По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

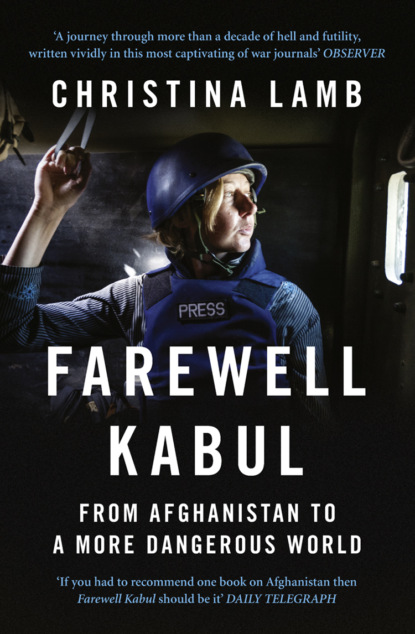

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No thanks to your horrid pigeons!’ I replied. Wais had recently discovered Kabul’s old Bird Market, which sold anything from tiny orange-beaked finches to strutting roosters, all meant for fighting. There, he had acquired a flock of burbling pigeons which he kept in a glass coop in the open courtyard in the centre of the hotel. Pigeon-flying was popular in Kabul, where houses had flat roofs and people trained them to take off as if by remote control then loop the loop by waving a stick called a tor, with a piece of black cloth on the end. As always in Afghanistan, it wasn’t a benign pastime: the real aim was to try to get someone’s rival flock to land on your rooftop. You could usually tell pigeon-trainers by their beak-scarred hands.

Wais claimed the pigeons reminded him of the blue mosque in the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif, a building surrounded by so many white doves that when they take to the air it feels like being inside a just-shaken snowglobe. But to me they were completely different. Pigeons, I reminded him, had left the young Emperor Babur fatherless at thirteen, when his father fell from his dovecote. ‘The pigeons and my father took flight to the next world,’ he’d written in his journal.

‘Why can’t you fly kites instead of pigeons?’ I asked.

‘You of all people should like the pigeons,’ Wais laughed. ‘When they fly they always follow the lead of a female.’

The music stopped, its owner perhaps paid off by some exasperated journalist, and I could hear peals of children’s laughter. Down on the pavement some local street kids were jumping and diving, trying to catch the snow, which was starting to fall more thickly, sending cloth-wrapped figures scurrying to their homes. Soon I would be driven inside too, to one of the freezing glass-partitioned cells with metal bars on the outside that passed for rooms at the Mustafa. But for a moment I wanted to enjoy the rare sight of children playing in this country which had seen more than twenty years of war.

The mood in Washington and Whitehall was also celebratory. Just sixty days after the first US bombing raid on Afghanistan the Taliban were gone, far quicker than Pentagon estimates. They had been driven out by a combination of American B52 bombers and Afghan fighters from the Northern Alliance, a group of mainly Tajik and Uzbek commanders who had started waging war against the Russians in the 1980s, then continued fighting against the Taliban when they took power in the 1990s.

It was an astonishing success, and seemed like a new model of war. Colin Powell, then US Secretary of State, said: ‘We took a Fourth World army – the Northern Alliance – riding horses, walking, living off the land, and married them up with a First World air force. And it worked.’

The Northern Alliance certainly did not consider itself a Fourth World army, and the fact that there was already a fighting force in place well acquainted with the Taliban was a huge advantage. Based in the picturesque Panjshir valley, they were the fighters of a legendary commander, Ahmat Shah Massoud, a poetic figure with a long, aquiline nose, blue eyes and a rolled felt cap, known as the Lion of Panjshir, whom the Russians had never defeated. Under his leadership the Northern Alliance controlled around 9 per cent of Afghanistan in the north-east – the one bit of the country the Taliban had never managed to conquer.

Massoud’s foreign spokesman was his close friend Dr Abdullah Abdullah, a short, dapper-suited ophthalmologist with a penchant for wide ties. His name was really only Abdullah, as like many Afghans he had just one name, but he had taken another ‘Abdullah’ to accommodate the need of the Western media for surnames. Dr Abdullah had repeatedly travelled to America and Britain, warning that Arab terrorists were taking over Afghanistan. He told me he had made ten trips to Washington between 1996, when the Taliban took power, and 2001 asking for help – all to no avail.4 (#litres_trial_promo) The Americans were not interested in Afghanistan, and had no desire to get involved with a warlord who financed his operations through the trafficking of drugs and lapis lazuli. Massoud was particularly distrusted by the State Department because he received support from Iran and Russia, and because of the fact that he was hated by Pakistan, which the US wanted to keep onside. ‘They just said it was an internal ethnic conflict,’ said Dr Abdullah. Massoud himself spoke at the European Parliament in April 2001, appealing for humanitarian aid for his people and warning that al Qaeda was planning an attack on US soil.

He was hardly a lone voice. George Tenet, who was Director of the CIA at the time, later testified before the 9/11 Commission that the Agency had picked up reports of possible attacks on the United States in June, and said the ‘system was blinking red’ from July 2001. On 12 July Tenet went to Capitol Hill to provide a top-secret briefing for Senators about the rising threat from Osama bin Laden. Only a handful of Senators turned up in S-407, the secure conference room. The CIA Director told them that an attack was not a question of if, but when.

Another warning came in the first meeting between President George W. Bush and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin in a Slovenian castle in July 2001, the American President was taken aback when the former KGB man suddenly raised the subject of Pakistan. ‘He excoriated the Musharraf regime for its support of extremists and for the connections of the Pakistani army and intelligence services to the Taliban and al Qaeda,’ recalled Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s National Security Adviser, who was present. ‘Those extremists were all being funded by Saudi Arabia, he said, and it was only a matter of time until it resulted in a major catastrophe.’5 (#litres_trial_promo)

This was written off as Soviet sour grapes for having lost in Afghanistan. No notice was taken, nor was the Northern Alliance provided with help. It says something about Massoud’s charisma that without Western assistance or much hope of success, he kept his fighters together. ‘He always wore a pakoul [wool cap], and he’d say, “Even if this pakoul is all that remains of Afghanistan I will fight for it,”’ said Ayub Solangi, who had fought with him since the age of sixteen, and had lost all his teeth in torture in Russian prisons.

Two days before 9/11, two Tunisians posing as TV journalists came to his Panjshir headquarters to do an interview. ‘Why do you hate bin Laden?’ they asked him, just before their camera exploded in a blue flash. The assassination of the Taliban’s biggest enemy was widely assumed to be a gift from al Qaeda to their Taliban hosts, to ensure their support as the Bush administration wreaked its inevitable revenge on Afghanistan for blowing up the Twin Towers.

2

Sixty Words (#ue110efdd-99ae-5c21-ae82-f889fc3c445e)

Before exacting revenge, the Bush administration wanted Congressional approval, as under the United States Constitution only Congress can authorise war. So just twenty-four hours after the second plane hit the South Tower, while most people were still trying to digest what had happened, White House lawyer Timothy Flanigan was already sitting at his computer urgently typing up legal justification for action against those responsible.

The last time the US had declared war was in 1991 against Iraq, so he first cut and pasted the wording from the authorisation for that. However, the problem was that this time no one really knew who or where the enemy was, so something wider and more nebulous was needed.

By 13 September Flanigan and his colleagues had come up with the Authorisation for Use of Military Force, or AUMF, for Congress to vote on. At its core was a single sixty-word sentence: ‘That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.’

In other words, this would be war with no restraints of time, location or means.

At 10.16 a.m. on 14 September, the AUMF went to the Senate. The nation wanted action, and all ninety-eight Senators on the floor voted Yes. From there they were bussed straight to Washington’s multi-spired and gargoyled National Cathedral for a noontime prayer meeting called by the White House for the victims of the attacks. It was a highly charged service, with many tears, prayers, a thundering organ and an address by President Bush, followed by the singing of ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’. Members of Congress were then bussed to the House for their vote. One after another called for unity. Four hundred and twenty voted in favour, and just one against. Barbara Lee, a Democratic Congresswoman from California, was as heartbroken as anyone by 9/11 – her Chief of Staff had lost his cousin on one of the flights. But she worried that what she called ‘those sixty horrible words’ could lead to ‘open-ended war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target’. So to the outrage of her colleagues, she stood up and voted No. Her voice cracking, she cried as she asked people to ‘think through the implications of our actions today so this does not spiral out of control’. She ended by echoing the words of one of the priests in the cathedral: ‘As we act let us not become the evil we deplore.’

By the time of the vote, I was on a plane. International air traffic had reopened on 13 September after an unprecedented closing of the skies. Most journalists headed to northern Afghanistan to join up with the Northern Alliance, or to Peshawar in north-west Pakistan, the closest Pakistani city to the border with Afghanistan, and the headquarters of the mujaheddin during the war against the Russians. I headed further west, to the earthquake-prone town of Quetta, which was the nearest Pakistani city to Kandahar, the heartland of the Taliban, and like Peshawar had long been home to hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees. It was also where my oldest Afghan friend, Hamid Karzai, lived.

I checked into the Serena Hotel, where there were soon so many journalists that makeshift beds were set up in the ballroom. I was happy to be back. From my window I could see hills the colour of lion-skin, populated with tribes so troublesome that the British Raj had given up trying to control them and instead given them guns and cash to leave them alone. Beyond those hills lay Afghanistan.

The town used to be on the overland route for backpackers, and in the 1980s I would see big orange double-decker buses that had come all the way from London’s Victoria station. The buses did not come any more, but little else had changed. On the main Jinnah Road you could still buy a rifle or some jewelled Baluch sandals, both of which were sported by the local men who wandered around hand in hand.

I met up with commanders I had known back in the 1980s when they were young, dashing and full of hope. Now they were potbellied, greying and jaded, but they had been given a sudden lease of life by finding their long-forgotten country the focus of world attention. Just as in the old days we sat cross-legged on cushions on the floor drinking rounds of green tea, served with little glass dishes of boiled sweets (in place of sugar) and crunchy almonds.

The most important call of all my old contacts was Karzai, whom I had got to know when we lived near each other in Peshawar and he was spokesman for the smallest of the seven mujaheddin groups fighting the Russians. His family were prominent landowners from the grape-growing village of Karz, near Kandahar. His father had been Deputy Speaker of parliament, and his grandfather Deputy Speaker of the senate; they were from the majority Pashtun tribe, the same Popolzai branch of the royal family as the unfortunate murdered King Shah Shuja. Karzai had been at school in the Indian hill city of Simla when the Russians invaded, and would never forget the moment his schoolfriends gave him the news. ‘I felt I could no longer hold my head high as a proud Afghan,’ he told me. Though he was the youngest of six brothers, he became spokesman for the family as the only one to stay after the others moved to America and opened a chain of Afghan restaurants called ‘Helmand’ in Baltimore, Boston and San Francisco.

‘If you want to understand Afghanistan you must understand the tribes,’ he urged me on our very first meeting. He invited me to his home to meet elders from across southern Afghanistan who soon had me spellbound with astonishing stories that mostly involved fighting and feuding.

Karzai insisted that the key city of Afghanistan was Kandahar, where its first King, Ahmat Shah Durrani, had been crowned. He took me on my first trip there in 1988, the only time he had gone on jihad, when we rode around on motorbikes and had several narrow escapes from Soviet bombs and tanks. The group we had travelled with, the Mullahs’ Front, went on to become Taliban.

A year after that trip the last Soviet soldier crossed the Oxus River out of Afghanistan, but what seemed an astonishing victory quickly soured as the Afghan mujaheddin all started fighting each other. I moved on to other stories in other countries and continents that didn’t bruise my heartstrings quite as much. I still went back and forth to Pakistan, however, and had last seen Karzai in 1996, when we quarrelled bitterly in Luna Caprese, the only Italian restaurant in Islamabad after he told me he was fundraising for the Taliban.

Later he had turned against them, saying Pakistanis had taken over the Taliban and Arabs had taken over the country, and like Dr Abdullah he kept banging on offices in Whitehall and Washington with Cassandra-like warnings. For years, he too had met only closed doors. The British Foreign Office didn’t even have an Afghan section, and a diplomat in the South Asia section told me Karzai would be palmed off with the most junior official, who would moan, ‘Not him again.’

He moved to Quetta, to the house of his genial half-brother Ahmed Wali, who had supported him through all those years when everyone else had forgotten Afghanistan. Now, of course, everything had changed. As a fluent and eloquent English speaker he had a queue of diplomats, spies and journalists at his, or rather Ahmed Wali’s, door.

Karzai greeted me warmly. His father had been assassinated in 1999 by men on motorbikes as he was walking back from prayers at the mosque around the corner from the house. Karzai blamed the Taliban and Pakistan’s powerful military intelligence agency, ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence). He had become head of the tribe after that and needed a wife, so in a betrothal arranged by his mother he married his cousin Zeenat, a gynaecologist at Quetta hospital.

He was shocked by 9/11. ‘If only people had listened,’ he said.‘Everything will change now,’ I replied.

Some things, it seemed, hadn’t changed. Back in the 1980s we had endlessly discussed how ISI were pulling the wool over the eyes of the CIA, which had given them carte blanche to distribute billions of American and Saudi dollars and weapons to the mujaheddin fighting the Russians. Karzai and other Afghans had not forgiven ISI for the way they directed the vast majority to their favourites, the fundamentalist Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Jalaluddin Haqqani, or diverted it to fund their own proxy war in Kashmir as well as build their nuclear bomb. In those days they didn’t really hide this, and I’d even been to visit one of their militant training camps just outside Rawalpindi. Their openness had some limits. In 1990, when I wrote stories that Karzai had helped me research on ISI’s interference and on selling arms to Iran, I had been picked up from my apartment in Islamabad, threatened and interrogated by ISI for a night, followed for a week by two cars and a red motorbike, even to a friend’s wedding, then eventually deported.

Now over green tea Karzai insisted that Pakistan was again lying to the US. ‘They are saying they have stopped supporting the Taliban because otherwise the US will declare them a terrorist sponsor state and bomb them too,’ he said. ‘The Americans told them you are either with us or against us. But you and I know it’s an ideology, not just a policy. I promise you they are still supplying arms to the Taliban.’

To start with, I wasn’t sure I believed him. The eyes of the world were on this region. Surely Pakistan would not be so reckless. But I did know that they had got away with it before, and how personally involved many ISI officers in the field were with some of the Taliban after more than twenty years of working with them. I’d had enough discussions with them to agree with Karzai that for many it was an ideology, not a policy – some told me they saw the Taliban as a pure form of Islam, and would like a similar government in Pakistan.

Some strange things were happening. Shortly after 9/11, when President George W. Bush had asked Pakistan’s military ruler General Pervez Musharraf for cooperation, Musharraf had asked that the US hold off any action until Pakistan had made a last try at persuading the Taliban to hand over bin Laden. General Mahmood Ahmed, the ISI chief, who had helped to organise the coup that brought Musharraf to power, led a delegation of clerics to Kandahar to personally appeal to Mullah Omar. But Mufti Jamal, one of the clerics who went with him, told me that the General made no such request. ‘He shook hands very firmly with Mullah Omar and offered to help, then later even made another secret mission without Musharraf’s knowledge.’

It seemed ISI had calculated that however the Americans retaliated in Afghanistan, they would eventually lose patience, and like all foreigners before them be driven out. ‘We knew the Americans could not win militarily in Afghanistan,’ I was told by General Ehsan ul Haq, who later replaced Mahmood as ISI chief. Pakistan would, however, still be next-door, so it was understandably hedging its bets. ‘The Americans forget other people have national interests too,’ said Maleeha Lodhi, then Pakistan’s Ambassador to Washington.

From Quetta I went to Rawalpindi to see General Hamid Gul, who had been head of ISI when I lived in Pakistan, running the Afghan jihad. He was virulently anti-American, blaming the US for his dismissal in May 1989. It was the first time I had spoken to him since my deportation, and he insisted to me that the people who had abducted and interrogated me were ‘rogue agents’. He still lived in an army house, and somehow it seemed to me that he was still involved. He had personally known bin Laden, and encouraged Arabs to come and fight against the Russians in Afghanistan, setting up reception committees, which as he said the CIA was very happy to use at the time. Indeed, on his mantelpiece was a piece of the Berlin Wall sent to him by German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. It was inscribed: ‘With deepest respect to Lt Gen Hamid Gul who helped deliver the first blow.’ ‘You in the West think you can use these fundamentalists as cannon fodder and abandon them, but it will come back to haunt you,’ he had told me in a rare interview just after the Soviet withdrawal. At the time I had not understood what he meant.

General Gul insisted that 9/11 was orchestrated not by bin Laden but Mossad, the Israeli spy agency, to set the West against Muslims and provide an excuse to launch a new Christian Crusade. ‘No Jews went to work in the World Trade Center that day,’ he claimed. He was dismissive about the latest foreigners to enter Afghanistan. ‘The Russians lost in ten years, the Americans will lose in five,’ he said. ‘They are chocolate-cream soldiers, they can’t take casualties. As soon as body bags start going back, all this “Go get him” type of mood will subside.’

Meanwhile, we waited. War had come to America, 3,000 people had been killed in the Twin Towers, and we knew the US administration would soon retaliate. ‘My blood was boiling,’ Bush later wrote in his memoir. ‘We were going to find out who did this and kick their ass.’ In a televised address to both houses of Congress nine days after 9/11, he told the nation that ‘every necessary weapon of war’ would be used to ‘disrupt and defeat the global terror network’. He warned that ‘Americans should not expect one battle, but a lengthy campaign unlike any other we have ever seen.’

There was one problem. When 9/11 happened, the CIA did not have a single agent in Afghanistan. Only a handful had been there in the previous decade, and they were in the north. The CIA had no contacts among Pashtuns in the south. The FBI had only one officer dedicated to bin Laden. At Fort Bragg the top US special forces continued to be taught Russian, as if the Cold War had not gone away.

While journalists quickly found their way into Northern Alliance strongholds, renting all the available cars and houses, the military took much longer to arrive. The first Americans into Afghanistan after the journalists were a CIA team headed by a man who, at fifty-nine, had thought his days in the field were long over. One of the few agents to have gone to Afghanistan in recent years, Gary Schroen had been involved with Afghanistan on and off since 1978, and had close contacts with the Northern Alliance. He was preparing for retirement when he was called up by the Counter-Terrorism Center (CTC), much to his wife’s annoyance. Seventeen days after 9/11 his seven-man team were on an old Russian helicopter into the Panjshir valley to link up with the Northern Alliance.

Apart from communications equipment, the most important part of their baggage was a large black suitcase containing $3 million in cash. On the first night they gave $500,000 to Engineer Aref, intelligence chief for the Northern Alliance, followed by $1 million the next day to Marshal Fahim, who had succeeded Ahmat Shah Massoud as military commander. More money was sent, and within a month they had handed out $4.9 million.

The plan was to send teams of US special forces to join up with Afghan commanders. The Americans would then direct airstrikes using SOFLAMs (Special Operations Forces Laser Acquisition Markers) to pinpoint targets. They also had GPS systems to provide coordinates, as these could be used in all weathers. B52s would then fly over and drop 2,000-pound smart bombs, which would pulverise the target.

However, when the bombing started, almost a month after 9/11, bureaucratic delays and infighting in Washington meant there was still not a single US soldier inside Afghanistan. The only on-the-ground information was coming from Schroen’s CIA team and the Afghans.

From the start there was friction. America wanted intelligence on al Qaeda safe houses and camps, and most of all they wanted the man behind 9/11. Before he had left the US, Schroen’s boss Cofer Black had told him, ‘I want you to cut bin Laden’s head off, put it on dry ice, and send it back to me so I can show the President.’ The Northern Alliance commanders were more interested in targeting Taliban front lines so they could advance on Kabul and take power.

On Friday, 7 October, President Bush stood in the Treaty Room of the White House and addressed America, announcing the launch of Operation Ultimate Justice (which was quickly renamed Operation Enduring Freedom). A few hours earlier – night-time in Afghanistan – an awe-inspiring fleet of seventeen B1, B2 and B52 bombers had taken off from bases in Missouri and Diego Garcia to drop their bombs on one of the poorest places on earth. Alongside them were twenty-five F14 and F18 fighter jets flown off the decks of aircraft carriers USS Enterprise and USS Carl Vinson in the Arabian Sea. Fifty Tomahawk missiles were launched from American ships and a British nuclear submarine. Several had been painted with the letters ‘FDNY’ – Fire Department of New York – in remembrance of the firefighters who lost their lives trying to rescue victims at the Twin Towers. The heaviest bombing that night was carried out by the B52s, which rained 2,000-pound JDAMs as well as hundreds of unguided bombs aimed at taking out the Taliban air force and suspected al Qaeda training camps in eastern Afghanistan. That first night they struck thirty-one targets.1 (#litres_trial_promo) The US State Department sent a cable to Mullah Omar via Pakistan informing him that ‘every pillar of the Taliban regime will be destroyed’.

In my hotel room in Quetta I watched on CNN the Pentagon videos of the planes setting off on the bombing raids, and the flashes as targets were hit. Taken on night-vision cameras, the footage was green, with a ticking digital timer running at the bottom, and looked like a video game. I wondered what the Americans could bomb in that country of ruins, with no real infrastructure. Soon they found themselves running out of targets. All the air power in the world was of little use when what they were really fighting was an ideology, not a conventional army.

Our own movements were curtailed by Pakistani minders. For our ‘security’ we were not allowed out of the hotel without the company of one of the ISI agents who frequented the lobby. I’d found a Fuji photographic shop that had a back door into the market through which I could be met by an old friend. He would whisk me off to meet tribal elders or Afghan commanders so they could speak freely while my minder was watching TV in the Fuji shop. I knew I was testing their patience, so sometimes I met people in what we called ‘Nuclear Mountain Park’ – its centrepiece was a model of Chagai in the Baluch hills, where Pakistan had carried out its first nuclear tests three years earlier on what was referred to as ‘Yaum-e-Takbeer’, or Allah’s Greatness Day. Every evening people came out to walk round and round the model nuclear mountain, eating ice creams from a cart decorated with red-tipped rockets.

When the US bombing started across the border there were riots in Quetta, and anything perceived as Western was attacked. In Quetta this was not a lot – basically the cinema and the HSBC bank, which had its cashpoint ripped out of the wall, causing untold inconvenience to us correspondents, as it was the only one. The protests gave ISI an excuse to lock us in the hotel altogether, on the grounds that it was too dangerous for us to venture out.