По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

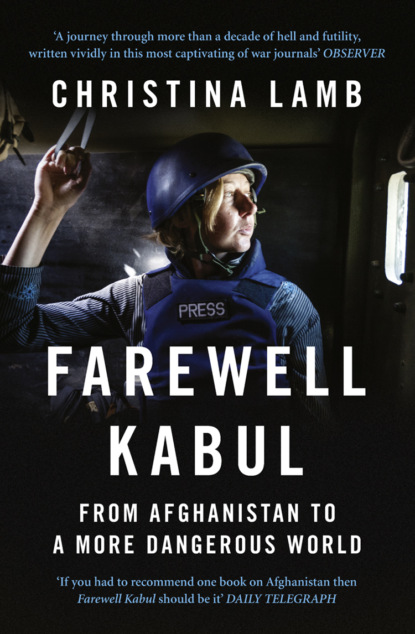

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There would be no victory parades, for there had been no victory. Lofty aims of transforming the country were forgotten. Now it was about damage control. ‘Helmand is not the Western Front; it doesn’t end in a hall of mirrors in Versailles like 1918,’ said Brigadier Rob Thomson. ‘I don’t think wars today end in defeat or victory; you set the conditions to allow other elements to come in.’

The question on everyone’s lips was how long would it be till the Taliban raised their black flags instead? Already they were back in many districts, showing their presence, if not yet hoisting flags.

Brigadier Thomson would not be drawn on the future. ‘There’s clearly going to be a contest,’ he said, ‘and it would be foolish of me to make a prediction into the long term about how this will run.’ The Taliban, meanwhile, had already declared victory. ‘The flight of the British invaders is another proud event in the history of Afghanistan,’ said their spokesman.

Locals watched and shrugged at the latest foreigners to come and leave their country. They had been surprised when the Angrez, as they called the British, came back, for the British Army had suffered one of the worst defeats in its history at nearby Maiwand in 1880. No one had ever really explained why they had returned, if not to avenge that. Nor had they understood what the point of killing Taliban was, when more just came over the border from Pakistan, a country which had received more than $20 billion in Western aid since 9/11, and turned out to have been hosting bin Laden.

So the farmers just got on and harvested their poppy, for it would be a record crop of more than 200,000 hectares, almost half of that in Helmand, by far the world’s biggest producer. Most villages still had no jobs, no electricity, no services.

Ministry of Defence bureaucrats could spend money commissioning slick ‘legacy videos’, but the truth was that Britain’s fourth war in Afghanistan had ended in ignominious departure. It had been the country’s longest war since the Hundred Years War, longer than the Napoleonic Wars, and the most deadly since the Korean.

British officers might be lobbing accusations at each other, but Helmand was a reflection of the whole war in Afghanistan. In the thirteen years since invading Afghanistan in response to 9/11, NATO forces had lost 3,484 troops and spent perhaps $1 trillion. For the Americans, who lost the most soldiers and footed most of the bill, it was their longest ever war. What had once been the right thing to do – what President Barack Obama called ‘the good war’ – had become something everyone wanted to wash their hands of.

How on earth had the might of NATO, forty-eight countries with satellites in the skies, 140,000 troops dropping missiles the price of a Porsche, not managed to defeat a group of ragtag religious students and farmers led by a one-eyed mullah his own colleagues described as ‘dumb in the mouth’? And why had they even tried?

Overall, more than $3 trillion had been spent in Iraq and Afghanistan in response to a terrorist attack that cost only between $400,000 and $500,000 to mount.1 (#litres_trial_promo) The aim, as stated by Gordon Brown while he was Prime Minister, was that ‘We fought them over there to not fight them here.’ Yet it was hard to see how these wars had left the West safer. On the contrary, we had ended up with the Pakistani Taliban, who were far more dangerous than the original Afghan Taliban, and regional offshoots of al Qaeda like al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in Yemen, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in North Africa, al Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria. Mullah Omar was still at large, as was Ayman al Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s deputy, who had succeeded him as leader. Some of the original al Qaeda from Afghanistan/Pakistan that was supposed to have been incapacitated had turned up under the name Khorasan in Syria. Lastly, there was ISIS, the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, far larger and more terrifying than al Qaeda, which by the end of 2014 controlled territory the size of Britain in Iraq and Syria, as well as making inroads in Libya. ISIS had declared a Caliphate, and was vowing to extend its reign of terror and beheadings as far as Spain, prompting the US and Britain to send advisers back to Iraq, and sucking them back into their fourth war since 9/11. So many Europeans had been attracted as jihadists into its ranks that intelligence chiefs were warning an attack on British soil was ‘almost inevitable’.

From Libya to Ukraine, around the world conflicts were springing up everywhere, like the Whack-a-Mole arcade game in which no matter how many moles are smashed with a hammer, more simply pop up elsewhere. There were more countries undergoing wars or active insurgencies than at any time since the Second World War, yet never had the major powers been wearier of intervention. What had started with hopes of a new world for Afghan women had ended with medieval black-hooded executioners, religious wars across the Middle East, and Jordan’s King Abdullah warning that World War III was at hand.2 (#litres_trial_promo)

As for Afghanistan, schools, clinics and roads had been built across the country, yet it remained one of the poorest places on earth. By the end of 2014 the US would have spent more on Afghanistan than it had on the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after the Second World War. Yet poverty remained stubbornly high, with more than a third of Afghans still surviving on less than 80p a day, according to the United Nations Development Programme, and half its children having never set foot in a classroom.3 (#litres_trial_promo) In a land where 70 per cent of the population was under thirty, the majority had only ever known war. War against the Russians, war against each other, war between the West and al Qaeda and the Taliban. In this last, 15,000 Afghan troops had died, as well as more than 22,000 civilians, and the numbers were going up each year.

The West’s relations with the country it had been trying to help, and the ruler it had installed, had deteriorated to such an extent that in President Hamid Karzai’s farewell speech to his cabinet in late September 2014, there were no thanks for Britain or America. Instead he blamed America – as well as Pakistan – for not wanting peace. ‘We are losing our lives in a war of foreigners,’ he raged.

No one who goes to war comes back unchanged. I spent two wars in Afghanistan – the first as a recent graduate (covering the final showdown of the Cold War), the second as a new mum in the aftermath of 9/11 (covering a war involving my own country). I left a middle-aged woman who had more than used up her nine lives, with a teenage son going into a world far more ominous than that in which I grew up.

This book sets out to tell the story, by someone who lived through it, of how we turned success into defeat. It is the story of well-intentioned men and women going into a place they did not understand at all – even though, in the case of the British, there was plenty of past history. The 1915 ‘Field Notes on Afghanistan’ given to those heading out to the Third Anglo–Afghan War are full of salutary warnings, starting right off with ‘Afghans are treacherous and generally inclined towards double dealing.’ Major General Dickie Davis, sent to Afghanistan in 2002, recalls how when he was briefed on the mission at military headquarters (PJHQ) before departing, he asked, ‘How many hundreds of years have we got?’4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Anyone visiting the NATO military headquarters in Kabul might be struck by the number of saplings planted on the small green over the years – one for each commander. There had been seventeen in the course of the war. In Helmand alone Britain had had seventeen commanders, each there for just six months. They might wonder too how a war could be fought effectively when there was no real border with the neighbouring country of Pakistan, which the enemy made its safe haven.

Yet more than a military failure, this was a political failure. Just as a lack of imagination had failed to predict the possibility of using passenger aeroplanes as weapons, a lack of imagination caused us to assume people wanted the same as us, and that because our enemy were uneducated they were ignorant savages we could easily outsmart. It was a strategy that ignored tribal realities and other people’s national interests, including those of our key partner. Along the way, the West lost the moral high ground by giving positions of power to those the Afghan people most blamed for the war, and by the detention and torture of prisoners, some of whom had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Over those thirteen years I watched with growing incredulity as we fought a war with our hands tied, committed too little too late, became distracted by a new war of our own making based on wrong information, and turned a blind eye as our enemy was being helped by our own ally. Yet only when Osama bin Laden was found living in a house in a Pakistani city, not far from the capital, did it seem to dawn on people that we may have been fighting the wrong war.

Throughout this period I lived in Pakistan, Afghanistan, London and Washington, as well as covering the other war and its aftermath in Iraq, and visiting Saudi Arabia, which was the birthplace of fifteen of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers. I spoke to almost all key decision-makers, including heads of state and generals, as well as embedding with American soldiers and British squaddies actually fighting the wars. Most of all I talked to people on the ground. I travelled the length and breadth of Pakistan, from the tribal areas to the mountain valleys of Swat, from the cities of Quetta, Lahore and Karachi to the jihadist recruiting grounds in madrassas and in remote villages of the Punjab. In Afghanistan my travels took me far beyond Helmand – from the caves of Tora Bora in the south to the mountainous badlands of Kunar in the east; from Herat, city of poets and minarets in the west, to the very poorest province of Samangan in the north, full of abandoned ghost villages. I also travelled to Guantánamo, met Taliban in Quetta and from the Quetta shura, visited jihadi camps in Pakistan, and saw bin Laden’s house just after he was killed. Saddest of all, I met women whom we had made into role models and who had then been shot, raped, or forced to flee the country.

On the way I had several narrow escapes – from being ambushed by Taliban with the first British combat troops in Helmand to travelling on Benazir Bhutto’s bus when it was blown up in Pakistan’s biggest ever suicide bomb. I lost many friends in those years, a number of whom appear in the following pages.

I could not have lived through all this and just walked away. I have written this book because I thought it was a story that needed telling. How it ends is yet to be told.

PART I

GETTING IN (#ue110efdd-99ae-5c21-ae82-f889fc3c445e)

British general to Afghan tribal chief in 1842 during the First Anglo–Afghan War: ‘Why are you laughing?’

Tribal chief: ‘Because I can see how easy it was for you to get your troops in here. What I don’t understand is how you plan to get them out.’

1

Rule Number One (#ue110efdd-99ae-5c21-ae82-f889fc3c445e)

Kabul, Christmas Eve 2001

I sat on the roof of the Mustafa Hotel on the seat of an old Soviet MiG fighter jet and looked out over Kabul feeling happy. Happy endings are few and far between in my foreign correspondent world, where we fly in to report war, misery and disaster in time for our deadlines, then out again back to our comfortable lives, disturbed only by an occasional nightmare or sad memory that floods in unexpectedly to darken a moment.

The hills all around were dotted with tiny wattle houses in squares of beige and sky-blue, melding into each other like a Braque painting. There was ‘Swimming Pool Hill’, named after the Olympic-sized concrete pool the Russians had built on its top, long empty and last used by Taliban to push blindfolded homosexuals to their deaths off the diving tower; ‘TV Mountain’, with a broken antenna and littered with rocket casings from years as a major battleground for rival mujaheddin groups; and ‘Cannon Hill’, where until all the fighting started an old man would fire off a cannon every day at noon, a tradition begun in the nineteenth century by the ‘Iron King’ Abdur Rahman to give his unruly countrymen a sense of time.

Along the tops I could see remains of the old city walls picked out in relief, starting and ending at the Bala Hissar fortress, an ancient polygon of walls which crowned Lion’s Gate Mountain and managed to be both crumbling and imposing. The name means ‘high fort’, and from this perch for centuries ruled Afghan kings (some of whom ended up in its dungeons, the Black Pit) and, long ago, some of the world’s mightiest conquerors. Among them were Timur the Lame, the Tartar despot who levelled cities from Moscow to Baghdad and built towers from the skulls of their people; and Babur, the first Moghul Emperor, who adored Kabul for its gardens, where he counted thirty-two different kinds of tulips. Babur loved this city, describing it as ‘the most pleasing climate in the world … within a day’s ride it is possible to reach a place where the snow never falls. But within two hours one can go where the snow never melts.’

I loved it too, even though it was a long time since Kabul had been a city of gardens. Rather it was a city of ghosts, many of whose bodies were buried in the hills. Some of them were from my own country. Britain had fought two wars with Afghanistan, losing two and perhaps drawing the third. Yet initially the country seemed so benign that when British forces first stormed Kabul Gate in 1838, to oust king Dost Mohammed and install their own king, Shah Shuja, they took with them their wives, hundreds of camels laden with provisions such as smoked salmon, cigars and port, and even packs of hounds for hunting foxes in the Hindu Kush. Wives wrote of swapping tips on growing sweet peas and geraniums with local Afghans1 (#litres_trial_promo) and of outings to boat on the lake or ice-skate in winter. By January 1842 the British would have fled. The king they had installed on a gilded throne under richly painted ceilings in the Great Hall of the Bala Hissar and described as “a man of great personal beauty”2 (#litres_trial_promo) ended up slaughtered at its gates. The defeat of what was then the most powerful nation on earth – and slaughter of thousands of its forces – by marauding tribesmen was the greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the West in the East.

Yet they went back. In the second war, the British Envoy Sir Louis Cavagnari was hacked to death in his residence inside the fort in September 1879 by tribal brigands angry at not being paid promised stipends, and at British interference in their land. In revenge the British general Frederick Roberts led a column on Kabul called the ‘Army of Retribution’, and had forty-nine tribal leaders hanged from gallows inside the Bala Hissar. He ordered the fort’s destruction as ‘a lasting memorial of our ability to avenge our countrymen’, though in the end it was left. Such was the feared reputation of the land of the Bala Hissar that in 1963 Britain’s Prime Minister Harold Macmillan would declare, ‘Rule number one in politics – Never Invade Afghanistan.’

I had first travelled in these valleys and mountains in the late 1980s when the Russians were being driven out, so was only too familiar with all those stories of Afghanistan as the ‘Graveyard of Empires’. Indeed, Kabul still had a British cemetery, with graves going back to those killed in the First Anglo–Afghan War, if any reminder were needed.

But if we knew those things then, we were not thinking about them. If I shivered, it was because of the cold. The first snow was falling softly, and loud Bollywood music blared discordantly from the street below. On the roof were other journalists from Japan, Italy and Australia, shuffling around their satellite dishes to try to find the right angle to locate satellites in the sky so they could magically transmit their copy to their foreign desks. ‘Oh for fuck’s sake, bring back the Taliban!’ joked one, struggling to be heard over the jarring music. I laughed, catching a snowflake on my tongue and thinking there was nowhere I would rather be.

Everything had happened so quickly it was hard to take in. On 11 September 2001 I had just moved to Portugal with my husband and two-year-old son when my sister-in-law called telling me to switch on the news. We hadn’t yet got a television so we headed to a local piri-piri chicken café which had a large screen to show football matches to English tourists. Watching the planes fly through the brilliant blue sky of a Manhattan morning and smash into the iconic towers of the World Trade Center was impossible to comprehend, no matter how many times we watched.

Then we heard two other passenger planes had crashed – one into the Pentagon and one into a field in Pennsylvania. I held my son tight, for it was clear that nothing would be the same again.

It wasn’t long before the TV commentators were joining the dots to Saudi billionaire’s son Osama bin Laden, who had vowed war on the United States. Soon they were focusing their pointers on maps of Afghanistan where the al Qaeda leader had fought in the 1980s and been living under the protection of the Taliban since 1996.

Who were the Taliban, and their mysterious one-eyed leader Mullah Omar? It was a regime about which the West knew so little that when 9/11 happened, Jonathan Powell, Chief of Staff to British Prime Minister Tony Blair, sent out his staff to buy all the books they could on the Taliban.3 (#litres_trial_promo) They had only been able to find one – Ahmed Rashid’s Taliban, which had struggled to find a publisher. Now it was a best-seller and everyone had heard of the zealots who wanted to lock away Afghanistan’s women and take the country back to the seventh century.

Editors who had not been in the least interested in goings on in Afghanistan suddenly could not get enough stories of the horrors of life under the Taliban. For weeks we had been writing about the women lashed for wearing nail varnish or white shoes; the men beaten with logs for not having beards as long as two fists; the sports stadiums used for amputations and executions; and the banning of everything from chess to music.

Now, just two months later, they had been driven out. In Kabul, everyone seemed to be out on the streets, hearing each other’s stories, like people inspecting the damage after a massive storm. The reports we were sending were upbeat tales of life beginning again: girls’ schools reopening, women casting off the blue burqas they had been made to wear. On every street there were people hammering Coke and 7 Up cans into satellite dishes. In a teahouse I came across the first meeting of a long-banned chess club; in the bookshop around the corner from the hotel was Shah Mohammad Rais, who had hidden his books to prevent the Taliban burning them. In the National Gallery I found a man with a sponge and bucket washing off the trees and lakes he had painted over faces on artworks so the Taliban would not destroy them.

Most magical of all were the kites flying from the rooftops. On the road up to the Intercontinental Hotel (that wasn’t really an Intercontinental) a parade of tiny kite shops had reopened. Inside each sat a man wrapping bamboo frames with tissue paper then pasting on shapes in bright pinks, yellows and blues like a Matisse collage and finally rolling the string onto giant reels. Each man claimed to be the most famous kite-maker in Kabul. We didn’t know then that the string would be coated with ground glass, and the objective was to cut down kites of other boys (even then, we never saw girls flying kites).

The story I had written that day was of an encounter with British Royal Marines on Chicken Street, a favourite destination back in the days of the hippie trail, with all its little shops selling carpets, shawls, and lapis and garnet stones set into silver rings that would soon blacken. The soldiers were the first arrivals of the International Stabilisation Assistance Force (ISAF), which was quickly nicknamed the International Shopping Assistance Force.

The first foreign troops to enter Kabul since the Russian occupation twelve years earlier, the British were warmly welcomed by locals. After years of civil war, many Afghans saw foreigners as the only way to end the fighting so they could get on with life. The fact that of all people they were British, back for more, seemed to endear them further to the locals. The British soldiers sat on top of their armoured personnel carriers handing out sweets to Afghan children and cigarettes to the men, and all round it was smiles.

‘Hello my sister, what gives?’ Wais Faizi, the hotel’s manager, was a thirty-one-year-old Afghan with a fast-talking New Jersey patois like the car salesman he had once been. ‘The Fonz of Kabul’, we called him. His family had owned the Mustafa for years, until it was seized by communists around the time of the Soviet invasion in 1979, and they had fled to America when he was just a child. They had recently returned to Afghanistan, and had been in the process of converting the Mustafa into a gemstone and money exchange when 9/11 happened and Kabul unexpectedly became the focus of world attention. So they quickly turned it back into a hotel, just in time for the flood of journalists, though with not enough time to actually make the rooms comfortable.

‘Chai sabz?’ Wais handed me a mug of green tea.

‘Tashakor.’ I thanked him. It had about as much taste as old dishwater, but it was warm, tendrils of steam rising in the frigid air, and I cupped my hands gratefully around the sides.

‘Still working on the espresso machine,’ he apologised. He found his home country harder to get used to than we nomad journalists did, and often talked wistfully of Dunkin’ Donuts and Domino’s Pizza. A coffee machine would actually be useless, given how rarely we had electricity; and when it came it was in gadget-destroying bursts. But if anyone could get one, it would be Wais. He’d already turned one of the rooms into a makeshift gym, complete with some dumbbells bought from a warlord, and decorated with posters of his hero Al Pacino.

Wais had even managed to get hold of the only convertible in Kabul, a 1968 Chevy Camaro which had belonged to one of the Afghan princes before the King was deposed, and had taken me for a spin. We’d had a glorious afternoon driving around the ruins of Kabul, children waving in astonishment, carpet-beaters jumping out of the way and men wobbling on their bikes at the sight of a foreign woman in an open-top car and headscarf fancying herself as Grace Kelly.

Next he had promised us a bar, and he was organising a Christmas dinner, for, unbelievably, he had found someone in the Panjshir valley who raised turkeys. It would make a change from the past-their-date tuna ready-meals, peanut butter and white-furred bars of Cadbury’s chocolate we had been living on from Chelsey (sic) Supermarket, where Osama bin Laden’s Arabs used to shop.

I caught another snowflake on the tip of my tongue. ‘Christina jan, don’t eat the snow – it’s full of shit!’ admonished Wais. He meant it literally. Everyone in Kabul seemed to have a permanent cough, and Americans I met loved to tell me the air was full of faecal matter – waste went straight into the streets, and the smoke rising from the houses on the hills was from pats of animal dung that people burned as fuel.