По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

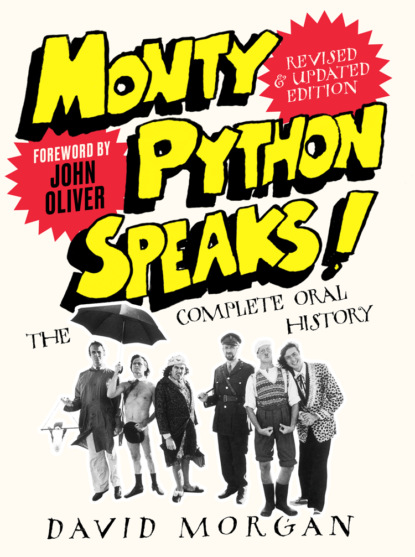

Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

PALIN:The Complete and Utter History had a narrative [like] a television news programme. You had someone in the studio describing events that were going on, and then the camera would go out ‘live’ to, for instance, the shower room leading out to the Battle of Hastings where all the teams were washing, cleaning themselves off, and talking about the battle, as if it were a current affairs show in 1066 or 1285 or 1415. It was a very simple set-up. So we could parody television a little bit, but on the other hand we had to accept the convention of a television show, which made it a much more regular shape.

JONES: My big hero is Buster Keaton because he made comedy look beautiful; he took it seriously. He didn’t say, ‘Oh, it’s comedy, so we don’t need to bother about the way it looks.’ The way it looks is crucial, particularly because we were doing silly stuff. It had to have an integrity to it.

One time on The Complete and Utter History, we were shooting the Battle of Harfleur, the English against the French, and we wanted to shoot it like a Western. It was parodying Westerns where you see the Indians up on the skyline; when you come closer they’re actually Frenchmen with striped shirts and berets and baguettes and bicycles and onions, things like that. And then the Frenchmen breathe on the English: ‘They’re using garlic, chaps!’ And the English all come out with gas masks. All pretty stupid stuff. But it was very important that it should look right.

Anyway we turned up on the location to shoot it, looking around with the director, actually it was a nice gentle bit of rolling countryside amongst the woods. I said, ‘Where’s the skyline? There isn’t a skyline, doesn’t look like America, it looks like English countryside.’ We were there, we had to shoot it, but it wasn’t the thing we meant to be shooting. It wasn’t a Western parody – that element was missing from it – so it looked like just a lot of silly goings-on in front of the camera. And it was at that moment when I realized you can’t just write it, you can’t just perform it, you’ve actually got to be there, looking at the locations, checking on the costumes – everything was crucial for the jokes.

Curiously, we thought Complete and Utter History was wiped.

The only things that existed of that were the 16-millimetre film inserts which I collected, but in fact a couple of years ago somebody turned up a whole programme that had been misfiled. All the stuff filed under ‘Comedy’ had been wiped, but this was filed under ‘History’ and so it was still there! But it was quite odd seeing it again, after all those years, and how Pythonic it was, way more so than Do Not Adjust Your Set.

Terry Jones in The Complete and Utter History of Britain.

NOW WHICH ONE OF YOU IS THE SURGEON?

John Cleese and Graham Chapman met in the Footlights club at Cambridge, where they were studying law and medicine, respectively. Cleese had originally gone to university for science, but upon realizing it wasn’t for him, he found his choices limited to archaeology and anthropology (‘which no serious-minded boy from Weston-super-Mare would waste a university education on’), economics (‘which I couldn’t think of anything much more dreadful to study’), and law.

JOHN CLEESE: Graham and I met at Cambridge when we were both auditioning for a Footlights show, which would have been 1961, and we both auditioned unsuccessfully. And we went and had a coffee afterwards and the funny thing is I remember that I quite disliked him, which is not a reaction I have to most people. But it was odd that that was my first reaction to him. It was purely intuitive.

What I liked about Footlights (which numbered about sixty) is there was a wider cross-section, so you got English people but you also got scientists, historians, and psychologists. Also, there was much more of a mix of class. A lot of the other clubs tended to have a predominant class or predominant attitude; the Footlights crowd were very mixed and very good company, very amusing, and a lot less intense and serious and dedicated than the drama societies, who (it seemed to us) took themselves a bit seriously.

At the beginning of the following university year, a number of us arrived back at Cambridge and we went to the Footlights club room and in bewilderment we saw a notice board informing us that we were now officers! We had been in the club for such a short period of time that we’d not realized that almost everyone in the club had left the previous year. So I found myself registrar, Tim Brooke-Taylor was junior treasurer, Graham was on the committee, we all had these jobs (without having the slightest idea what they entailed), but it meant that we got pushed together because we had to run the club.

Chapman and Cleese and friends.

So I got to know Graham. And he and I (and I don’t remember how) started to write together, and most of the things I wrote at Cambridge after I met Graham were written with Graham.

And then at the end of that year he went to London to continue his medical studies at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. He used to do some moonlighting, a late-night revue (which I never saw) with a guy called Tony Hendra, in a little room above the Royal Court Theatre. Graham used to come up to Cambridge occasionally and we continued to write a bit. And then when the Footlights Revue of 1963, A Clump of Plinths, started, Chapman used to come and watch and I used to make him laugh!

Then on the opening couple of weeks two very nice men in grey suits, Ted Taylor and Peter Titheradge, turned up at Cambridge. They’d noticed that I’d written a large portion of the material and they offered me a job. I was never very committed to being a lawyer, so when these guys offered me £30 a week when I was facing two and a half years in a solicitor’s office where I was going to get £12 a week (which was not much money even in 1963), I took the BBC job. I wasn’t at all sorry to say good-bye to the law; it was easy to convince my parents that it was okay because this was the BBC so there was a pension scheme – it was almost like going into the entertainment branch of the civil service.

Later when the Footlights Revue (which obviously didn’t have Graham in it) transferred to London, Anthony Buffery did not want to stay with the show very long, and his place was taken by Graham.

Cambridge Circus, directed by Humphrey Barclay, was a smash in the West End in August 1963. The show featured Chapman, Cleese, and Bill Oddie and Tim Brooke-Taylor (who would later form two-thirds of the Goodies), David Hatch, Jo Kendall, and Chris Stuart-Clark. Cleese followed the stage show with a knockabout radio programme, I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again, which Barclay produced for the BBC. It borrowed not only material from Cambridge Circus butalso several of its stars: Oddie, Brooke-Taylor, Hatch, and Kendall.

CLEESE: That’s what I did for a time until Michael White, the guy who put Cambridge Circus on in London, got in touch with us all about the middle of the following year and said, ‘Would you guys like to come to New Zealand and probably Broadway?’ So we all gave up our jobs and joined up.

Graham interrupted his medical studies. He always had a nice story that the Queen Mother came to St Bart’s around this time to take tea with some of them, and he actually put his quandary in front of her, and said, ‘Should I go on being a medical student or should I go off to do this show in New Zealand and Broadway?’ And she said, ‘Oh, you must travel.’ So he came! We had fun in New Zealand, which was a strange part of the Empire: very refined and very well mannered and sort of stuck around 1910. I remember [in] one town you could not find a restaurant that was open after eight o’clock!

DAVID SHERLOCK: Graham was training at St Bart’s Hospital at the same time that Cleese was still training as a solicitor. A Footlights-type revue was brought every Christmas to the patients in the wards, with all the people Graham worked with – Cleese, Bill Oddie, Jo Kendall, all the cast of Cambridge Circus – moving from ward to ward. Graham often directed; later on, he worked with other young doctors who were equally talented.

Cambridge Circus had so many elements of Python – the anarchic humour, sketches which had no punchline. The New York show was produced by Sol Hurok, who was better known at that period for bringing ballet over to New York (the Royal Ballet, etc.). It turned out these almost-schoolboys were brought over specifically as a tax loss, and on the first night they were given their notice – which is a hell of a way to open in New York, particularly as I think Clive Barnes absolutely raved.

CLEESE: We were always puzzled because it got such good reviews, with the exception of Howard Taubman of the New York Times, the former sportswriter (which I always add!), and it got this terrific review from Walter Kerr, who then – when he heard we were coming off – wrote another to try to boost the audience, which was marvellous. We could never figure out why Hurok had bothered to bring us to New York and put us on, when after we got such good reviews he didn’t bother to publicize the show. Somebody said he was looking for a tax loss and I don’t know whether there was any truth to it, or whether it was the exact truth or whether it was a rumour.

After Broadway, we went and performed at a small theater club off Washington Square called Square East. And after a time we put together a second show, but Graham said, ‘I must be off.’ So he went back to England to continue his studies.

I stayed on, got invited to do Half a Sixpence with Tommy Steele for six months, and tried to have a journalistic career at Newsweek, but my mentor disappeared to cover a crisis in the Dominican Republic so I sort of resigned before I was fired. I did one more show which took me to Chicago and Washington, and then came back to England in the beginning of 1966.

The threads start to come together at the end of 1965. David Frost had called from the airport and said, ‘Would you like to be in a television show? There are two other guys who are very funny but they’re unknowns – Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett – and there’s me, and it’s a sketch show and I’d like you to be in it, and it starts in March.’ And I said, ‘Yes, please!’ I mean, I was astonished, it was just absolutely out of the blue. David was the only person in England who knew my work at all and who was in any position of power to give me a job, so it was very lucky.

While I was in America doing these other things, that’s when they got I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again together on a regular, organized basis, and they did one or two series with Graeme Garden, and when I got back in 1966 they asked me to join the team, and I was very happy to do it. But the big thing was the television show, The Frost Report, for a number of reasons: one was I had never been particularly picked out or noticed as being especially good on stage. The moment I appeared on television something else happened, and I can only assume that some of the acting stuff I did worked better in close-up than it did from the tenth-row stalls. Because the moment I appeared on television there was a bit of a rustle of interest, and I’d got used to there not being a rustle of interest. Because when Cambridge Circus started most of the reviews were garnered by Bill Oddie (who was singing songs which he did very, very well, and he also had a couple of very amusing parts like a dwarf in a courtroom sketch), and the next most successful guy was Tim Brooke-Taylor (who had two or three big funny set pieces). I picked up a few reviews along with David Hatch, but I was not singled out.

Did Graham write outside of his partnership with John?

SHERLOCK: Graham wrote links for Petula Clark when she was doing her early Sixties television show over here. Petula Clark, while being a wonderful singer, could not ad-lib at all. She was very frightened about opening her mouth on stage and not knowing what to say. So everything had to be scripted, all the links between the songs. So he had a close rapport with Clark, which is very funny, particularly when you see some of the Python sketches later on which reference her.

CLEESE: So I’d got The Frost Report, and sitting at the scriptwriter’s table were five future Pythons: Mike and Terry tended to write visual, fill-in items, which we used to shoot during the course of the week and then they would be edited into the show. And Eric typically used to write monologues which Ronnie Barker often did. So the show frequently consisted of a filmed item by Mike and Terry, one or two sketches by Graham and me, occasional Ronnie Barker pieces by Eric, and then a lot of other material from another dozen scriptwriters, of whom the leader was Marty Feldman. Graham didn’t perform; Mike and Terry would probably say that he turned up in one of the filmed items at some point, but I don’t remember him.

We did these half-hour shows every week for thirteen weeks, each on a theme. Tony Jay, who founded Video Arts and has been a friend of mine for thirty years, wrote a theme each week – advertising or education or transport. Everybody used to read the theme paper because it was actually insightful and original, and then we completely ignored it! Then, because it had gone well, David Frost said to Tim and me, ‘Would you like to do a show together?’ And we said, ‘Yes, we would,’ and we immediately said we’d do it with Graham, and then we said to Frost that as the fourth member of the team we would like to have Marty Feldman. I remember that David was quite thrown, a little embarrassed, and said, ‘Well, people would be put off by his appearance.’

So Graham and I, along with Tim and Marty, did At Last the 1948 Show, which was very much more way-out than anything we’d done. Some of it was very bizarre and very funny, it was a good little show, done on no money at all. I remember we used to edit the videotape with a razor, literally.

So in my first two years of television, between The Frost Report and At Last the 1948 Show, I did forty television shows, which is quite a lot when you’re contributing as a writer. It was pretty busy. And then I got married to Connie Booth (whom I’d met in New York), and I thought it was not fair for me to spend time in the studios until she got used to London, so I forswore acting, which cost me nothing at all. I’ve never been that attached to acting, and I can easily live without it, it’s just that it pays much better than writing – that’s the problem. And I didn’t in fact perform for really quite a long time, something on the order of eighteen months.

And during that time Graham and I wrote various things; at one point for some reason Graham, Eric, and I wrote most of a special for a very good English comedian, Sheila Hancock. We just did one show – I’ve no idea in retrospect why. And we got to know Peter Sellers. Graham and I wrote two or three screenplays for Sellers, the only one of which that got made was The Magic Christian. We came in on about draft nine of that, did I think a good draft on which they raised the money, and then Terry Southern came back and rewrote it again, and – we thought – made it worse. A certain amount of our stuff survived that, including my scene at Sotheby’s, cutting the nose off the portrait.

Graham and I towards the end of Thursday afternoons formed a habit of turning on the television to watch Do Not Adjust Your Set, which was much the funniest thing on television; although it was thought of as a kids’ show it was really funny stuff. We knew these guys although we had not spent that much time with them, and I picked Palin out as a performer and asked him to be in How to Irritate People, a special produced by Frost.

Mike and I got on very well. I wrote a lot of that with Graham and one or two of the sketches with Connie, like the upper-class couple who can’t say, ‘I love you’; they have to say, ‘One loves one’.

The cast of Do Not Adjust Your Set (clockwise from top left: Idle, Palin, David Jason, Denise Coffey, Jones).

I didn’t enjoy the experience. The recording of it was a nightmare; everything went wrong. I remember starting one sketch and then we had to relight it, we stopped in the middle of the sketch and then started again, and again stopped it and relit it. And the audience had been there so long, about halfway through the recording they started leaving to be able to catch their buses home. I remember standing in front of the camera reading something and thinking, ‘I don’t think I want to do this again as long as I live!’ It was an awful experience. Maybe that helped put me off the acting!

WITH A MELON?

Eric Idle, who was also in Cambridge (and as president of Footlights allowed women in as full members for the first time), appeared onstage in Oh, What a Lovely War, contributed to I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again and The Frost Report, and helped create (with Palin and Jones) Do Not Adjust Your Set and We Have Ways of Making You Laugh.

How familiar were each of you with the other Pythons before the group was formed?

ERIC IDLE: We weren’t new to each other at all. I met Cleese in February 1963 at Cambridge; Jonesy, Edinburgh 1963; Palin, Edinburgh 1964; Chapman, also Cambridge, summer 1963. We had all worked together as writers and actors. Jones, Palin, and I were perhaps the closest, having written two whole seasons of Do Not Adjust Your Set, but I had written six episodes of a sitcom with Graham, and we had all worked together on The Frost Report. So we weren’t new to each other at all, but were actually very familiar; what was new was being free to decide what we wanted to do.

HAVE WE SHOWN ’EM WE GOT TEETH?

The lone American of Python – a native of Minnesota and a product of Los Angeles – Terry Gilliam fled the land of his birth in the late Sixties by turning the advice of Horace Greeley on its end and heading east, first to New York, then London. He worked in magazines as an illustrator and designer, most notably for Help!, published by the creator of Mad magazine, Harvey Kurtzman.

TERRY GILLIAM: I always drew when I was a kid. I did cartoons because they were the most entertaining. It’s easiest to impress people if you draw a funny picture, and I think that was a sort of passport through much of my early life. The only art training I had was in college, where I majored in political science. I took several art courses, drawing classes, and sculpture classes. I’d never taken oil painting, any of those forms of art, and I was always criticized because I kept doing cartoons instead of more serious painting.

My training has actually been fairly sloppy and I’ve been learning about art in retrospect. In college I didn’t take things like art history courses. I didn’t like the professor and it was a terribly boring course, so I didn’t really know that much. But I’ve always just kept my eyes open, and things that I like I am influenced by.

Once I had my little Bolex camera, every Saturday with a three-minute roll of film we’d run out and invent a movie, depending upon what the weather was. I remember doing animation that way as well; we would go around the dustbins and get old bits of film and then we’d scratch on them, each frame, make little animated sequences; it was pathetic! But you were kind of learning something in the course of all this – anger, I think, is what I was learning, hatred for society, and wealth, and powerful people who I’ve never been able to deal with subsequently!

I spent about a year and a half in advertising in Los Angeles. My illustrating days were becoming less and less remunerative, and Joel Siegel (now the famous television critic) was an old friend, in fact the very first cartoon I ever had published was an idea by him. He was working at an ad agency and got me in because I had long hair – the agency needed a longhair in the place – so I became an art director and copywriter. The last job we had there Joel and I were doing advertisements for Universal Pictures, and we hated the job. Richard Widmark did a film called Madigan, and the kinds of things we were throwing back at Universal were: ‘Once he was happy, but now he’s MADIGAN!’

CLEESE: I’d got to know Terry Gilliam in New York a little bit.

He turned up in England out of the blue – must have been 1966 – and I remember having lunch with him when I was doing At Last the 1948 Show. I introduced him to one or two people, including Humphrey Barclay, who was producing Do Not Adjust Your Set. So Humphrey used him on a London Weekend Television show called We Have Ways of Making You Laugh. Terry used to do little sketches, caricatures of guests appearing on the show.