По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

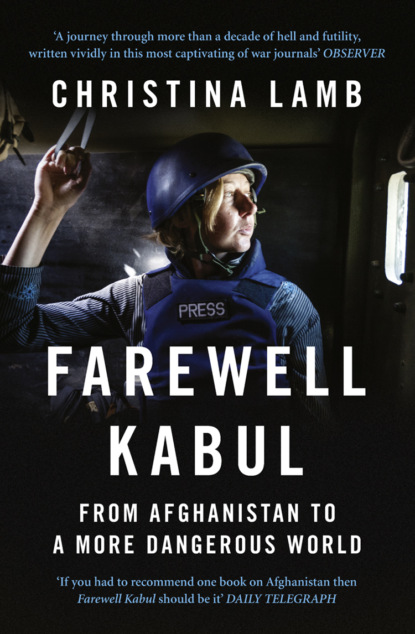

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I kept thinking of what Karzai had told me about Pakistan. Before we were locked in I managed to go to the frontier town of Chaman, where I met a chief of the Achakzai tribe, whose people lived on both sides of the border and controlled the smuggling routes in and out. He told me that trucks coming from the National Logistics Company of Pakistan’s army, supposedly transporting flour, were actually full of weapons for the Taliban.

Nine days into the bombing, on 16 October, a second CIA team, Team Alpha, arrived in Afghanistan, joining General Abdul Rashid Dostum in the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif. The choice caused consternation among the Northern Alliance leadership. The whisky-loving Uzbek and his feared Jowzjan militia were notorious for atrocities, such as driving over prisoners with tanks, and had fought alongside the Soviets during the jihad, fighting pitched battles against Ahmat Shah Massoud’s forces. Dostum switched over to the mujaheddin in 1992 when the fall of the Soviet-backed President Mohammad Najibullah was imminent, and had only recently linked up with the Northern Alliance. In their view he was not to be trusted. They thought the CIA team should have been placed with their long-time commander Mohammad Ustad Atta, Dostum’s rival for control of the city.

The first US military to set foot in Afghanistan was special forces team ODA 555, codenamed ‘Triple Nickel’, which was flown in from Uzbekistan and landed on the Shomali plains north of Kabul on 19 October to join Marshal Fahim and his CIA advisers. The following day a second special forces team, ODA 595, joined General Dostum in the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif. A third group was dropped south of Kandahar. Using SOFLAMs, they laser-guided bombs from US fighter jets onto Taliban targets with such precision that Dostum bragged on the radio to Taliban that he had a ‘death ray’. They also attempted to organise the Afghan fighters, and were joined by SAS and some Australian special forces.

Back in Quetta, the nights had started to chill. We had all grown tired of the nightly lamb barbecue and fresh apple juice in the orchard. American newspapers were already talking of quagmires. It felt as if we might be there for a long time.

One day, shortly after the bombing had started, I knocked at Karzai’s door to be told by his assistant, Malik, that he had gone away.

‘Where has he gone?’ I asked.

‘Karachi,’ he replied.

Malik was not a good liar. ‘He’s gone to Afghanistan, hasn’t he?’ I said.

Karzai had told me he’d been planning to go to southern Afghanistan to try to raise support. I’d begged him to take me along. ‘Taking you inside is as easy as cracking this nut,’ he had said, holding up an almond. ‘The problem is what to do then.’

He’d always felt insecure about the fact that he hadn’t actually fought in the jihad. The only time he had gone inside Afghanistan during the war against the Russians was our trip to Kandahar in 1988. If he was going to play an important role in whatever government replaced the Taliban, he needed to prove his bravery. Also, Pakistan had cancelled his visa, so if he stayed in Quetta he could be arrested.

His intention was to go and rally the southern tribes against the Taliban. He seemed to think this would be quite easy. I couldn’t help remembering our own trip to Kandahar, and the way we kept almost being bombed by the Russians as he naïvely broadcast his presence everywhere by radio. Now he was heading into the Taliban’s own backyard.

Ahmed Wali said he’d tried to dissuade him, but to no avail. One day Karzai told his wife he was going to visit some relatives near the border, and to pack him a toothbrush. ‘If I don’t come back after two days forget about me,’ he had said.

He’d set off on a second-hand motorbike, accompanied by a few trusted elders. He had asked for help from the CIA, meeting with his case officer ‘Casper’ in Islamabad. They thought his mission was crazy, so provided him only with a satellite phone and an emergency phone number. He was so poorly equipped that he had to send someone back out to Ahmed Wali in Quetta on a motorbike with the phone batteries for charging.

Over in the east, another old friend from the jihad days had gone into Afghanistan with the same idea. Abdul Haq had been the main mujaheddin commander in the Kabul area during the Russian occupation, and had lost his right foot to a landmine. Like Karzai he was a long-time critic of ISI. He had kept fighting, but eventually left Peshawar for Dubai after his wife and son had been killed there in 1999 – he believed by ISI. After 9/11 he returned to Peshawar and began renewing his old mujaheddin networks. While Karzai headed west, Abdul Haq gathered supporters to head into his home area of eastern Afghanistan around Jalalabad, where his family were very influential, and planned to start a Pashtun uprising against the Taliban.

A charismatic man with twinkling eyes, Abdul Haq always liked to talk. Back in the eighties I had spent many afternoons with him in his house in Peshawar, eating pink ice cream and listening to his stories of the war and why it was going wrong. Predictably, he had told journalists of his plans before setting off over the border on 21 October with his nephew Izzatullah and seventeen men, mostly veterans of the jihad. They had travelled in pick-ups, crossing the border the old way near Parachinar, stopping for the night under the stars, sleeping under Orion and the Milky Way.

It was hard for Haq to walk far over the rugged mountains because of his artificial foot, so the next morning they mounted horses in Jaji, near where bin Laden used to have a camp. They rode through the Alikhel gorge, which had been a favourite spot for ambushing Soviet convoys. But just as their own forces had cut off that road in the past, they soon found themselves cut off by the Taliban, and in the midst of a firefight.

As the bullets were flying, Izzatullah ducked behind a rock and managed to make a call to the US on the satellite phone. He telephoned Bud McFarlane, a retired CIA agent who had been a long-time backer of his uncle. McFarlane contacted the Agency headquarters at Langley, Virginia. But they could do nothing, and the men were captured and taken to Jalalabad.

On 26 October we got the news that Haq had been executed. He was forty-three. I was horrified. He seemed to me to have been one of the genuinely good people, and someone who might have been critical for Afghanistan’s future. His friends believed he had been betrayed by ISI.

I was worried about Karzai.

Frustrated by not being able to report freely in Quetta, I flew to Karachi to meet Mufti Nizamuddin Shamzai, a cleric close to Mullah Omar and the Taliban who headed the Banuri complex, the city’s largest madrassa. Some said it was he who had first introduced Mullah Omar and bin Laden. He laughed at the idea that Pakistan had stopped supporting the Taliban. He had personally declared a fatwa against the US.

The evening I returned to Quetta I went to Ahmed Wali’s house. We spoke to Karzai on the satellite phone, and he told me some of the things he had seen crossing the border. I got back to the Serena just before the 9 p.m. curfew, planning to write my story for my paper the next day.

I am lucky to sleep well even in war zones, and was deeply asleep when around 2 a.m. I was woken by pounding on my door. Through the spyhole I could see the hotel’s duty manager with a group of five men. Wearing grey shalwar kamiz and aviator glasses even at night, they were instantly identifiable as ISI.

‘There are some guests for you,’ said the duty manager.

‘It’s the middle of the night!’ I protested. ‘Tell them to come back in the morning.’

I started walking back to my bed, but the duty manager had the room key, and one of the men in grey snapped the door chain. I was shocked rather than scared. I was in pyjamas, and to have strange men barging into my room in an Islamic country where I had always thought there was respect for women was unbelievable. They snatched my mobile phone, which was charging on the side cabinet, and told me I was going with them.

They let me dress after I protested, then marched me downstairs to reception, where I was made to pay my bill before leaving. I was glad when another group of men appeared holding Justin Sutcliffe, the photographer I was working with. They tried to put us in separate vehicles, but we made so much fuss that they finally bundled us into the same jeep, and we were driven off into the night.

The streets were deserted because of the curfew, and for the first time I felt scared. They could do anything they liked with us, and nobody would know. I was relieved when we turned into a driveway rather than out into the vast Baluch desert. At the end was an abandoned bungalow. Inside, the only furniture was a bed. We were told to sleep while our nine guards sat around and watched. We later discovered this was the old rest-house of Pakistan Railways from colonial times. Fortunately Justin always travelled with spare supplies, and he whispered to me that he had managed to secrete a phone in a pocket. During the night he went to the toilet, from which he called our newspaper while I distracted the guards by pretending to be hysterical. None of our editors answered, as it was the middle of the night back in the UK, but eventually Justin managed to get hold of our Washington correspondent, David Wastell.

The next night our guards drove us to the airport, radioing colleagues with the code ‘The eagle has landed.’ We were put on a flight to Islamabad and handed over to the FIA, another Pakistani intelligence agency, where no one seemed to know who had ordered our arrest or why. The FIA Director was at a loss what to do, as his cells were being rebuilt, so he kindly fed us some of his own curry dinner and put us under guard in the VIP section of the departure lounge. The next day a diplomat came from the British High Commission, who unhelpfully told us the best thing in terms of our security would be if we left Pakistan. We were unceremoniously deported.

The typed expulsion notices were dated 3 November 2001, and signed by Shah Rukh Nusrat, Deputy Secretary to the government of Pakistan. Mine stated: ‘Whereas Miss Christina Lamb, British national acting in manner prejudicial to the external affairs and security of Pakistan it is necessary that she may be externed from Pakistan. Now because in exercise of the powers conferred by section 3 subsection 2 clause C of the Foreigners Act the federal government is pleased to direct that the Miss shall not remain in Pakistan and should leave the country immediately.’

The Pakistani newspapers printed a ludicrous story, fed from ISI, that we had tried to buy a plane ticket in the name of Osama bin Laden. Years later I would still get asked why we had done this.

My relationship with Pakistan had been conflicted since my previous deportation. As we were led onto the PIA plane (having been asked to pay for the ticket, which we refused to do), I vowed I would never go back.

Shortly after take-off, one of the stewardesses came and said the pilot was inviting us into the cockpit. We were astonished. This was less than two months after 9/11, and the world’s airlines had all issued instructions to keep cockpits locked. I pointed out we had been deported as threats to national security, but she just smiled and led us to the front. Inside the cockpit was Captain Johnny Afridi, the plane’s pilot, a Pashtun with John Lennon glasses and a long, skinny ponytail. ‘Don’t worry about those goons,’ he laughed. ‘I’ve been arrested too.’ By the end of a very entertaining flight, sitting in the cockpit for a spectacular sunset landing at Heathrow, my resolve never to return to Pakistan was forgotten.

Back in London we were called into the Foreign Office to meet the head of the consular service. I was furious that they had done nothing to fight our case – we were from one of Britain’s leading newspapers, the Sunday Telegraph, and had been trying to report on a war in which Britain was involved.

‘You must understand Pakistan are our allies,’ we were told. ‘We need their support during the bombing campaign. It’s a very sensitive time.’ We later learned that four Pakistani bases in Sindh and Baluchistan were being used to fly some of the bombing raids.

It was a bright sunny day, but as we walked out into St James’s I blinked back angry tears. It seemed my war was over before it had even started.

Meanwhile, in Afghanistan everything was suddenly happening very quickly. Since the start of November the US had agreed to all the urging from the Northern Alliance commanders, and begun pounding Taliban front lines with giant daisy-cutter bombs dropped from AC-130s. Gary Schroen and his CIA team were monitoring Taliban radio traffic, and could literally hear the fear. ‘Our guys were listening to the radios and the panic, the screaming, the shouting as bunkers down the line were going up from 2,000-pound bombs,’ he said. ‘I mean, they were just simply devastated, and they broke.’

There was no more talk of quagmire. Mazar-i-Sharif fell to Dostum’s men on 10 November. ‘This whole thing might unravel like a cheap suit,’ President Bush told President Putin.

The Taliban quickly realised it was no contest, and by 13 November had fled Kabul, leaving the Northern Alliance to move in. By the beginning of December they were gone from all the major cities apart from their heartland of Kandahar in the south, which they finally abandoned on 7 December. ‘I think everybody was surprised (with the possible exception of [US Defense Secretary] Don Rumsfeld, who would have felt vindicated) at the result of military intervention, which was nasty, brutish and short,’ said Lieutenant General Sir Robert Fry, commandant of the Royal Marines at the time, who went on to be Director of Military Operations at the Ministry of Defence. ‘It was remarkably successful in that there were negligible Western casualties. You had overwhelming Western firepower, loads of CIA playing the Great Game with buckets of money, and a compliant infantry in the shape of the Northern Alliance. All of a sudden they thought they’d found the philosopher’s stone of intervention.’

New technology, like laser-guided bombs, had avoided a major deployment of troops. To overthrow the Taliban the US had put on the ground fewer than five hundred men – 316 special forces and 110 CIA officers. Only four American soldiers and one CIA agent had been killed, and three of those soldiers were killed by their own bomb – in ‘friendly fire’. The whole operation had cost only $3.8 billion. The CIA estimated it had spent $70 million, mostly in bribes to Afghan commanders. President Bush called it one of the biggest ‘bargains’ of all time.

So easy did it seem that on 21 November, while US forces were still fighting the Taliban, Bush had secretly already directed Rumsfeld to begin planning for a war with Iraq. ‘Let’s get started on this and get Tommy Franks looking at what it would take to protect America by removing Saddam Hussein,’ he said.

General Franks, the commander of US Central Command, was sitting in his office at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida, working on plans for Afghanistan when he got the phone call from Rumsfeld. ‘Son of a bitch. No rest for the weary,’ is how he recalled his reaction in his memoir. Bob Woodward’s book Plan of Attack has a rather different account. ‘Goddamn, what the fuck are they talking about?’ Franks is reported as saying. ‘They were in the midst of one war, Afghanistan, and now they wanted detailed planning for another?’

Back in London, Justin and I got help from an unexpected source when Iran obliged us with visas to get into Afghanistan from the west. We flew to Tehran, then to the pilgrim town of Mashad near the border, and drove into Herat the day after the Taliban left. We were helped by Ismael Khan, a warlord who looked the part, with his flowing beard and trucks of neatly clad but fearsome gunmen who accompanied him everywhere. I’d first met Ismael when I went to Herat during Russian times, and his resistance was legendary. He had been imprisoned during the Taliban after being betrayed by General Dostum’s men, though he’d managed to escape. Although part of the Northern Alliance he had his own status as ‘the Emir of the West’, and as soon as the Taliban left he took power in his home city.

From Herat we managed to catch the first Ariana flight to Kabul, a nerve-racking experience, as I’d never before been on a plane that had to be jump-started. As we flew awfully close to mountains, the pilot told us the only instrument working was his ‘vision’.

But we made it, and found ourselves in the Mustafa. It had been a complicated journey that in a way felt the culmination of years, not just months. We had hardly any electricity and little food, but we were happy. Wais even got hold of a TV so we could watch BBC World on the occasions when there was electricity.

The challenges ahead were brutally clear. There was destruction everywhere – parts of the city such as Jadi Maiwand, the old carpet bazaar, and the road to Dar ul Aman palace, resembled pictures of Dresden after the bombing of the Second World War. The once sparkling-blue Kabul River was a brown trickle clogged with evil-smelling garbage. I went to visit the Children’s Hospital, where the doctors told me the power often went off in the middle of surgery, so children just died. My own son had been born more than eleven weeks premature two years earlier, and I asked a doctor what would happen to him if he were born in the hospital. The doctor looked at me as if I was mad. ‘He would die of course,’ he said. Afghanistan was the worst place in the world to be a mother or a child.

After I wrote of this in the Sunday Telegraph, generous readers raised money for a generator which the British military agreed to fly out. In what should have been a warning for the future, once it reached the hospital the generator disappeared.

Everyone was promising not to abandon Afghanistan again. It had been a model war, and the plan was for a model construction of democracy. There would be no more ‘ungoverned space’ which terrorists could move into and use as launching pads for attacks. ‘You abandoned us last time and got bitten by a scorpion,’ warned Hamid Gilani, whose father Pir Gilani was one of the seven jihadi leaders who had raised arms against the Russians. ‘If you abandon us this time you’ll get bitten by a cobra.’

We all assumed foreign aid would pour in to turn Afghanistan around – a donors’ conference was scheduled for Tokyo, and there was talk of billions being pledged. Already there were lots of aid agencies moving in. Kabul was the new sexy place to be, and every day more people arrived at the Mustafa, prompting effusive reunions. ‘Hey, I last saw you in East Timor/Kosovo/Bosnia/Sierra Leone …!’ became a common refrain.

There were French lawyers arriving to draw up a constitution. Feminists setting up gender-awareness classes, a women’s bakery and a beauty school for which American beauty editors sent make-up. There would even be estate agents, as so many aid agencies coming in pushed rents sky high. Elections were planned for the following spring. But when I talked to my Afghan friends, nobody mentioned democracy or women’s rights. They wanted security and food and speedy justice.

The West had its swift military success, dismantling the Taliban regime in two months. I don’t think anybody spoke to ordinary Afghans about what they wanted.