По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

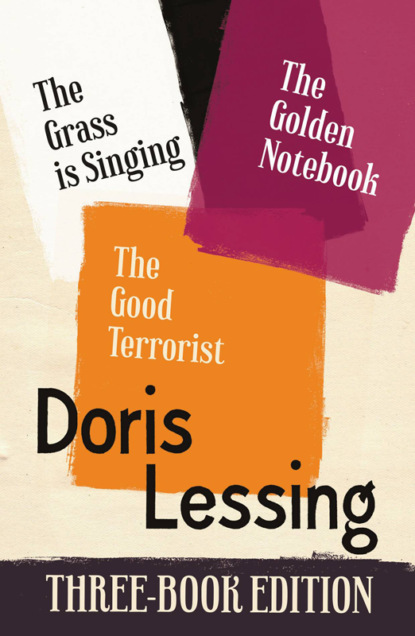

Doris Lessing Three-Book Edition: The Golden Notebook, The Grass is Singing, The Good Terrorist

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then followed a time of dull misery: not the sharp bouts of unhappiness that were what had attacked her earlier. Now she felt as if she were going soft inside at the core, as if a soft rottenness was attacking her bones.

For even day-dreams need an element of hope to give satisfaction to the dreamer. She would stop herself in the middle of one of her habitual fantasies about the old days, which she projected into her future, saying dully to herself that there would be no future. There was nothing. Nil. Emptiness.

Five years earlier she would have drugged herself by the reading of romantic novels. In towns women like her live vicariously in the lives of the film stars. Or they take up religion, preferably one of the more sensuous Eastern religions. Better educated, living in the town with access to books, she would have found Tagore perhaps, and gone into a sweet dream of words.

Instead, she thought vaguely that she must get herself something to do. Should she increase the number of her chickens? Should she take in sewing? But she felt numbed and tired, without interest. She thought that when the next cold season came and stung her into life again, she would do something. She postponed it: the farm was having the same effect on her that it had had on Dick; she was thinking in terms of the next season.

Dick, working harder than ever on the farm, realized at last that she was looking worn, with a curious puffy look about her eyes, and patches of red on her cheeks. She looked really very unhealthy. He asked her if she were feeling ill. She replied, as if only just becoming aware of it, that she was. She was suffering from bad headaches, a lassitude that might mean she was ill. She seemed to be pleased, he noted, to think that illness could be the cause.

He suggested, since he could not afford to send her for a holiday, that she might go into town and stay with some of her friends. She appeared horrified. The thought of meeting people, and most particularly those people who had known her when she was young and happy, made her feel as if she were raw all over, her nerves exposed on a shrinking surface.

Dick went back to work, shrugging his shoulders at her obstinacy, hoping that her illness would pass.

Mary was spending her days moving restlessly about the house, finding it difficult to sit still. She slept badly at nights. Food did not nauseate her, but it seemed too much trouble to eat. And all the time it was as if there were thick cottonwool in her head, and a soft dull pressure on it from outside. She did her work mechanically, attending to her chickens and the store, keeping things running out of habit. During this time she hardly ever indulged in her old fits of temper against her servant. It was as if, in the past, these sudden storms of rage had been an outlet for an unused force, and that, as the force died, they became unnecessary to her. But she still nagged: that had become a habit, and she could not speak to a native without irritation in her voice.

After a while, even her restlessness passed. She would sit for hours at a time on the shabby old sofa with the faded chintz curtains flapping above her head, as if she were in a stupor. It seemed that something had finally snapped inside of her, and she would gradually fade and sink into darkness.

But Dick thought she was better.

Until one day she came to him with a new look on her face, a desperate, driven look, that he had never seen before, and asked if they might have a child. He was glad: it was the greatest happiness he had ever known from her because she asked it, of her own accord, turning to him – so he thought. He thought she was turning to him at last, and expressing it this way. He was so glad, filled with a sharp delight, that for a moment he nearly agreed. It was what he wanted most. He still dreamed that one day, ‘when things were better’, they could have children. And then his face became dull and troubled, and he said, ‘Mary, how can we have children?’

‘Other people have them, when they are poor.’

‘But Mary, you don’t know how poor we are.’

‘Of course I know. But I can’t go on like this. I must have something. I haven’t anything to do.’

He saw she was desiring a child for her own sake, and that he still meant nothing to her, not in any real way. And he replied obdurately that she had only to look around her to see what happened to children brought up as theirs would be brought up.

‘Where?’ she asked vaguely, actually looking around the room as if these unfortunate children were visible there, in their house.

He remembered how isolated she was, how she had never become part of the life of the district. But this irritated him again. It had been years before she stirred herself to find out about the farm; after all this time she still did not know how people lived all around them – she hardly knew the names of their neighbours. ‘Have you never seen Charlie’s Dutchman?’

‘What Dutchman?’

‘His assistant. Thirteen children! On twelve pounds a month. Slatter is hard as nails with him. Thirteen children! They run round like puppies, in rags, and they live on pumpkin and mealiemeal like kaffirs. They don’t go to school…’

‘Just one child?’ persisted Mary, her voice weak and plaintive. It was a wail. She felt she needed one child to save her from herself. It had taken weeks of slow despair to bring her to this point. She hated the idea of a baby, when she thought of its helplessness, its dependence, the mess, the worry. But it would give her something to do. It was extraordinary to her that things had come to this; that it was she pleading with Dick to have a child, when she knew he longed for them, and she disliked them. But after thinking about a baby through those weeks of despair, she had come to cling to the idea. It wouldn’t be so bad. It would be company. She thought of herself, as a child, and her mother; she began to understand how her mother had clung to her, using her as a safety-valve. She identified herself with her mother, clinging to her most passionately and pityingly after all these years, understanding now something of what she had really felt and suffered. She saw herself, that barelegged, bareheaded, silent child, wandering in and out of the chicken-coop house – close to her mother, wrung simultaneously by love and pity for her, and by hatred for her father; and she imagined her own child, a small daughter, comforting her as she had comforted her mother. She did not think of this child as a small baby; that was a stage she would have to get through as quickly as posible. No, she wanted a little girl as a companion; and refused to consider that the child, after all, might be a boy.

But Dick said: ‘And what about school?’

‘What about it?’ said Mary angrily.

‘How are we going to pay school fees?’

‘There aren’t any school fees. My parents didn’t pay fees.’

‘There are boarding fees, books, train fares, clothes. Is the money going to come out of the sky?’

‘We can apply for a Government grant.’

‘No,’ said Dick, sharply, wincing. ‘Not on your life! I’ve had enough of going hat in hand into fat men’s offices, asking for money, while they sit on their fat arses and look down their noses. Charity! I won’t do it. I won’t have a child growing up knowing I can’t do anything for it. Not in this house. Not living this way.’

‘It’s all right for me to live this way, I suppose,’ said Mary grimly.

‘You should have thought of that before you married me,’ said Dick, and she blazed into fury because of his callous injustice. Or rather, she almost blazed into anger. Her face went beef-red, her eyes snapped – and then she subsided again, folding trembling hands over each other, shutting her eyes. The anger vanished: she was feeling too tired for real temper. ‘I am getting on for forty,’ she said wearily. ‘Can’t you see that very soon I won’t be able to have a child at all? Not if I go on like this.’

‘Not now,’ he said inexorably. And that was the last time a child was ever mentioned. She knew as well as he did that it was folly, really, Dick being what he was, using his pride over borrowing as a last ditch for his self-respect.

Later, when he saw she had lapsed back into that terrible apathy, he appealed again: ‘Mary, please come to the farm with me. Why not? We could do it together.’

‘I hate your farm,’ she said in a stiff, remote voice. ‘I hate it, I want nothing to do with it.’

But she did make the effort, in spite of her indifference. It was all the same to her what she did. For a few weeks she accompanied Dick everywhere he went, and tried to sustain him with her presence. And it filled her with despair more than ever. It was hopeless, hopeless. She could see so clearly what was wrong with him, and with the farm, and could do nothing to help him. He was so obstinate. He asked her for advice, looked boyishly pleased when she picked up a cushion and trailed after him off to the lands; yet, when she made suggestions his face shut into dark obstinacy, and he began defending himself.

Those weeks were terrible for Mary. That short time, she looked at everything straight, without illusions, seeing herself and Dick and their relationship to each other and to the farm, and their future, without a shadow of false hope, as honest and stark as the truth itself. And she knew she could not bear this sad clear-sightedness for long; that, too, was part of the truth. In a mood of bitter but dreamy clairvoyance she followed Dick around, and at last told herself she should give up making suggestions and trying to prod him into commonsense. It was useless.

She took to thinking with a dispassionate tenderness about Dick himself. It was a pleasure to her to put away bitterness and hate against him, and to hold him in her mind as a mother might, protectively, considering his weaknesses and their origins, for which he was not responsible. She used to take her cushion to the corner of the bush, in the shade, and sit on the ground with her skirts well tucked up, watching for ticks to crawl out of the grass, thinking about Dick. She saw him standing in the middle of the big red land, balanced among the huge clods, a spare, fly-away figure with his big flopping hat and loose clothing, and wondered how people came to be born without that streak of determination, that bit of iron, that clamped the personality together. Dick was so nice – so nice! she said to herself wearily. He was so decent; there wasn’t an ugly thing in him. And she knew, only too well, when she made herself face it (which she was able to do, in this mood of dispassionate pity) what long humiliation he had suffered on her account, as a man. Yet he had never tried to humiliate her: he lost his temper, yes, but he did not try to get his own back. He was so nice! But he was all to pieces. He lacked that thing in the centre that should hold him together. And had he always been like that? Really, she didn’t know. She knew so little about him. His parents were dead; he was an only child. He had been brought up somewhere in the suburbs of Johannesburg, and she guessed, though he had not said so, that his childhood had been less squalid than hers, though pinched and narrow. He had said angrily that his mother had had a hard time of it; and the remark made her feel kin to him, for he loved his mother and had resented his father. And when he grew up he had tried a number of jobs He had been clerk in the post office, something on the railways, had finally inspected watermeters for the municipality. Then he had decided to become a vet. He had studied for three months, discovered he could not afford it; and, on an impulse, had come to Southern Rhodesia to be a farmer, and to ‘live his own life’.

So here he was, this hopeless, decent man, standing on his ‘own’ soil, which belonged to the last grain of sand to the Government, watching his natives work, while she sat in the shade and looked at him, knowing perfectly well that he was doomed: he had never had a chance. But even then it seemed impossible to her, that such a good man should be a failure. And she would get up from the cushion, and walk across to him, determined to have one more try.

‘Look, Dick,’ she said one day, timidly, but firmly, ‘look. I have an idea. Next year, why not try to stump another hundred acres or so, and get a really big crop in, all mealies. Plant mealies on every acre you have, instead of all these little crops.’

‘And what if it is a bad season for mealies?’

She shrugged: ‘You don’t seem to be getting very far as you are.’

And then his eyes reddened, and his face set, and the two deep lines scored from cheekbones to chin deepened.

‘What more can I do than I am doing?’ he shouted at her. ‘And how can I stump a hundred acres more? The way you talk! Where am I to get the labour from? I haven’t enough labour to do what I have got to do now. I can’t afford to buy niggers at five pounds a head any longer. I have to rely on voluntary labour. And it just isn’t coming any more. It’s partly your fault. You lost me twenty of my best boys, and they’ll never come back. They are out somewhere else giving my farm a bad name, at this moment, because of your damned temper. They are just not coming to me now as they used. No, they all go into the towns where they loaf about doing nothing.’

And then, this familiar grievance carried him away, and he began to storm against the Government, which was under the influence of the nigger-lovers from England, and would not force the natives to work on the land, would not simply send out lorries and soldiers and bring them to the farmers by force. The Government never understood the difficulties of farmers! Never! And he stormed against the natives themselves, who refused to work properly, who were insolent – and so on. He talked on and on, in a hot, angry, bitter voice, the voice of the white farmer, who seems to be contending, in the Government, with a force as immovable as the skies and seasons themselves. But, in this storm of resentment, he forgot about the plans for next year. He returned to the house preoccupied and bitter, and snapped at the houseboy, who temporarily represented the genus native, which tormented him beyond all endurance.

Mary was worried by him at this time, so far as she could be worried in her numbed state. He would return with her at sundown tired and irritable, to sit in a chair smoking endlessly. By now he was a chain-smoker, though he smoked native cigarettes which were cheaper, but which gave him a perpetual cough and stained his fingers yellow to the middle joints. And he would fidget and jig about in the chair, as if his nerves simply would not relax. And then, at last, his body slackened and he lay limp, waiting for supper to come in, so that he could go to bed at last and sleep.

But the houseboy would enter and say there were farm boys waiting to see him, for permission to go visiting, or something of that kind, and Mary would see that tense look return to Dick’s face, and the explosive restlessness of his limbs. It seemed that he could not bear natives any more. And he would shout at the houseboy to get out and leave him alone and tell the farm natives to get to hell back to the compound. But in half an hour the servant would return, saying patiently, bracing himself against Dick’s irritation, that the boys were still waiting. And Dick would stub out the cigarette, immediately light another and go outside, shouting at the top of his voice.

Mary used to listen, her own nerves tense. Although this exasperation was so familiar to her, it annoyed her to see it in him. It irritated her extremely, and she would be sarcastic when he came back, and said, ‘You can have your troubles with the natives, but I am not allowed to.’

‘I tell you,’ he would say, glaring at her from hot, tormented eyes, ‘I can’t stand them much longer.’ And he would subside, shaking all over, into his chair.

But in spite of this perpetual angry undercurrent of hate, she was disconcerted when she saw him talking to his bossboy perhaps, on the lands. Why, he seemed to be growing into a native himself, she thought uneasily. He would blow his nose on his fingers into a bush, the way they did; he seemed, standing beside them, to be one of them; even his colour was not so different, for he was burned a rich brown, and he seemed to hold himself the same way. And when he laughed with them, cracking some joke to keep them good-humoured, he seemed to have gone beyond her reach into a crude horse-humour that shocked her. And what was to be the end of it, she wondered? And then an immense fatigue would grip her, and she thought dimly: ‘What does it matter, after all?’

At last she said to him that she saw no point spending all her time sitting under a tree with ticks crawling up her legs, in order to watch him. Especially when he took no notice of her.

‘But, Mary, I like you being there.’

‘Well, I’ve had enough of it.’