По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

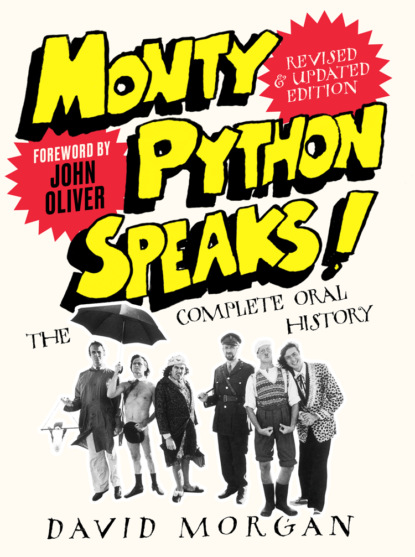

Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The executive producer of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Goldstone was the producer of Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life. He also co-produced quasi-Python projects such as Terry Jones’ The Wind in the Willows.

MARK FORSTATER

A flatmate of Terry Gilliam’s in New York City in the 1960s, Forstater served as producer of Monty Python and the Holy Grail. His other film and TV credits include The Odd Job, The Fantasist, and Grushko.

JULIAN DOYLE

Doyle’s duties as production manager on Holy Grail included staging the Black Knight sequence in East London, locating a Polish engineer in the wilds of Scotland to fashion a cog for a broken camera, and transporting a dead sheep in his van at five o’clock in the morning. He took the more sedate job of editor for Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life. He has also edited Brazil and The Wind in the Willows.

TERRY BEDFORD

Director of photography for Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Bedford also served as DP for Terry Gilliam’s Jabberwocky. He has since become a director for television and commercials, and helmed the feature Slayground.

HOWARD ATHERTON

A fellow alumnus of the London International Film School with Bedford, Doyle, and Forstater, Atherton was camera operator on Holy Grail. He has served as director of photography for such directors as Adrian Lyne (Fatal Attraction, Lolita) and Michael Bay (Bad Boys).

NANCY LEWIS

Python’s New York-based publicist and, later, personal manager during the Seventies and Eighties.

DOUGLAS ADAMS

Not a Python, but an incredible simulation. Before creating The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Adams collaborated with Graham Chapman in the mid-Seventies, and even contributed a few morsels to Python. He later collaborated with Terry Jones and John Cleese on the video game Starship Titanic. (Adams died in 2001.)

HANK AZARIA

A six-time Emmy Award winner, Azaria has appeared in the Mike Nichols film The Birdcage, Cradle Will Rock, Mystery Men, and Tuesdays with Morrie, and the series Mad About You, Huff, Ray Donovan, and Brockmire. But he is probably best known as the voices of Moe, Chief Wiggum, Apu, Comic Book Guy, and several dozen other characters on The Simpsons. Azaria was a Tony Award nominee for the original Broadway production of Monty Python’s Spamalot.

INTRODUCTION (#ue8ca10d0-2b7c-5fe0-befb-0ed9bff34644)

This revolution was televised.

When the six members of Monty Python embarked on their unique collaboration fifty years ago, they were reacting against what they saw as the staid, predictable formats of other comedy programmes. What they brought to their audience was writing that was both highly intelligent and silly. The shows contained visual humour with a quirky style, and boisterous performances that seemed to celebrate the group’s creative freedom. But what made Monty Python extraordinary from the very beginning was their total lack of predictability, revelling in a stream-of-consciousness display of nonsense, satire, sex, and violence. Throughout their careers they were uncompromising in their work, and consequently made a mark on popular culture – and the pop culture industry – which is still being felt today.

Two of the more revolutionary concepts of Monty Python’s Flying Circus (the BBC Television series which premiered in Britain in 1969 and in the United States five years later) were the lack of a ‘star’ personality (around whom a show might have been constructed), and the absence of a specific formula. Typically, the most popular or influential comic artists in film or television were those who had shaped a powerful persona, either of themselves or of an archetypal character. Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, the Marx Brothers, W. C. Fields, Bob Hope, Woody Allen, and Richard Pryor all worked within a formula in which the comedy would be built around a recognizable character. And while a few experimented with the conventions of motion pictures (such as Allen’s character Alvy Singer breaking the fourth wall while standing in a cinema line in Annie Hall), it was still in support of a comic personality.

Television (and radio) also perpetuated the situation comedy, in which narrative possibilities were limited by being subordinate to the conventions of already-accepted characters, with no deviation allowed. Even Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, which was heralded in its time for its fast, freewheeling format, nonetheless had a format, in addition to recurring characters and situations.

Python would have none of that. Apart from a few repeated characterizations such as the Gumbys (irrepressible idiots, which were themselves pretty vaguely drawn), the series’ forty-five episodes marked a constant reinvention. Each production had its own shape, with only rare reminders of what other Python shows were about. There might be a theme to a particular episode’s contents, but even that was a pretty loose excuse for linking sketches together. It was that fluidity of style that made the Pythons seem like a rugby team which kept changing the ground rules and moving the goalposts, and still played a smashing good game – one could barely keep up with them. And even as audiences became more familiar with each Python’s on-screen personality, the six writer/performers were so adaptable and chameleonic that no one ever stood out as the star of the group – the cast was as fluid as the material.

This very flow of action and ideas was the most potent source of humour for Python. The comedy had an inner logic (or illogic) that was not contingent upon generally accepted notions of drama: there was no narrative drive, no three-act structure, and no character development (and in fact, there was often anti-character development, as when the camera turns away from a couple deemed ‘the sort of people to whom nothing extraordinary ever happened’).

As the series progressed, the troupe experimented with doing longer and longer sketches, or (as in ‘Dennis Moore’) creating characters or situations which would reappear at different points throughout the show. By the end, a couple of episodes (‘The Cycling Tour’, ‘Mr Neutron’) were in effect half-hour skits, though their lack of dramatic arc pointed to the fact that separate, disparate sketches were in effect draped over a specific character serving as a linking device.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus never had the tight adherence to form or place that John Cleese’s Fawlty Towers had, and never really told a story, as the Michael Palin and Terry Jones series Ripping Yarns did. What it did have were odd and surreal juxtapositions, a penchant for twisted violence, and a belief that the human condition is, on the whole, pretty absurd.

The films that followed – Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Life of Brian, and The Meaning of Life – demonstrated quite vividly that this stream-of-consciousness approach could be transferred to feature-length films, but the Pythons also showed that they could (when they wanted to) have the discipline to tell an actual story. Brian is a fast-moving, fully formed tale whose comic asides never distract from the central figure’s arc. More importantly, the filmmakers offer some serious social commentary mixed in with the humour, without ever seeming pedantic or boring – a very rare talent.

Python was not about jokes; it was really about a state of mind. It was a way of looking at the world as a place where walking like a contortionist is not only considered normal but is rewarded with government funding; where people speak in anagrams; where highwaymen redistribute wealth in floral currencies; and where BBC newsreaders use arcane hand signals when announcing the day’s events. And as long as the world itself is accepted as being an absurd place, Python will seem right at home. That is why the shows and films remain funny to audiences fifty years after their premiere, even after the routines have been memorized.

Monty Python Speaks! explores the world of the Pythons, who describe in their own words their coming together, their collaboration, their struggles to maintain artistic control over their work, and their efforts to expand themselves creatively in other media. It also documents the stamp they have made on humour; the passion of their fans; and the lasting appeal of their television and film work, books, recordings, and stage shows, in Britain and around the world. It also reveals what is perhaps the definitive meaning of ‘Splunge!’

And now, ‘It’s …’

PRE-PYTHON (#ue8ca10d0-2b7c-5fe0-befb-0ed9bff34644)

IN THE OLD DAYS WE USED TO MAKE OUR OWN FUN

If there is a progenitor to credit (or blame!) for Monty Python, the innovative and surreal comedy group that turned the BBC and cinema screens on their ends, one need look no further than a tall, undisciplined, manic-depressive Irishman, born and raised in India, who spent his young adulthood playing the trumpet for British troops in North Africa, before wrestling his fervent notions of humour onto paper in the back of a London pub.

Spike Milligan, author of such pithy memoirs as Adolf Hitler – My Part in His Downfall, created the revolutionary BBC Radio series The Goon Show, which was to radio comedy what Picasso was to postcards. Aired between 1951 and 1960, and featuring Milligan, Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe, and (briefly) Michael Bentine, The Goon Show was a marvellously anarchic mixture of nonsensical characters, banterish wordplay, and weird sound effects all pitched at high speed. The surreal plots (such as they were) might concern climbing to the summit of Mt Everest from the inside, drinking the contents of Loch Lomond to recover a sunken treasure, or flying the Albert Memorial to the moon.

Milligan’s deft use of language and sound effects to create surreal mindscapes showed how the medium of radio could be used to tell stories that did not rely on straightforward plots or punchlines; it was the illogic of the character’s actions bordering on the fantastic (e.g., the hero being turned into a liquid and drunk) which moved the show along. It was a modern, dramatized version of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear – fast-paced and hip, its language a bit blue around the edges.

The artistic and popular success of The Goon Show inspired many humourists who followed. Although its surreal nature could not really be matched, its fast-paced celebration of illogic and its penchant for satire opened the doors for some of the edgier comedy that came to light in Britain in the Sixties, such as Beyond the Fringe (an internationally successful cabaret featuring Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller, Alan Bennett, and Dudley Moore), and the television series That Was the Week That Was and The Frost Report.

But while The Goon Show demonstrated how broadcast comedy could bend convention, it was the passionate satire of the rising talents from university revues that forced satire – typically a literary exercise – into the vernacular of the day. If a map were to be drawn of the comedy universe in the late Fifties and early Sixties, its centre would assuredly comprise the halls of Cambridge and Oxford; between them, they produced a flood of talented writers and performers who were to raise the comedy standard, extending from stage to recordings, magazines, television, and film.

Among the many illustrious figures who began their careers in the Cambridge Footlights comedy troupe or in revues at Oxford were Humphrey Barclay, David Frost, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Bill Oddie, Graeme Garden, Jo Kendall, David Hatch, Jonathan Lynn, Tony Hendra, and Trevor Nunn. Also from this rich training ground came five writer/performers of deft talent: Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin – five-sixths of what would become the most successful comedy group in film and television, Monty Python.

Leading up to their first collaboration as Python in the spring of 1969, these five Cambridge/Oxford university graduates were working separately or in teams for several radio and TV shows at the BBC and at independent television (ITV) companies. They soon recognized similar tastes or aesthetics about how comedy should be written and performed. It was partly magnetism and partly luck which brought the group together, and the result was a programme that reinvented television comedy, launched a successful string of films, books, and recordings, and turned dead parrots and Spam into cherished comic icons.

I MEAN, THEY THINK WELL, DON’T THEY

TERRY JONES: Mike and I had done a little bit of work together when we’d been at Oxford. I first saw Mike doing cabaret with Robert Hewison, who later became a theatre critic. Mike and I and Robert all worked together on a thing called Hang Down Your Head and Die. It was in the style of Joan Littlewood’s Oh, What a Lovely War, and it was a show against capital punishment, which we still had in this country at that time. That was the first time Mike and I worked together. And then we did an Oxford revue called Loitering Within Tent – it was a revue done in a tent – and he and I worked out a sequence called the ‘Slapstick Sequence’ [in which a professor introduces demonstrations of various laugh-inducing pratfalls]. As far as I remember that was the first real writing collaboration we did, and in fact that sketch was later done in the Python stage show.

I did a bit of writing with Miles Kington (who was a columnist for The Independent), and then when Mike came down (I was a year ahead of Mike) he worked on a TV pop show for a while. By that time I’d got a job at the BBC, so I kind of knew what was happening, and Mike and I started writing stuff for The Frost Report. We were contributing little one-liners for Frost’s monologue and sketches, and then we got to doing these little visual films which we actually got to perform in. Little things like, ‘What judges do at the high court during recess’. We just filmed a lot of judges with their wigs and gowns in a children’s playground, going down slides.

We weren’t being paid very much for the writing; our fee in those days was seven guineas a minute – of course, that’s a minute of airtime, not how long it takes to write! We were kind of lucky [if] we got two or three minutes of material on the show, so by letting us appear in our little visual films, it meant that they could pay us a bit more.

MICHAEL PALIN: Terry and I worked together since I left Oxford, which would be 1965. Terry by that time had a job in the BBC in a script department, and we worked together very closely. We saw each other on an almost daily basis, and that was true from that period right up to the Python times; we wrote for all sorts of shows, tons and tons of stuff.

Apart from your collaboration with Terry,

were you also writing on your own?

PALIN: Not really, there wasn’t time. We had to make money in those days, too. We’d just got married and [were] having children and all that sort of thing. I probably had days when I thought, ‘Today I’m going to start The Novel,’ or whatever. And then we’d be offered by Marty Feldman a hundred pounds a minute for this new sketch (that’s between the two of us). ‘A hundred pounds a minute? I don’t believe that, that’s fantastic, so we better write something for Marty!’ So that day would be spent writing something for Marty Feldman. So yeah, we were real genuine writers during that time, we worked as a team. Although the mechanics of writing were not necessarily that we would sit in the same room with a giant piece of paper and say, ‘All right, now we’re going to make a sketch.’

JONES: Originally when we’d been writing for The Frost Report and for Marty Feldman, Mike and I would go and read them through, they’d all laugh, the sketch would get in, and then you see the sketch on the air and they fucking changed it all! We’d get furious. There was one sketch Marty did about a gnome going into a mortgage office to try to raise a mortgage. And he comes in and sits down and talks very sensibly about collateral and everything, and eventually the mortgage guy says, ‘Well, what’s the property?’ And he says, ‘Oh, it’s the magic oak tree in Dingly Dell.’ And the thing went back and forth like that. Everybody laughed when we did it, and when we saw it finally come out on TV, Marty comes in, sits cross-legged on the desk, and starts telling a string of one-line gnome jokes. This wasn’t what the joke was at all.

What happens is that people (especially someone like Marty) would start rehearsing it, and of course after you’ve been rehearsing it a few times people don’t laugh anymore. And so Marty being the kind of character he was, he’d throw in a few jokes, and everybody would laugh again. And so that’s how things would accumulate. It was things like that that made us want to perform our own stuff. We sort of felt if it worked, you wanted to leave it as it was.

Humphrey Barclay

asked if Mike and I would like to get together and do a children’s show with Eric Idle. We’d seen Eric in Edinburgh in my final year in the Cambridge revue, a young blue-eyed boy; he looked very glamorous on the stage as I remember! So we knew of Eric, but we’d never worked with him. The three of us wrote Do Not Adjust Your Set. It was basically a children’s TV show but we thought, ‘Well, we’ll just do whatever we think is funny, we won’t write specifically for children.’ And we had the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band in it.

And then at the same time we were doing the second series of Do Not Adjust Your Set, Mike and I were also doing The Complete and Utter History of Britain for London Weekend Television.