По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

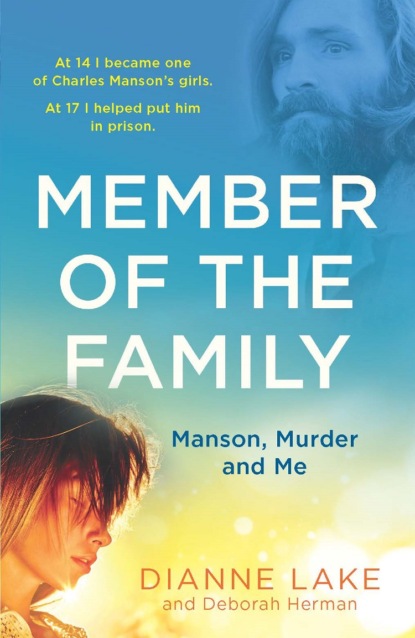

Member of the Family: Manson, Murder and Me

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My resolve didn’t last very long. Later that summer I changed my mind, only this time I knew what was happening. That other person inside of me emerged, the one that had followed Kim Fowley around until he had no choice but to notice me, and that person knew there had to be more to sex than what I’d done under the pier.

It started when I noticed a guy named Kenneth around Venice Beach. Venice was a place where ideas flourished. Hippies flocked there every day to sell their wares, show off their music, or try to influence the masses. Kenneth had set up an event from late July until early August for people to come together to pick up trash on the beach. The idea was to promote environmentalism and ecology. Of course I went to the event and met Kenneth at the table he set up to hand out pamphlets about stopping pollution. He was at least ten years older than I was, which made him even more appealing. He was handsome and he stood for something. He told anyone who would listen how wrong it was to destroy the earth and how we need to teach children when they are at a very impressionable and important time in their lives. We could use their creativity to raise consciousness about ecology. He was an activist who was doing something good with his time, something practical and not simply self-indulgent. I listened to his pitch about not using plastic and other throwaways and positioned myself so eventually he would notice me. He didn’t notice me at first, but I wasn’t deterred. I started hanging out by his table every day, and eventually he started paying attention.

He started the conversation, but I was actively trying to draw him in. He invited me to walk along the beach and I listened to everything he had to say. I don’t remember if he ever asked me anything. I didn’t really care. I wanted him to kiss me, and he finally did on one of the benches behind a palm tree. He took things slowly, and it was obvious he was experienced. When he French-kissed me, I didn’t feel like I was drowning in tongue. He touched me in places that I didn’t realize were sensitive and spent time doing nothing but kissing me on my neck. He invited me to his house and we eagerly made love.

Smart and sexy, Kenneth made me feel like a woman. There was only one problem: He had a girlfriend, a fact he neglected to tell me until after we had sex. The awful thing was, I didn’t really care. When he invited me to his house when his girlfriend wasn’t there, I didn’t hesitate to say yes. He never asked my age or where I lived; for the first time, it felt like I’d been able to shake my age and just be myself. I just showed up at the beach, and if the coast was clear, we would go to his place and make love. When I was with him, he paid attention to me and made sure the sex was satisfying and affectionate. He didn’t jump out of bed when we were finished to signal it was time for me to leave. We held each other and sometimes even took showers together. It was everything my first experience was not.

Kenneth opened my eyes up to what sex could be like—and the fact that an older man had educated me was not lost on me. Now that I’d been with a man, a part of me knew I was going to find it hard to be satisfied with boys my own age. Whether my assessment was accurate or not, I felt that I was now officially a part of the sexual revolution I’d been witnessing around me for the last several months. I might not have had a place in my parents’ counterculture, but at least I knew how to have sex.

He and I saw each other every so often for the next few weeks, but it was probably because I was following him around like a puppy. I am not sure he would have pursued me if I had not made myself so available to him. Not surprisingly, things between us ended without much fanfare. The time for my family’s departure was coming closer, and though I kept hinting to him about it, he never said anything. Then I stopped seeing him at his usual place. I looked around for him but was careful not to ask anyone, since I didn’t want him to be mad at me if his girlfriend found out.

When my parents told me to pack for the move, I finally gave up looking for him.

7 (#ulink_5c82d2fa-3c52-5a31-b29e-419d9c92c5b8)

THE NOTE (#ulink_5c82d2fa-3c52-5a31-b29e-419d9c92c5b8)

As our family prepared to hit the road, I decided to make the best of what was left of the summer and my remaining time with my friends. We went to the beach, shopped, and hung out on the strip whenever we could. The strip was a place where things were happening musically, but we couldn’t get into most of the clubs, so we just wandered around watching the boys watching the girls, who were watching them back.

It was all fun, but little could distract me from the reality that I was leaving this life behind. I worried incessantly about the bread truck becoming our movable house. No more bedroom, no more neighborhood, no more buying Twinkies at the liquor store or visiting the corner A&W with my friends. Any way I looked at it, there was something that didn’t feel right about this decision to leave our lives behind. My uneasiness only grew when my father showed me where all my stuff was supposed to fit in the bread truck.

“That’s all the room you get, so use it wisely,” he said.

Much like our failed attempt to drive to California in the trailer, he told us to select only our most important belongings to take with us—the rest would go to a huge yard sale. Most everything we had went into the sale, including my sewing machine, which would never fit in my storage space. One by one I put my books, most of my clothing, old magazines, and even records on the folding tables and tarps my parents set out on the front lawn. I stuffed some clothes and my favorite orange bikini into my knapsack along with some underwear and a skirt.

When we had almost emptied the room, I grabbed the brown envelope of my photographs from under the mattress and hid them at the bottom of a box of fabric and embroidery thread I was taking with me. Then my mother gave me another box to sort out. It had my Barbie and Ken dolls with the bed my father made for them.

“We won’t have room for all that,” my father said as he passed by my room. Only the essentials. I reluctantly handed these remnants of my childhood to my mother and never saw them again.

Once everything was packed, we stocked the converted bread truck with food items and extra blankets. The last things to go in were our new sleeping bags and camping gear. That purchase was to be a consolation for the loss of everything else. The next morning when we were about to say goodbye to our home, Danny caught some hippie running down the street with his new sleeping bag. Even when we’d had the entire Oracle commune living in our house, no one had ever tried to steal anything from us. It seemed an auspicious start to our adventure.

As we stared at all of our stuff packed into the back of a bread truck, the real meaning of the phrase dropping out hit home. It is easy through a contemporary lens to assume that the people who dropped out back then were thrill seekers. In spite of their questionable decisions, my parents didn’t do things just to do them. They were too serious for that. For its part, the Oracle went to great lengths to explain the spiritual rationalizations for dropping out and becoming more connected with other people, returning to some sort of a more natural state. These may sound like excuses for quitting work, but to my parents, they were much more than that. As misguided as this seems today, they believed in what they were doing, giving up their own security to pursue what they hoped would be a better life for us and for the world.

Still, my mom had her reservations. She had a crying fit the night before we left; the reality of taking us out of school and her once again stepping into the unknown was too much for her and she came close to backing out. Apparently, she wasn’t the only Oracle member with hesitations. Of the original nine families, only one other family from the Oracle did the dropout thing with us. Everyone else moved on and either got jobs or moved in with other people.

As a fourteen-year-old, I was too focused on my own experience to think about how my mother was coping. I didn’t consider that her hysteria the night before, which had led my father to give her a smack across the face, meant that she too had doubts. I didn’t consider the pressure she was under to try to hold her family together, please her husband, and still make a life for herself and her children. We were going to be living off the savings that my mother had carefully squirreled away when my father was employed. With only one other Oracle family willing to embark on this “statement of independence,” it meant they were essentially on their own. They had no real experience with this kind of living. The “turn on, tune in, drop out” lectures of Timothy Leary and his peers didn’t provide a blueprint for how you were to go on taking care of a family while living off the land.

It was early in the morning when we prepared to leave. Jan, Joan, and our friend Sarah surprised me and came to my house to say goodbye. They gave me some flowers they had picked along the road, probably from somebody’s garden. Before I got into the truck, they each hugged me and we all cried together. My mother reassured them that we would still be in the area for a while and could keep in touch, but I knew that was unlikely. We wouldn’t know where we were from one day to the next because my father was in charge. For all I knew, he would be licking his finger, holding it up to the wind to determine our next direction—his restlessness finally in the literal driver’s seat. Even though we would likely be mere miles away from Jan and Joan, something told me that the space between us would feel much larger.

My father called for me to get into the truck. I held on to my friends’ hands as I walked away until eventually it was only our fingertips touching. They each waved as we pulled out of the driveway and continued until they were completely out of my sight.

It didn’t take long for the reality of the “turn on, tune in, drop out” existence to sink in—and much as I suspected, it was not nearly as idyllic as Timothy Leary had made it sound.

That first day we got as far as the Will Rogers State Beach in Pacific Palisades on the Santa Monica Bay, not far from where we’d started. It was our first stop as “free people,” and initially my parents seemed to think we could just park there and stay as long as we liked. It turned out to be an aborted effort when, after two days, the police told us to move on. My father ranted about the establishment’s trying to own and regulate everything. He thought we should be able to land and stay anywhere we wanted in this “free country.” My mother didn’t want to fight the law, so we packed up and moved on to Zuma Beach in Malibu, which was prettier anyway. We were allowed to stay there, so we set up the camper awning and planned to relax for a little while on our own; we’d already managed to lose the other Oracle family somewhere along the coast.

But relaxing wasn’t really possible in the bread truck. We were in a cramped space, always getting in one another’s way, and my mother struggled with maintaining control. Since we’d left, my mother had been on my back about everything and kept getting on my nerves. Less than a week in, and already it was difficult to keep a converted bread truck camper clean and tidy when parking it at the beach. And with less space to move, she couldn’t distract herself with other tasks and household duties.

Shortly after we got to Zuma Beach, her frustrations boiled over, and so did mine. We got into a fight over, of all things, pancakes, and angry and frustrated with the entire situation, I stormed off to get away from the whole scene. They were the ones who’d forced us to do this. What did they think was going to happen with the five of us living in a bread truck? What did they expect? I wasn’t going to hang around if they didn’t appreciate me or were going to treat me like a little kid.

I went out to the beach where I came across a cute little curly-headed boy, about three years old, trying to swing on a swing set in a nearby playground. His parents were lying on a blanket and his mother had a sun hat covering her eyes.

“Swing me, swing me,” he said when he saw me looking over at him. I related to how ignored he must have felt, so I pushed him on the swing.

“I Stevie.” He giggled. “Swing me higher!”

I don’t know how much time had passed until his parents saw me playing with him. They invited me to sit with them and offered me a sandwich.

I found out that the father’s name was Ronald and the mother was Linda and they were living in his mother’s house while she was on her honeymoon. Ronald was a writer and Linda was a silk screen artist and they had been living in a commune before moving into his mother’s home. I gathered the mother was well-to-do and was not going to be home for a while.

I told them a bit about who I was and why I was there. Reluctant as I was about our journey, I had started to parrot my father’s philosophy because he kept the radio tuned to the Timothy Leary lectures all day. I might have been frustrated with the situation, but it was difficult to avoid the mind-set and the language of what it was all about—even if I didn’t fully understand it myself. Convincing people, and perhaps even myself a bit, that what our family was doing made sense. As it turned out, Ronald and Linda already shared our communal mind-set, so they were intrigued, and after a while, the couple and little Stevie followed me back to where my family had set up camp.

“There you are,” my mom said. She didn’t seem too concerned, just making a statement of fact. I didn’t feel all that welcome.

“This is our home,” I told Ronald and Linda.

“It’s cool, but it doesn’t seem to be very big for a family of five,” Linda commented.

“Oh, we’re managing fine,” my father interjected, always proud of his work to rid us of the trappings of the establishment. Ronald told them about where they had been living before moving to Malibu and I could see my father become more interested in what he had to say.

We spent some time with Ronald and Linda, and they started to visit us when they came to the beach. I got the feeling they were relieved to have me play with Stevie so they could enjoy some adult conversation with my parents. They had some friends living with them named Scott and Tracy, and the four adults and Stevie joined us on several nights to cook out on the beach and smoke grass.

“You guys should take advantage of the space I have at my old lady’s house,” Ronald said one night, exhaling puffs of smoke between words.

“Yeah,” Linda added as Scott and Tracy nodded their heads in agreement. Wearing a pair of loose-fitting drawstring pants, Scott was sitting on the sand while Tracy leaned with her head in his lap. We were all listening to the waves come in, and I fixated on the shadows from the campfire we’d built. The flames fascinated me and drew me in—I had to fight the urge to get too close. I was always struggling with the allure of things that could hurt me.

It didn’t take much convincing for my parents to accept Ronald and Linda’s invitation. Even though we were dropping out, there didn’t seem to be any conflict in temporarily living in a beautiful home as long as it belonged to someone else. Ronald’s mother’s house at Zuma Beach was ultramodern and spacious, located in the middle of a citrus grove overlooking the ocean.

We all settled into a rhythm at Ronald’s mom’s house. We ate what we wanted during the day and tried to be together for a communally cooked dinner. It reminded me of how things had been with the Oracle members living at our house in Santa Monica, only now we had so much more space and not as many people. It almost felt normal again. We could spread out and I even stayed in my own room.

One afternoon Stevie saw me looking at my envelope of photos and squealed, “Dat Dianne!” He looked at each one and didn’t see the secret I was holding. He didn’t notice I was nude in most of the shots. I don’t know why, but I gave him the envelope of photos. I never wanted to see them again. I had the one photo of me in the orange bikini that I kept in my backpack with a few other keepsakes—I never knew what became of the rest of the photographs.

Although they were on a type of vacation while housesitting, Ronald managed an alternative bookstore and Linda was gaining a reputation with printed fabrics. She took us to a place that carried her work. It was also a club with light shows and music that were meant to create a trippy environment, the feeling of being on LSD. Tracy and Linda were both former heroin addicts, and while they took every opportunity to lecture about the evils of heroin and how it could steal a person’s soul, no one felt that way about acid, which we discussed regularly.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: