По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

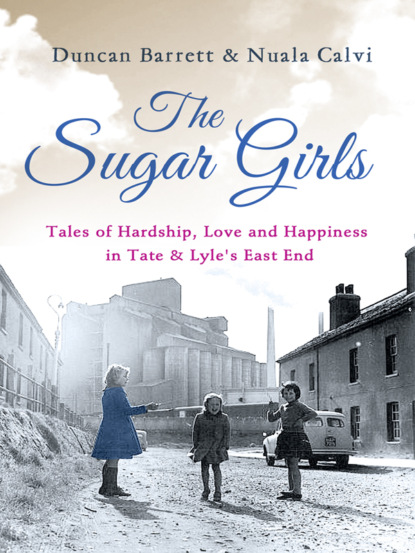

The Sugar Girls: Tales of Hardship, Love and Happiness in Tate & Lyle’s East End

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That’s it,’ Annie told her approvingly. After a while, she leaned in close and Ethel thought she was going to offer to take over the job again, but instead she whispered something in her ear.

‘Got any sweetie coupons you don’t want, darlin’?’

‘Any what?’ said Ethel, taken aback by the question.

Annie whispered more emphatically: ‘Ration coupons.’

‘No, sorry,’ Ethel replied briskly. She screwed up her face as if focusing intently on her work, and tried to avoid catching Annie’s eye.

Before long Ethel’s wrists were aching from flipping layer after layer of sugar bags, and she was beginning to wonder whether it was too soon to ask for one of her two toilet breaks.

Just then there was a sudden dimming of the lights, and a voice crackled out from the loudspeakers which were stationed around the room.

‘All personnel to shelters, please. All personnel to shelters.’

The driver of Ethel’s machine swiftly pulled a lever, and the whole mechanism ground to a halt. Carefully, Ethel laid down the bags in her hands to complete a layer, and then looked up, hoping that Annie would tell her what to do next. But Annie was gone, lost in the stream of bodies filing in an orderly but hurried fashion towards the exit.

Four years after the start of the Blitz, Tate & Lyle had got evacuations down to a fine art, and could gather 1,500 of their wartime workforce into shelters within the space of four minutes. A command centre under the can-making department received signals from the national telephone exchange, and four spotters permanently stationed on the pan-house roof provided visual confirmation. Those whose jobs meant that they couldn’t simply leave their posts – such as the men on the boilers and turbines, which were not easily shut down – were provided with blast-proof shielding to keep them safe, while the rest were immediately ordered to evacuate.

Ethel rushed to join the back of the queue of sugar girls streaming out of the door. It was only now that she heard sirens outside the factory as well.

In front of her was one of the smart girls from the office. ‘You’re new, aren’t you?’ she asked.

‘Yes, it’s my first day,’ said Ethel wryly.

‘Poor you!’ the other girl replied. ‘Well, don’t worry, the shelter’s just downstairs – we can’t have them underground because of the river. I’m Joanie, by the way. Joanie Warren.’

Ethel followed Joanie back down the black iron staircase to the second floor of the building. It was the same size as the Hesser room up above, but whatever machinery it had once housed had been removed, and blast walls had been built, dividing it into compartments. The windows were all bricked up, and wooden boards lined the floor for the workers to sit on. Ethel tried hard to suppress the feeling that she was cooped up in a dungeon.

Before long, the room was packed with bodies, mostly women and girls but a fair number of men as well. By now only a third of the refinery’s employees were male, and women who had previously been forced to leave when they got married were hurriedly being recalled by an army of door-knockers. Many had taken over jobs formerly held by men – working on the lorry bank under the Hesser Floor, manning the centrifuges and working as fitters in the can-making department. Others had been assigned a variety of unusual new roles: dehydrating vegetables to be sent out in tins to the troops (often with a hopeful note containing the name and address of the girl who had sent them) and even producing aeroplane and gun parts.

A woman pushed a steaming mug of cocoa into Ethel’s hand and offered her a Matzo cracker. ‘Could be in here a while,’ Joanie advised her, ‘so you might as well have one.’

Ethel took the Matzo and they sat huddled together, straining their ears for any sound from the skies. Eventually it came: the familiar phut … phut … phut … of a doodlebug passing overhead.

When the bombs first came to Silvertown four years earlier, Ethel was living in Charles Street, a stone’s throw from the Connaught Bridge which divided the Victoria and Albert docks. The seventh of September 1940 was a balmy summer’s day, and the Alleyne family, like the rest of their neighbours in the East End, had no idea what was in store for them.

It was Ethel’s 11th birthday, and a special tea of jelly and fruit had been planned. Louise Alleyne was busy bathing her three daughters in the tin bath – first her eldest, Dolly, then Ethel and finally little Winnie. She always took great pride in making sure they were squeaky clean and smartly turned out, with spotless white socks and gleaming ruby-red shoes. Louise had high hopes for her three girls and sometimes even made them walk around the house with books on their heads to improve their posture, just as long as the neighbours weren’t looking. A strict mother, she wasn’t averse to taking her hand to her daughters if their behaviour fell short of what was expected.

Her husband, a more laid-back character, was tinkling away contentedly on the keys of a battered old upright piano. Jim Alleyne used to say that he must have acquired his musical skill from his father, a black Saint Lucian who had married a white lady and emigrated to England. When Jim was only a few years old his parents had left him and his sister Etty with a lady he knew only as Aunty Lyle, and never returned. Aunty Lyle was white, but had married a Caribbean sailor herself, and had adapted herself to the requirements of a mixed-race household, making the best rice ’n’ peas this side of the Atlantic. Jim had become a sailor like his stepfather, but when he had children he packed it in and took a job as a greaser on the Woolwich Ferry.

Jim and his two older girls often played music together, he on the piano, Dolly on guitar and Ethel on an old accordion.

He also entertained the locals at the Graving Dock Tavern on the North Woolwich Road, and at the Tate Institute. Louise could never understand how he did it, since she herself was practically tone deaf. But that didn’t stop her being an appreciative audience.

As the sirens began to sound, Jim jumped up from his stool. ‘Louise!’ he called, ‘Get those girls dressed. We’ve got to get into the shelter.’

Louise briskly dried the girls down, and passed around a set of clean clothes from the pile she had stacked neatly by her side. Then she hurried them out into the yard, where their father stood watch by the side of the brick hut that now took up most of their outdoor space.

Louise – ever the house-proud mother – had done her best to add a touch of style to the shelter, with sheets draped down the walls to keep out the damp, a little rug on the floor offering a splash of colour, and even a double bed, which barely fitted between the four cramped walls but at least meant that no one would have to spend the night on the floor.

She and the girls had just clambered onto the squeaky mattress when they heard the faint sound of planes flying overhead, followed by a series of gentle ‘crump’ sounds in the distance. Hauling the door shut behind him, Jim caught his wife’s eye for a moment as the rumbling above them grew louder.

Before long it had turned into a roar, punctuated every few moments by deep, hollow thuds of increasing ferocity. There was a sudden whoosh overhead and Jim flung himself down on top of his wife and children, spreading him arms wide to shield them from the menace above.

The noises grew louder still, and this time the sounds were more distinct: the crumbling of bricks and masonry, the jagged tinkling of shattered glass falling from windows, and, most terrifying of all, the merciless low beat of the detonating explosives, which seemed to pound the shelter walls on all sides.

With one giant blast the brick hut shook, and lifted momentarily from the ground. Then, gradually, the storm overhead began to pass, and the noises receded into the distance.

Ethel clutched her mother and sisters close as Jim sat up on the bed and looked around him. There was a trickle of bright-red blood snaking down his brown forehead. ‘Dad,’ she shouted, ‘they got you!’

Jim put a hand up to feel for the wound, smarting as he tested the cut with his finger. He let out a laugh of relief.

‘What is it, Dad?’ Ethel asked. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Don’t worry, my darlin’,’ he replied, wiping his hand on his trousers. ‘Just caught myself on the bedhead is all.’ He leaned forward so that Ethel could see he was telling the truth. ‘I’ll be more careful next time.’

Jim hugged his wife and children to him once again, tousling Dolly’s blonde locks with one hand and squeezing Ethel close with the other, while Winnie clung on to Louise for dear life. Ethel noticed that her mother had become very quiet.

At six-thirty p.m. the all-clear was sounded and the Alleyne family emerged to see what was left of their home. Half the house had been destroyed altogether, and the half that remained was in a very bad way. Windows had been blasted out of their frames, stray tiles from the roof littered the yard, and the door had been blown off its hinges.

Carefully they picked their way through the ruined building, avoiding the scattered pieces of broken crockery that should have been serving Ethel’s birthday tea, and clambering over the remains of Jim’s beloved piano, its black and white keys strewn all over the floor.

It was only once they were on the road outside that they realised how lucky they had been. Charles Street was a scene of devastation. There were piles of rubble where some houses had once stood. Others were still standing, but gaping holes revealed the pitiful sight of their inhabitants’ ruined possessions.

A grey dust was beginning to settle all around, and Ethel coughed violently as it caught in her lungs.

Jim turned and addressed the family. ‘We can’t stay here,’ he told them. ‘We’ll head for the rest centre at Woodman Street School, and I’ll come back later and pick up some clean clothes.’

Hand in hand, the family set off on the mile-long journey, passing street after street in no better state than their own. Wardens were out with stretcher-bearers, pulling injured people out of the rubble. By the side of the road were blackened bundles, some large and some small. Ethel tried to make out what they were, but her mother pulled her close, and told her not to look.

Along the docks many warehouses were ablaze, and burning butter, sugar, molasses and oils oozed out into the water and the surrounding roads, creating boiling hot puddles, thick smoke and overpowering smells.

By the time the family arrived at the rest centre, Louise Alleyne’s head was pounding and she was beginning to feel queasy. ‘I’ve got to lie down,’ she told her husband. ‘I’m getting one of my migraines.’

Jim walked with her arm in arm until they found a quiet spot where she could have a rest. ‘You stay here for a while,’ he whispered in her ear.

The main hall of the school was thronging with anxious families, most of whom looked dishevelled and miserable. Jim took one look at the scene and bounded up to the front of the hall, where an old upright piano had been pushed to the side of the stage. ‘Excuse me, mate,’ he said to a man who was leaning on it. ‘Do you mind?’

The man seemed to shake himself out of a stupor. ‘Nah, go ahead,’ he replied. ‘Bleedin’ good idea.’

As Jim sat and began tinkling away, a crowd started to gather and a throng of young women descended on the piano. Jim was used to it – his light-brown skin and musical talent had always brought him attention from the local women, and he had learned how to handle it.

‘This is my wife’s favourite song,’ he told them. ‘I reckon she thinks it was written for her.’ He began singing Maurice Chevalier’s ‘Louise’, and the women soon joined in.

Before long, other members of the crowd were singing along as well.

That night Jim played into the small hours, just happy, like the enthusiastic crowd around him, for the opportunity to clutch at something beautiful amid all the destruction and fear. Outside, the raids had started up again. By the end of the night 250 German bombers had dropped 625 tonnes of high explosive, and more than 400 lives had been lost.