По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

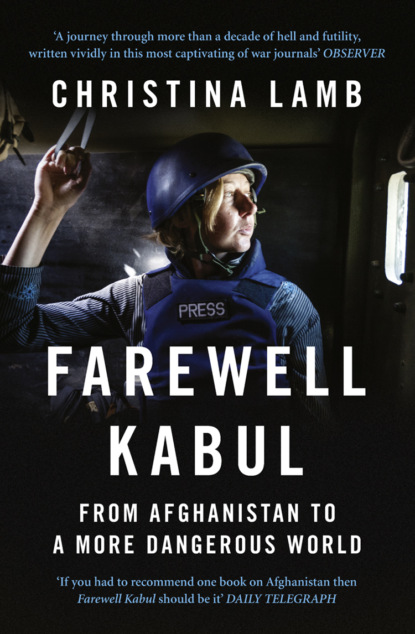

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Number of NYPD officers killed: 23

Number of Port Authority police officers killed: 37

Number of WTC companies that lost people: 60

Number of employees who died in Tower 1: 1,402

Number of employees who died in Tower 2: 614

Number of employees lost at Cantor Fitzgerald: 658

Number of nations whose citizens were killed in the attacks: 115

Number of Jews killed: estimated between 400 and 500

Ratio of men to women who died: 3:1

Bodies found ‘intact’: 289

5

Losing bin Laden – the Not So Great Escape (#ue110efdd-99ae-5c21-ae82-f889fc3c445e)

A few weeks later, Hamid Karzai also visited the ruins of the Twin Towers, and laid a wreath of yellow roses. He had been invited to America to be President Bush’s special guest at the annual State of the Union speech to Congress in Washington DC. Also invited were the two American Airlines hostesses who had managed to pin down Richard Reid, the shoe bomber. It was Karzai, however, in the long striped coat that he now wore everywhere, who was the star of the occasion, nodding and smiling as he received a standing ovation from the assembled Congressmen and Senators. The man who just six months earlier couldn’t get a meeting in this city was suddenly the toast of the entire Western world. The press was effusive. Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times called him the ‘caped hero’, while in an editorial in the Washington Post, Mary McGrory described Karzai as the ‘role-model US-installed leader of Afghanistan. He is, in fact, a dream.’ He’d even been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Bush was also enjoying an astonishing approval rating of 80 per cent following the quick demise of the Taliban, and his speech that night was triumphant. ‘In four short months, our nation has comforted the victims, begun to rebuild New York and the Pentagon, rallied a great coalition, captured, arrested, and rid the world of thousands of terrorists, destroyed Afghanistan’s terrorist training camps, saved a people from starvation, and freed a country from brutal oppression.’ This boast was greeted by wild clapping – his forty-eight-minute speech was interrupted by applause seventy-six times. However, there was one thing missing. What the US hadn’t done was track down Osama bin Laden, the man because of whom they had invaded Afghanistan.

Instead they had managed to lose him completely. While I had been back home in London for Christmas, bin Laden had released another video that was clearly designed to taunt the US. Dressed in a combat jacket, with a Kalashnikov propped up next to him, he described his thirty-three-minute-long message as a review of events following 9/11, which he referred to as ‘the blessed strikes against world atheism and its leader, America’.1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Later we’d find out that US forces had come within two miles of catching him less than two weeks earlier in the mountains between Afghanistan and Pakistan, but he had escaped over the border. It would be some years before I properly pieced together the story of what some called the greatest military blunder in recent US history.

On paper, finding bin Laden didn’t look hard. The FBI Most Wanted page described the al Qaeda leader as between six foot four and six foot six tall, about 160 pounds, olive complexion, left-handed and walking with a cane. His bony, bearded face and lanky frame were distinctive and easily recognisable from his videos. He was also rumoured to be suffering from kidney disease and requiring dialysis, though his son Omar would later dismiss this, explaining that it was kidney stones.2 (#litres_trial_promo) And there was a $25 million reward on his head.

‘I don’t want bin Laden and his thugs captured. I want them dead,’ Cofer Black, head of the CIA’s Counter Terrorism Center, had told his agent Gary Schroen as he set off with the first team for Afghanistan on 19 September.3 (#litres_trial_promo) In case there were any doubt about its intent, their operation had been codenamed ‘Jawbreaker’.

Shortly after the fall of Kabul on 13 November 2001, reports started coming in that bin Laden and as many as a thousand of his followers were in hiding a few hours south of the capital, in the mountainous area of Tora Bora not far from Jalalabad.

I’d been to Tora Bora in the 1980s during the jihad against the Russians, and it was really just a series of caves made by rainwater dissolving the limestone in the Spin Ghar, the White Mountains that run between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Bin Laden and his Arab followers had realised that the forbidding terrain of narrow stony valleys and jagged peaks reaching 14,000 feet turned it into a natural fortress, and had used dynamite to extend the caves.

The mujaheddin I was travelling with at the time told me to hide my face as we came to a place called Jaji and passed the entrance to a cave cloaked with camouflage netting and guarded by fierce-looking men with dark skin, some of them apparently African. ‘Arabs,’ they whispered. ‘They are crazy dangerous.’

The Afghans did not like the Arabs, who they felt looked down on them. ‘They called us ajam – people with no tongue – because we pray in a language we can’t understand [Arabic],’ Karzai’s elder brother Mehmud told me.

I’d never heard of bin Laden then. But later, in Peshawar, I would hear stories of the young Saudi millionaire who was bringing in bulldozers and dynamite from his father’s construction company and even an engineer to blast a network of tunnels in the caves so his fighters could move unseen in the mountains. His propaganda headquarters and guesthouse in Peshawar for Arab volunteers, the ‘Services Bureau’, was actually just along the road from the American Club where we foreign journalists used to gather at night for Budweisers and Sloppy Joes.

The Bureau had been set up in 1984 by a man called Sheikh Abdullah Azzam, a charismatic Palestinian cleric whose book Defense of the Muslim Lands compared Afghanistan to a drowning child that everyone on the beach had the duty to try to save. He argued that if even just one metre of Islamic land had been occupied by kuffar or infidels, then all able-bodied Muslims should strive to liberate it. The foreword was written by Saudi Arabia’s chief cleric, which seemed to give the book official sanction.

Azzam had studied at al-Azhar University in Cairo, which was the centre of Islamic scholarship in the Middle East, and he cut a distinctive figure with his black beard streaked with lightning forks of white, and round his neck the keffiyeh, the black-and-white-checked scarf favoured by Palestinian resistance fighters. In 1981 he took a job teaching Islam in the International Islamic University in Islamabad, and began spending every weekend in Peshawar where he met many Afghans fleeing the Russians or injured in bombings, and became passionate about their cause.

Among those inspired by Azzam’s writings was a twenty-four-year-old Algerian imam who went by the name of Abdullah Anas. Brought up on stories of the long war for Algeria’s independence from France in which his father and grandfather had fought, he’d joined the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist socio-political movement founded in Egypt, and thought his turn had come to take up his gun for a cause.

He flew to Mecca in 1984 to meet Azzam, who invited him to visit him in Islamabad. On his first night there, at dinner at Azzam’s house, Anas was so mesmerised by his host that he barely noticed another guest, recalling only that he was ‘very shy’ and had a ‘soft voice and handshake’.4 (#litres_trial_promo) It was Osama bin Laden.

Azzam talked that night, as he often did, of his frustration at the demise of the Muslim world, expounding on how back when Europe was in its Dark Ages, the rule of the Caliphates stretched from China to Spain, and it was a time of great innovation. Islamic scientists and mathematicians produced the first studies on optics and blood circulation, devised algebra, and invented astrolabes, Al Jaziri’s elephant clock and even an early flying machine (which crashed). But seven centuries of expansion came to an abrupt end in 1492 when Granada fell with the capture of the Alhambra by Christians, an event celebrated in London’s St Paul’s Cathedral with the singing of the Te Deum, a hymn of thanks.

In the same way that Americans regarded Afghanistan as a Cold War battleground on which to fight the forces of communism, Azzam saw in Afghanistan, with its simple brave men fighting a mighty mechanised army, a way of motivating a billion Muslims across the world and the first step to recapturing past glory and all former Muslim lands.

Galvanised by Azzam’s words, Anas travelled to Peshawar and joined some mujaheddin, with whom he walked for forty days across war-torn Afghanistan. It was so hard that he lost most of his toenails, but he said afterwards: ‘I felt I was reborn when I first got there … Even though I was sick for ten days, I was so happy to be walking along with my Kalashnikov and with my brothers.’

He decided to stay in Peshawar. He married Azzam’s daughter and helped him establish the Makhtab-al-Khidamat (MK), or the Services Bureau. Bin Laden had also decided to stay, and provided much of their funding as his father owned the biggest construction company in Saudi Arabia, estimated to be worth $5 billion, and gave him a yearly stipend of at least $7 million.

Right from the start the three men realised the importance of propaganda, and from those headquarters they produced a magazine called al-Jihad. Initially a few black-and-white pages crudely stapled together, it grew into a full-colour glossy with a circulation of 70,000 throughout Muslim communities across the world. Many were distributed in the United States, where the MK established a string of offices with a headquarters in Brooklyn.

In Washington at that time a Texan Congressman, Charlie Wilson, was pounding the corridors of the Capitol extolling the bravery of Afghan ‘illiterate shepherds and tribesmen fighting with stones’ in order to persuade his colleagues to commit more funds. ‘I had everyone in Congress convinced that the mujahideen were a cause only slightly below Christianity,’ he said.5 (#litres_trial_promo)

In the same way, in Muslim communities around the world, including in America, Azzam used his magazine and speeches to create the image of an almost mythical holy warrior. Those who heard him speak say he spellbound audiences with tales of flocks of birds that flew over Afghan villages to warn of approaching Soviet helicopters; of mujaheddin almost single-handedly defeating columns of Soviet tanks; and miracles such as fighters being hit by bullets yet magically not being wounded.

Such stories, combined with the idea of recapturing a glorious past, created a powerful message to frustrated young Arabs. To further motivate them they were told that if they died in jihad they would not only be rewarded with seventy-two virgins in the afterlife, but would also enable seventy family members to go to heaven. Azzam went on recruiting tours, exhorting young Arabs to ‘join the caravan’. Agents rounded up people, picking up recruiting bonuses for doing so. The bin Laden construction company acted as a pipeline, with Osama setting up a halfway house in Jeddah and providing a stipend to the families of fighters of $300 a month. Some were just tourists going off to jihad for a week, helped by generous discounts offered by Saudi Airlines. Others became committed jihadists.

Reception committees were set up at Pakistan’s main airports. One of the greeters was Dr Umar Farooq, who at the time was a medical student at King Edward College, Lahore, and whose family was regarded as a kind of Islamist aristocracy in Pakistan. His father had set up the country’s first madrassa, and his elder brother had built the first hospital for Afghan refugees in Quetta and married the daughter of the leader of Jamaat-e-Islami, Pakistan’s largest religious party.

‘Azzam was very impressive,’ he said. ‘Whoever met him became a mujahid. I would receive the Arabs at the airport. To start with they were good people, Egyptians, Yemenis, Saudis, Kuwaitis, Sudanese, Moroccans … I gave them maps with arrows pointing to show Soviet forces heading toward the Warm Water and we would send them to Peshawar and Quetta to our reception centres from where they would be sent to all the [mujaheddin] parties.’6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Not all came to fight. The Services Bureau provided schooling, clinics and refugee care as well as running an active propaganda division. But most came for jihad, and Azzam thought these Arab fighters should be scattered throughout Afghan groups to motivate them and teach them about Islam. The majority were sent to join Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, one of the seven Afghan mujaheddin leaders, who like Azzam was a graduate of al-Azhar and a Wahhabi. Sayyaf was very close to the Saudis, in particular the intelligence chief Prince Turki al Faisal. Not only did the Saudis provide the mujaheddin with $500 million every year, that went to a Swiss bank account controlled by the US and distributed to ISI, but Prince Turki’s chief of staff Adeeb (who had once been bin Laden’s biology teacher) visited Peshawar twice a month with cash for the leaders.

After a while Dr Farooq noticed a change. ‘Initially the Arabs went to different groups but then they started to be diverted all one way to promote the Saudi kind of Islam, Wahhabism, and all went to near Jalalabad. Different sorts of people started coming, criminal people who grew these long beards.’

Many were fugitives, some of whom had been involved in radical Islamic movements at home. Countries such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia were only too happy to get rid of such people. In Peshawar they would adopt a new identity – often being known by where they came from, such as ‘al Libbi’ – the Libyan.

Milt Bearden, who was CIA station chief in Pakistan at the time, later admitted that many were criminals. ‘Egypt and many other Islamic nations found Afghanistan a convenient dumping ground for home-grown troublemakers. Egypt quietly emptied its prisons of its political activists and psychotics and sent them off to the war in Afghanistan with fondest hopes that they might never return.’

Both ISI and the Americans thought it was a good idea to broaden the cause, and turned a blind eye to the backgrounds of these additional fighters. ‘All we cared about then was defeating the Soviets,’ admitted Richard Armitage, then the Under-Secretary of Defense. ‘We weren’t thinking about Osama bin Laden. Who cared what happened in Afghanistan? We had a much greater objective. Our Afghan policy was amoral in my view,’ he added. ‘Not immoral but amoral. We had one objective, and we didn’t care what happened after that.’7 (#litres_trial_promo)

General Hamid Gul, who headed ISI from 1987 to 1989, estimated that around 3–4,000 Arabs came to join the fight. ‘The Pakistan government never objected to them coming,’ he said. ‘Princes used to come and go inside [Afghanistan] from all over the Middle East for jihad, and this was just an extension.’

Though General Gul would send his officers to talk to bin Laden, he says he never met him when he was living in Peshawar. ‘I only met him in Sudan in ’93 and ’94 when I was invited by him. Before that I used to hear about Osama from CIA officers – they used to admire him, romanticise him, they seemed enamoured of him.’

From 1985 bin Laden started spending less time fundraising at home in Saudi Arabia and more time inside Afghanistan. When he did go home to Medina, he spent his time studying military maps. ‘I hated the Russians because they took my father away from me,’ his fourth son Omar later wrote.8 (#litres_trial_promo) One day the five-year-old Omar tried to get his father’s attention by dancing round the maps. Bin Laden was so enraged that he summoned his older sons and caned them all for allowing Omar to disturb his work.

Inside Afghanistan, bin Laden worked closely with Jalaluddin Haqqani, a powerful commander based near the south-eastern city of Khost who had become something of a folk hero. But increasingly he became convinced that what was needed was his own Arab force, rather than dispersing the Arabs among the Afghans as Azzam advocated. In 1986 a mujaheddin leader called Yunus Khalis, who was also close to Haqqani, agreed to let bin Laden set up his own camp in an area under his control. Bin Laden chose Jaji in the Tora Bora mountains, and named it al Masada, ‘the Lion’s Den’, after his own name, which meant lion.

To the Afghans it seemed an odd choice. The camp was on a pine-clad mountain and very near a Soviet base – ‘almost as if they wanted to be seen’, said Khalid Khwaja, an ISI officer who went there in 1987. For four months of the year it was cut off by snow.

Accompanying bin Laden were fifty or sixty of his most fanatical followers – mostly Saudis but also Yemenis and Sudanese. In key positions he had two former Egyptian policemen: his military commander Abu Ubaidah, whose brother had been involved in the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, and his deputy Abu Hafs.

After some initial humiliations the first major engagement of these ‘Arab Afghans’ came in April 1987 when they were bombed by the Russians in what became known as the Battle of Jaji. Accounts vary of whether the bombing went on for one week or three, but Osama and his men stood their ground, even against the feared Spetsnaz, or special forces, and later claimed to have shot down one of their Hind helicopter gunships.

The stories of Jaji became legendary, and led to many young Arabs wanting to join bin Laden. The once shy young man became more assertive, producing his first promotional videos. These showed him on the back of a white horse, a deliberate reference to the Prophet on his white-winged horse Burak, as well as speaking on a walkie-talkie and firing off Kalashnikovs. The tall, lanky millionaire who had given up his privileged life to fight with the Afghans became a Saudi hero. ‘He’d give you the clothes off his back,’ said Anas.