По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

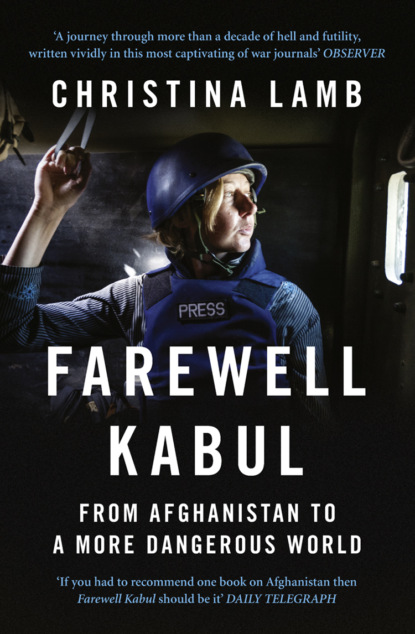

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Zahir went to join the fight after he switched on CNN one evening and saw an interview with his rival commanders Hazrat Ali and Haji Zaman. ‘They were saying they were in Tora Bora with 3,000 soldiers. Then General Ali called me and asked, “Why aren’t you here?” I said, “We can’t just go without any plan,” but then I spoke to my father who was at the Bonn Conference [to choose the interim Afghan government] and he said, “This is our fight, so prepare your things and go.” I got 1,100–1,200 men ready, and we arrived there at night. The first shock was that Hazrat Ali and Haji Zaman had boasted on CNN they had all these men, but in fact there weren’t even four or five hundred. They were just telling the Americans they had more to get more money.’

They had a meeting, and divided the area into three. Haji Zaman was to be in charge of Wazir valley, General Ali in charge of Milawa where bin Laden’s refuge was, and Zahir in charge of Tora Bora and Girikhel village. According to Zahir, Ali was being directed by the Americans while Zaman was liaising with the British. ‘There was a lot of money floating around. The US were paying $100–150 per day for each soldier, and the others claimed they had 3–5,000 men. I didn’t receive anything from them, not one gun, one bullet, one dollar. I spent $40,000 of my own money.’ (Later I would meet Hazrat Ali, who said Zahir had got the same as them.)

After a day of preparation they all set off up the mountains to their areas. By then the bombing of the encampment at Milawa had started. The plan had been to attack al Qaeda from the Wazir valley side, to trap them as the special forces wanted. Then, on 11 December, the evening the attack was due, Zaman, whose men were that side, said that al Qaeda had sent a radio message asking to be given till 8 o’clock the following morning, when they would surrender.

‘I didn’t agree,’ said Zahir. ‘I said, if they want to surrender, why not today? They’re the enemy – why are we giving them twelve hours to run away?’ But Zaman replied that they needed time to get in contact with each other, and halted the advance of his troops.

Zahir believed that Zaman had been bribed to let them disappear over the passes, and was convinced that the majority escaped. ‘Supposedly there were six to eight hundred people,’ he said. ‘I captured twenty-one. Ali and Zaman got nine. Dead bodies were not easy to count, but around 150. That means at least four to six hundred got away. For all that money spent and energy and bombing, only thirty were caught.’

To this day he remains mystified by the Americans. ‘Why weren’t there more Americans in Tora Bora?’ he asked. ‘Even after Delta Force arrived, they weren’t more than fifty or sixty. Believe me, there were more journalists than soldiers. It would have been easy to get bin Laden there. I don’t know why there was no plan to block the passes.’ He dismissed General Aurakzai’s claim that Pakistan had apprehended people on its side of the border. ‘What happened to those people? Aurakzai’s men were helping them move west to Waziristan.’

Mike Scheuer, who headed the CIA’s Osama bin Laden Unit from 1996 to 1999, and then became its special adviser from 2001 to 2004, probably knew more about bin Laden than any other Westerner alive. He was on the receiving end in Washington of many of the cables from Tora Bora. ‘It’s like many things in your life,’ he said. ‘If you don’t do something when you have the chance, sometimes that chance doesn’t come back.’16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Though he was frustrated by losing bin Laden at Tora Bora, he pointed out that the US had already squandered ten different opportunities to get their man back in 1998 and 1999. President Clinton had signed a secret presidential directive in 1998 authorising the CIA to kill bin Laden after al Qaeda bombed the American Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing more than two hundred people. But when it came to it, said Scheuer, Clinton did not have the necessary resolve: ‘Clinton was worried about European opinion. He didn’t want to shoot and miss and have to explain a lot of innocent deaths. Yet the very same day [in 1999] we turned down one opportunity to kill bin Laden, our planes were dropping thousands of bombs on the Serbs from 20,000 feet. The Serbs never did anything to us.’

On one occasion that same year, the US had live video pictures of bin Laden coming in from a Predator spy plane, the only time he was actually seen. ‘But the drone wasn’t armed at that time, because the fools in Washington were arguing over which agency should fund the $2 million installation of the Hellfire missile. It’s a very upsetting business. I got into a slanging match with Clinton on TV because he claimed that he never turned down the opportunity to kill bin Laden. That’s a very clear lie, and we’re all paying the price. Similarly at Tora Bora, our generals didn’t want to lose a lot of our soldiers going after him. They had seen what had happened to the Russians, who lost 15,000 men in Afghanistan. So it was easier to subcontract to Hazrat Ali, Haji Zahir and Haji Zaman. At the time we said, “Look, these guys are going to be a day late and a dollar short.” But they wouldn’t listen.’

Although some of the CIA officers involved later blamed the fiasco on infighting between the CIA and the military, Scheuer insisted that responsibility also lay with George Tenet, the CIA Director at the time. ‘Part of it was Mr Tenet’s fault, because he told the President, Rumsfeld and Powell that all you have to do is spend a lot of money in Afghanistan. Everyone who was cognisant of how Afghan operations worked would have told Tenet that he was nuts. During our covert help to the mujaheddin in the fight against the Russians, we spent $6 billion between us and the Saudis, and I can’t remember a single time the Afghans did anything we wanted them to do. The people we bought, the people Mr Tenet said we would own, let Osama bin Laden escape from Tora Bora into Pakistan.’

I wanted to see for myself the tunnels from which he had escaped, so I went to see the local Governor, Gul Agha Sherzai. ‘Tora Bora is already a world-famous name, but we want it to be known for tourism, not terrorism,’ he said. ‘Long before anyone had heard of Osama, Tora Bora was known as a picnic spot, and now it can be both.’ He showed me plans he’d had drawn up for a $10 million hotel development overlooking the caves. He also intended to build restaurants and to pave the road built by bin Laden leading to the mountains from Jalalabad. ‘I don’t just want one Tora Bora hotel,’ he said. ‘I want three or four!’17 (#litres_trial_promo)

The next morning, the chowkidar of the aid-agency guesthouse where I was staying hammered on my door in terror. ‘Gunmen are asking for you,’ he said. Outside were a police jeep and two pick-ups full of men with Kalashnikovs, one of whom introduced himself as Commander Lalalai, a famous old mujahid from Spin Boldak. As Tora Bora ‘wasn’t quite safe’ Governor Sherzai had sent these guards to accompany me. I climbed into the jeep and we sped off through the streets of Jalalabad, scattering donkey carts and turbaned men on bicycles. Eventually we turned off on an unmade road towards the White Mountains. ‘Tora Bora,’ said the driver, Mahmood, rolling his eyes.

On either side of the track were mud-walled compounds, one of which had an actual-size model of a car on its roof. Every so often Mahmood put on a terrifying burst of speed, throwing up so much dust that we could see nothing, and I would grip the door handle. ‘Al Qaeda, al Qaeda!’ he explained. Occasionally the truck in front would screech to a halt, and Commander Lalalai would jump out and start berating Mahmood for not going fast enough, saying we could be killed by the ‘bad guys’. I began to wonder about the Governor’s plans for tourism.

After two hours we stopped at the schoolhouse that had been used by the CIA and then Delta Force as base camp during the battle for Tora Bora, and collected two more vehicles of guards. By then we had twenty-six gunmen. So much for travelling low-profile.

The road deteriorated from dust to rocky scree, making the journey even more bone-shaking. But the scenery was spectacular, swirled-toffee mountains as far as the eye could see, rising to black rock, all under a deep-blue sky. On one side of the road lay the passes to Parachinar and the tribal areas of Pakistan. Almost twenty years before I had crossed these mountains with mujaheddin coming to fight the Russians, riding a donkey laden with rockets and grenades that left my legs purple with bruises.

Eventually our convoy pulled up under a tree and everyone piled out. ‘Now we walk ten minutes,’ said Mahmood. I had spent enough time in Afghanistan to know to multiply any times and distances by three. Foolishly, I left my food and water in the jeep, as it was Ramadan fasting month, and I didn’t want to eat in front of the others, who must let nothing pass their lips until nightfall. It was a decision I would regret.

An hour later we were still climbing the stony track along a dry riverbed and scrambling up and down scree-covered slopes, breathless from the thinning oxygen. But the guards seemed happy. They held hands, posed for photographs and kept coming to me with little offerings – some lavender they had picked, spent ammunition cartridges, and pieces of pink quartz. Every so often we passed people with donkeys or small children bearing bundles of wood – the slopes all around had been denuded of trees. The women hurriedly pulled their shawls over their faces.

Finally we stopped. The guards pointed across the gorge, shouting, ‘Osama house! Osama house!’ At first I could see nothing, but then I just made out a few holes and ruins on the terraced slopes. We clambered across past a burned-out tank and over some large bomb craters, and came to the ruins of some mud-walled houses.

I realised that the reason I had not seen it at first was that the site of the last great showdown between US forces and al Qaeda was not at all what I was expecting. At the time newspapers had run detailed graphics of James Bond-style hi-tech cave systems with internal hydro-electric power plants from mountain streams, elevators, ventilation ducts, loading bays, caverns big enough for tanks and trucks, and brick-lined walls.

Where was the vast network of tunnels that led to Pakistan? All I could see among the ruins was a circular hole, about three feet high, that seemed to be an entrance. I walked in, cursing myself for not having brought my torch. One of the guards had a cigarette lighter which he flicked on and off, but it was soon clear that the tunnel did not extend very far. Some of the gunmen were nervous, and stayed by the entrance blocking what light there was and giggling as if Osama was suddenly going to appear.

A combination of Afghan scavengers and US and British intelligence had scoured the caves, and nothing remained to suggest their past purpose. In one of them an SAS team had found plans for al Qaeda’s next attack, in Singapore. CIA agents even scraped the sides of the cave for DNA in the hope of finding that they had killed bin Laden.

The ‘light footprint’ which had been such a success in toppling the Taliban with minimum American casualties had enabled the world’s most wanted man to escape the net. Though bin Laden would periodically release videos which CIA agents and geologists would scrutinise to try to identify an area, there would be no more confirmed sightings. The CIA team would start referring to him as ‘Elvis’. President Bush was left with the consolation argument that the al Qaeda leader and his deputy were fatally weakened, detached from their followers and unable to plan any new operations.

6

A Tale of Two Generals (#ue110efdd-99ae-5c21-ae82-f889fc3c445e)

Bin Laden may have vanished into the mountains of the tribal areas, but his bony, bearded face was hard to avoid in Rawalpindi, where it stared out from boxes of sweets and posters on sale in the labyrinthine bazaars just a couple of miles from President Musharraf’s house. Right from the start it wasn’t clear whose side Pakistan was really on.

Although Pakistan had been a nominal ally of the US since Pakistan’s creation in 1947, it had never really been a happy marriage. Pakistan had long been ambivalent about the United States, which had poured money and arms in when it needed something – such as help in training and arming the Afghan mujaheddin to fight the Russians during the Cold War – then was never there when Pakistan needed it, such as in its three wars against India.

I always found this combination of Pakistan’s desire to be an American ally with its widespread anti-Americanism confusing. ‘Pakistan’s problem,’ said Husain Haqqani while he was the country’s Ambassador in Washington, ‘is that it is trying to be Iran and South Korea at the same time.’

‘America needs Pakistan more than Pakistan needs America,’ Pakistan’s founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah insisted to American journalist Margaret Bourke-White in an interview for Life magazine just one month after the country was born.

At the time that was clearly ludicrous. And indeed, during his election campaign in 2000, George W. Bush had been asked the name of the President of Pakistan, and had no idea.

But 9/11 had changed everything. Pakistan knew the Taliban better than anyone, for it had helped create them. Afghanistan was a landlocked country most easily reachable through Pakistan with its sea ports and air connections, and the two countries shared a 1,600-mile border which split Pashtun tribes living on either side, who crossed back and forth freely.

The Americans would have found it almost impossible to mount their operation to topple the Taliban regime without Pakistan. ‘And they knew it,’ said Richard Armitage, who was Deputy Secretary of State at the time.

In his memoir, President Musharraf recounted that Colin Powell, the US Secretary of State, phoned him on the morning after 9/11 and warned: ‘You are either with us or against us.’1 (#litres_trial_promo)

The head of ISI, General Mahmood Ahmed, happened to be in Washington at the time, ironically to try to convince the CIA that the Taliban were ‘misunderstood’ and should be engaged with. On 9 September he had lunch with the Director of the CIA, George Tenet, who later wrote, ‘The guy was immovable when it came to the Taliban and al Qaeda. And bloodless too.’

The day after the attack, Mahmood was called in by Powell’s deputy Armitage. ‘It was clear he was pretty much an Islamist,’ said Armitage. ‘9/11 for Americans was a life-changing event, because we’d always been protected behind our two great oceans, unlike almost any other country in the world. Yet Mahmood started out trying to tell me, “You’ve got to understand about what our people feel.” I could see he didn’t get it.’2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Musharraf wrote in his memoir that Armitage had used the meeting to make ‘a shockingly barefaced threat’ to bomb Pakistan ‘into the Stone Age’ if Islamabad decided not to cooperate. Armitage, a big hulk of a man who admits he can be ‘fearsome’, insists he said no such thing. ‘I’d love to have been able to,’ he laughed. ‘I would have needed a cigarette afterwards. I had no such authority. But we did have very strong discussions.’

As a former soldier himself, who understood the importance of honour, he did something else. ‘I took Mahmood to my private office, the small room behind the ornate main office, and said, “I want to show you something.” I opened a box, and inside was this Star of Pakistan I’d been awarded. “You see this?” I said. “No American would accept this ever if Pakistan is found wanting in assisting us. Ever.”’

The message got through. Musharraf chose cooperation, but it was hardly enthusiastic. ‘I made a dispassionate military-style analysis of our options,’ he later wrote. ‘I war-gamed them [the US] as an adversary. The question was if we do not join them, can we confront them and withstand the onslaught. The answer was no, we could not … we could not endure a military confrontation with the US from any point of view.’

The first American official to meet with Musharraf after 9/11 was Wendy Chamberlin, the US Ambassador, who had only been in Pakistan two weeks. She’d met the President when she arrived in August, and he had told her his vision was to encourage foreign investment, and to do that he realised he needed to control domestic terrorism and the sectarian violence in Karachi. ‘He thought Pakistan was the battleground in the proxy war between the Wahhabis and the Iranians, but didn’t feel empowered or think he had the tools to really crack down,’ she said.3 (#litres_trial_promo)

When she went in to see him on the morning of 13 September, she did not mince words. ‘It was the first time anyone had said directly to him, “Are you with us or against us?” He wasn’t persuaded at first.’ ‘It’s an opportunity,’ she told him. ‘We can help you in ways which will empower you to help us against internal terrorists.’ Musharraf was unconvinced. ‘He didn’t buy it. We went over and over – I said you can expect things – lifting of sanctions, the resumption of military aid, spare parts, direct assistance, grant aid … He waffled and danced around, giving me this whole bunch of crap, and in the end I turned away and put my head down in my hands. My DCM [deputy] kept looking and asked, “Wendy, what’s wrong?” I said, “I haven’t heard what I need to tell my President, which is we support you unstintingly.” Only then did Musharraf agree.’

‘Very good,’ she replied in relief.

As she walked down the long corridor out of the palace she saw CNN reporter Tom Mintier and his crew waiting. ‘I thought, “Do I tell CNN before I tell my government?” and I thought, “Yes, I do, because then I lock Musharraf in” – I felt him waffling.’

That night Colin Powell called Musharraf and sealed the deal.

For the wily Musharraf this was his chance to transform his image on the world stage. Until then he had been seen as an international pariah, having seized power in a coup on 12 October 1999 and locked up the elected Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in the old Attock Fort.

He told anyone who would listen that Sharif had tried to kill him ‘and hundreds of innocent Pakistanis’. Musharraf had been in Sri Lanka attending a conference and playing some of his beloved golf when Sharif had clumsily tried to sack him as his army chief. Musharraf jumped on a PIA flight back to Karachi which Sharif then refused permission to land, even though the pilot said he had only twenty minutes of fuel left. With the plane circling over the Arabian Gulf the generals stepped in, took over the TV station, airport and key buildings, and arrested Sharif.

In Musharraf’s view he had done both his country and the world a favour. ‘Today we have reached a stage where our economy has crumbled, our credibility is lost, state institutions lie demolished,’ he said in an address to the nation late that first night. He suspended the constitution and disbanded parliament, but to try to make the situation seem less coup-like, he did not take the usual title of Chief Martial Law Administrator. Instead he called himself ‘chief executive’, as if Pakistan were a business. Just like previous military rulers, he insisted: ‘The armed forces have no intention to stay in charge any longer than is absolutely necessary to pave the way for true democracy.’ In the case of his predecessor Zia-ul-Haq that meant staying eleven and a half years.

I was in the country within days of the coup, and it was clear that it was widely welcomed, people handing out sweets to celebrate. Pakistanis generally viewed their politicians as corrupt and incompetent, while the army is the only really respected national institution, despite having lost every war it has fought.

I went to see Musharraf in the white-colonnaded Army House with neat rose gardens where eleven years earlier I had interviewed Pakistan’s last military ruler General Zia, and he took a leaf out of the Tony Blair speech-book on Princess Diana. ‘I’d like to be seen as the people’s general,’ he told me.

But on the eve of the millennium the international community had little stomach for coups. Another one in Pakistan seemed a retrograde step in a country that had spent half its existence under military rule. Pakistan was expelled from the Commonwealth. Even Pakistan’s traditional friend Saudi Arabia was showing a cold shoulder; the Saudi royal family was close to the Sharifs, and would go on to provide them with homes in exile.

It wasn’t just the way that Musharraf had seized power that caused international concern. Pakistan and India had fought three wars over the disputed province of Kashmir, and five months before his coup, the then army chief Musharraf had brought the two nations to the verge of a fourth, this time nuclear. As Musharraf liked to remind people, his background was as a commando, and in May 1999 he ordered Pakistani troops into Indian Kashmir disguised as jihadis. The plan was to seize a 15,000-foot strategic height called Kargil. The ill-conceived operation prompted a fierce reaction from India, which responded with aerial bombardments. Western intelligence picked up that the Pakistani army was preparing nuclear missiles.

The Kargil operation totally undermined Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s efforts to make peace with India after Pakistan’s nuclear tests the previous year, and he always insisted it was launched without his knowledge. He pointed out that he had just signed the Lahore Declaration with his Indian counterpart Atal Bihari Vajpayee, a bilateral treaty to normalise relations between the two countries, and that it would make no sense to then wreck it by sending troops across the agreed Line of Control which divides Kashmir. Musharraf pooh-poohed the idea that Sharif did not know, saying, ‘Nothing could be farther from the truth.’ He claimed the Prime Minister was briefed three times.