По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

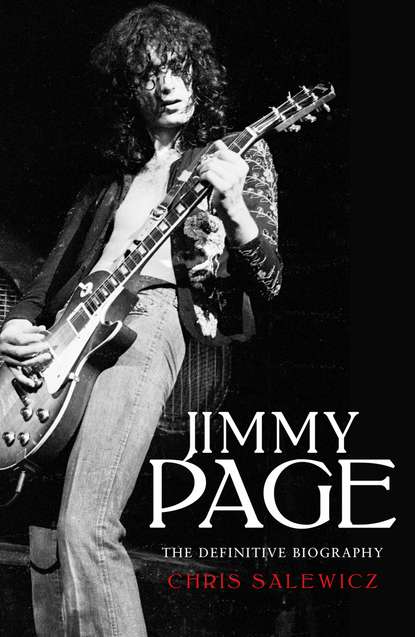

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It was thought,’ remembered Jim McCarty, ‘that maybe we could get Jimmy Page because Jimmy was the hottest session player, and Giorgio knew Jimmy. He asked Jimmy if he’d join the band but at that time Jimmy was so busy playing sessions that he wasn’t into joining a live band. He said why don’t you try one of my understudies, a guy called Jeff Beck. So we went down to see Jeff and asked him to join the band.’

Page’s friend Jeff Beck was playing with the Tridents, a rocking blues group he had joined in August 1964, never missing their weekly residence at Eel Pie Island, which would draw up to 1,500 people. Beck accepted the offer.

Page was still shadowed by the ill health that had dogged him during his time with Neil Christian and the Crusaders, and was also aware of the large amounts of money he continued to earn as a session player. But his main reason for turning down the offer, he said, was because of his growing friendship with Clapton. ‘If I hadn’t known Eric, or hadn’t liked him, I might have joined. As it was, I didn’t want any part of it. I liked Eric quite a bit and I didn’t want him to think I’d gone behind his back.’

(This was not the only act of generosity that Page displayed towards his friend Jeff Beck. When, in 1962, he announced he would be leaving Neil Christian and the Crusaders, Page had suggested Beck as a replacement for himself.)

Jeff Beck played his first show with the Yardbirds on Friday 5 March 1965 at Fairfield Halls in Croydon, south London, only two days after Eric Clapton quit the group. They were second on the bill to the Moody Blues, flying high for the first time with their hit ‘Go Now’.

Beck was so grateful that Page had recommended him as Clapton’s replacement that he went round to Page’s parents’ house in Epsom and presented his friend with his 1959 Fender Telecaster. ‘A beautiful gesture,’ said Page later. But Beck’s gratitude was realistic: although distinguished in his blues guitar band the Tridents, it was not until he joined the Yardbirds, whom he enriched with his fuzz-soaked solos, that he found the vessel for his upward flight into the guitar stratosphere. In fact, he soon borrowed a quite specific vehicle from Page: his Roger Mayer fuzzbox, on which Beck worked out the Eastern-flavoured riff for ‘Heart Full of Soul’, the first Yardbirds’ single he was involved in. ‘I still remember the time Jeff came over to my house when he was in the Yardbirds and played me “Shapes of Things”. It was just so good – so out there and ahead of its time. And I seem to have the same reaction whenever I hear anything he does,’ recalled Page.

‘The great thing about Jeff,’ said Chris Dreja, ‘is that his roots were also the blues and rock ’n’ roll, but he was also much wider in his musical tastes. And he had a mind and a talent that wanted to go much further than playing rock ’n’ roll and blues riffs, which was perfect for us because we were about to enter a phase of all sorts of experimentation. In retrospect we put Jeff under a lot of pressure. We would work on stuff and then bring Jeff in. Like, for example, the sitar sound he got on “Heart Full of Soul”. We brought in a sitar player … but it sounded thin and weedy. We said to Jeff, “Can you do it?” And he came in and created this incredible sound. Jeff Beck became a prototype of late-sixties psychedelia. He got chords from Stax and Motown records. The locked-up sound in the band gave it that sound.’

4

BECK’S BOLERO (#ulink_bd21aeda-7993-5da6-854d-cf770d2fa099)

It was in ‘the latter years of the first half of the 1960s’ that Jeff Dexter first encountered Jimmy Page. Dexter was a Mod scenemaker, the DJ at Tiles who, as a 15-year-old, famously demonstrated the Twist on BBC television; he had hung around the 2i’s Coffee Bar in London’s Old Compton Street, the seed-ground of British rock ’n’ roll, where Cliff Richard, among others, had been discovered, and would be instrumental in founding the Middle Earth venue, out of which sprang UK underground rock. ‘Jimmy was running around town at that time. But we really became friends about 1965 or 66. We both had an eye for a nice suit and a nice shirt.’

Page and Dexter would meet up in Soho to rummage through the wares of the area’s assorted rag-trade specialists, sometimes seeking cloth for jackets and trousers, more often looking for potential shirt fabric. An especial temple of suitably exotic material was found at Liberty, the Tudor-fronted department store on Great Marlborough Street. Armed with their cloth, they would then make their way to Star Shirtmakers on Wardour Street, two doors from the Whisky A Go Go. Star Shirtmakers was run by a Hungarian husband-and-wife tailoring team; they would knock up the fabric into shirts styled precisely as their customers desired, for – even then – the ludicrously cheap price of 11 shillings, the equivalent of 55 pence. (After the Beatles had been to their tailor, Dougie Millings, Dexter took them to nearby Star Shirtmakers, beginning a flood of celebrity shoppers at the place.)

One day, when they were leaving Liberty, Page and Dexter found themselves strolling down Kingly Street, which ran off the west end of the store. There they discovered an art gallery called 26 Kingly Street, with extraordinary lighting, sheets of Perspex and glittery screens. London’s first psychedelic gallery, 26 Kingly Street was run by Keith Albarn (whose son Damon is the singer in Blur). ‘We’d just discovered acid,’ said Dexter. ‘I tripped in Jimmy’s house but never tripped with him – I sought refuge with him a few times. I went to a Yardbirds rehearsal when I’d dropped acid. And he looked after me.’

Contrary to Billy Harrison’s dismissal of Page, Dexter insists that his friend was highly regarded on the London music scene, not simply for his musical accomplishments but as an empathetic human being. ‘He was a lovely chap. One of the boys. You’d see him at record launches, and the odd club – though he didn’t go to the Speakeasy as much as many others – and stuff like that. When I was running the Implosion shows Jimmy would come along. Ian Knight, my cohort on those events, went from Middle Earth to becoming the Yardbirds’ staging and lighting guy, and went on to have the same job with Led Zeppelin. We hung out at some of those crazy happenings, like the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream at Alexandra Palace.’

Page had moved up from Epsom and was living in a flat off Holland Road in west London, a thoroughfare that ran from Shepherd’s Bush to Kensington High Street; it was an area in which it seemed every single one of its myriad bedsits contained a hippie hash-dealer. In 1966 Dexter was invited to Deià in Majorca, home to a bohemian community, by Lady June, an artist and éminencegrise of the psychedelic scene. In Deià he encountered an especially louche breed of Portobello Road-style hippie chick, some of whom relocated back to London, becoming habitués of Blaises, a nightclub in South Kensington: ‘Jimmy and one of these dodgy birds used to get really stoned and play Buffalo Springfield again and again and again. “This is the direction I want to go in,” he would say. “I want to have a band that does magical things.”’

The folk scene, to which Page was always drawn, remained a prominent feature of Swinging London. ‘I used to go to Les Cousins,’ Dexter said of London’s dominant folk venue. ‘I was best friends with Beverley and John Martyn. Nick Drake only felt comfortable at their flat in Hampstead.’

Dexter was always impressed with Page’s phenomenal knowledge of art: ‘He was a collector. Of everything. He’s kept every piece of clothing he’s had since he was a child. His mother was incredibly neat and tidy. And so is he.’

Dexter also became friends with another woman who would have a significant impact on Page: a French model called Charlotte Martin. She was 20 when they first met, Dexter 19. ‘I first clapped eyes on her in a place called Westaway and Westaway, a fantastic shop near the British Museum that sold Scottish knitwear. All the young birds would gather there or at the Scotch House. She was a fabulous model who did it all: magazine level, and then once people saw how gorgeous she was she was employed all over the place. She did all the modelling with the Fool, for their collection. She was great friends with them because they all hung out at Eric’s place in the Pheasantry.’ ‘Eric’, of course, was Eric Clapton, and he and Charlotte Martin were an item.

By now Page had effectively dropped out of art college. Even though he would later acquire a considerable reputation for financial canniness, it is somewhat cheap to suggest that it was only his considerable earnings from session playing that continued to attract him to the craft. In fact, for him the art of recording, and coming to as full an understanding of it as possible, appears to have held far more attraction than treading the rock ’n’ roll boards. And in the most select quarters his skills were being further recognised. In August 1965 came the press announcement about the formation of Immediate Records, an independent label that was the pet project of Andrew Loog Oldham, Rolling Stones manager and wunderkind of UK pop, and his business partner Tony Calder. ‘Immediate will operate in the same way as any good, small independent label in America,’ said Oldham. ‘We will be bringing in new producers, while our main hope lies with the pop session guitarist turned producer Jimmy Page and my two friends, Stones Mick and Keith.’

Page had first worked with Andrew Loog Oldham in 1964, on one of Oldham’s versions of the Stones’ songs, performed by the Andrew Oldham Orchestra, part of his endeavour to become the UK’s Phil Spector. That session was at Kingsway Studios in Holborn, London; the producer was John ‘Paul Jones’ Baldwin.

Page then went on the road with Marianne Faithfull, who that summer had hit the Top 10 with her first release, ‘As Tears Go By’, written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, and on which Page had played.

Page had been recommended to Oldham by Charlie Katz, who booked musicians for his sessions. ‘He said to me one day, “There’s this young lad, Jimmy, we are trying him out. Why don’t you give him a go? He doesn’t read but Big Jim Sullivan will take him under his wing.” And so Jimmy started playing on my sessions,’ said Loog Oldham. ‘One of the first was Marianne Faithfull’s “As Tears Go By”. He was a bright spark. It was nice having him on the floor … All smiles and not much talk.’

Soon Page found himself playing on the Rolling Stones’ ‘Heart of Stone’, though it was a version that would not be released until the Stones’ Metamorphosis album, in 1975.

‘Jimmy was like a wisp,’ said Loog Oldham. ‘I don’t really know what kind of a person he was, because the great ones keep it hidden and metamorphose on us, so that the room works.’

Andrew Loog Oldham decided to take their relationship up a level, hiring Page as Immediate’s producer and A&R man. ‘In those days if you got on with people you tried to work with them. It seemed logical and Jimmy liked the idea … I thought he was very good. What he went on to do kind of proves it, doesn’t it?’

As for sessions with the Rolling Stones, Loog Oldham recalled: ‘He played on some of the demos Mick, Keith and I did that ended up on the album released in 1975 called Metamorphosis. The Stones did not play on that. I think he was on a Bobby Jameson single that Keith and I wrote and produced … I only considered people the way they considered themselves. Jimmy was a player, an occasional writer at that time with me and with Jackie DeShannon. I never considered him as a solo artist and I don’t think he did either.’

Page worked on a trio of demos for the Stones themselves: ‘Blue Turns to Grey’, ‘Some Things Just Stick in Your Mind’ and the aforementioned ‘Heart of Stone’. Although the version of ‘Blue Turns to Grey’ on which Page played was never released, a later edition of the song was included on the Stones’ 1965 US album December’s Children (And Everybody’s), and Cliff Richard’s cover of the song was a number 15 hit in 1966. ‘Some Things Just Stick in Your Mind’ and ‘Heart of Stone’ were included on Metamorphosis, the first song being covered by Vashti Bunyan for an unsuccessful release on Immediate.

What had specifically drawn Page to the Immediate production gig was the chance to work with his old mucker Eric Clapton, now with John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, who had formed an arrangement with the label.

In June 1965 John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers went into Pye Studios at Great Cumberland Place in London’s West End. Page was at the production helm for what would turn out to be a landmark session in the history of contemporary music.

‘I’m Your Witchdoctor’ and ‘Telephone Blues’ were the tunes involved. They featured John Mayall on keyboards, Hughie Flint on drums, John McVie on bass and Eric Clapton on guitar – the John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers line-up that had recorded the celebrated Beano-cover album. ‘When “Witchdoctor” came to be overdubbed, Eric had this idea to put this feedback wail over the top,’ said Page. ‘I was with him in the studio as he set this up, then I got back into the control room and told the engineer to record the overdub. About two thirds of the way through he pulled the faders down and said: “This guitarist is impossible to record.” I guess his technical ethics were compromised by the signal that was putting the meters into the red. I suggested that he got on with his job and leave that decision to me! Eric’s solo on “Telephone Blues” was just superb.’

It was Page who intuited how Clapton’s solos could be enhanced by pouring reverb onto them, bringing out the flames in his playing, characterised by Clapton’s overdriven one-note sustain.

But – as Page noted – Clapton’s plangent, lyrical playing on ‘Telephone Blues’, the B-side, is perhaps even more distinguished, the first time that he gets to really stretch out with a beautiful, mature stream of notes. You are struck by the clarity of the separation – and simultaneous harmony – of the instruments. Clearly Page had learned much from his countless hours in recording studios, learning to appreciate how the very best rock ’n’ roll records were assiduously constructed, put together piece by piece.

Tellingly, for his first go in the control seat for Immediate, the subject matter of the single’s title track alluded to the kind of dark material with which Page would later be associated, perhaps even tarnished by. The opening couplet ran:

‘I’m your witchdoctor, got the evil eye

Got the power of the devil, I’m the conjurer guy.’

On one hand this was no more than the stock imagery that peppered blues music; yet, in the bigger picture, it holds an interesting subtext. It was as though Page was toying with – giving a test run to, really – the entire mysterious and dark philosophy that would form the aura of Led Zeppelin.

‘The significance of this session cannot be emphasised enough, for it represented the birth of the modern guitar sound. And while Clapton did the playing, it was Page who made it possible for his work to be captured properly on tape,’ wrote Brad Tolinski.

That year Page also worked with the distinguished American composer Burt Bacharach on his album Hit Maker! Burt Bacharach Plays the Burt Bacharach Hits. ‘Page respected Bacharach’s meticulous approach to rehearsing and recording,’ wrote George Case in Jimmy Page: Magus, Musician, Man. Again, it was part of Page’s learning curve. ‘Bacharach, in turn, admired the young Briton’s politeness and polish.’

As part of his deal with Immediate, Page played guitar with Nico, a German actress, model and singer based in France whom Andrew Loog Oldham had met in London, where she was soaking up the scene. Loog Oldham and Page co-wrote a song for her, ‘The Last Mile’, and Page arranged, conducted, produced and played on the tune. It was relegated to the role of B-side, however, to the Gordon Lightfoot number ‘I’m Not Saying’ – again, Page played guitar on this track.

‘Brian Jones brought Nico to my attention,’ said Loog Oldham, ‘and Jimmy and I wrote a song, which we recorded with her as a B-side. It might have been better than the A-side. It should have been the A-side, because that was fucking awful. It really was stiff as Britain. Then he went on the road with Marianne Faithfull. We were all impressed by this new wave of women who were coming in.’

Page’s friendship with Eric Clapton continued to blossom, and soon Slowhand, as Clapton ironically became nicknamed, would often be accompanied by his beautiful French girlfriend, Charlotte ‘Charly’ Martin, who was friends with Jeff Dexter. Clapton met her in the Speakeasy nightclub in the summer of 1966, while he was forming his next group, Cream.

Problems with Immediate Records, however, almost created a rupture in the camaraderie between the two guitarists. Without informing Clapton, the label released some tunes that he had recorded onto Page’s Simon tape recorder when Clapton had stayed at his house – which led to Clapton mistrusting Page for a time. Yet this suspicion was misplaced. ‘I argued that they couldn’t put them out, because they were just variations of blues structures, and in the end we dubbed some other instruments over some of them and they came out, with liner notes attributed to me … though I didn’t have anything to do with writing them. I didn’t get a penny out of it, anyway,’ Page said, revealing what was for him generally a key subtext to any endeavour. (The musicians who overdubbed these instruments onto Clapton’s basic tracks were Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts and Mick Jagger, on harmonica.)

Born in 1939 in west London, Simon Napier-Bell was the son of a documentary filmmaker. After attempting to become a jazz musician in the United States, he drifted into music supervision for movies in Canada; eventually he returned to London, where he continued in the same line of work, including on the 1965 screwball comedy What’s New Pussycat? He expanded into the production of records and demos, and he would use popular London studios such as Advision on Bond Street and Cine-Tele Sounds Studios, popularly known as CTS, in Kensington Gardens Square, the top film-music studio in London. He would employ session musicians recommended by Dick Katz, who booked all the top players in London.

Highly intelligent and witty, Napier-Bell became something of an archetypal character of Swinging London, a gay man who was known for driving around in an imported Ford Thunderbird, a cigar clenched between his teeth. His best friend was Vicki Wickham, the producer of Ready Steady Go!, the hip pop music show broadcast every Friday night on ITV. Almost as a jape, he and Wickham co-wrote the English lyrics for the Italian ballad ‘Io Che Non Vivo (Senza Te)’, which had been featured at the 1965 San Remo Festival; their friend Dusty Springfield sang at the event and had been moved to tears by the song’s music and melody. Knocking up their set of English lyrics to match the music in an hour so that they could head out to a London nightclub, Wickham and Napier-Bell gave the tune its title, ‘You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me’. Recorded by Dusty Springfield, the song was a number one hit in the UK and number four in the United States; in subsequent years it would be a hit again many times over, across the globe, with even Elvis Presley doing a version of it in 1970.

By the time Napier-Bell wrote the ‘You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me’ lyrics, he was manager of the Yardbirds, having replaced Giorgio Gomelsky. That the talented and fascinating Gomelsky had been fired was perhaps not surprising; later he declared, ‘I should never have been a manager: I need someone to manage me.’ Though there were no suggestions of impropriety, the Yardbirds had dismissed him because of his inability to turn a profit for the group. All the same, Gomelsky had been an inspirational figure for the Yardbirds, under whose auspices they had become a hit recording act. During their first US tour in 1965 he had even secured a recording session at Sun Studio in Memphis with Sam Phillips, who had mentored Elvis Presley early in his career. The tune they recorded? The Tiny Bradshaw 1951 jump-blues classic ‘Train Kept A-Rollin’’, reworked in a rockabilly style by the Johnny Burnette Trio in 1956, and included on the Yardbirds’ US album release Having a Rave Up. ‘Train Kept A-Rollin’’ was a song that would replay significantly in the Yardbirds’ career.

‘Some time around the end of 1965 or the beginning of 1966,’ recalled Napier-Bell, ‘Paul Samwell-Smith, who played bass with the Yardbirds, called me. His girlfriend, later his wife, was Vicki Wickham’s secretary. I went to a gig the Yardbirds played in Paris. I quickly realised that a manager’s job was to keep the group together.’

Behind Napier-Bell’s management of the Yardbirds lay a continuous awkward subtext: ‘The Yardbirds were blokes in a pub talking about football. I was gay and couldn’t really enter into that world.’

During his time working in recording studios Napier-Bell had always employed session musicians. ‘You never think session players aren’t playing well: they know they are in the top league, the best in the world. They can play next to the guys in LA who would play with Sinatra.’

Napier-Bell’s first choice for guitarist was ‘always Big Jim Sullivan’. Even though, he says, ‘these guys were all infuriating. They’d put you through it. Big Jim Sullivan would always have a paperback book with him that he would read as you did a take: it would be balanced on his music stand. He would even read it halfway through the take until it came to his moment – he would be doing it to show off.’

If an additional guitarist was required, it would invariably be Page. ‘He and Big Jim would work out their parts between them. I talked to Jimmy Page enough to know he was a real session player. I knew he was a brilliant technician and admired by others. We’d also use John Paul Jones, who did all the arrangements for Herman’s Hermits. But I never really liked Jimmy Page. He had a sneer about him. At school the people who bullied me had this terrible, frightening sneer and Jimmy Page reminded me of those people. People who sneer have usually had unhappy childhoods.’

On 16 and 17 May 1966, at IBC Studios in London’s West End, Jeff Beck and Page were involved in what in retrospect can be seen as one of the very first super-sessions.