По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

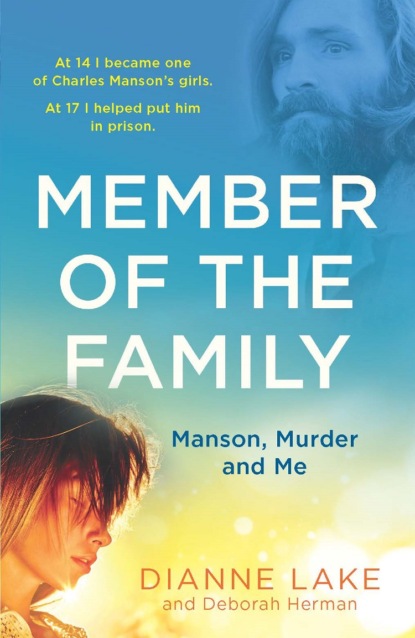

Member of the Family: Manson, Murder and Me

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“What do you mean? You read the papers. Women want to be liberated from the shackles of domesticity.”

“Yeah, right.” My mom sighed. “The women who are fighting for liberation don’t have three children to feed, clothe, and raise, and they don’t have a house to keep clean. And furthermore, when would I have any time to even read the paper, let alone contemplate my navel like that?”

“Don’t you want to be equal to men?” my father insisted.

“I am equal. But you say you are going to help me with the household chores. When is the last time you cleaned a dish or cooked a meal? What do you think would happen if I stopped doing all of these things?”

This is how their discussions went. My father would try to “liberate” my mother from domestic drudgery so she could be more passionate about the things he found interesting. Of course he wasn’t willing to make any changes to himself. While he talked a great deal about changing the order of things, when it came to his role in the family, it was just talk. Looking back, I can’t ignore the fact that they would have conversations like these while my mother was actively doing the housework while he sat and watched. He was never a participant in the household chores. Still, it never seemed to bother her. Much as she always did with him, she just shrugged it off and let him “philosophize,” as she termed it.

The fact that my father’s attitudes were changing so fast would have been amusing if it didn’t portend trouble. My father could never do anything halfway. Instead of being a casual pot smoker, he was smoking all the time, his cigarettes replaced with expertly hand-rolled joints. His eyes were always glassy and he was much more talkative unless he was being pensive. Then he could pontificate on one subject as if no one in the world could understand it with the intensity he could. He was not as excited about his work as he had been and was starting to grow out his hair. He kept it neat with Brylcreem for work, but it was beginning to appear incongruous.

As word spread of the scene happening every weekend at Griffith Park, the sea of happy hippies outgrew its environment. After the first be-in in January, there had been another one in February, a week before my fourteenth birthday, with more than five thousand people in attendance. Exciting as it was, it was like a warm-up to the main attraction. On Easter Sunday that year, March 26, 1967, the be-in moved to Elysian Park in Central Los Angeles. It provided more than six hundred acres for people to picnic, dance, groove, and embrace the counterculture.

The love-in as the “Be In” was now called, started in the very early morning and we got there with the sunrise. There were already what appeared to be thousands of people, including young families with small children and people embracing their muses. My parents set up a place to sit and listen to the music, but I didn’t want to stay in one spot. A chain of people passed by and reached out a hand to add me as a link. I turned to my parents expectantly, and they nodded and told me to meet them later back at the car. At least that is what I thought they said, and before they could change their mind, I was off.

There was too much going on for me not to explore on my own. The chain of people ran together along trails through hills, laughing and singing until we ended up somewhere on the far end of the park. We split up and I found myself in the middle of something special. The sweet smell of incense was intoxicating mixed with the pungent aroma of grass. The Doors were playing in the distance, but we were used to seeing them at these events. They weren’t famous yet; they had just released their first album in 1967. They were almost like a local band. As I walked through the path between blankets, people handed me joints and shared their bounty.

There was a circle of drummers oblivious to the music coming from other instruments just a few feet away. They were surrounded by a small tribe of men in loincloths who appeared caught up in the rapturous beats. Women were free of any confining clothing. Many were wearing muslin, and some were wrapped in blankets and not much else. There were people of every shape and size dancing together or alone as dogs wove in and out of the crowd. Little children, many golden-haired from the California sun, wore flower crowns. They were busily engaged in finger-painting on paper while their parents were decorating one another.

I was slightly buzzed, and as I wandered through the throng, a guy flashed me a peace sign as his girlfriend handed me a flower and gave me a hug. Next to them was a cute boy who had caught my eye.

“Hey, pretty,” he said. He grabbed my hand and invited me to sit with his group. They were definitely older than I was, but without my parents, I am sure I looked older than my age to them.

“Hey, you hungry?” A dark-haired girl in an Indian-print dress handed me a bunch of sunflower seeds. I eagerly accepted them and proffered money for some sodas. The boy who brought me over volunteered to get them for us, and without thinking I gave him what was left of my babysitting money. In a few minutes he returned with sodas, hot pretzels, and candy.

“Thanks, Red,” he said and squeezed in next to me.

I felt myself blush. I hadn’t realized how lonely I had been. I wasn’t seeing anyone anymore, not even the boy who got me fired from my babysitting job. I wanted someone to touch me and think I was pretty. We were now fairly stoned, and instead of getting the munchies and craving food, I fixated on wanting to be kissed. I longed to be wanted, and this boy did not disappoint. He brushed his lips softly on mine and I felt a twinge of desire. He pulled me up and we danced. I wanted to find a place behind a tree so we could explore each other’s bodies. I knew the warmth of his body next to mine would make me feel the love that everyone was talking about.

We danced and kissed and I noticed it was getting late. I told him I needed to find my parents, which probably made him aware just how young I was. I hinted that he might walk me back, but he seemed to lose interest, so I just gave him a halfhearted wave and took off.

The sun was low on the horizon. I moved through the late-afternoon shadows, dizzied and energized by the mass of people around me. Stepping over tangles of bodies and around those who were still dancing, I understood, perhaps clearly for the first time, that I was on the periphery of something—not just the spectacle in the park, but something larger than all of this. What had been going on in my house, with my parents and their friends, was happening all over California. It wasn’t just my parents, and it wasn’t just my father—it was a moment, it was in the air, and everyone in that park seemed to sense it, moving in unison to its rhythm. I didn’t understand what it was all about, but I wanted to. No one asked too many questions. They were going with the flow. And even though I was younger than the people around me, I was old enough to see the power of it all and didn’t want to be left behind.

My thoughts about the day were interrupted when I returned to where my parents had parked our car and found it wasn’t there. I retraced some of my steps to make sure I hadn’t miscalculated, but I am always careful to find landmarks in an unfamiliar place. As I realized that I was definitely where the car had been, reality set in: They had left without me. At first, I was angry that they would do that to me—it wasn’t even that late and I’d told them I would catch up with them. Quickly, though, my anger turned to fear. I had no idea how I was going to get home.

I held back tears and thought about it logically. I had just turned fourteen and didn’t want to look like a baby, but I had never been completely on my own. I had never feared the police, even though people would joke about them and call them the fuzz, so I headed right for the station, confident they could help me get home. As I was walking to the police station in the park, an older-looking boy stopped me. He must have seen that my eyes were tearing up.

“Where are you headed?” he asked. “You look lost.”

“My ride left me,” I squeaked.

“You mean your parents?” he chided.

He told me that he was in college and that he would be happy to give me a lift. He was so disarming that it didn’t occur to me until later that he might have wanted something in return. I was so upset at the fact that my parents had apparently abandoned me that I wasn’t even thinking that going with this stranger could be dangerous.

“You better wipe your eyes before you go in,” he said as he pulled the car in front of my house. He opened the door for me and handed me a handkerchief. I wiped the salt and dirt off my face, thanked him for the final time, put on my best glare, and walked inside.

When I got in, my mother burst out crying. “Dianne, I was so worried about you.”

“I told you she would find her way back home,” Clarence interjected before I got a word out.

“We needed to go and couldn’t find you,” my mother blurted out.

“She’s fine, Shirley. I told you she would be. She is resourceful,” my father said.

“I was praying that the universe would protect you and bring you home.” My mother sobbed.

All I could do was stare at her. I didn’t know how my parents’ words were supposed to affect me, but they certainly didn’t make me feel better. I grabbed a Coke and went to bed.

Their decision to leave me there was not easy to forget. It was obvious from their reactions when I returned that my mother had known leaving me was a bad idea, but she had let my father talk her into it anyway. He’d been right that I would get home safely, but that was beside the point. Like any teenager, I wanted my freedom; however, I also wanted my parents to act like parents. At heart I was conservative and shy. While I liked the colorful clothes and the music at the “happenings” I attended with my family and they were fun, I would have been just as happy staying at home and helping my mom cook and clean the house. It wasn’t my idea to become a hippie.

Ever since we’d moved to California, my father’s more impulsive instincts had been largely absent from our lives, but after the love-in, I realized they’d been just below the surface all along. I loved my father, but as had so often been the case back in Minnesota, my mother still deferred to him. Only this time it wasn’t about our house, our stuff, or a hi-fi. It was about me.

With each day, my family became more and more enmeshed in hippie culture. Our home was filled with the sounds of Buffalo Springfield, the Doors, and other new bands. In particular, the Doors were becoming more popular, so when I noticed that they would be playing in Santa Barbara, I asked my father if he would take some of my friends and me to the concert. As it turned out, no one could go with me, but my father wanted to go. It was just the two of us at a concert at the Earl Warren Showgrounds on the Saturday of the Memorial Day weekend, 1967. The lineup was the Doors, Country Joe and the Fish, Andrew Staples, Captain Speed.

It was strange being with my father by myself for the drive to the concert. I was typically never alone with him for very long. If I visited him when he was working on something he would talk to me, but we were now stuck in a car for well over an hour and a half of awkward.

I listened intently while he droned on about his new philosophies. Some of his talk seemed circular, but I liked hearing him describe his thoughts even when they confused me.

We were driving along the coast with the windows down. He had his hand with its ever-present cigarette dangling loosely out of the window while I rested my elbow on the armrest. I was humming “Light My Fire” from the new album by the Doors when my father cleared his throat.

“It’s okay for people to have sex, you know that, don’t you?”

I felt nauseated.

“If you have a boyfriend and want to have sex, it can be a beautiful thing,” he said matter-of-factly. I wanted to stop listening. I had no idea why he was telling me this. He probably figured sexual activity was inevitable in light of everything that was happening around me. “Just make sure the boy uses birth control.”

I was glad that was the gist of the discussion. This was the second time one of my parents had offered either birth control or advice about birth control. My mother had brought it up out of nowhere when I was in seventh grade. I had been going on some dates with a Jewish boy I met at the beach. I went to his house a few times and he came to mine. We did a lot of closed-mouth kissing and we talked about how much we liked each other, but that was where it ended. It never occurred to me to do anything other than kissing, and he’d never even tried.

My mother must have assumed something more was going on at the time because she asked me if I wanted to go on the pill. I was so embarrassed that I simply said no. I have no idea why my parents thought I was having sex or even wanted to. They never discussed anything with me other than birth control. I figured there must have been more to it than that, but I wasn’t about to ask.

It was hard to see it at the time, but the love-ins and rock concerts were just the start of some radical shifts in our family life. As eighth grade wound down, my parents became more enmeshed in psychedelic culture, though I didn’t realize just how much things had changed until my father gave me LSD for the first time.

It was in early June, and Jan, Joan, and I were sitting around the shortened table with my parents and a bunch of their friends. We’d just eaten a great home-cooked meal.

My father got a twinkle in his eye. “Dianne,” he said dramatically, “it is time for you to know more about who you are.” The pronouncement, especially coming from him, was mysterious, but I figured nothing could be worse than our sex discussion.

My father walked around the table passing out tabs of acid to the guests and giving smaller tabs to me, Jan, and Joan.

“Put the tab on your tongue,” he said. “I have some surprises for you.”

I was already surprised, but since my father was giving us the drugs, I didn’t hesitate to accept. He told us he would be right in the next room and that it would be best if we didn’t leave the house. He beseeched us to stay inside where he could see us if we needed his help. I had no idea what to expect, but my father’s obvious concern made the expectation exhilarating. I felt a buzz even before the drug took effect.

My father put on the new Beatles album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and at first I didn’t feel anything. Then I started to feel the music. I laughed and had to lie down. I couldn’t imagine wanting to leave the house. I had a realization of being a me that was more than me. I would never be able to put it into words, but somehow I knew in that moment that everything I would ever need was with me and inside me. When the song “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” came on, I was enthralled.

“Jan, Joan, do you see the notes?” I asked. They had to see them. They were everywhere. The notes were alive. Then I heard the calliope. It took up the entire room and filled me with ecstasy. I never heard anything so beautiful; it penetrated me from my fingertips down to my toes.

My father came into the room to check on us and handed us The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. He treated it as if it were an ancient tome. He described it as sacred writings that would give us the key to everything we ever wanted to know and ever would. I focused in on the writing on the cover. It was written by my father’s hero Timothy Leary and dedicated to the psychedelic explorer and author Aldous Huxley.