemed effortless, and his set just got better and better as he dropped the guitar between his legs and then swung it up behind his head for a solo. I did not look at Jim, Keith or any of the others while this was all going on, but I can tell you that afterwards they were full of praise and mightily impressed.’

Page, Jagger, Richards, Jones and Williams then drove back to London through the night, Jones nervous about the rate of knots at which they were travelling. In 1962 the M1, Britain’s only motorway, extended no further from London than to the outskirts of Birmingham, a hundred miles north of the capital. ‘Eventually we made it to the motorway and came across an all-night service station. Again, for most of us this was a real novelty. However, Jim was a seasoned night-traveller by now and he clearly enjoyed talking me through the delights of the fry-up menu. After a feed we resumed our journey, and it was still dark when we reached the outskirts of London.’

Early on in his time at Sutton Art College, Page encountered a fellow student called Annetta Beck. Annetta had a younger brother called Jeff, who had recently quit his own course at Wimbledon Art College for a job spray-painting cars. Hot-rod-type motors would become an obsession for Beck.

In a 1985 radio interview on California’s KMET, Beck told host Cynthia Foxx: ‘My older sister, as I remember it, came home raving about this guy who played electric guitar. I mean she was always the first to say, “Shut that racket up! Stop playing that horrible noise!” And then when she went to art school the whole thing changed. The recognition of somebody else doing the same thing must have changed her mind. She comes home screaming back into the house saying, “I know a guy who does what you do.” And I was really interested because I thought I was the only mad person around. But she told me where this guy lived and said that it was okay to go around and visit. And to see someone else with these strange-looking electric guitars was great. And I went in there, into Jimmy’s front room … and he got his little acoustic guitar out and started playing away – it was great. He sang Buddy Holly songs. From then on we were just really close. His mum bought him a tape recorder and we used to make home recordings together. I think he sold them for a great sum of money to Immediate Records.’

Beck and Page began to spend afternoons and evenings at Page’s parents’ home, playing together and bouncing ideas off each other. Page would be playing a Gretsch Country Gentleman, running through songs like Ricky Nelson’s ‘My Babe’ and ‘It’s Late’, inspired by Nelson’s guitarist James Burton – ‘so great’, according to Beck. They would play back and listen to their jams on Page’s two-track tape recorder. The microphone would be smothered under one of the sofa’s cushions when they played. ‘I used to bash it, and it would make the best bass drum sound you ever heard!’ said Beck.

But this extra-curricular musical experimentation was not necessarily in opposition to what Page was doing on his art course at Sutton Art College: rather, these two aspects of himself complemented each other. Many years later, when asking Page about his career with Led Zeppelin, Brad Tolinski suggested that ‘the idea of having a grand vision and sticking to it is more characteristic of the fine arts than of rock music: did your having attended art school influence your thinking?’

‘No doubt about it,’ Page replied. ‘One thing I discovered was that most of the abstract painters that I admired were also very good technical draftsmen. Each had spent long periods of time being an apprentice and learning the fundamentals of classical composition and painting before they went off to do their own thing.

‘This made an impact on me because I could see I was running on a parallel path with my music. Playing in my early bands, working as a studio musician, producing and going to art school was, in retrospect, my apprenticeship. I was learning and creating a solid foundation of ideas, but I wasn’t really playing music. Then I joined the Yardbirds, and suddenly – bang! – all that I had learned began to fall into place, and I was off and ready to do something interesting. I had a voracious appetite for this new feeling of confidence.’

Despite starting his studies at Sutton, Page would, from time to time, step in during evening sessions with Cyril Davies’s and Alexis Korner’s R&B All-Stars at the Marquee Club and other London venues, such as Richmond’s Crawdaddy Club or at nearby Eel Pie Island. Soon he was offered a permanent gig as the guitarist with the R&B All-Stars, but he turned it down, worried that his illness might recur.

There was another guitar player on the scene at the time, a callow youth nicknamed Plimsolls, on account of his footwear. Although at first Plimsolls could hardly play at all, he was known to have a reasonably moneyed background that enabled him to own a new Kay guitar. He had another sobriquet, Eric the Mod, a reflection of his stylish dress sense, and he would shortly enjoy greater success when, rather like his idol Robert Johnson, he seemed to suddenly master his instrument, and he reverted to his full name: Eric Clapton.

Page recalled that one night after he had sat in with the R&B All-Stars, ‘Eric came up and said he’d seen some of the sets we’d done and told me, “You play like Matt Murphy,” Memphis Slim’s guitarist, and I said I really liked Matt Murphy and actually he was one of the ones that I’d followed quite heavily.’