По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

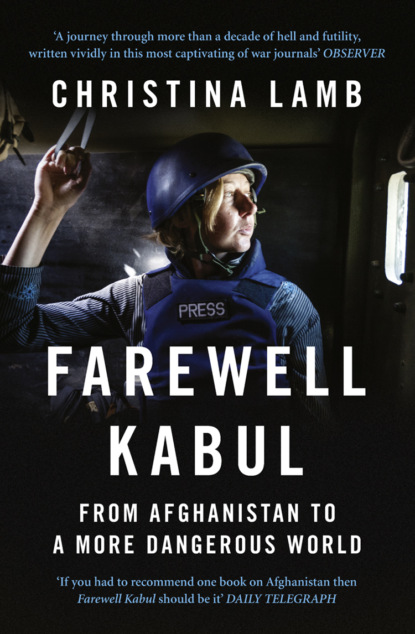

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The hawala system was often used by terrorist networks, as it was hard to trace, and was thus frowned upon by international agencies. Aid agencies and embassies bringing in millions of dollars were having to physically fly it in in suitcases. There were three different currencies in circulation, and the IMF suggested switching to dollars. Karzai refused, knowing this would not go down well with Afghans.

Nobody had a clue how much it would cost to rebuild Afghanistan, but one thing was clear – its financial system would have to be built from scratch. In this the country was lucky. Ashraf Ghani, a brilliant economist and anthropologist who had studied with Khalilzad at the American University in Beirut in 1968, had worked for years at the World Bank, and was eager to help. ‘The President had asked me five times to be his Interior Minister, but I believed that a functioning public finance system was the key to getting government right. That’s Islamic tradition. Umar, the second Caliph, established a public purse with enormous commitment to accountability and transparency.’

At fifty-eight, Ghani had lost much of his stomach to cancer, and could not eat proper meals, instead nibbling like a bird throughout the day. Not knowing how much time he had left, all he wanted to do was to help, and as quickly as possible. He arrived with Clare Lockhart, a fiercely bright British barrister who had worked with him at the World Bank. They found the Finance Ministry had no equipment, the central heating had not worked for more than twenty years, and there were no phones or lighting. ‘People were literally in the dark and the offices bare, as most of the furniture had disappeared,’ he recalled. Ghani went unpaid, as did many of his staff: ‘We used to joke we were the largest voluntary organisation in Afghanistan.’ They worked sixteen-to-eighteen-hour days, seven days a week. Like Jawad, they quickly discovered that the biggest problem was finding competent staff. ‘A limit was set of $50 a month for government employees, yet the UN and other international agencies were paying salaries twenty times as much. The net result was an exodus, with teachers and engineers becoming drivers, translators and guards for aid agencies, as they could earn more money. The international community actually led to the destruction of the government. In my view the international community actually worked against us. It took away our best people, and it dealt with and financed drug dealers and warlords.’

We journalists were equally guilty. My own interpreter, Fraidoon, was a gynaecologist, but earned more in a day with me than in a month working in the hospital. But if I hadn’t hired him, one of my colleagues would have. They were all using doctors or medical students. I tried to justify it, telling myself that the money would enable him to gain extra training, and I was happy when he did eventually end up working in a clinic in Herat.

‘Without human capital, financial capital is useless,’ Ghani would argue as he tried to persuade donors to create a school of public administration. ‘Billions of dollars have been spent in Afghanistan, but not one donor was willing to put up the $120 million needed. I cajoled, begged, threatened, but they wouldn’t give me.’

The government’s ability to raise revenue was hindered by corruption. ‘Too many people made a decision to prefer personal enrichment to public service,’ Ghani said sadly. ‘For someone to pay $1 in taxes they had to pay $8 in bribes, and waste a week of their life getting twenty signatures. Customs revenues were all disappearing, as provinces which had access to transit routes were taking the revenue without any legal authority. We had a payroll system where 25 per cent of salaries disappeared within ministries before they were paid, and no one had a clue how many employees there were.’ Fahim’s Ministry of Defence alone claimed to have 400,000 soldiers and officers. Ghani refused to give it any money any at all till Fahim agreed to reduce the number on the payroll to 100,000, then to reduce it every month on a sliding scale if accurate figures couldn’t be produced. By the time Ghani left office the number on the MoD payroll was 8,000.

There were other successes. A new currency was produced after Ghani used his connections to call Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve, who arranged a design and didn’t charge a cent. Twenty-eight billion new afghani notes were printed in Germany and Britain, and distributed with the rate fixed at fifty afghanis to the dollar.

Afghanistan had no functioning telephone system, but soon everyone seemed to be carrying a mobile. Ghani asked for assistance from Tony Blair, who sent a team of telecommunications experts for six months to draw up laws and issue licences for two networks. Within a short time these new phone companies were the country’s biggest taxpayers.

There was success too in health, with child mortality reduced by 15 per cent, though one in four children still died by the age of five, and Afghanistan remained the most dangerous place on earth to give birth.

Ghani became Karzai’s de facto Prime Minister. But his intolerance for corruption, combined with his abrasive manner, won him few friends. ‘It’s a miracle I’m alive,’ he would say. ‘By all odds I should be dead.’ He wasn’t referring to his precarious health. ‘President Karzai used to say there’s a long line of people who want to shoot me.’

His experience as Finance Minister left him exasperated with the international community. There was no coordinator, so he would have to waste time repeating things in numerous meetings with different countries or agencies which would often be replicating or undermining each other. Just in dealing with the Americans, there was the Pentagon, the CIA, Khalilzad, the Embassy and USAID, each of which often had a different agenda.

Like Jawad in the Presidency, Ghani frequently lost patience with his foreign advisers. ‘Technical assistance had become an unregulated industry,’ he complained. ‘Some things we needed help with, like the design of currency and drafting telecommunications laws. But certain American firms were paid by the number of people they put on the ground; so, for example, privatisation of public enterprises was not my priority, but one day I suddenly found an adviser on privatisation on my staff. There were others who didn’t know anything, and who we had to teach. They were being paid thousands of dollars, and they became part of the problem.’

One only had to go to Kabul airport to see a classic example of the aid community helping itself rather than Afghans. The scariest part of going to Afghanistan was flying in from Dubai on the state airline Ariana. Its planes were in such bad condition that they were banned from most places on earth. Even the model plane in the sales office was held together by sticking plaster and elastic bands.

The UN has its own airline to fly staff in and out of danger spots, so it quickly began its own service from Dubai or Islamabad to Kabul. As I stood nervously fiddling with my Ariana boarding pass, I would enviously watch the foreign aid workers and diplomats boarding the shiny UN planes. What I didn’t realise was that the millions of dollars to subsidise this service was coming from the money pledged to help Afghanistan. Ghani was indignant. ‘The first thing the UN system provided through the $1.6 billion of donor money channelled to UN agencies in 2002 was an airline devoted to serving UN staff, and occasionally (after much lobbying) some Afghan government officials.’

While nobody would give Ariana the $100–200 million investment to turn it into a proper, commercially viable airline, Ghani believes the UN was subsidising its own airline by as much as $300 million. As the UN has never disclosed the cost of its operations, the actual figure is unknown. ‘There is a clear double standard between the UN staff, who need to fly on a safe airline, and the leaders and nationals of a country, who are confined to flying with an unsafe airline,’ said Ghani.

At Ghani’s urging, Karzai tried to boost government revenue by demanding that warlords who had become Governors or border police chiefs hand over the customs duties they collected. According to Finance Ministry estimates, in 2002 $500 million had been collected for goods moving in and out of the landlocked country, but only $80 million handed over to the central government. As Governor of Herat, Ismael Khan was the worst culprit, with the crossing points from Iran and Turkmenistan both falling into his fiefdom, earning him as much as $1 million a day. When Karzai demanded he hand some of this money over Ismael instead sent him back a bill for development in his province.

Finally, in desperation, in May 2003 Karzai summoned a dozen of the warlords and Governors and threatened to resign if they refused to hand over the customs revenues. A few weeks later two Toyota Land Cruisers arrived at the Ministry of Finance with $20 million in cash.

Emboldened, Karzai tried to take on Ismael and appoint his own police commissioner and military chief for Herat. Ismael had 20,000 men under his command, including special forces who skinned live snakes with their teeth, and was not to be messed with. He continued to receive support from the Iranians, as he had for years. Their influence was becoming very visible in Herat, and Ismael played them off against the Americans, who also had him on their payroll.

When Karzai dismissed his men, Ismael grabbed forty of his commanders and flew to Kabul to confront him. I met them in the House of Heratis in Kabul. Ismael was disdainful of Karzai, and expressed outrage at the state of the roads in Kabul. ‘Look at this mess,’ he said, pointing at all the mud and potholes and endless traffic jams. In Herat, being a warlord, he had simply bulldozed homes and shops to widen the roads, and no one argued.

Ismael flew back, his men reinstated. A year later, fed up with still receiving none of the customs revenue, Karzai sacked Ismael as Governor. Angry riots broke out across Herat. Khalilzad says it was he who finally persuaded Ismael to go. ‘Karzai wanted me to play the heavy guy. I had to go to Herat and hold his hand and then have a press conference saying Amir Ismael Khan has decided to move to Kabul.’

This naturally made it look even more as though Karzai had no control. Ismael was given the Ministry of Energy, where it was felt he could do less damage. As only about 6 per cent of Afghanistan had electricity, inevitably he became known as ‘Minister of Darkness’.

Dostum also finally went too far that year, fighting against Karzai’s chosen Governor in the northern province of Faryab, then refusing to allow newly trained soldiers from the Afghan National Army (ANA) to pass through his home area of Shabargan on their way to Herat.

‘If you send them there we will put them all in body bags. We’ll make it worse for you than Vietnam,’ he told Khalilzad.

‘Do you understand there are Americans with ANA, so an attack on the ANA is an attack on Americans?’ replied Khalilzad. ‘This is a bridge once you cross, you can’t come back.’

Dostum would not listen. ‘He was clearly drunk,’ said Khalilzad. ‘I told him, “You need to drink lots of tea and coffee, then we’ll talk when you’re sober.” Instead he phoned Karzai to complain that I was the worst of the Americans. When he called me a couple of hours later he still refused to let the troops through. So I got B1s to fly from Diego Garcia over his house repeatedly, breaking the sound barrier.’

The show of force was something Dostum understood. When he called again, Khalilzad told him to move to Kabul and stop causing trouble. He moved into a house in Wazir Akbar Khan, the city’s most affluent suburb, favoured by warlords and aid agencies, and named after the Afghan hero who had captured the garrison from the British. Dostum had the house painted lavender, and set up his own TV station called Ayna, which means ‘mirror’. A TV station had clearly become the latest warlord accessory – Sayyaf also had one.

Meanwhile, trapped inside his palace, Karzai had become mockingly known as ‘the Mayor of Kabul’. His weakness was evident when he tried to stop warlords bringing their own armies into the Presidency. ‘They were coming for meetings with private militia of anywhere between six and sixty undisciplined, untrained people carrying very dangerous heavy weapons,’ said Jawad. But when in 2003 the palace imposed a rule that only a few guards could come into meetings with the President, it was met with outrage. ‘What do you mean?’ they’d say. ‘I’m a resistance leader. I fought the Soviets. Nobody stops me!’

‘We had people drawing guns at the palace guards,’ recalled Jawad, ‘and got very close to shooting.’

Yet Khalilzad believes Karzai had much more power than he himself imagined. ‘He got himself into this situation. I told him, “Can you imagine Dostum going back to the mountains? They are all too fat and rich.” I just don’t think Karzai ever got comfortable with using the military, with the shadow effect of force.’

Jawad argues it was not so easy. ‘Should Karzai have challenged the warlords? Maybe. But I think he knew that he didn’t have enough resources and forces to take them on, and he didn’t have support from outside. The Americans talked about promising support, but when it came to take decisive action against spoilers they’d back off, using this term “We don’t want to be involved in a green on green confrontation.” The warlords were getting a lot more than we were, so how could he take a stronger stand? Even his own personal bodyguards were Fahim’s men, then later on Americans.’

It was Fahim who was behind a scheme that prompted Karzai’s greatest anger with the warlords. With all the people coming back to Afghanistan and all the foreign agencies that had moved in, Kabul had a major shortage of real estate, and property prices were booming. Just a couple of miles down the road from the palace, on the edge of affluent Wazir Akbar Khan, was an area called Shirpur. Fahim came up with a plan to distribute plots to military officers and cabinet colleagues for just $1,000 each. Not only were the plots actually worth at least $100,000 each, but there were more than thirty families living on the land, in houses they had been in for twenty-five years. In September 2003, when they ignored requests to leave, the Kabul police chief sent in bulldozers and men with sticks. According to the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission all but four of the thirty-two cabinet Ministers had accepted a plot, as well as many senior military officers.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: