По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

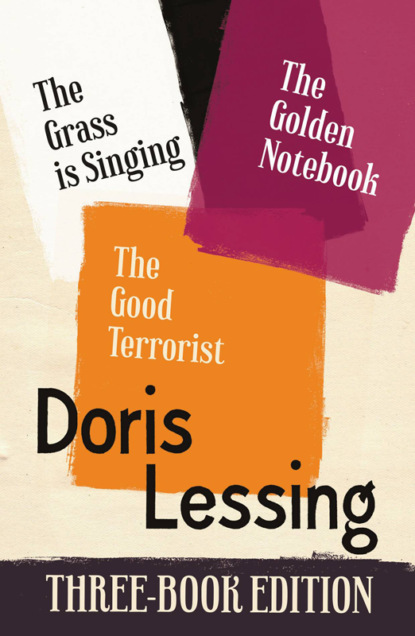

Doris Lessing Three-Book Edition: The Golden Notebook, The Grass is Singing, The Good Terrorist

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I don’t believe in treating them soft,’ she said scornfully. ‘If I had my way, I’d keep them in order with the whip.’

‘That’s all very well,’ he said irritably, ‘but where would you get the labour?’

‘Oh, they all make me sick,’ she said, shuddering.

During this time, in spite of the hard work and her hatred of the natives, all her apathy and discontent had been pushed into the background. She was too absorbed in the business of controlling the natives without showing weakness, of running the house and arranging things so that Dick would be comfortable when she was out. She was finding out, too, about every detail of the farm: how it was run and what was grown. She spent several evenings over Dick’s books when he was asleep. In the past she had taken no interest in this: it was Dick’s affair. But now she was analysing figures – which wasn’t difficult with only a couple of cash books – seeing the farm whole in her mind. She was shocked by what she found. For a little while she thought she must be mistaken; there must be more to it than this. But there was not. She surveyed what crops were grown, what animals there were, and analysed without difficulty the causes of their poverty. The illness, Dick’s enforced seclusion and her enforced activity, had brought the farm near to her and made it real. Before it had been an alien and rather distasteful affair from which she voluntarily excluded herself, and which she made no attempt to understand as a whole, thinking it more complicated than it was. She was now annoyed with herself that she had not tried to appreciate these problems before.

Now, as she followed the gang of natives up the field, she thought continually about the farm, and what should be done. Her attitude towards Dick, always contemptuous, was now bitter and angry. It was not a question of bad luck, it was simply incompetence. She had been wrong in thinking that those outbursts of wishful thinking over turkeys, pigs, etc., had been a kind of escape from the discipline of his work on the farm. He was all of a piece, everything he did showed the same traits. Everywhere she found things begun and left unfinished. Here it was a piece of land that had been half-stumped and then abandoned so that the young trees were growing up over it again; there it was a cowshed made half of brick and iron and half of bush timber and mud. The farm was a mosaic of different crops. A single fifty-acre land had held sunflowers, sunhemp, maize, monkeynuts and beans. Always he reaped twenty sacks of this and thirty sacks of that with a few pounds profit to show on each crop. There was not a single thing properly done on the whole place, nothing! Why was he incapable of seeing it? Surely he must see that he would never get any further like this?

Sun-dazed, her eyes aching with the glare, but awake to every movement of the boys, she contrived, schemed and planned, deciding to talk to Dick when he was really well, to persuade him to face clearly where he would end if he did not change his methods. It was only a couple of days before he would be well enough to take over the work: she would allow him a week to get back to normal, and then give him no peace till he followed her advice.

But on that last day something happened that she had not foreseen.

Down in the vlei, near the cowsheds, was where Dick stacked his mealiecobs each year. First sheets of tin were laid down, to protect them from white ants; then the sacks of cobs were emptied on to it, and there slowly formed a low pile of white, slippery-sheathed mealies. This was where she remained these days, to supervise the proper emptying of the sacks. The natives unloaded the dusty sacks from the waggon, holding them by the corners on their shoulders, bent double under the weight. They were like a human conveyor-belt. Two natives standing on the waggon swung the heavy sack on to the waiting bent back. The men moved steadily forward in a file, from the waggon’s side to the mealie-dump, staggering up its side on the staircase of wedged full sacks, to empty the cobs in white flying shower down the stack. The air was gritty and prickly with the tiny fragments of husk. When Mary passed her hand over her face, she could feel it rough, like fine sacking.

She stood at the foot of the heap, which rose before her in a great shining white mountain against the vivid sky, her back to the patient oxen which were standing motionless with their heads lowered, waiting till the waggon should be emptied and they free to move off on another trip. She watched the natives, thinking about the farm, and swinging the sjambok from her wrist so that it made snaky patterns in the red dust. Suddenly she noticed that one of the boys was not working. He had fallen out of line, and was standing by, breathing heavily, his face shining with sweat. She glanced down at her watch. One minute passed, then two. But still he stood, his arms folded, motionless. She waited till the hand of the watch had passed the third minute, in growing indignation that he should have the temerity to remain idle when he should know by now her rule that no one should exceed the allowed one-minute pause. Then she said, ‘Get back to work.’ He looked at her with the expression common to African labourers: a blank look, as if he hardly saw her, as if there was an obsequious surface with which he faced her and her kind, covering an invulnerable and secret hinterland. In a leisurely way he unfolded his arms and turned away. He was going to fetch himself some water from the petrol tin that stood under a bush for coolness, nearby. She said again, sharply, her voice rising: ‘I said, get back to work.’

At this he stopped still, looked at her squarely and said in his own dialect which she did not understand, ‘I want to drink.’

‘Don’t talk that gibberish to me,’ she snapped. She looked around for the bossboy who was not in sight.

The man said, in a halting ludicrous manner, ‘I…want…water.’ He spoke in English, and suddenly smiled and opened his mouth and pointed his finger down his throat. She could hear the other natives laughing a little from where they stood on the mealie-dump. Their laughter, which was good-humoured, drove her suddenly mad with anger: she thought it was aimed at her, whereas these men were only taking the opportunity to laugh at something, anything at all, in the middle of their work; one of themselves speaking bad English and sticking his finger down his throat was as good a thing to laugh at as any other.

But most white people think it is ‘cheek’ if a native speaks English. She said, breathless with anger, ‘Don’t speak English to me,’ and then stopped. This man was shrugging and smiling and turning his eyes up to heaven as if protesting that she had forbidden him to speak his own language, and then hers – so what was he to speak? That lazy insolence stung her into an inarticulate rage. She opened her mouth to storm at him, but remained speechless. And she saw in his eyes that sullen resentment, and – what put the finishing touch to it – amused contempt. Involuntarily she lifted her whip and brought it down across his face in a vicious swinging blow. She did not know what she was doing. She stood quite still, trembling; and when she saw him put his hand, dazedly, to his face, she looked down at the whip she held in stupefaction, as if the whip had swung out of its own accord, without her willing it. A thick weal pushed up along the dark skin of the cheek as she looked, and from it a drop of bright blood gathered and trickled down and off his chin, and splashed to his chest. He was a great hulk of a man, taller than any of the others, magnificently built, with nothing on but an old sack tied round his waist. As she stood there, frightened, he seemed to tower over her. On his big chest another red drop fell and trickled down to his waist. Then she saw him make a sudden movement and recoiled, terrified; she thought he was going to attack her. But he only wiped the blood off his face with a big hand that shook a little. She knew that all the natives were standing behind her stock-still, watching the scene. In a voice that sounded harsh from breathlessness, she said, ‘Now get back to work.’ For a moment the man looked at her with an expression that turned her stomach liquid with fear. Then, slowly, he turned away, picked up a sack and rejoined the conveyor-belt of natives. They all began work again quite silently. She was trembling with fright, at her own action, and because of the look she had seen in the man’s eyes.

She thought: he will complain to the police that I struck him? This did not frighten her, it made her angry. The biggest grievance of the white farmer is that he is not allowed to strike his natives, and that if he does, they may – but seldom do – complain to the police. It made her furious to think that this black animal had the right to complain against her, against the behaviour of a white woman. But it is significant that she was not afraid for herself. If this native had gone to the police station, she might have been cautioned, since it was her first offence, by a policeman who was a European, and who came on frequent tours of the district, when he made friends with the farmers, eating with them, staying the night with them, joining their social life. But he, being a contracted native, would have been sent back to this farm; and Dick was hardly likely to make life easy for a native who had complained of his wife. She had behind her the police, the courts, the jails; he, nothing but patience. Yet she was maddened by the thought he had even the right to appeal; her greatest anger was directed against the sentimentalists and theoreticians, whom she thought of as ‘They’ – the law-makers and the Civil Service – who interfered with the natural right of a white farmer to treat his labour as he pleased.

But mingled with her anger was that sensation of victory, a satisfaction that she had won in this battle of wills. She watched him stagger up the sacks, his great shoulders bowed under his load, taking a bitter pleasure in seeing him subdued thus. And nevertheless her knees were still weak: she could have sworn that he nearly attacked her in that awful moment after she struck him. But she stood there unmoving, locking her conflicting feelings tight in her chest, keeping her face composed and severe; and that afternoon she returned again, determined not to shrink at the last moment, though she dreaded the long hours of facing the silent hostility and dislike.

When night came at last, and the air declined swiftly into the sharp cold of a July night, and the natives moved off, picking up old tins they had brought to drink from, or a ragged coat, or the corpse of some rat or veld creature they had caught while working and would cook for their evening meal, and she knew her task was finished, because tomorrow Dick would be here, she felt as if she had won a battle. It was a victory over these natives, over herself and her repugnance of them, over Dick and his slow, foolish shiftlessness. She had got far more work out of these savages than he ever had. Why, he did not even know how to handle natives!

But that night, facing again the empty days that would follow, she felt tired and used-up. And the argument with Dick, that she had been planning for days, and that had seemed such a simple thing when she was down on the lands, away from him, considering the farm and what should be done with it without him, leaving him out of account, seemed now a weary heartbreaking task. For he was preparing to take up the reins again as if her sovereignty had been nothing, nothing at all. He was absorbed and preoccupied again, that evening, and not discussing his problems with her. And she felt aggrieved and insulted; for she did not care to remember that for years she had refused all his pleas for her help and that he was acting as she had trained him to act. She saw, that evening, as the old fatigue came over her and weighted her limbs, that Dick’s well-meaning blunderings would be the tool with which she would have to work. She would have to sit like a queen bee in this house and force him to do what she wanted.

The next few days she bided her time, watching his face for the returning colour and the deepening sunburn that had been washed out by the sweats of fever. When he seemed fully himself again, strong, and no longer petulant and irritable, she broached the subject of the farm.

They sat one evening under the dull lamplight, and she sketched for him, in her quick emphatic way, exactly how the farm was running, and what money he could expect in return, even if there were no failures and bad seasons. She demonstrated to him, unanswerably, that they could never expect to get out of the slough they were in, if they continued as they were: a hundred pounds more, fifty pounds less, according to the variations of weather and the prices, would be all the difference they could anticipate.

As she spoke her voice became harsh, insistent, angry. Since he did not speak, but only listened uneasily, she got out his books and supported her contentions with figures. From time to time he nodded, watching her finger moving up and down the long columns, pausing as she emphasized a point, or did rapid calculations. As she went on he said to himself that he ought not to be surprised, for he knew her capacity; had it not been for this reason that he had asked for her help?

For instance, she ran chickens on quite a big scale now, and made a few pounds every month from eggs and table birds; but all the work in connection with this seemed to be finished in a couple of hours. That regular monthly income had made all the difference to them. Nearly all day, he knew, she had nothing to do; yet other women who ran poultry on such a scale found it heavy work. Now she was analysing the farm, and the organization of crops, in a way that made him feel humble, but also provoked him to defend himself. For the moment, however, he remained silent, feeling admiration, resentment and self-pity; the admiration temporarily gaining upper hand. She was making mistakes over details, but on the whole she was quite right: every cruel thing she said was true! While she talked, pushing the roughened hair out of her eyes with her habitual impatient gesture, he felt hurt too; he recognized the justice of her remarks, he was prevented from defensiveness because of the impartiality of her voice; but at the same time the impartiality stung him and wounded him. She was looking at the farm from outside, as a machine for making money: that was how she regarded it. She was critical entirely from this angle. But she left so much out of account. She gave him no credit for the way he looked after his soil, for that hundred acres of trees. And he could not look at the farm as she did. He loved it and was part of it. He liked the slow movement of the seasons, and the complicated rhythm of the ‘little crops’ that she kept describing with contempt as usual.

When she had finished, his conflicting emotions kept him silent, searching for words. And at last he said, with that little defeated smile of his: ‘Well, and what shall we do?’ She saw that smile and hardened her heart: it was for the good of them both; and she had won! He had accepted her criticisms. She began explaining, in detail, exactly what it was they should do. She proposed they grew tobacco: people all about them were growing it and making money. Why shouldn’t they? And in everything she said, every inflection of her voice, was one implication: that they should grow tobacco, make enough money to pay their debts, and leave the farm as soon as they could.

His realization, at last, of what she was planning, stunned his responses. He said bleakly: ‘And when we have made all that money, what shall we do?’

For the first time she looked unconfident, glanced down at the table, could not meet his eyes. She had not really thought of it. She only knew that she wanted him to be a success and make money, so that they would have the power to do what they wanted, to leave the farm, to live a civilized life again. The stinting poverty in which they lived was unbearable; it was destroying them. It did not mean there was not enough to eat: it meant that every penny must be watched, new clothes forgone, amusements abandoned, holidays kept in the never-never-land of the future. A poverty that allows a tiny margin for spending, but which is shadowed always by a weight of debt that nags like a conscience, is worse than starvation itself. That was how she had come to feel. And it was bitter because it was a self-imposed poverty. Other people would not have understood Dick’s proud self-sufficiency. There were plenty of farmers in the district, in fact all over the country, who were as poor as they, but who lived as they pleased, piling up debts, hoping for some windfall in the future to rescue them. (And, in parentheses, it must be admitted that their cheerful shiftlessness was proved to be right: when the war came and the boom in tobacco, they made fortunes from one year to the next – which occurrence made the Dick Turners appear even more ridiculous than ever.) And if the Turners had decided to abandon their pride, to take an expensive holiday and to buy a new car, their creditors, used to these farmers, would have agreed. But Dick would not do this. Although Mary hated him for it, considering he was a fool, it was the only thing in him she still respected: he might be a failure and a weakling, but over this, the last citadel of his pride, he was immovable.

Which was why she did not plead with him to relax his conscience and do as other people did. Even then fortunes were being made out of tobacco. It seemed so easy. Even now, looking across the table at Dick’s weary, unhappy face, it seemed so easy. All he had to do was to make up his mind to it. And then? That was what he was asking – what was their future to be?

When she thought of that hazy, beautiful time in the future, when they could live as they pleased, she always imagined herself back in town, as she had been, with the friends she had known then, living in the Club for young women. Dick did not fit into the picture. So when he repeated his question, after her long evasive silence, during which she refused to look into his eyes, she was silenced by their inexorably different needs. She shook the hair again from her eyes, as if brushing away something she did not want to think about, and said, begging the question, ‘Well, we can’t go on like this, can we?’

And now there was another silence. She tapped on the table with the pencil, twirling it around between finger and thumb, making a regular irritating noise that caused him to tauten his muscles against it.

So now it was up to him. She had handed the whole thing over to him again and left him to do as he could – but she would not say towards what goal she wanted him to work. And he began to feel bitter and angry against her. Of course they could not go on like this: had he ever said they should? Was he not working like a nigger to free them? But then, he had got out of the habit of living in the future; this aspect of her worried him. He had trained himself to think ahead to the next season. The next season was always the boundary of his planning. Yet she had soared beyond all that and was thinking of other people, a different life – and without him: he knew it, though she did not say so. And it made him feel panicky, because it was so long now since he had been with other people that he did not need them. He enjoyed an occasional grumble with Charlie Slatter, but if he was denied that outlet, then it did not matter. And it was only when he was with other people that he felt useless, and a failure. He had lived for so many years with the working natives, planning a year ahead, that his horizons had narrowed to fit his life, and he could not imagine anything else. He certainly could not think of himself anywhere but on this farm: he knew every tree on it. This is no figure of speech: he knew the veld he lived from as the natives know it. His was not the sentimental love of the townsman. His senses had been sharpened to the noise of the wind, the song of the birds, the feel of the soil, changes in weather – but they had been dulled to everything else. Off this farm he would wither and die. He wanted to make good so that they continue living on the farm, but in comfort, and so that Mary could have the things she craved. Above all, so that they could have children. Children, for him, were an insistent need. Even now, he had not given up hope that one day…And he had never understood that she visualized a future off the farm, and with his concurrence! It made him feel lost and blank, without support for his life. He looked at her almost with horror, as an alien creature who had no right to be with him, dictating what he should do.

But he could not afford to think of her like that: he had realized, when she ran away, what her presence in his house meant to him. No; she must learn to understand his need for the farm, and when he had made good, they would have children. She must learn that his feeling of defeat was not really caused by his failure as a farmer at all: his failure was her hostility towards him as a man, their being together as they were. And when they could have children even this would be healed, and they would be happy. So he dreamed, his head on his hands, listening to that tap-tap-tap of the pencil.

But in spite of this comfortable conclusion to his meditation, his sense of defeat was overwhelming. He hated the thought of tobacco; he always had, it seemed to him an inhuman crop. His farm would have to be run in a different way; it would mean standing for hours inside buildings in steamy temperatures; it would mean getting up at nights to watch thermometers.

So he fiddled with his papers on the table, pressed his head into his hands, and rebelled miserably against his fate. But it was no good, with Mary sitting opposite him, forcing him to do as she willed. At last he looked up, smiled a twisted unhappy smile, and said, ‘Well, boss, can I think it over for a few days?’ But his voice was strained with humiliation. And when she said irritably, ‘I do wish you wouldn’t call me boss!’ he did not answer, though the silence between them said eloquently what they were afraid to say. She broke it at last by rising briskly from the table, sweeping away the books, and saying, ‘I am going to bed.’ And left him there, sitting with his thoughts.

Three days later he said quietly, his eyes averted, that he was aranging with native builders to put up two barns.

When he looked at her at last, forcing himself to face her uncontrollable triumph, he saw her eyes bright with new hope, and thought with disquiet what it would mean to her if he failed this time.

8 (#ulink_879b5fd0-9807-54df-bf9e-7b63c812a326)

Once she had exerted her will to influence him, she withdrew, and left him alone. Several times he made an attempt to draw her into his work by asking advice, suggesting she should help him with something that was troubling him, but she refused these invitations as she had always done, for three reasons. The first was calculated: if she were always with him, always demonstrating her superior ability, his defensiveness would be provoked and he would refuse, in the end, to do anything she wanted. The other two were instinctive. She still disliked the farm and its problems and shrank from becoming, as he had resigned to its little routine. And the third reason, though she was not aware of it, was the strongest. She needed to think of Dick, the man to whom she was irrevocably married, as a person on his own account, a success from his own efforts. When she saw him weak and goal-less, and pitiful, she hated him, and the hate turned in on herself. She needed a man stronger than herself, and she was trying to create one out of Dick. If he had genuinely, simply, because of the greater strength of his purpose, taken the ascendency over her, she would have loved him, and no longer hated herself for becoming tied to a failure. And this was what she was waiting for, and what prevented her, though she itched to do it, from simply ordering him to do the obvious things. Really, her withdrawal from the farm was to save what she thought was the weakest point of his pride, not realizing that she was his failure. And perhaps she was right, instinctively right: material success she would have respected and given herself to. She was right, for the wrong reasons. She would have been right if Dick had been a different kind of man. When she noticed that he was again behaving foolishly, spending money on unnecessary things, skimping expenses on essentials, she refused to let herself think about it. She could not: it meant too much, this time. And Dick, rebuffed and let down because of her withdrawal, ceased to appeal to her. He stubbornly went his own way, feeling as if she had encouraged him to swim in deep waters beyond his strength, and then left him to his own devices.

She retired to the house, to the chickens and that ceaseless struggle with her servants. Both of them knew they were facing a challenge. And she waited. For the first years she had been waiting and longing in the belief, except for short despairing intervals, that somehow things would change. Something miraculous would happen and they would win through. Then she had run away, unable to bear it, and, returning, had realized there would be no miraculous deliverance. Now, again, there was hope. But she would do nothing but wait until Dick had set things going. During those months she lived like a person with a certain period to endure in a country she disliked: not making definite plans, but taking it for granted that once transplanted to a new place, things would settle themselves. She still did not plan what would happen when Dick made this money, but she day-dreamed continually about herself working in an office, as the efficient and indispensable secretary, herself in the Club, the popular elder confidante, herself welcomed in a score of friendly houses, or ‘taken out’ by men who treated her with the comradely affection that was so simple and free from danger.

Time passed quickly, rushing upwards, as it does in those periods when the various crises that develop and ripen in each life show like hills at the end of a journey, setting a boundary to an era. As there is no limit to the amount of sleep to which the human body can be made to accustom itself, she slept hours every day, so as to hasten time, so as to swallow great gulps of it, waking always with the satisfactory knowledge that she was another few hours nearer deliverance. Indded, she was hardly awake at all, moving about what she did in a dream of hope, a hope that grew so strong as the weeks passed that she would wake in the morning with a sensation of release and excitement, as if something wonderful was going to happen that very day.

She watched the progress of the block of tobacco barns that were being built in the vlei below as she might have watched a ship constructed that would carry her from exile. Slowly they took shape; first an uneven outline of brick, like a ruin; then a divided rectangle, like hollow boxes pushed together; and then the roof went on, a new shiny tin that glinted in the sunlight and over which the heat waves swam and shimmered like glycerine. Over the ridge, out of sight, near the empty potholes of the vlei, the seedbeds were being prepared for when the rains would come and transform the eroded valley-bottom into a running stream. The months went past until October. And though this was the time of the year she dreaded, when the heat was like an enemy, she endured it quite easily, sustained by hope. She said to Dick that the heat wasn’t so bad this year, and he replied that it had never been worse, glancing at her as he spoke with concern, even distrust. He could never understand her fluctuating dependence on the weather, an emotional attitude towards it that was alien to him. Since he submitted himself to heat and cold and dryness, they were no problems to him. He was their creature, and did not fight against them as she did.

And this year she felt the growing tension in the smoke-dimmed air with excitement, waiting for the rains to fall which would start the tobacco springing in the fields. She used to ask Dick with an apparent casualness that did not deceive him, about other farmers’ crops, listening with bright-eyed anticipation to his laconic accounts of how this one had made ten thousand pounds in a good season, and that one cleared off all his debts. And when he pointed out, refusing to respect her pretence at disinterestedness, that he had only two barns built, instead of the fifteen or twenty of a big farmer, and that he could not expect to make thousands, even if the season were good, she brushed this warning aside. It was necessary for her to dream of immediate success.

The rains came – unusually enough – exactly as they should, and settled comfortably into a soaking December. The tobacco looked healthy and green and fraught – for Mary – with promise of future plenty. She used to walk round the fields with Dick just for the pleasure of looking at its sturdy abundance, and thinking of those flat green leaves transformed into a cheque of several figures.

And then the drought began. At first Dick did not worry: tobacco can stand periods of dryness once the plants have settled into the soil. But day after day the great clouds banked up, and day after day the ground grew hotter and hotter. It was past Christmas, then well into January. Dick became morose and irritable, with the strain, Mary curiously silent. Then, one afternoon, there was a slight shower that fell, perversely, on only one of the two pieces of land which held the tobacco. Again the drought began, and the weeks passed without a sign of rain. At last the clouds formed, piled up, dissolved. Mary and Dick stood on their verandah and saw the heavy veils pass along the hills. Thin curtains of rain advanced and retreated over the veld; but on their farm it did not fall, not for several days after other farmers had announced the partial salvation of their crops. One afternoon there was a warm drizzle, fat gleaming drops falling through sunlight where a brilliant rainbow arched. But it was not enough to damp the parched ground. The withered leaves of the tobacco hardly lifted. Then followed days of bright sun.

‘Well,’ said Dick, his face screwed up in chagrin, ‘it is too late in any case.’ But he was hoping that the field which had caught the first shower, might survive. By the time the rain fell as it should, most of the tobacco was ruined: there would be a little. A few mealies had come through: this year they would not cover expenses. Dick explained all this to Mary quietly, with an expression of suffering. But at the same time she saw relief written in his face. It was because he had failed through no fault of his own. It was sheer bad luck that could have happened to anyone: she could not blame him for it.

They discussed the situation one evening. He said he had applied for a fresh loan to save them from bankruptcy, and that next year he would not rely on tobacco. He would prefer to plant none; he would put in a little if she insisted. If they had another failure like this year, it would mean bankruptcy for certain.

In a last attempt Mary pleaded for another year’s trial; they could not have two bad seasons running. Even to him, ‘Jonah’ (she made herself use this name for him, with an effort at sympathetic laughter), it would be impossible to send two bad seasons, one after another. And why not, in any case, get into debt properly? Compared with some others, who owed thousands, they were not in debt at all. If they were going to fail, let them fail with a crash, in a real attempt to make good. Let them build another twelve barns, plant out all the lands they had with tobacco, risk everything on one last try. Why not? Why should he have a conscience when no one else did?

But she saw the expression on his face she had seen before, when she had pleaded they might go on holiday to restore themselves to real health. It was a look of bleak fear that chilled her. ‘I’m not getting a penny more into debt that I can help,’ he said finally. ‘Not for anyone.’ And he was obdurate; she could not move him.

And next year, what then?

If it was a good year, he said, and all the crops did well, and there was no drop in prices, and the tobacco was a success, they would recover what they had lost that year. Perhaps it would mean a bit more than that. Who knew? His luck might turn. But he was not going to risk everything on one crop again until he was out of debt. Why, he said, his face grey, if they went bankrupt the farm would be lost to them! She replied, though she knew it was what wounded him most, that she would be glad if that did happen: then they would be forced to do something vigorous to support themselves; and that the real reason for his complacency was that he knew, always, that even if they did reach the verge of bankruptcy, they could live on what they grew and their own slaughtered cattle.

The crises of individuals, like the crises of nations, are not realized until they are over. When Mary heard that terrible ‘next year’ of the struggling farmer, she felt sick; but it was not for some days that the buoyant hope she had been living on died, and she felt what was ahead. Time, through which she had been living half-consciously, her mind on the future, suddenly lengthened out in front of her. ‘Next year’ might mean anything. It might mean another failure. It would certainly mean no more than a partial recovery. The miraculous reprieve was not going to be granted. Nothing would change: nothing ever did.

Dick was surprised she showed so few signs of disappointment. He had been bracing himself to face storms of rage and tears. With the habit of long years, he easily adapted himself to the thought of ‘next year’, and began planning accordingly. Since there were no immediate indications of despair from Mary, he ceased looking for them: apparently the blow had not been as hard as he had thought it would be.

But the effects of mortal shocks only manifest themselves slowly. It was some time before she no longer felt strong waves of anticipation and hopefulness that seemed to rise from the depths of herself, out of a region of her mind that had not yet heard the news about the tobacco failure. It took a long time before her whole organism was adjusted to what she knew was the truth: that it would be years, if ever, before they got off the farm.