По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

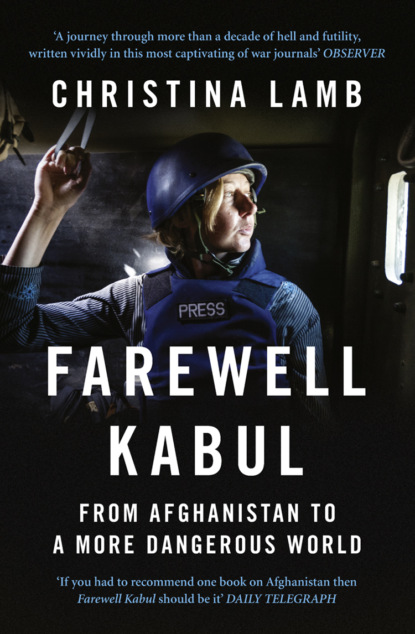

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Bin Laden’s first wife Najwa was horrified when her husband came back from Afghanistan to their home in Jeddah with ‘red raised scars all over his body’ and boasting he had learned to fly a helicopter. She was his cousin from Syria and they had married in 1974, when she was just fourteen and he seventeen, and she might reasonably have expected an easy life after marrying into one of the richest families in the Middle East.

Instead she found a fanatic who refused toys to his children, or to let his family have air conditioning to relieve the sweltering desert heat. Yet initially she was proud. ‘Everyone was astonished that a wealthy bin Laden son actually risked death or injury on the front lines,’ she later wrote. ‘I heard silly talk that many people wanted to inhale the very air Osama breathed.’ She was less impressed when he took their eldest son Abdullah to Jaji to experience jihad at the age of just nine.

Bin Laden became known as ‘the Sheikh’, and his growing reputation led to inevitable rivalry with his former mentor Azzam, though he continued to finance MK. Then one day, visiting some of his wounded fighters in the Kuwaiti Red Crescent hospital in Peshawar, bin Laden met an Egyptian eye doctor called Ayman al Zawahiri.

Bin Laden had long been anti-American, his wife Najwa complaining that his children were not allowed to have Western products such as Coca-Cola or television. But his focus had always been on expelling infidels from Afghanistan, and he had never talked of opposing the Saudi monarchy or other Arab regimes.

That changed after he met Zawahiri. At thirty-five, Zawahiri was seven years older than bin Laden and much more of an intellectual, and he gradually took Azzam’s place as his mentor. The two men made an unlikely pair, one tall and lean, the other portly and bespectacled, but they found much in common. The Egyptian had grown close to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, but was otherwise condescending about the Afghans, who he did not think knew the first thing about Islam. To him they were simply tools. He agreed with bin Laden about the need to create an all-Arab force, and had gathered around him a small cadre of well-educated doctors and engineers from Egypt, many of whom had already been imprisoned and tortured for their beliefs. By then several of bin Laden’s key men were Egyptian radicals.

In May 1988 the Soviets began pulling out troops from Afghanistan in a phased withdrawal that would take nine months, and the two men began looking to the future and what they could do next. In August 1988 they officially formed an organisation called al Qaeda, which meant ‘the Base’, the hub for what was to be the first terrorism multinational, and whose members would pledge the bayat, an oath of allegiance to bin Laden.

After the defeat of the Soviet Union in 1989, and the failure of the mujaheddin to take over Afghanistan, bin Laden left Peshawar disillusioned, and eventually set up operations in Sudan. In 1996 the government there expelled him under American pressure, and he flew back to Afghanistan. He made Tora Bora his base, moving in with his three wives and twelve of his seventeen children, and joined by many al Qaeda fighters.

His son Omar hated it there, and later described surviving on eggs, rice and potatoes, with no electricity or running water – hardly the life of a Saudi millionaire. Bin Laden got to know the mountains well, taking hikes with his sons, and learning centuries-old trails used by smugglers and traders into Pakistan.

In the following years, his men stockpiled weapons and fortified an area about six miles square between the Wazir and Agam valleys. Some of their caves were reported to be concealed 350 feet inside the granite peaks. It was, in other words, an obvious hide-out and escape route.

Gary Berntsen, a tall man with cold blue eyes, had been in the last CIA team to go into Afghanistan before 9/11 – a trip to the Northern Alliance in 2000, though they were quickly pulled out and he ended up in Latin America. After the attack he was sent back in late October 2001, his team replacing that of the other Gary, Gary Schroen, in northern Afghanistan. By mid-November the capital had fallen, and he was running CIA operations from a Kabul guesthouse when the first reports came in that bin Laden was in Tora Bora. He went straight to Major General Dell Dailey, the US special forces commander at Bagram, and asked for an SF team to go down there together with some of his agents. When I met Berntsen afterwards, he told me Dailey had said, ‘We’re not going to – it’s too disorganised, too dangerous, too this, too that.’9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Berntsen decided that if the special forces wouldn’t go, he would mount his own operation. ‘Bin Laden killed 3,000 Americans in my city New York, and I wanted him dead. Simple as that,’ he said. ‘I wasn’t going to ask for permission, because I knew I wouldn’t get it. I knew if I didn’t do anything bin Laden would escape the country with his entire force, so I just improvised.’

He sent a small team of eight men to Jalalabad, where they began coordinating with local commanders. In late November four of them with ten Afghan guides set off into the mountains, scaling 10,000-foot peaks. Their equipment was packed onto mules (one of which was blown up when an RPG round on its back detonated). They knew they faced an enemy who outnumbered them by perhaps hundreds to one. ‘I sent four guys into those mountains alone to look for a thousand people,’ said Berntsen. ‘It was a very, very large risk. If they’d been found they would have been tortured and killed, and I would probably have been fired.’

After two days they spotted bin Laden’s camp, complete with trucks, command posts and machine-gun nests. They estimated there were between six and seven hundred people there. ‘We got them,’ they radioed Berntsen, who punched the air in delight. ‘One word kept pounding in my head: revenge. Let’s do this right and finish them off in the mountains.’

The agents mounted their laser marking devices on tripods and began lighting up targets using lasers invisible to the naked eye. To be doubly sure, one of them punched coordinates into a device that looked like a gigantic palm pilot. For the next fifty-six hours they directed strike after strike by B1 and B2 bombers and F14 Tomcats onto the al Qaeda encampment. The battle of Tora Bora had begun. But there was a fatal flaw. They might have the world’s most overwhelming air power and sophisticated communications system on their side, but at the end of the day they were just four Americans against perhaps a thousand men.

As the bombardment went on, bin Laden and his men fled further into the mountains. A twelve-man special forces team was sent in, as well as some crack SAS operatives. The plan was to pin the al Qaeda fighters against the mountains, using Afghan forces to trap them in a ‘kill-box’ between three promontories. Three rival local commanders who between them controlled most of Jalalabad were hired – Hazrat Ali, Haji Zahir and Haji Zaman Ghamsharik – and a day rate of $100–150 per soldier agreed. ‘I raised an army with a couple of million dollars,’ says Berntsen. But he doubted that they were really committed.

Hazrat Ali – or ‘General Ali’, as he called himself – had fought the Soviets as a teenager in the 1980s, and later joined the Taliban for a time. Haji Zahir was the nephew of Abdul Haq, who had been executed by the Taliban the previous month. Haji Zaman was a wealthy drug smuggler who had also fought the Soviets, but when the Taliban came to power he went into exile in France. He had been persuaded by the United States to return to Afghanistan.

Between them they fielded a force of around 2,000 men, but there were questions from the outset about the competence and loyalties of the fighters. The warlords and their men distrusted each other, and all appeared to distrust their American allies. According to Hayatullah, head of a group called the Eastern Council whose cousin Rohatullah also had men there, Hazrat Ali and Haji Zaman each got $6 million, but then Haji Zahir said the Americans had so much money they hadn’t asked for enough, and should have demanded $100 million.10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Berntsen was certain bin Laden was at Tora Bora, because a second CIA team he sent in had a stroke of luck. One of the dead bodies they found was clutching a cheap Japanese walkie-talkie. Through it they could hear bin Laden exhorting his troops to keep fighting.

‘We were listening to bin Laden praying, talking and giving instructions for a couple of days,’ said Berntsen. ‘I had a guy called Jalal, the CIA’s number-one native Arabist, who’d been listening to bin Laden’s voice for five years, down here listening. Anyone who says he wasn’t there is a damn fool.’ Berntsen sent an urgent request to General Franks at Central Command in Florida for a battalion of six to eight hundred US Army Rangers to be dropped behind the al Qaeda positions to block their escape to Pakistan. ‘We need Rangers now!’ he radioed repeatedly. ‘The opportunity to get bin Laden and his men is slipping away!’ But the answer came back, no, it should be left to the Afghans. ‘The generals were afraid of casualties!’ said Berntsen, still incredulous. ‘Yet these guys had just killed 3,000 people in New York, and might do again. What kind of insanity is that, not sending troops?’

Only on 6 December, the eleventh day of the sixteen-day battle, did Delta Force arrive in Tora Bora and the military take control from the CIA. They set up base in an old schoolhouse, commanded by a major who uses the pseudonym ‘Dalton Fury’. Yet they numbered just forty – and to Berntsen’s wry amusement they had to pay bribes to their Afghan allies to be allowed through.

Because they were so few, the plan was to send the Afghan forces into the Tora Bora mountains to attack the al Qaeda positions from valleys on either side. The Americans would remain in observation posts, providing advice and air support, not lead the Afghans into battle or venture towards the forward lines.

For several days in early December, Fury’s troops moved up the mountains in pairs with fighters from the Afghan militias to set up observation posts. The Americans used GPS devices and laser range-finders to pinpoint caves and pockets of enemy fighters for the bombers. But the Delta Force units were unable to hold any high ground, because the Afghans insisted on retreating to their base at the bottom of the mountains each night, leaving the Americans alone inside al Qaeda territory. In a later official account the special forces said of Hazrat Ali’s forces, ‘[Their] fighting qualities proved remarkably poor.’11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Still, American aircraft were carrying out as many as a hundred airstrikes a day, and it was clear from what the US forces could see and what they were hearing in the intercepted conversations that the relentless bombing was taking its toll. A couple of times Berntsen even thought they had got bin Laden. Through the walkie-talkie they knew the al Qaeda fighters were running short of food and water, so they let them be resupplied by some local Afghans. The Afghans were paid to carry a GPS and press a button whenever they saw men or weapons. ‘We delivered food and water to them so we could get a GPS on bin Laden’s position then [on December 9] we dropped a Blu 82, the size of a car, and killed a whole lot.’

The 15,000-pound bomb, known as a daisy-cutter, was the largest bomb in the US inventory short of nuclear weapons, and was so huge it had to be rolled out the back of a C-130 cargo plane. It shook the mountains for miles. Before Afghanistan, the weapon had not been used since Vietnam, and to start with the Americans feared that it had made less impact than they expected. But then Fury heard al Qaeda fighters radioing for the ‘red truck to move wounded’, and frantic pleas from a fighter to his commander, saying, ‘Cave too hot, can’t reach others.’12 (#litres_trial_promo) A captured al Qaeda fighter who was there later told American interrogators that men deep in caves had been vaporised in what he called ‘a hideous explosion’.

Late afternoon the following day, 10 December, Hazrat Ali told the Americans that his men had bin Laden surrounded. But as the Americans set off up the mountain in six Toyotas, they came across Ali leaving in a convoy. He promised that he and his men would turn round at the bottom and return, but they never did. Frustrated, the Americans called in seventeen hours of continuous airstrikes.

Fury was astonished when next day Haji Zaman asked for a twelve-hour ceasefire, saying that al Qaeda wanted to come down from the mountains and surrender. Bin Laden was heard on the radio telling his men that he had let them down and it was OK to surrender. Fury hoped the battle was over as Zaman claimed, but he was suspicious. They agreed an overnight pause in bombing, but by the next day not one surrendering fighter had appeared. Fury would later believe the message was a ruse to allow al Qaeda fighters to slip out of Tora Bora for Pakistan. As many as eight hundred are thought to have left that night.

Yet bin Laden was still in Tora Bora, and it seems he expected to die there. A copy of his will was later found, written on 14 December 2001. ‘Allah commended to us that when death approaches any of us that we make a bequest to parents and next of kin and to Muslims as a whole,’ he wrote. ‘Allah bears witness that the love of jihad and death in the cause of Allah has dominated my life and the verses of the sword permeated every cell in my heart … and fight the pagans all together as they fight you all together.’ He instructed his wives not to remarry, and apologised to his children for devoting himself to jihad.

Berntsen kept warning everyone that they were losing the chance to get bin Laden, and needed to send troops to block off exits on the Pakistan side. But Major General Dailey said General Franks had refused, explaining that Rumsfeld wanted to keep the US presence to a ‘light footprint’, and he feared alienating their allies.

‘I don’t give a damn about offending our allies!’ Berntsen shouted. ‘I only care about eliminating al Qaeda and delivering bin Laden’s head in a box!’ Dailey said the military’s position was firm, and Berntsen replied, ‘Screw that!’

Back in Washington, Berntsen’s boss Hank Crumpton, head of Afghan strategy for the CIA Counter-Terrorism Center, went to see Bush at the White House and warned him, ‘We’re going to lose our prey if we’re not careful.’ He recommended that Marines or other US troops be rushed to Tora Bora.

‘How bad off are these Afghani forces, really?’ asked Bush. ‘Are they up to the job?’

‘Definitely not, Mr President,’ Crumpton replied. ‘Definitely not.’

Yet still no more troops were forthcoming. Fury recommended sending his men to the Pakistan side of the border, but was given the thumbs down. So desperate was he that he even suggested dropping landmines to blow up the al Qaeda fighters as they came out of the tunnels.

What none of them knew was that General Franks was already busy on Iraq plans.

On 15 December Berntsen’s men heard bin Laden on the radio again. The following day the al Qaeda leader is believed to have split his men into two and left with one group of two hundred Saudi and Yemeni bodyguards over the mountains to Parachinar in Pakistan’s tribal area, a strip of lawless land between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Bin Laden had been helped by Pakistanis and Afghans he had paid, some of whom were also being paid by the Americans.

Fury finally managed to persuade Hazrat Ali to keep his men in the mountains, and for the next three days they went from valley to valley, but there was no more resistance. Al Qaeda had disappeared. They found 250 dead. By 17 December Hazrat Ali declared the battle over.

That same day Berntsen left Afghanistan, frustrated beyond words. Back home with his wife and two children for Christmas, he was horrified when he switched on his television to see the bearded face of his tormentor: ‘I just kept thinking we could have had him.’

The Pakistani military were angered at the widespread perception that they had let bin Laden and his men through. General Ali Mohammad Jan Aurakzai, a friend of President Musharraf, had been appointed commander of the Frontier Corps shortly after 9/11. When the US started bombing Tora Bora on 8 December, he got a call from Pakistan’s Director General of Military Operations. ‘He asked me about the possibility of sending troops into the tribal agencies of Khyber and Kurram, as there was a possibility of bad guys coming over the border from Afghanistan. I didn’t think it was a good idea, as we had no government presence, no police, no intelligence in those areas …’

Coming from the tribal areas himself, he knew it would upset decades of delicate balance since the days of the Raj. The British had found the only way to deal with the Pashtun tribes along the frontier was by stick and carrot, giving subsidies to their chiefs or ‘maliks’ and putting in representatives called Political Agents who could impose collective punishment on the whole village or tribe for any misdemeanour.13 (#litres_trial_promo) As long as the tribes stayed quiet, government would stay out of their affairs. The idea was they would serve as a buffer or ‘prickly hedge’ to guard the entrance to British India.

When Pakistan was created in 1947 this policy continued and these so-called tribal areas were left semi-autonomous, with federal control extending only a hundred yards either side of the road. The Pakistan army had never entered these areas, yet would now be doing so at the behest of kafir foreigners and against one of the key tribal principles of melmastia – providing hospitality to a guest or those who come looking for sanctuary (which of course also made it the perfect hiding place).

General Aurakzai feared this could spark a tribal uprising. ‘But the Americans said if we didn’t do it, there was the possibility of hot pursuit, which would have been humiliating for us, so I said we must act. It was also an opportunity to open up these inaccessible areas. We spoke to the local tribesmen and said either you allow in Pakistani troops or you will have US troops and aerial bombing, which they were very averse to. So they promised full support, as long as we were not a permanent presence, and told us they would not harbour foreign terrorists. Three days later, on 11 December, we dropped troops on the passes. There was no road, so the main body had to go on foot and equipment carried on mules. Within ten days we had arrested 240 al Qaeda and killed ten. We lost seven of our own men. It was all going well. But then unfortunately India mobilised its forces on our eastern border [in reaction to an attack on its parliament] and we had to decide what to do as we couldn’t be in both places.’14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Berntsen was convinced that had Bush not refused the request for more soldiers, the al Qaeda leader would have been killed at Tora Bora instead of becoming a recruiting tool for jihadis, and the world would have been a different place. ‘There isn’t a day when I don’t think “If only”,’ he told me. ‘We didn’t need much more. If we’d had six to eight hundred men we could have finished the job. Afghanistan was a flawed masterpiece.’

In 2009 a Senate report chaired by Senator John Kerry on what happened at Tora Bora would reach the same conclusion: ‘The failure to finish the job represents a lost opportunity that forever altered the course of the conflict in Afghanistan and the future of international terrorism, leaving the American people more vulnerable to terrorism, laying the foundation for today’s protracted Afghan insurgency and inflaming the internal strife now endangering Pakistan.’

In Jalalabad I went to see one of the three main commanders to whom the Americans had contracted out the fight, to hear his version of events.

Haji Abdul Zahir was the closest thing Afghanistan had to mujaheddin aristocracy. He was the nephew of the late Abdul Haq and the son of Haji Qadir, who had also been a commander, and was one of five Vice Presidents to Karzai and one of the few Pashtuns in the administration. In July 2002 Haji Qadir was assassinated by gunmen as he left his office in Kabul, his truck riddled with thirty-six bullets.

Haji Zahir’s house was a study in warlord chic. A golden chandelier dominated the marble entrance hall, and a sweeping staircase led up to a balcony with a billiards table. Everywhere there were blown-up photographs of himself and his late father and uncle. He was waiting for me, lounging on cushions on a raised platform beneath a gilt-framed oil painting of his father with an Afghan flag.

A servant brought us glasses of fresh pomegranate juice and small bowls of almonds and pistachios, and Zahir’s personal cameraman appeared to record the interview. But Zahir’s words were drowned out by what I thought at first was screaming, but which he explained was the sound of birds.

‘I keep hundreds of birds,’ he said. ‘I love birds.’ I presumed he meant fighting birds – a tradition in a country where just about every hobby involves fighting – but he looked pained when I asked. ‘Not fighting birds,’ he pouted. ‘I like them singing, it’s very sweet.’15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Somebody was dispatched to take out the birds, and he began to talk about Tora Bora, using floor cushions to illustrate the topography. ‘From the beginning the mission was not strong enough and the plan was weak,’ he said. ‘If you have enemies on this pillow and you don’t surround it, then they will run away. So without any plan the planes were flying and bombing, but the ways were open so of course they ran away.’

Like Berntsen, he had no doubt that bin Laden was there. ‘I myself caught twenty-one al Qaeda prisoners, some from Yemen, Kuwait, Saudi and Chechnya. One was a boy called Abu Bakr, and I asked him when he had last seen bin Laden. He said ten days earlier bin Laden had come to his checkpoint and sat with them for twenty minutes and drank tea and said, “Don’t worry, don’t lose morale, we’ll be successful and I am here.”’