По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

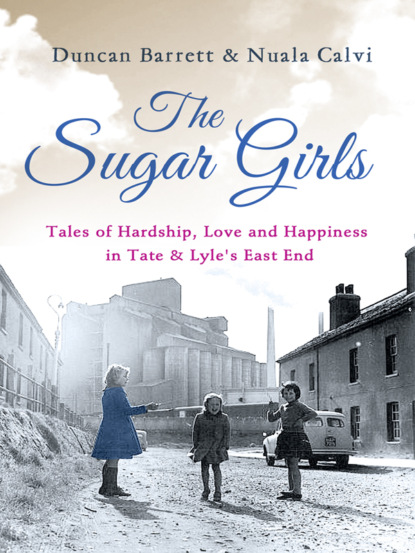

The Sugar Girls: Tales of Hardship, Love and Happiness in Tate & Lyle’s East End

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘We’ll just have to write to Harry and get you two wed,’ said her mother, hopefully. ‘It’ll all work out fine, just you see.’

If Harry had been close at hand, no doubt Edie’s father would have marched him to the altar immediately, but he was far away, fighting abroad. The agonising wait for letters to be sent and received ensued, and when the response finally came it was worse than they could have feared. Harry, it turned out, was already married.

The girls’ upstanding, Victorian father was facing the unthinkable: an unmarried daughter giving birth to a child under his roof, with no hope of being made an honest woman. The disgrace to the family was beyond measure. How would Harry Tull cope with the shame? Would he disown Edie? His wife knew she had to do something fast.

‘I’ve found out about a lovely little place run by the Salvation Army,’ she told Edie a few days later. ‘It’s in Hackney, up in North London, so no one from round here will know where you are.’

Edie nodded silently. She knew there was no point in protesting. Lilian said goodbye to her sister, and for the next few months Edie disappeared from their lives, seen only by their mother in discreet visits.

In the autumn of that year, Edie returned, looking older and more womanly than Lilian remembered. In her arms was a little baby boy. ‘I named him Brian,’ she said. ‘Brian Tull.’

Her father looked down at the sleepy face of the baby, not so unlike little Charlie who had been lost before the war, and his heart melted.

Before long Harry Tull was out in the yard once again, this time whistling away as he built a cot for Brian out of some scraps of wood. He duly proved himself the most doting grandfather in the East End.

Meanwhile his daughter Edie lived in hope that once her Harry came out of the Army he would return to her and meet the son he had fathered.

By the time Lilian joined Tate & Lyle, soon after the war was over, Reggie’s letters to her had stopped completely. Yet something about him, about the way he had made her feel when she danced in his arms, meant she just couldn’t let him go, and she felt that she never would.

Lilian kept the little black-and-white photograph he had given her when she left Kirtlington, and when she thought no one was looking she would take it out and look at it longingly. She read his last letter over and over again, trying to decipher the meaning behind the words. Had he met someone else? Had she done something wrong? The questions hanging over the end of their affair tortured her constantly.

Meanwhile her best friend, Lily Middleditch, wrote to say she had met and married a soldier while in the forces and would be moving to his home town of Blackpool. Lilian had never felt more alone.

At the factory, Lilian found she wasn’t the only one whose mind kept drifting back to the events of the war years. In her department, a girl called Winnie Taylor told of her friend Olive, who had been buried in the rubble when the shop she worked in was hit by a doodlebug. She escaped with her life but was deeply traumatised, unable to cope with any sudden noises, and thereafter always had a stammer. Many Tate & Lyle workers found it hard to escape their memories, particularly the scenes of violence and bloodshed they had witnessed. On the Hesser Floor, Anne Purcell couldn’t shake the image of a neighbour she had found lying on the ground after a bombing raid, her arteries and veins hanging out of her arm; in the Print Room, Pat Johnston was haunted by the memory of a bus conductress she saw running up her road with one eye blown out. Meanwhile, Pat’s teenage cousin was losing his hair from the stress of witnessing a woman’s head being blown off by a bomb, seconds after she had pushed him out of harm’s way.

In the factory offices, a girl called Barbara Bailey still bore the scars she had suffered when a window had blown in during a bombing raid and filled her face with glass. Her mother had told her to get under the kitchen table, but Barbara was reading a book at the time and had insisted on getting to the end of the page.

The men of the factory had their own traumatic memories to deal with. Some had been interned in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps and now struggled when they saw oriental boats on the Thames – whenever one passed the raw sugar landing, the men there shouted for ‘the bastards’ to be thrown overboard. Others had been involved in the liberation of Belsen, and told stories of the terrible scenes they had witnessed.

Many refugees had settled in the East End after the war, and among them, at Tate & Lyle, was a Polish man called Bassie. His steel-grey eyes always seemed to be staring at unknown horrors, but nobody dared ask what they were.

One bitterly cold day it was snowing, and Bassie was pulling the handle of a truck carrying bags of sugar on steel pallets. Two younger men were meant to be helping, but were slacking off and complaining about the cold.

‘You think this is cold?’ Bassie demanded suddenly.

‘Yeah, Bassie, it is,’ they replied.

‘You don’t know cold,’ he said. ‘You don’t know hard. I’ve chopped trees at 50 below zero in Siberia. When the Russians invaded our country they took us away in cattle trucks and gave us rotten fish eggs and old bones to eat. They made us dig holes to live in. If you couldn’t do it, kneel down and bang, you’re dead.’

The boys were shocked by Bassie’s words, but fascinated to hear the normally reticent man speak about his past, and were determined to question him further. They learned that he had come to Britain under an arrangement to take Polish prisoners into the forces.

‘Why didn’t you go back to Poland after the war?’ asked one of the young men, Erik Gregory.

‘I can’t go home,’ Bassie replied. ‘There is nothing there.’

‘What about your family?’ Erik asked him.

Bassie shook his head. ‘Auschwitz,’ he said quietly. ‘Gassed by the Germans. You don’t know what hardship is, and I never want you to. But don’t you take the piss with me.’

The boys nodded respectfully, and never complained to Bassie about their work again.

3

Gladys

While Lilian Tull’s family seemed to live under a curse, Gladys Taylor’s had something of a lucky streak. Although their house had received a direct hit on the first night of the Blitz, seven-year-old Gladys, her four brothers, baby sister and parents had survived – emerging blinking from their Anderson shelter just a few feet away, completely unscathed.

They had just been admitted to the local rest centre, in the basement of South Hallsville School in Canning Town, when they were intercepted by Gladys’s Aunt Jane. ‘Don’t even bother staying here, the place is packed to bursting,’ she advised them. ‘We can hitch a ride to Kent instead, and go hopping till things quieten down.’

Soon the whole family was huddled in the back of a lorry, relieved to be getting out of harm’s way. They began to curse their decision, however, when a German fighter plane swooped and began machine-gunning the vehicle as it was going over Shooter’s Hill. They passed the rest of the night cowering underneath the lorry, wishing they hadn’t listened to Aunt Jane, before finally making it safely to the hop fields in the morning. But little did they know how fortunate they had been.

While the Taylors spent the next two days hop-picking, the 600 people at South Hallsville School continued to wait for the coaches that were due to pick them up and take them to the countryside. Sunday and Monday went by, and still the vehicles hadn’t arrived. They were offered no explanations, just endless cups of tea. A rumour went round that the drivers had mixed up Canning Town with Camden Town in North London and gone to the wrong place.

As darkness fell again on Monday night, so too did the bombs. One made a direct hit on the school, demolishing half the building and causing many tons of masonry to collapse onto the people huddled below. Hundreds of terrified men, women and children lost their lives, in one of the worst civilian tragedies of the Second World War.

Five days later, when the Taylors returned to London to pick through the wreckage of their home, neighbours’ mouths gaped at the sight of them. Their names had been on the list of those declared dead, and if not for Aunt Jane they too would have ended their days in the wreckage of Hallsville.

Some attributed the Taylors’ luck to the fact that Gladys’s mother Rose was from a well-known gypsy family, the Barnards. A tiny Romany woman with long, plaited hair rolled into enormous coils on either side of her head, Rose had been expected to marry inside the gypsy community. But after a childhood spent roaming the fields of Kent and Sussex in a caravan, she had been determined to give her own children a more settled existence.

To that end she married a young man from Tidal Basin, near the Royal Victoria Dock, moving into a flat on Crown Street right next door to his parents. The neighbourhood was full of sailors who had married and settled down there – many of them black men who had taken up with local white girls, lending the road the nickname Draughtboard Alley.

Rose may have wanted a settled life, but her new husband Amos, a red-headed and rebellious seaman, had other ideas. Perhaps she should have heeded the warning lying in his parents’ garden – Amos’s uniform, helmet and gun, which had been hastily buried there when he deserted from the Army and ran off to sea during the First World War.

After fathering three sons with Rose, Amos did a second disappearing act, going AWOL from the family for 18 months without a word. When Rose could bear his silence no longer, she threw off her pinny and marched up to the shipping office, demanding that her husband be traced. The errant father was discovered to be working as a professional footballer in New Zealand, and duly returned with his tail between his legs.

The arrival on the scene of Gladys, with a shock of red hair just like her father’s, prompted the final showdown between Rose and Amos, whose seafaring could no longer be tolerated now that there were six mouths to feed. 19 Crown Street trembled to the sounds of the almighty row, which ended in his service book being ripped up and thrown onto the fire. Amos accepted his fate, and a job in the docks – where he would wistfully sing the dirty sea ditties of his youth. But he never quite forgave his daughter for thwarting his ambition.

Fourteen years later, Gladys’s own ambition in life was to become a nurse. Playing doctors and nurses had been a favourite game ever since, aged three, she had fallen ill with diphtheria and had her life saved by the staff at Sampson Street fever hospital. She had also been told more than once that, compared to other girls, she was remarkably unsqueamish, a virtue she assumed was much needed in the medical profession. Having been brought up with four brothers, she was a natural tomboy who didn’t think twice about picking up spiders or other creepy-crawlies, to the horror of the girls at school – a habit which frequently landed her in the headmaster’s office. One day she had pierced her own ears out of curiosity, and she was soon piercing those of the local gypsy boys as well. She was used to the sight of blood, thanks to her dad’s hobby of breeding chickens and rabbits to sell at the pub, which he would slaughter and nail upside down in the back yard to drain.

With no qualifications to her name, save for a half-hearted reference from her long-suffering headmaster stating that she was a trustworthy sort, Gladys headed straight to the hospital on Sampson Street as soon as school was out, and collected an application form.

She returned excitedly to Eclipse Road, clutching the papers in her hand.

‘What’ve you got there, love?’ her mother asked.

‘It’s my papers from Sampson Street. I’m going to be a nurse!’

‘Oh yeah?’ said her father, raising his red eyebrows. ‘And do you know what you have to do when you work in a hospital?’

‘Well, look after people and all that,’ said Gladys.

A mischievous grin spread across Amos’s face. ‘You have to get old men’s willies out and hold them while they wee!’

‘I’m not doing that!’ shrieked Gladys, who had never seen a grown man’s willy in her life.

‘Well you’re not going to be a nurse then, are you?’ said her father, erupting into a loud belly laugh.

Gladys tore up the papers in disgust and threw them onto the fire, watching her own ambitions fly up the chimney. ‘What am I going to do then?’ she moaned.