По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

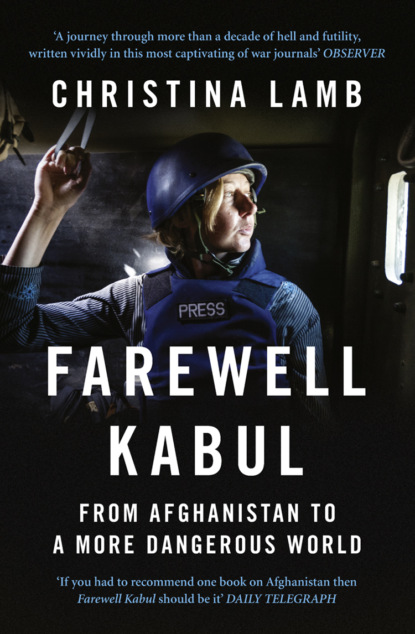

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It all took so long that when I finally got back outside my driver had disappeared. ‘He’s a hashish smoker and gone to the place where they smoke hashish,’ the guard told me helpfully.

No wonder most people just wandered to the side of the border posts. If Afghan democracy came with endless shakedowns I began to understand why people had initially welcomed the Taliban.

Back in Quetta, this time hidden under a burqa and staying in the curtained-off purdah quarters of a friend’s house, I received a coded message in a telephone call shortly after breakfast on the second day. ‘The carpet has arrived,’ said a voice. ‘It’s a very valuable one, and we can’t keep it here long for security reasons.’

Haste is a relative concept in Pakistan, and it was four hours before the car arrived to pick me up. We drove past the bus station, where a man was holding a muddy pelican on a string, and through the bazaar. I was told to go inside a tailor’s shop with shelves lined with giant rolls of dress material. A door at the back led out onto a rubbish-strewn alley where a man on a motorbike was waiting. We sped down a few roads and into a small mud-walled compound, the home of a local religious leader. I was beckoned into the women’s quarters, where a couple of women lifted my burqa over my head. Finally a bearded old man in a swan-white turban summoned me through the dividing curtain into a room with a large roaring fire. Inside, two men were sitting on floor cushions – the two Taliban Ministers who had agreed to meet me.

It was the strangest feeling. For most of the five months since 9/11 I had been in Pakistan and Afghanistan writing about the evil Taliban regime and meeting one after another of its victims. I had met Hazara women whose husbands had been burned to death in front of their eyes, a Kandahari footballer whose hand was cut off in a public amputation at which officials then discussed whether to also chop off a foot, and a man who had worked as a torturer and was trying to devise ever more cruel tortures.

For a moment I was taken aback. These were some of the world’s most wanted men, but with their beards trimmed short, they looked surprisingly young. I knew the Taliban leadership were mostly in their thirties, but somehow I had thought of them as bigger and older – and more malevolent.

One of the pair, Maulana Abdullah Sahadi, the former Deputy Defence Minister, was only twenty-eight, and looked vulnerable and slightly scared, greeting me with a wonky Johnny Depp-like smile. He told me it was the first time he had ventured out of his hiding place since escaping Afghanistan after the fall of Kandahar two months earlier.

The other Minister, a burly man in his mid-thirties who had agreed to meet me only on condition of anonymity, was responsible for some of the acts that have most horrified the Western world, and looked defiant. After a while we were joined by the Director General of the Passport Office who had issued Afghan visas to some of the Arab fighters who were on America’s most-wanted list.

‘You see, we don’t have two horns,’ said the older Minister with a smile as he poured me tea from a golden teapot and offered me boiled sweets. ‘Now anyone can say anything about us and the world will believe it. People have been saying we skinned their husbands alive and ate babies, and you people print it.’

We started off talking about how they had joined the Taliban. Maulana Sahadi told me his family had moved to a refugee camp in Quetta when he was just five after his father, a mujahid with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Hezb-i-Islami, was killed fighting the Russians. The family was very poor, surviving much of the time on bread begged or bought with money earned from sewing carpets, so his mother was pleased when he got a place at a madrassa at the age of eight. His food, board and books were all provided. At some point he learned to use a Kalashnikov, though he would not say at what age, claiming, ‘A gun is such a thing, one day you use it, the next day you master it.’

In mid-1994 a delegation of elders and ulema, or religious scholars, from Pakistan came to the madrassa. ‘They issued a fatwa telling us we must join the Taliban and fight jihad. I joined with a group of friends from the madrassa, so we were there right at the very beginning, in the first attack on Spin Boldak that October. At that time we were only about a hundred people. We were killing men and many of our companions were martyred, but we were happy because we were doing it for Islam. We were the soldiers of God.’

Sahadi went on to fight in battles all over Afghanistan, including Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kunduz and Bamiyan, commanding five hundred men, then 2,500, then becoming Director of Defence. ‘I would motivate my troops before fighting by telling them that if they were martyred they would go to paradise and could take with them seventy-two of their family members.’ He got on well with Mullah Omar, whom he described as ‘a very nice, good-natured person with good morals. He treated me like a son. Whoever came to him, he treated with respect.’

Eventually, in 1999, Sahadi became Deputy Defence Minister to Mullah Obaidullah. As such he had frequent personal contact with bin Laden, though he insisted that ‘the Arabs were not controlling things. Anyone who supports Islam was welcome in our country – we had British, Americans, Australians.’

Sahadi told me how during the American bombing offensive, he and his colleagues had to keep changing houses in Kandahar to avoid being hit. But he said the Taliban leadership never contemplated handing over bin Laden to save themselves. ‘He was a guest in our country, and we gave him refuge because hospitality is an important part of our code of behaviour. Besides, he was supporting us, giving us money, when no one else was.’ He also complained that the Americans had not given the evidence they had asked for to show bin Laden’s complicity in the 9/11 attacks: ‘The Taliban leadership do not believe the Twin Towers attack was carried out by al Qaeda. According to my own opinion, the attack was wrong. It is not Islamic to kill innocent people like that.’

The other Minister interjected. ‘What this war is really about is a clash between Islam and infidels. America wants to implement its own kafir religion in Afghanistan. We are the real defenders of Islam, not people like Gul Agha [the Governor of Kandahar] and Hamid Karzai. They are puppets of America.’

But why, then, did the Taliban collapse so easily? ‘We’re not broken, we’re whole,’ insisted Sahadi. ‘We weren’t defeated, we agreed to hand over rather than fight and spill blood. Our people went back to their tribes or left the country. Now we are just waiting. Karzai cannot even trust his own people to guard the presidential palace, but has to have American troops. We are regrouping. We still have arms and many supporters inside, and when the time is right we will be back.’

How had they escaped Afghanistan? ‘We shaved off our beards, changed our turbans from white Taliban to Kandahari [green or black with thin white stripes], got in cars and drove on the road across the border. My beard was as long as this,’ he said, gesturing down to his chest. Among those who had headed across the border were Mullah Turabi, the Justice Minister; Abdul Razzak, the Interior Minister; Qadratuallah Jamal, the Culture Minister; Mullah Obaidullah Akhund, the Defence Minister; and Mullah Baradar, deputy to Mullah Omar. The local Pakistani authorities, he claimed, not only turned a blind eye but helped.

‘Thank God this war happened, because now we really know who is with us and who is against us,’ added Sahadi. ‘Karzai went to the other camp. Once he pretended he was with us, but now we see he just wanted power. They will all be brought before justice and punished according to Islamic law. The Americans are celebrating victory, but they have failed. They have not caught bin Laden or Mullah Omar. All they have done is oust our government. We never did anything to them. Mullah Omar is still in Afghanistan [between Uruzgan and Helmand], and will stay there making contact with those commanders unhappy with the new government. You will see Islam will win out and we will break the Americans into pieces as we did with the Russians and, inshallah, bring back the name of the Taliban.’

I was intrigued, but feared lingering longer in case word of my presence got back to the authorities. The nameless Taliban smiled as I left. ‘You see, unlike you people, we are not in a hurry.’

A week later I was back in Kabul, and went to the headquarters of the ISAF peacekeeping forces, then under the command of the British general John McColl. I asked what they thought about Taliban living freely in Pakistan. They weren’t much use, pointing out that they weren’t allowed outside Kabul, and their job was ‘stabilisation’, not to hunt down militants – that was down to Operation Enduring Freedom, the US forces.

So I went to see the Americans. If I could find Taliban Ministers, then surely they could. Yet by that point only one senior Taliban had been arrested – Mullah Abdul Wakil Muttawakil, the Taliban’s Foreign Minister; and that was only because he surrendered to Afghan officials in Kandahar. He had actually offered to cooperate with the US forces, but instead they imprisoned him in Bagram, which no doubt deterred other Taliban from coming forward.1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Nobody seemed interested. The Taliban was gone, as far as they were concerned. ‘If these are senior Taliban officials, maybe the Pakistani authorities should be arresting them,’ shrugged one US official. ‘Frankly there was no great interest on the part of the Pakistanis in catching Taliban, and it wasn’t our priority,’ said Bob Grenier, who was CIA station chief in Pakistan at the time. ‘I suppose we might have kicked and screamed and held our breath and demanded “By God you’ve got to get these guys,” but that might actually have undermined our efforts in what was for us the greatest priority, and where we already had their active cooperation, which was al Qaeda. I didn’t see any particular reason to do that.’

The lack of will to do anything about the Taliban was infuriating President Karzai. He told me he had even given the Americans the names and addresses of Taliban in Quetta. Both he and his Foreign Minister Abdullah Abdullah had used their visit to Washington in January to ask the Bush administration to pressure Pakistan. ‘I told the Americans I know the Taliban leaders are in Pakistan,’ said Abdullah. ‘But they were only interested in al Qaeda, and for that they believed they needed Musharraf.’

After going to Washington, Abdullah went to see Musharraf. ‘He told me, “ISI is now under my control, previous governments didn’t control it but I’ve sacked eighty people.” Then he told me his brother was visiting from the US, and said he’s a very free kind of person who likes to travel and wanted to go to Kabul. Musharraf said, “I told him no, it’s not safe,” but then said, “I’ll send him in a bus with my ISI.” I couldn’t believe he was so blatant.’

The very week I was meeting Taliban in Pakistan, Musharraf was being fêted in Washington on his second visit since 9/11. He met Vice President Dick Cheney and had lunch with President Bush at the White House. ‘President Musharraf is a leader with great courage and vision,’ said Bush. ‘I am proud to call him my friend.’

On 12 February 2002, while Musharraf was in Washington, the Pakistan government announced that it had arrested a British-born Pakistani called Omar Saeed Sheikh for the kidnapping of Daniel Pearl. A graduate of the London School of Economics, this was not the first time twenty-seven-year-old Sheikh had been involved in a kidnapping. He had served time in an Indian jail for the kidnap of four Western tourists in Delhi in 1994. Pretending to be a local, he had befriended the three British and one American travellers and invited them to what he said was his village. They were freed by Indian police and he was jailed till 1999, when he was released in exchange for 155 hostages on an Indian Airlines plane that had been hijacked to Kandahar.

Mysteriously, Sheikh turned out to have been staying with retired ISI brigadier Ejaz Shah for a week before being handed over to Pakistani police working with the FBI hunting for Pearl in Karachi. Nobody explained why Shah did not turn him in earlier. The CIA believed Sheikh had been working for ISI. Even once he was in police custody, it was a month before the FBI were allowed to interview him. By then it was too late. What we didn’t know when Sheikh’s arrest was announced was that the thirty-eight-year-old Pearl was already dead. Nine days later, on 21 February, a video was handed to the US Embassy entitled ‘The Slaughter of the Spy-Journalist, the Jew Daniel Pearl’. The horrific footage, showing a knife slitting Pearl’s throat and beheading him, was the first al Qaeda execution recorded on video.2 (#litres_trial_promo) It ended with the captors demanding the release of all Muslim prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, and warning that if their demands were not met they would repeat the scene ‘again and again’.

Pakistan refused to extradite Sheikh. When asked about this, Musharraf said, ‘Perhaps Daniel Pearl was over-intrusive. A media person should be aware of the dangers of getting into dangerous areas. Unfortunately he got over-involved.’

Pakistani generals were astonished that the US hadn’t committed more troops to Afghanistan, and that they had allowed bin Laden and so many al Qaeda fighters to escape. Throughout 2002, ISI sent memos to Musharraf saying that the Americans were clearly not interested in Afghanistan and would soon leave, and that the Taliban should be kept as an option.

In February 2003 Mullah Omar emerged from silence with a letter faxed to a Pakistani newspaper, calling on all Afghans to rise up against the Americans and the Karzai government: ‘The Afghans should abandon the ranks of America, the crusaders and their allies, and should immediately start a jihad. Vacate all offices, ministries, provinces so that the distinction between a Muslim and a crusader is made.’

A few weeks later I went back to Quetta, and found the Taliban were no longer in hiding. World attention had moved on to Iraq, where the US was poised to invade any day, and the city had become Taliban Central.

Umar took me to Mizan Chowk, a busy square. Men in black turbans, their eyes lined with black kohl, wandered about openly, exchanging the typical lengthy Pashto greetings. Newsstands openly sold Taliban CDs and tapes, including one of Mullah Omar’s speech.

We visited the New Muslim Speeches Music Shop, which displayed posters and stickers depicting grenades, handheld rocket launchers and other jihadi weapons of choice, imprinted with slogans calling for youth to rise up against the West. Inside were a group of younger men with tightly wound turbans and trousers cropped way above the ankle, which was typical of Taliban. They seemed galvanised by Mullah Omar’s call to arms. ‘We fought before to liberate our country, and we will fight again,’ said one. ‘Now it is time to expel these infidels from our land.’ They told us that they had been in Kandahar when the bombing started, and had come into Pakistan – white flags were flown near the border to tell them it was safe to cross.

One told us that ISI was giving them satellite phones, Toyota pick-ups and motorbikes. Once again the agency was running training camps, just as it had during the jihad in the 1980s, and bringing in arms shipments and funds from the Gulf.

I was fascinated and wanted to talk longer, but my presence was drawing attention, and Umar was growing nervous. He pointed out a car with dark-tinted windows that had stopped nearby.

Later we heard that Taliban commanders were being threatened that if they did not return to the fight, ISI would hand them over to the Americans, and they’d end up in Guantánamo.

After I wrote about what I had seen, Pakistan’s Embassies started excluding Quetta when they issued visas to journalists. ‘It’s for your own safety,’ said the smiling Press Minister at the High Commission in London. ‘But I have friends in Quetta who will keep me safe,’ I pleaded, to no avail. The handful of other journalists who sneaked in were beaten up or arrested, like my good friend Marc Epstein from the French magazine L’Express and his photographer Jean-Paul Guilloteau, who were picked up in December 2003 and held for almost a month. Their fixer Khawar Mehdi Rizvi was accused of sedition, conspiracy and impersonation of Taliban, and was tortured while in jail. He later went into exile in the US, as many Pakistanis have been forced to do.

Next time I got a visa it was stamped ‘Islamabad Only’. ‘No country in the world issues visas just for the capital city,’ I protested.

Back home, I met up with an old friend from ISI in a south-west London bistro full of yummy mummies and ladies who lunch. ‘We never had this conversation,’ he said as we started our soup. ‘What you have to understand is everything we do to cooperate with the Americans there are others who work in the opposite way.’ He referred to what he called ‘the shadow organisation’ – the first time I heard about the so-called ‘Sector S’ – explaining that Pakistan needed to keep its options open, so ISI had an entire group of people who were officially retired, perhaps heading ‘welfare organisations’, but were still training and advising Taliban. ‘It’s all about deniability,’ he said. If any of them were caught, they would be shrugged off as ‘rogue elements’.

My soup got cold as I sat open-mouthed, wondering if Pakistan really could pull the wool over the eyes of the world’s most powerful country. ‘Does Mullah Omar even exist?’ I asked.

‘There is a man with one eye and limited intelligence called Mullah Omar, if that’s what you mean,’ he chuckled. ‘You saw what happened to Danny Pearl,’ he said, as all around us the bistro tinkled with the laughter of gossiping women and small children and sunlight. ‘If I were you, I would know this: I would eat my lunch and I would investigate no further.’

8

Merchants of Ruin – the Return of the Warlords (#ue110efdd-99ae-5c21-ae82-f889fc3c445e)

Jalalabad, 2002

Hazrat Ali was eager to show off his new toy, a top-of-the-range Toyota Land Cruiser. He had left the factory plastic wrapping on the tan leather seats so they did not get sullied by the gunmen he always travelled with. ‘Look!’ he said, jolting us all in our seats as he fired the vehicle dramatically into reverse. The sensor beeped insistently as it tried to cope with warning of old men on bicycles, chickens, a stray goat, a beggar on stumps and all the usual mêlée of an Afghan street. Best of all was the flashing computer console on the dashboard, with satellite TV and GPS. The only problem was, it was programmed in Japanese, and there were no maps available for Afghanistan.

Hazrat Ali didn’t care. Perhaps because their own land is so devoid of modernity and so drained of colour, Afghan commanders adore glitter and gizmos. In the days of the war against the Soviets in the 1980s it was flashing fairy lights round the windscreen, or my personal favourite, a brake pedal which when pressed intoned ‘Bismillah’ – In the name of Allah.

The paymaster for Hazrat Ali’s latest car was the same – and as they always did back then, he had hung a sickly-sweet pine-tree air freshener from the rear-view mirror – but this was a whole new scale of warlord gadgetry. Black Toyota SUVs were the vehicle of choice of Third World militias, and he had just taken delivery of a fleet of six spanking-new ones, cementing his status as the biggest warlord in Jalalabad.

I was sitting in the restaurant of the gloomy Spinghar Hotel, staring at the one-item lunch menu – ‘Chicken kerahi or not’ – with my gloomy interpreter Dr Rais when we heard a vehicle roar up outside. It had a Dubai number plate, and I could tell it was one of Hazrat Ali’s as it had a large poster on the back of the late Ahmat Shah Massoud, the Northern Alliance leader for whom he had fought. Out jumped five men in khakis clutching AK47s and grenade launchers, walking straight past the ‘No Kalashnikovs’ sign at the hotel entrance. They were my escort.

We sped through the city, which it was hard to imagine had once been the winter capital of the royal family, a place of palm trees and orange groves. The old palaces were all in ruins, but Dr Rais pointed out the tomb of King Habibullah, the son of Abdur Rahman. Like most Afghan Kings, he had been assassinated – in his case while on a hunting trip nearby in 1919. The garden was overgrown and scattered with old iron bedsteads and chairs, among which some men were scavenging for anything they might sell. ‘The merchants of ruin,’ sighed Dr Rais poetically.

In the distance we could see the Tora Bora mountains where Osama bin Laden had last been seen. Since then his only manifestation was on the occasional video or tape recording.