По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

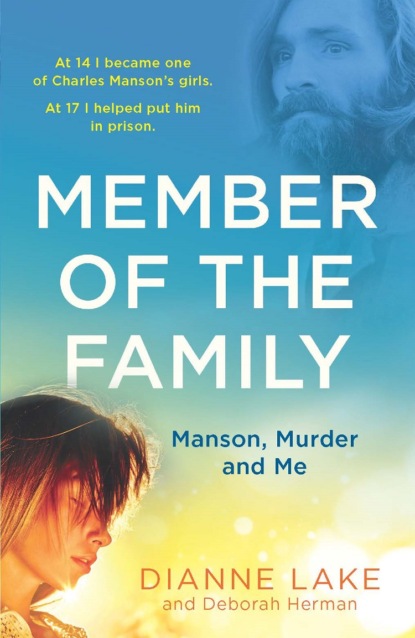

Member of the Family: Manson, Murder and Me

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I read the title aloud: “The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead.” We each looked at each other and repeated the word dead as if it held special meaning. Then we took turns reading passages to one another.

It began:

A psychedelic experience is a journey to new realms of consciousness. The scope and content of the experience is limitless, but its characteristic features are the transcendence of verbal concepts, of space-time dimensions, and of the ego or identity.

In that moment I understood why I would never be able to explain what I was feeling. There were no words.

We decided to walk around the house in our state of altered perception, stopping to look at some of my father’s paintings on the walls. His art was now reflecting the change in his interior world, and he had many of what were now being called psychedelic abstractions hanging in our house. They were very colorful and visually symbolic. We paused in front of each of the paintings and stared as the colors blended into a kaleidoscope of pattern.

When we all returned to earth, Jan and Joan went home, leaving me alone to contemplate what I’d experienced. During the acid trip, I’d seen a physical cable connecting my head to the heads of my parents, but at one point, I felt a strong sensation that this cable had been cut. In hindsight, I find it hard to say how much of this was just the acid exposing emotions that most teenagers experience as they try to separate themselves from their parents and understand who they are becoming. But in light of my parents’ behavior toward me, the experience was potent, the symbolism impossible for me to ignore. More and more, they were showing a desire for me to grow up, to consider myself an adult, to think and act independently. Whether I felt ready for that seemed irrelevant. What had started with my mother’s telling me I was too old for a good-night kiss, and continued with my parents leaving me at the love-in, had progressed to the point that both my parents were assuming I was already having sex. As much as I wanted to stay a child in an uncomplicated world, I now understood that I had to grow up.

After that first trip, my sense of self was unmistakably different. From then on, I was an individual taking a journey that was all my own, not a child lingering in the shadow of my parents. They wanted me to mature, so that’s what I would do. Though I didn’t fully understand the ramifications of that vision, some part of me was aware that things were shifting in our family and those changes seemed to be speeding up, building toward something. The sense of normality that had defined my life a few short months ago was rapidly coming undone.

6 (#ulink_efb1b331-4e07-5fce-b83a-b28c6a142d2c)

HIPPIES IN NEWSPRINT (#ulink_efb1b331-4e07-5fce-b83a-b28c6a142d2c)

The turbulence my family had been experiencing during the spring of 1967 was magnified when my parents became involved with an underground newspaper called the Oracle, run by a group of like-minded hippies.

At the time, the landscape of the counterculture was changing rapidly, and the Oracle was at the forefront of these shifts, appealing to people like my father who were already prone to questioning societal norms. Every few months it seemed that new ideas arrived and were quickly adopted by this pioneering fringe, creating a shifting cocktail of philosophy, spirituality, faith, communal ideas about property and love, and drugs that pushed the boundaries further outward. The Oracle was instrumental in preaching about much of this, drawing in my parents and others like them, and eventually shaping the beliefs that would alter all our lives.

The Southern California Oracle was the offspring of the San Francisco Oracle newspaper, which had started as a small underground rag but eventually boasted a major circulation. Here is how they described themselves in their second issue in 1967:

The incredible growth of the SF Oracle from 1200 copies to over 60000 in only six issues suggests that it meets a tremendous need for some form of spiritual communication that young people can accept. Nowhere is this need more obvious than right here in Los Angeles. It is with the blessing of the San Francisco Oracle that we now exist.

The Oracle is a newspaper, but it is more than that. It will shortly be incorporated as a religious association dedicated to sharing the insights gained from the psychedelic experience that others may ennoble their lives and place these in harmony with the forces that animate the universe. The Oracle is interested in any style of living that provides greater satisfaction, greater self-awareness, more joy, love and fulfillment. On these pages, we will explore the many roads to life enhancement, the many ways of centering one’s consciousness of releasing the joyous spirit within.

The Oracle is dedicated to making life a wondrous experience for all. In keeping with that notion, we will originate gatherings, parties, dances and other excuses for the tribes to gather and celebrate.

The paper itself was pieced together like an artistic acid trip. Each page had a different-colored font, and the artwork pushed the parameters of what would have been considered decent by the standards of the “straight world.” However, some of the writers were very serious and discussed the topic of chemically induced mystical experiences. In one issue, they did an extensive interview with Alan Watts. They took themselves seriously, and so did my father.

The paper and the people dedicated to its cause were perfect for my parents and their changing sensibilities. I don’t know if the Oracle newspaper inspired my parents’ thinking, or how much my dad had any influence on the content and artwork beyond his credit as an artist in the June 1967 edition, but those dedicated to the paper became our new community, and as a family we began to attend some of the “tribal meetings” mentioned in the paper.

The Oracle staff had an office where they put together the paper, but they also lived communally in a house in Laurel Canyon. Laurel Canyon itself was a melting pot of musical talent; hippies and artists were drawn to it as if by a gravitational pull. The house itself was described in many accounts as cavernous and was dubbed the Log Cabin, but only because it was made of wood and nestled in a forest. Any other resemblance to a cabin was greatly understating its grandeur. It was on five different levels, with a bowling alley in the basement painted in Day-Glo colors. The living room where they would hold their meetings must have been at least two thousand square feet, which was bigger than our Santa Monica home. It had fancy chandeliers and a fireplace that took up an entire wall. The thing I remember the most was the glassed-in addition, which looked like a tree house. It was more like an atrium, and during the few times I went there with my parents, there were always musicians jamming in this space. It overlooked water, and staring fixedly into the reflections of trees on the still water below, I could ignore the odd people who used the place as a crash pad.

The Log Cabin would later become the home of Frank Zappa and was legendary in the lore of Laurel Canyon and the music scene in the 1960s, but when we were there, the Oracle commune shared the space with another hippie commune led by Vito Paulekas and Carl Franzoni. They ran a free-form dance troupe and liked to refer to themselves as freaks rather than hippies. Vito was an ex-con who shared many qualities with someone else I was destined to meet, especially his almost hypnotic methods for attracting nubile young women into his sex-fueled lair. Vito was a common sight at Venice Beach, and even though he was already in his early fifties, he was considered one of the inspirations for the fashion and attitudes of the hippie movement, including his reputation for sex orgies.

I went to the Log Cabin with my parents on at least three weekends and witnessed a circus of people all doing their own thing. My parents had no problem with my seeing the goings-on of the movement regardless of whether it was technically appropriate, and now that I had taken LSD, I could tell those who were into their own trip from those who were simply hangers-on. Being older than the children, I was once again stuck in the middle, where young teens are forced to dwell; I found myself attracted to some of the men who were partying at the Log Cabin, but they hardly noticed me because they saw me as a kid.

Our house in Santa Monica also became full of life and creativity. Through these group gatherings, we became friendly with other Oraclefamilies, and several had children close in age to Kathy and Danny. It seemed like every weekend we began hosting meetings, cookouts, and picnics at our house. All of which got more interesting after my father, fresh off of studying the work of R. Buckminster Fuller, figured out how to build a geodesic dome in our backyard. One of my favorite photographs is of my brother, sister, and father and me inside the dome, with my father smoking a joint and grinning from ear to ear. People were always coming and going from our house, but after a while they stopped going. Little by little people started crashing there. I could see why. My father made things interesting and his enthusiasm gave credence and a sense of possibility to all the new ideas the group was considering.

The Oracle group had a big vision for everything from obtaining religious status to the creation of schools and employment opportunities. I know my parents had something to do with the ideas for alternative education that the Oracle was espousing. They had been very disappointed with the education I was receiving at the Santa Monica junior high. I never thought of myself as unusually bright, but I guess my education in Minneapolis had been far more advanced than what these schools were teaching us. My parents and the members of their Oracle tribe also believed children should be taught to think differently, something that was never going to happen in the public school system.

Despite their reservations with my public education, to be honest, I didn’t have a problem with school. In fact, I liked my school and my friends—both offered a structure that was becoming elusive at home. I might have been a little bored with having to study things I already knew, but it was comfortable to know where I was going and what I would be doing every day. Rules and expectations made me feel secure. Being around my parents and the free-thinking Oracle members had the opposite effect on me.

Increasingly, though, my parents weren’t listening to what I had to say about such things.

In late june, I turned the guilt trip around on my parents for leaving me at the Elysian Park Love-In. If I was old enough for them to leave me there, then I was old enough to go to the Monterey Pop Festival with my uncle, my father’s brother, who was the only relative with whom we were still speaking. Like most people, I had no idea that the concert would become a cultural touchstone and a centerpiece to the Summer of Love. I just wanted to see groups and performers like the Who, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Otis Redding. My uncle was younger than my father and a musician, and when I heard he was going to the concert, I promised that I would bring pot brownies if he’d let me come along. He agreed, and I begged my parents to let me go. I expected more of a fight from at least my mother, but they both said it would be okay—my mother even helped me bake the brownies.

When we got to the concert, we didn’t have tickets to get into the venue, but it didn’t matter. Right outside the fence was a festival of counterculture revelers that made the Elysian Park Love-In look like a family picnic. My uncle was sick with either the flu or food poisoning, so he stayed close to the truck to wait it out. He didn’t want to ruin my good time, so he pretty much told me to go on without him. The feeling around the festival was electric and I was completely free to explore. It’s difficult to recognize history when it’s happening all around you, but I knew this was something special.

I wandered around and met people, enjoying the generosity of freely shared food and marijuana and getting the freedom I’d craved to meet people who wouldn’t simply dismiss me as Clarence and Shirley’s little kid. I shared my brownies, which I hoped was not the cause of my uncle’s malady, and got myself very stoned. The festival was set for about seven thousand attendees in the arena, but there had to be over fifty thousand people on the grounds. At night, I fell asleep for a few hours in a horse barn. The horse wasn’t there, but there was a soft blanket of straw for me to crash on. There were longhairs and hippie girls sitting on the barn roof to watch the concert, which is probably how I wound up inside.

When I woke up, some people invited me to a party where I met Tiny Tim, who was tall and very funny. Or maybe everyone was funny. We were passing around joints and feeling the electricity of the music and the times. There was so much to see with the soundtrack of the music in the background—every now and then you’d perk up your ears and hear the Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, or the Grateful Dead. People were sitting together weaving yarn “eyes of God,” and others were selling handmade colorful jewelry and wind chimes. It was tactile and sensual, and wherever you looked, there was something beautiful.

Sunday was raining, but it was perfect for listening to Ravi Shankar. The strange and haunting sounds he produced on the sitar were transporting. He created a sacred atmosphere by requiring that everyone put out cigarettes if they wanted to hear him play. People complied. He encouraged them to light incense, what he referred to as joy sticks, and the sweet smell was everywhere. At the end of the performance, people threw flowers on the stage. That night brought the festival to a close with performances by the Mamas and the Papas and the Who. As I peered through the fence, I watched as Peter Townshend smashed his sunburst, maple-neck Fender Stratocaster. The crowd went wild.

I had been away for only a weekend, but when I returned my good mood quickly deflated. My home was now filled with more Oracle members who had evidently lost their lease or decided that sharing their environment with the Paulekas freak commune was no longer serving their goals. Somehow it became our responsibility to take care of these now-homeless hippies, another one of my father’s great ideas that he came up with unilaterally. As I walked through the door, I saw that our spacious living and dining rooms were both filled with transients on mattresses or in sleeping bags. Confused, I went looking for my parents.

“The Oracle had to move out of their house,” my father explained when I found him. “We told them they could crash here.”

While my mother seemed to agree with my father, I knew she wasn’t completely comfortable with the idea. I knew objecting to this would have been futile, but as was always the case, they never asked us how we would feel about our home being taken over. Adding insult to injury—there was another surprise waiting for me: My father and his friend Bob, another member of the Oracle group, had purchased bread trucks from the nearby Pioneer bakery with plans to turn them into mobile homes.

“This way if we ever want to go anywhere, we have our home with us,” my dad said.

Maybe I was missing something, but I had vivid memories of how this same scenario worked out the last time we tried living in a mobile home. When we finally did land somewhere, we were cramped and miserable. My father had the “this time will be different” look on his face so I kept my mouth shut.

The two men quickly got to work on their trucks. At first it was a matter of taking things out. Then it was a matter of putting things in. My father figured out a way to insulate the truck with soundproofing Styrofoam that I think he got from work at the telephone company. Admittedly, we all thought it was clever how he figured out how to use what was essentially trash to make a home out of a cast-off vehicle.

He worked on that truck every day for the entire summer, building a foldout table that converted into a bed as well as bunk beds that doubled as storage. My mother and I helped sew a curtain that would go completely around the truck to create privacy for anyone who might be inside. My father created a pop-up awning that extended the truck out the back to provide shade from the sun. My brother worked alongside of him soaping up screws so they could go into the metal without being stripped. Even Kathy helped sweep up the shavings from any woodwork that he did in the garage.

Despite all the work he was putting into the truck, I didn’t see the big picture at the time. Given how often he seemed to latch on to new ideas, I didn’t realize how serious this plan of his actually was. He had pretty much shut down his painting studio and had quit his job. Every bit of energy and focus was put into this truck and the apparent freedom it was going to give our family. It didn’t occur to me or anyone else that this was my father’s pattern rearing its head again.

With so much focus on the truck, it was easy to forget that our actual house didn’t seem to belong to us anymore. During that summer of 1967 the entire Oracle commune lived with us, ate with us, and slept under our roof. In general, I grew to like most of the people staying at the house—after all, it could be fun always having people around. One night a bunch of us decided to try making the legendary “mellow yellow.” Someone had been advertising it in the Oracle, and it was supposed to be made from the insides of the banana peel. They espoused it as a cheap legal high. We were typically not out of pot, but on this night, we scraped the insides of the bananas and smoked them. I didn’t feel anything, but we all laughed anyway because of how silly we felt to have fallen for the rumor.

“It’s Donovan’s fault.” I laughed when I told Jan and Joan about our experiment. We’d played Donovan’s song “Mellow Yellow” constantly, as it had been on the top of the charts in 1966 and was still going strong.

Still, some aspects of the arrangement were uncomfortable. There were people in every room, and many of them slept in the nude. From what I understood, these people weren’t used to holding back on anything they wanted to do when they wanted to do it. They were at ease with their bodies and showed no modesty at all. I felt awkward about it but didn’t say anything. Kathy walked in on a couple in the middle of having sex and started to ask a lot of questions. I doubt my parents answered them, but it did lead them to tell the couple to “cool it.” Whatever freedoms the Oracle staff enjoyed at the Log Cabin would have to be limited at least in the presence of the children.

Understandably, Jan and Joan were also apprehensive with the setup when they came over. They told me how some of the men from the Oracle kept talking to them about loosening up and asking them to come sit with them. The girls said no and laughed it off as if they had no idea what the guys had in mind. They knew what these guys wanted from them probably more than I did. Jan and Joan lived with a single mother who had taught them how to protect themselves. I wasn’t even told that I needed to protect myself or from what.

When my friends did come over, we avoided the Oracle guys and headed straight to my room. We’d talk about sex and share what we knew. Jan and Joan didn’t have much more awareness about sex than I did at this time, but we were all feeling our raging hormones and were curious. Though we wanted to experiment with boys beyond kissing, the leering eyes and suggestive comments of the Oracle members were intimidating. There really wasn’t anything romantic or sexy about the way the men from the Oracle were trying to persuade us to get close to them. It made all of us uneasy, so we started spending more time at Jan and Joan’s apartment or at the beach to dodge any situations we didn’t feel ready to handle.

Not every awkward situation could be avoided though. People would come and go from our house, which meant there were a lot of strangers around. And all of them acted friendly with one another, even if they’d just met, which made it hard to know who was trustworthy. One of the couples that moved in with us had been part of the adult film industry. Initially I didn’t think much about it, and it didn’t seem to bother anyone else. In this atmosphere of sexual freedom, no one was into making judgments.

One day this couple told me about their friend who was a photographer, saying how I would make a great subject, that with my beautiful skin and hair I should consider becoming a magazine model. The suggestion was more than flattering—in my mind I was still the girl with the squinty eyes and the fat rear end. I was vulnerable in a way ripe for exploitation, particularly since my parents’ lack of attention lowered my self-confidence.

A few days later, the photographer, an overweight guy in his mid-thirties, came to pick me up. He was wearing a button-down shirt with a suit vest that didn’t close in the front. It didn’t have any pockets, so it didn’t serve much of a purpose except to mask the sweat stains forming under his arms. He helped me select a few outfits, including the new orange bikini that I’d bought for the summer. I was finally getting breasts, so that was a positive change. I still felt fat but was hoping the rest of me would reshape itself like the women I saw in the magazines.

We drove into the woods, and he had me pose in my bathing suit on a log. He told me to imagine that I was a fairy in the forest. I thought about all the beautiful hippie girls I had seen floating through the love-ins, with flowers in their hair like wood nymphs. That is how I imagined myself, completely free and completely beautiful. Then I imagined the forest was alive and welcoming me as its fairy queen, with each leaf and plant in awe of my flowing red hair. I was no longer a freckle-faced little girl, awkward in her body. Instead I was the goddess of the forest who with one wave of my hand could bring all the flowers to life.

The reality was, we were in a remote wooded area somewhere close to my house. The photographer asked me to pose in a hundred different ways all the while clicking his shutter with each shot. I imagined myself as a redheaded not skinny Twiggy, one of the world’s most photographed models of the time. As I was lost in my imagination, he asked me to take off my top. As soon as I hesitated, he said the first words he had uttered the entire time we were there:

“There is no one here but us, and only you will see these,” he insisted. It is funny how it seemed like there was no one else in the world while he was taking my picture. He made it so I was very unaware that he was even behind the camera. I don’t know why, but I took off my top for him.

“That’s it, there is my girl,” he said as he snapped the shutter. “Now take off your bottoms. Only you will see how beautiful you are.”

At that point, I know I was caught up in the moment and the excitement of thinking that someone, even an overweight sweaty photographer, saw me as beautiful. The hippie women were not shy about their bodies, so I decided to do what he asked. I took off my bottoms and let him photograph me. I felt beautiful. I imagined myself to be the most desirable girl in the world, thinking that all the boys at the beach would want me. This would be my secret that they could see only if I let them. When we finished, I dressed and we got back into the car. When we began to drive, I realized I had no idea where we were going.