По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

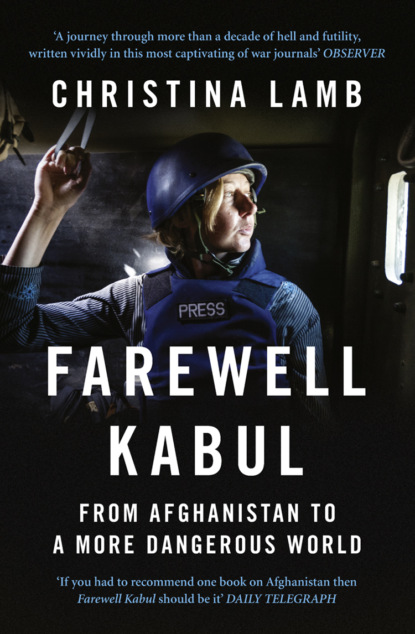

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Quetta, February 2002

The Additional Secretary Home and Tribal Affairs for Baluchistan was fed up. ‘Look at all these files, it’s rubbish!’ he barked. ‘This whole building is filled with rubbish!’

I could hardly disagree. Every available surface was covered with tottering piles of dusty files spewing out yellowing papers, and from adjoining offices came the sound of clattering typewriters churning out more. A stream of men wandered in and out, bringing files back and forth containing carbon-copied letters to be signed and placed in other files.

‘You people did this,’ he said, waving his hands. In fact, I suspected things hadn’t really changed since colonial days, though I wasn’t sure if he meant the bureaucracy, or if he was gesturing at the map on the wall. It was a large hand-drawn map of the region on which the land north of Afghanistan was marked ‘Russian Dominions’, while that to the west was ‘Caucasia’. Some parts had been shaded in different colours, and there was an explanatory key code at the bottom: Red = Tribes in Baluchistan; Blue = Pathan in Pakistan and Afghanistan; and, confusingly, Blue [though a slightly different blue] = Miscellaneous Tribes in Iran.

A gold-lettered wooden board over the Additional Secretary’s desk showed that no one stayed long in the post. Humayun Khan was the eleventh occupant in fourteen years, and that included several long periods for which the board was inscribed ‘Post Vacant’, as if that were a person’s name.

I was trying to get something called a No Objection Certificate (NOC) to permit me to travel through the tribal areas to the Afghan border, and he was the only person who could grant one. However, he had a thick blue file which he explained was on me. ‘What are these “undesirable activities”?’ he asked, leafing through it. ‘You are a terror! More, more undesirable activities,’ he intoned. ‘Undesirable activities, I suppose they are one of the great indefinables, like national interest or supreme national interest. Frankly, Mrs Lamb, I am surprised you are back in Baluchistan.’

So was I. It was less than ten weeks since my previous stay had come to an abrupt halt when I’d been woken up by ISI banging on the door of my room in the Serena Hotel at 2 a.m. Probably the last place on earth I wanted to be was back in Quetta, particularly on my own. However, I had spent the previous few weeks in Kandahar, where I learned that when the Taliban surrendered this, their final stronghold, without a shot on 7 December 2001, they had fled to the Pakistan border in their thousands. There they were met by ISI officials and Frontier Constabulary who shepherded them to camps, madrassas or houses in a suburb of Quetta known as Satellite Town, and told them to lay low. The B52s may have driven the Taliban out of Afghanistan in less than sixty days, but in their view they had only lost the battle, not the war.

Among them were most of the leadership, who would come to be known as the Quetta shura. My friend Dr Umar, who used to run reception committees for Arabs coming to fight in the jihad, had close connections with senior Taliban. He offered to take me for tea with some of the ministers, and I had no intention of passing up the chance. The problem was how to do it without being caught by ISI. The agency received a list of every foreigner who flew into Quetta or checked into any of the few hotels, and as a tall, blonde Englishwoman, if I took the bus from Karachi I would be very conspicuous.

My plan was to go to Quetta openly, stating that I was on my way to Kandahar, just over the border. This would also give me a chance to talk to people in the frontier towns of Chaman and Spin Boldak. I would cross over legally, then sneak back into Pakistan using the old mujaheddin trails. ISI would assume I was in Afghanistan.

It wasn’t a great plan, and frankly I was terrified. It also depended on me getting an NOC, and this depended on the crotchety Additional Secretary. A series of phone calls got me nowhere, and I had been forced to check back into the Serena.

I didn’t get much sleep, for there was a picture I couldn’t get out of my head. Two weeks earlier, on 23 January 2002, an American reporter named Daniel Pearl from the Wall Street Journal had been kidnapped in Karachi while investigating links between militant groups and Richard Reid, the British shoe bomber. Just before I travelled to Quetta an email had been sent to news organisations with photos of a frightened Pearl in shackles with a gun to his head, and a warning for all American journalists in Pakistan to leave within three days.

The sender was the ‘National Movement for the Restoration of Pakistani Sovereignty’, a group that nobody had heard of, and they seemed to have strange demands. Apart from the release of 177 Pakistanis being held in Guantánamo, they were demanding the delivery of American F16 fighter jets purchased by Pakistan in 1989 but never handed over. I’d never heard of a terrorist group demanding F16 jets. However, anyone who had spent much time in Pakistan knew that the F16s are a national obsession. The issue was frequently raised in newspaper editorials, and the jets vied with Bollywood stars as the favourite thing to paint on the colourfully decorated Bedford trucks that transport goods around the country. Most of all they were an obsession of Pakistan’s powerful generals, for whom they were a festering sore in relations with Washington.

The issue went back to the late 1980s, when Pakistan and the US had been going through a good patch in relations (or at least shared a common interest), working together to train and arm the Afghan mujaheddin to oust the Russians. In 1989 Pakistan had ordered twenty-eight F16s from the American company General Dynamics for $22 million each. But in 1990, before the planes could be shipped, the sale was cancelled by Congress because of reports that US jets bought by the military ruler General Zia in 1983 had been modified to carry nuclear warheads. The departure of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan in 1989 meant the US was no longer prepared to turn a blind eye to Pakistan’s nuclear activities, and the F16s were sent to a facility in the Arizona desert known as ‘the boneyard’. Not only did the US refuse to reimburse the $656 million paid by Pakistan to American defence contractors, but to add insult to injury they also charged it for storage. The episode left Pakistan’s generals convinced that Americans couldn’t be trusted. They only got the money reimbursed by the Clinton administration a decade later after they hired former White House lawyer Lanny Davis. But really they wanted the planes.

‘It’s either ISI or someone wanting to make it look like ISI,’ said Umar when the kidnappers’ demands circulated.

Pakistan is a land of conspiracy. Everyone I met told me that ISI had encouraged the kidnapping of Pearl to discourage other foreign journalists from investigating the country’s murkier links. If that was so, they had been pretty successful. When I had last stayed in Quetta two months earlier, the Serena had been so packed with journalists that some were even paying to rent the laundry cupboard or to sleep on the floor of the ballroom. This time it was empty.

I had no intention of spending more time in Quetta than necessary. So that morning when I got into the Additional Secretary’s office, I was determined that I would not leave without the NOC in my hand.

It seemed clear that the real problem was that no one wanted to take responsibility. While the Additional Secretary was complaining to me, another carbon-copied letter came down from the section officer upstairs, this time on green paper. ‘Regarding Mrs Christina Lamb,’ it stated. ‘The NOC could be issued or otherwise.’

Mr Khan pushed it aside. ‘The only reason you Britishers are successful is because of the cold weather,’ he said. ‘I went to Britain once, to Brighton and Blackpool. It wasn’t worth it,’ he added dismissively.

I had no idea which way he was leaning, when suddenly he reached for his pen. ‘If no one else wants to take responsibility I suppose I’ll have to use my discretion,’ he said.

After a second near-sleepless night in the Serena, I couldn’t believe it when I woke the next morning to snow – the first in Quetta for fifteen years. Everyone in town was happy, because it meant the end of drought. I was worried the snow would trap me in the Serena for more sleepless nights, but Umar turned up as promised with his ambulance, in which we would travel to the border. ‘It’s good luck for your trip,’ he said, smiling. He may have spoken too soon. By the time we collected the guards assigned by Mr Khan’s office and headed towards the Khojak Pass, the snow was falling quite thickly, coating the hills and making the way treacherous.

The road to the border follows the railway from Quetta to the border town of Chaman, built by the British in the 1880s, after the Second Anglo–Afghan War. The railway was clearly intended to go into Afghanistan – to the fury of King Abdur Rahman, who described it as ‘like pushing a knife into my vitals’, and forbade his subjects from travelling on it. It is an incredible feat of engineering, snaking in and out of the pass via tunnels through the mountains, including the longest one in South Asia, which is commemorated on Pakistan’s five-rupee note.

Even without snow it is inhospitable terrain, and it was perhaps a Baluch idea of a joke to give the towns along the way inappropriate names. There is Gulistan, which means ‘place of flowers’ and has none; Fort Jilla, which has no fort; and Chaman, which means ‘fruit garden’, yet nothing grows there. Most poignant was Sheilabagh, supposedly named after the wife of the chief engineer. Apparently he’d made a bet with the engineer working from the other end of the line that the two tunnels would meet on a certain date. When they didn’t, he committed suicide. The tunnels met the next day.

As we climbed above Sheilabagh the ambulance wheels started slipping and sliding. Umar had no idea how to drive on ice, and kept braking. I tried not to look over the side of the pass, with its precipitous drop. When we finally managed to slip and slide further up the road, we found the way blocked by painted trucks, one heavily overloaded with logs and the other with bright-coloured cloths and mattresses spilling out. Men were shouting unhelpful advice and occasionally pushing.

I jumped out of the ambulance, causing everything to stop, foreign women being rare in these parts, when suddenly an army jeep drove up. Inside were two Pishin Scouts, members of one of the regiments of the paramilitary Frontier Corps originally set up by the British to control smuggling and the border. They got the trucks moved, and one of the officers, Captain Mubashar, gallantly came to my rescue. ‘I will take memsahib in my 4x4,’ he said.

On the way he told me they had spent the night before on foot patrol in the mountains, looking for al Qaeda. It was very difficult, and so far the Pishin Scouts had caught just four Arabs. ‘It’s a very long and porous border and they still have lots of money to pay locals,’ he explained. ‘What about Taliban?’ I asked. Had he seen them coming across the border when Kandahar fell? ‘They have switched from black turbans to white and are tricky to spot,’ he laughed.

Captain Mubashar told me that before 9/11 the Scouts’ main work was stopping smuggling. When I admired a particularly elaborate painted truck, jingling with chains, he said, ‘Behind the rose is a thorn.’ He explained that the intricate paintings and metalwork often hide cavities in which contraband is hidden – sometimes opium, but also imported Japanese electronics, or just cloth or fruit to avoid duty. Some trucks have as many as twenty cavities. ‘Once I saw a truck of goats which didn’t look right,’ he said. ‘The goats looked too tall.’ When he opened the truck he found it had a false floor, with a whole level below.

Captain Mubashar and his colleagues had been so successful in catching smugglers that the previous year they had sent 550 million rupees in duties and fines to the federal government. But the local tribesmen were furious, and revolted, blocking the road and killing three soldiers. ‘It’s the only industry,’ he explained. ‘There are no factories, and nothing grows, even the apple orchard dried up, so everyone smuggles, even children of five or six have contraband in their pockets.’ In the end they decided to turn a blind eye to the small stuff. But he admitted they had little success in intercepting drugs. ‘They are transported over the mountains on unmanned donkeys which are trained to be terrified of anyone dressed in dark clothes.’ The Frontier Corps wear charcoal shalwar kamiz. ‘They run like mad when we come.’

In Captain Mubashar’s view, the lack of alternative sources of income, combined with the area’s traditional hostility to foreigners and the Pashtunwali honour code, which means strangers must be protected, made it extremely unlikely that any local would cooperate in handing over Taliban or al Qaeda.

I heard the same in the scruffy border town of Chaman, where he left me with Nasibullah, the head of the levies, the local tribal force set up in British times. Nasibullah was sitting in a room with walls painted baby pink with a bottle-green stripe all the way round and dominated by a vast Sony TV which looked suspiciously like the smuggled goods in the trucks we had passed. Around him, their eyes glued to the screen, was a gaggle of men with orange henna-stained beards. Also on the wall were three gilt-framed black-and-white photographs – Nasibullah’s late grandfather, first head of the levies; his father, who came next; and himself. ‘You Britishers created us, then left us orphans,’ he said.

Pashtun hospitality dictates that no visitor can leave without food, however much of a hurry they might be in. A servant laid a plastic cloth on the floor then brought in huge, steaming bowls of fatty lamb and a foot-long strip of stretchy nan bread. A plastic jug of water and a dirty towel were passed around for us to wash and dry our hands. The men then began to tear off the bread and scoop up the meat, eating lustily, with loud smacking noises. I tried to avoid the gristle and globules of fat, and to make it look as if I was eating more than I was, something I had perfected after years of practice.

Nasibullah told me that his uncle was head of the Achakzai, one of the tribes that straddles the border. I asked if they thought of themselves as Pakistanis or Afghans. ‘We’ve been Pashtuns 5,000 years, Muslims 1,400 years, then Pakistanis just fifty years,’ he replied. ‘You Britishers with your Colonel Durand divided our tribe. The real Afghan border should be a hundred kilometres south of Quetta, not this fake line of Durand.’

He told me that his men had arrested three al Qaeda they had found being treated in the local hospital and taken them to the authorities in Quetta, but later heard they escaped. As for Taliban, he said that Abdul Razzaq, the Interior Minister, and other senior Taliban were sheltering in the local madrassa run by Abdul Ghani, deputy to Maulana Fazlur Rehman, head of one of Pakistan’s main religious parties, Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JuI).

What about Osama bin Laden? ‘As long as he stays in our tribal areas he will not be found, because he is protected by Pashtunwali,’ he replied. But the Americans had announced a $25 million reward. Wouldn’t that tempt people? I asked. ‘That doesn’t matter, because most people think he was fighting for Islam,’ he said. ‘Anyway, it’s too much money. Nobody here understands what that means. They would have been better off offering a herd of goats.’

The last few miles to the border were full of people selling things by the wayside. An old man with an emerald-green turban and a long white beard was crouched on his haunches the way Pashtuns seem to be able to sit all day, with a cockerel in each hand like balancing scales.

It was almost dark when I finally reached the border post. There was a stream of bearded men blatantly walking to one side of it rather than through. Inside, a white-haired man was sitting at a desk. He looked relieved to see me. ‘Ah, Christina Lamb, I have been waiting for you,’ he said, unfolding a typed carbon copy, headed ‘Deletion of Mrs Christina Lamb from Exit Control List’. ‘I was worried you would slip over my border and I would lose my job of twenty years.’

The first thing that went wrong with my plan to sneak back into Quetta was that the new border office in Spin Boldak on the Afghan side tried to take all my money in bribes. The passport office consisted of a group of men lounging on cushions in a smoky room, drinking green tea and inventing ways to extract money from the few people who passed through legally.

‘$200 by order of the Governor for security,’ demanded one of them.

‘I don’t need security,’ I replied.

‘It is not a choice.’

‘$200 for a car,’ came next.

‘I’ve already got a car,’ I protested.

‘It’s for the security guards,’ was the reply.

‘Also $50 entry fee by order of the Foreign Ministry.’

‘I already have a visa,’ I pointed out.

‘That’s for Afghanistan, not for Kandahar.’

‘I’m a journalist, and this is not giving a very good impression of the new Afghanistan,’ I said in exasperation.

This prompted some heated Pashto discussion which I could not follow, but I assumed they were reassessing their extortion. I was wrong.

‘Journalist. $100 for press,’ said one of the men. ‘If you have camera and phone there will be more charges.’

‘What? Where is this written?’ I began to lose patience. ‘Look, I’m a friend of President Hamid Karzai, and I don’t think he would be very happy you are making up all these charges.’

They laughed heartily. ‘Karzai, who is he?’ said one.