По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

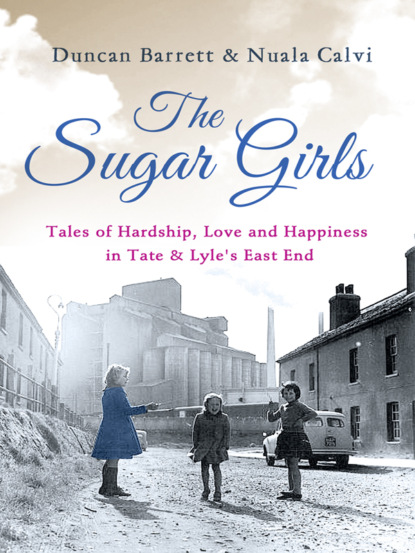

The Sugar Girls: Tales of Hardship, Love and Happiness in Tate & Lyle’s East End

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The next morning Jim kept his word, and before the rest of the family had woken up he made the journey back to their bombed-out home. Officially the road had been cordoned off, but he knew that having clean clothes for the kids would mean a lot to Louise.

When Jim arrived at 23 Charles Street and carefully made his way back inside the wrecked building, he realised that his wife was going to be disappointed. What little the bombs had spared had already been looted, and drawer after drawer fell open empty. The family would have to manage with what they had on their backs.

Before long, the Alleynes were relocated to Waunlwyd, a little village near Ebbw Vale in South Wales, where Jim had accepted a job in a munitions factory. It could scarcely have been more different from the bomb-damaged East End, and for the three girls it was an adventure in an utterly unknown world.

As the train pulled into the station Ethel leapt up from her seat. ‘Look, Dad,’ she cried, barely able to believe her eyes, ‘there are sheep and geese and donkeys just walking around in the street!’

The family lived in a little house on a hill, where Louise learned to cook on a fire instead of a stove. Ethel and Dolly went to the local school, while little Winnie stayed at home with their mother.

Dolly took to the rough-and-tumble of rural life more than Ethel, who was forever trying to get the mud off her shoes. Always the more sensible sister, Ethel was frequently mistaken for the eldest by people who met the two of them. While Dolly soon made friends with a group of local Welsh children, Ethel was not admitted into their gang, who considered her too ‘miserable and boring’.

Dolly’s favourite new pastime was playing kiss-chase with the country boys, and Ethel could never understand how her sister, who was normally such a fast runner, would keep getting caught. Ethel always ran for her life, and no one ever seemed to catch up with her.

The country life proved quite a shock to Ethel, and not just because of the farm animals. One afternoon she was walking some way behind Dolly and the other children on their way to Sunday school, when a man leaped out of the bushes and exposed himself to her. She turned on the spot and ran home at full-pelt, screaming her lungs out all the way back up the hill to the house.

‘Dad! Dad!’ she exclaimed when her anxious father opened the front door, ‘there’s a man down there with a broom handle in his trousers!’

Jim Alleyne may have been a laid-back father, but when it came to protecting his girls he was fearsome. He legged it all the way down the hill in hot pursuit of the pervert, but by the time he got there both the man and his broom handle had retreated.

By 1942, although the war raged on in Europe, for Londoners the horrors of the Blitz seemed to be behind them. Like many families, the Alleynes took the decision to return to the East End. They found a house in Oriental Road, not far from Charles Street and still in the heart of Silvertown, and Jim got a job at the Spencer Chapman chemical factory. The girls’ old school had been levelled by the Luftwaffe, so they were sent to a makeshift classroom in the local swimming pool, which until recently had served as a morgue.

Ethel was thrilled to be admitted to a gang of local kids: Archie Colquhoun, Gladys Rawlins, Johnny Jay, Alf Gosford and Lenny Bridges. After being teased by Dolly and her friends for being boring, it felt wonderful to have a group of her own to lark about with at last.

Her favourite in the new gang was Archie, a ginger-haired boy a year older than her who lived on her new road, and who was as cheeky and playful as she was serious. As they ran about the streets together, playing gobstones and knock down ginger, Ethel realised that she was smitten.

There was just one unfortunate obstacle to her future happiness: Archie preferred her sister Dolly, whose tumbling blonde curls were a far cry from Ethel’s dark, frizzy hair. When he turned up at their door one afternoon asking if ‘Blondie’ would like to go for a walk, poor Ethel was horrified.

She wasn’t one to give up easily, however, and when Archie and Dolly left the house together she followed them in secret, borrowing her grandfather’s dog from across the road as an alibi in case her stalking was discovered. She did her best to stay well back, even though she was desperate to know what they were saying to each other, and kept a beady eye out for any hand-holding or kissing.

Ethel made it as far as the Connaught Bridge before her cover was blown. ‘Ooh, she’s jealous, Archie,’ Dolly called out, loudly enough to ensure that her sister could hear her. Ethel was mortified and hurried home, dragging the unfortunate dog behind her.

She decided the best strategy was to bide her time. Dolly had no shortage of male attention and would hopefully tire of Archie’s before long. Meanwhile, Ethel made sure to remind him of her presence. At 14, Archie had already left school and was working at the Hollis Bros timber yard. Every day, Ethel was out on the front step when he walked past on his way home for dinner.

Soon enough, Archie’s interest in Dolly waned, and one day he asked Ethel if she fancied going to the pictures together at the Imperial cinema in Canning Town. She tried not to jump for joy as she accepted the invitation.

Being alone with Ethel seemed to have a sobering effect on Archie, and around her he kept his cheekiness in check, behaving like the perfect gentleman. That night he didn’t dare do more than sneak an arm around her, even in the dark of the picture house.

In fact, after several months of courting, Archie still hadn’t plucked up the courage to kiss her. One day they were walking to the park together and chatting, when one of Ethel’s friends spotted them from across the road. ‘Just do it, Arch!’ she shouted. ‘Go on!’

Archie froze like a rabbit caught in the headlights, but he knew it was now or never. While Ethel was still chatting away he suddenly turned, grabbed her and planted a great big smacker on her lips.

‘Archie!’ she chastised him, as soon as their lips unlocked, ‘I was in the middle of a sentence!’

But after that she let him kiss her whenever he liked. By the time Ethel joined Tate & Lyle, she and Archie were inseparable.

Phut … phut … phut …

Ethel and Joanie held their breath, along with the hundred or so other inhabitants of the factory shelter, as they listened to the distinctive splutter of the doodlebug. They willed the noise to continue, knowing that if the engine cut out it meant the warhead was about to fall.

The flying bombs, launched from occupied Europe, had become a regular feature of East End life ever since the D-Day landings the previous summer. But at least the doodlebugs, which flew like regular aircraft, provided enough warning to get civilians into shelters. Far more menacing were the V2 rockets, which travelled so fast – at four times the speed of sound – that the explosion was the first anybody knew of them. The shock wave alone was enough to kill unsuspecting victims far from the point of impact, and in the aftermath of a V2 strike it was not uncommon to see a normal-looking bus full of passengers, apparently sitting patiently in their seats but on closer inspection all quite dead.

At the height of the V2 menace the Royal Docks were sustaining a strike every two or three days, but Tate & Lyle’s two factories escaped a single direct hit. Plaistow Wharf had suffered its fair share of battering earlier in the war, with 54 incendiary bombs landing inside the factory, all but one of which were quickly extinguished. There was only one fatality, a Mr Kinnison who ran into an exploding bomb on his way to a shelter. Downriver, the Thames Refinery was also hit many times, but only two minor casualties were reported.

Various rumours had sprung up to explain the firm’s apparent lucky streak. At the Thames Refinery, the most popular theory was that their iconic chimney – the tallest in the area – provided such a good landmark for the docks that the Luftwaffe were reluctant to damage it. At Plaistow Wharf, the story went that the mysterious Hesser company had begged Hitler not to damage their precious packing machines.

Fortunately for Ethel, Tate & Lyle’s good luck continued to hold out, and the splutter of the doodlebug finally began to recede into the distance. The inhabitants of the shelter were able to relax, and Ethel let out a sigh of relief.

Moments later the all-clear siren began to sound, and the men and women around her were suddenly getting to their feet.

‘Back to work then,’ Joanie said cheerfully, munching on the last of her cracker and brushing a few stray crumbs from her lap onto the floor. Ethel followed as they made their way back up the black iron stairs.

On the Hesser Floor, Joanie retreated up to the office, while Ethel returned to her machine, determined to perfect her packing technique. But a friendship had already been forged. Before they left work that day, the two young women had arranged to go to the pictures together.

To begin with, the rigours of her new job took their toll on Ethel. At the end of each day her hair was grey with sugar dust and her clothes were stiff with it. Every night her wrists ached painfully from the twisting movement that she had to repeat over and over again packing hundreds of sugar bags. At work, when it got really bad, she would be sent to the factory surgery, where a nurse would rub ointment on her wrists and bandage them up temporarily, before sending her straight back to the Hesser Floor. But as time went on her muscles grew accustomed to the exertions, and she found herself growing stronger and more robust.

While the work of a sugar girl was building up the muscles in Ethel’s body, her mind soon got some exercise as well. The packers had to tally up the number of sugar bags that had been packed each day and display the result on a board at the base of each machine. Ethel had always been good at maths in school and had no problem with this, but she noticed that a girl on the next machine was struggling. Before long she was doing the other girl’s tally as well as her own.

Her efforts did not go unnoticed up in the office, where the forelady Ivy Batchelor stood gazing out through the glass window over her Hesser girls. Soon she had invited Ethel up to the office to try her out on a new job, calculating the overall tonnage of the entire department. Ethel was delighted, especially since it meant working with Joanie and the other office girls. She hadn’t made any friends on the factory floor and spent most lunchtimes eating a sandwich in the cloakroom on her own while the others all went to the canteen.

Louise Alleyne could not have been more proud of her daughter’s promotion, especially since Gladys Rawlins, from Ethel’s group of friends at home, had now also joined Tate & Lyle and was not progressing beyond sweeping the floor. When Ethel informed her mother of her friend’s dead-end job, she responded in no uncertain terms, ‘They put you on a broom, you come straight home. No girl of mine’s going to sweep floors for the rest of her life.’

The words stuck in Ethel’s mind, making her all the more determined to distinguish herself at work and win her mother’s approval.

As the war moved into its final months, trips to the factory shelters grew increasingly rare. At eight p.m. on 8 May 1945 the voice of company telephonist Nellie Franks was heard over the loudspeaker system announcing that Victory in Europe had been declared. Production was shutting down immediately, and it was time to down tools and begin the party.

Most of the workers congregated in the Recreation Room, where the celebrations were soon underway, carrying on until well after midnight. Outside the factory gates, the locals had lit a huge bonfire made from railway palings and were dancing around it. Even the refinery director, Oliver Lyle, was spotted enjoying a quick jig with them on his way home.

Few parts of the country had as much reason to celebrate the end of the war as the East End, and the area lived up to its reputation for enjoying a good knees-up. Flags and bunting from the King’s coronation nine years earlier were scavenged from old cupboards and strung up all over the houses, effigies of Hitler and his generals hung from the lamp-posts, and more bonfires sprung up in the war-damaged streets, those same East Enders who had fought the blazes caused by the Luftwaffe now raiding telephone kiosks for directories to keep the fires burning. Some enthusiastic souls let off fireworks they had been storing for six years, although the explosions, however beautiful, weren’t universally popular among the battle-weary population.

While some grateful Christians hastened to church as soon as they heard the news, the majority of people hit the local pubs, where the sawdust was trampled underfoot more furiously than ever before. The amount of alcohol consumed was prodigious, and before long the drunkenness had spread to every street. Any pianos that had survived the bombing were dragged outside, along with accordions and radiograms, to provide the soundtrack to a party on a scale never seen before, and the locals sang and danced into the early hours of the morning.

Ethel and Archie headed to a pub in North Woolwich. Unfortunately, even on such a joyous occasion, not everyone was intent on celebrating the peace. As they got onto the bus, Archie accidentally brushed past a drunk man, who took offence and tried to lunge at him.

The man hadn’t counted on Archie’s lady friend, however. Ethel may have been thin, but she was wiry, and before the man could get to her beloved Archie she had clouted him round the ear.

The nervous 14-year-old who had stood outside the gates of the factory had gone. Ethel was a sugar girl now.

2

Lilian

When Lilian Tull came to Tate & Lyle shortly after the end of the war, she was older than most new arrivals. A lanky, fair-haired woman of 23, she worked in the can-making department, where the Golden Syrup tins were assembled. Lilian had arrived on the job with a heavy heart, and her colleagues noticed a sad, far-away look in her eyes. At break times she could often be seen gazing at a small photograph that she kept in the pocket of her dungarees.

Lilian’s job was to check that the bottoms of the syrup tins were properly sealed. She would pick up five at a time using a long fork and then suction test each one on a special disc. The ones that were faulty fell off and were sent for resealing, while the others continued on their way to the syrup-filling department.

The can-making suited Lilian, because the machines were so noisy it was difficult to talk. Many of the girls had developed the ability to lip-read, but even so the forelady, Rosie Hale, kept an eye out for anyone who seemed to be neglecting their machines, patrolling the room on a balcony above the girls and shouting ‘No talking! Back to work!’ She never had need to scold Lilian, who lacked the high spirits of her chirpy colleagues.

From her earliest years life had been a struggle for Lilian, and she knew the bitter taste of poverty well, having grown up in the dark days of the Great Depression. The Tull family had all slept in a single room on the ground floor of 19 Conway Street, Plaistow. The children shared a bed with their parents, which became increasingly crowded since their mother Edith seemed always to be pregnant or nursing a newborn. Nine babies came along altogether, and were kept quiet with dummies made from rags stuffed with bread and dipped in Tate & Lyle sugar.