По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

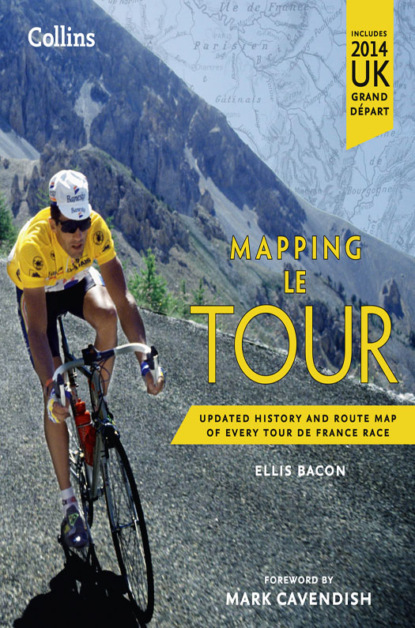

Mapping Le Tour: The unofficial history of all 100 Tour de France races

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At last – a clockwise Tour, for the first time since 1912. While the riders could ‘unwind’ after two decades of dizziness caused by following what had become a very samey anti-clockwise route around the edge of France, the watching public, too, must have appreciated the change of direction.

The dizzy heights of the race’s mountain climbs continued to capture the imagination as well, and 1933 was the first year that the organisers introduced an official grand prix de la montagne – the climber’s prize that would later use that garish white and red polka-dot jersey to identify the leader in the competition. That wouldn’t come until 1975.

Vicente Trueba – ‘The Torrelavega Flea’, hailing from the same Cantabrian town as Óscar Freire, who won Spain’s first, and only, green jersey in 2008 – hoovered up the big points available on most of the climbs in both the Alps and then the Pyrenees, including topping the Galibier and the Lautaret on stage 7, the Peyresourde and the Aspin on stage 17, and the Tourmalet and the Aubisque on stage 18, all at the head of the race.

Over in the French camp, both defending champion André Leducq and 1931 winner Antonin Magne were back, helping to make up a very strong team, but it was another member of the squad, 26-year-old Georges Speicher, who came to life in the Alps, winning two stages, and then won a third en route to Marseille to take the yellow jersey, which his team ably helped him defend all the way to Paris.

The race literally had a new direction, the French were still winning, and the race was more popular than ever, continuing to help shift copies of L’Auto, as had been the intention since the outset way back in 1903.

Spaniard Vicente Trueba conquered the Alps and Pyrenees, becoming the first rider to claim the grand prix de la montagne crown

1934 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

28th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

“I thought my Tour was over. But then, suddenly, on one of the corners further down the descent, I spied Vietto making his way back up to me – in order to give me his bicycle.”

1934 winner Antonin Magne was grateful for the help he received from French national team-mate René Vietto

This purple patch of home Tour winners like André Leducq, Antonin Magne and Georges Speicher was all well and good, but what the French public really loved – and still love – is a rider up against it, selfless and emotional.

With former fans’ favourite, the hapless Eugène Christophe, having retired in 1926, 20-year-old René Vietto fitted the bill perfectly to become France’s new chouchou. Riding in the service of defending champions Speicher, Leducq and Magne, Vietto found himself having to help Magne, in particular. On the descent of the Col de Puymorens, on stage 15, Magne damaged his front wheel, and so Vietto stopped and gave him his. Having been in the front group, and perhaps overcome with the frustration of being left behind, Vietto wept at the side of the road while waiting for a new wheel. Pretty endearing. The next day, while descending the Portet d’Aspet, it was deja-vu: this time it was Magne’s rear wheel and Vietto was in Magne’s group again. It was some time before he realised there was a problem. Once he did, he rode back up the hill to give Magne his bike so that his French team-mate could continue – and win the Tour de France.

Those tears shed by Vietto would have dried soon enough, though: not only did Vietto come away with four stage victories, but he also won the second edition of the race’s official mountains competition, out-climbing inaugural winner Vicente Trueba. He won French hearts, too.

In all, the French won twenty stages out of twenty-four, which in 1934 included the Tour’s first ever individual time trial as part of the Tour’s first ever ‘split stage’: stage 21a in the morning – an 81-km (50-mile) road race between La Rochelle and La-Roche-sur-Yon; and stage 21b that afternoon – the 90-km (56-mile) time trial from La-Roche-sur-Yon to Nantes.

For the first time, too, the Tour’s average speed crept above the 30 kph (18.6 mph) mark.

An altruistic René Vietto (left) aids compatriot Antonin Magne on the Col de Puymorens

1935 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

29th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

Romain Maes became the fifth rider – and still the last – to have led the race from the first stage all the way to the finish in Paris. The Belgian escaped the clutches of the peloton on the opening stage, and while he at first appeared to present no real danger to overall contenders such as defending champion Antonin Magne, when Maes slipped through a railway crossing in Haubourdin on the outskirts of Lille just before the gates closed, with a group of chasers hot on his heels, the rest of the race was stopped in its tracks and he was able to hold on to win by a minute.

Maes battled gamely on through the first week in the maillot jaune, even finishing the stage 5b time trial between Geneva and Évian in fourth place, while Magne fought hard to steadily close the gap.

However, when Magne was hit by a car in the race convoy on the Col du Télégraphe on stage 7, and had to abandon the race, Maes found himself with a 12-minute lead over the rest. That same stage was also marked by the death of Spain’s Francisco Cepeda, who died from his injuries after a crash on the descent of the Col du Galibier.

The race route had taken another step towards resembling modern Tour routes, with shorter stages than ever – interspersed, nevertheless, with a few longer ones too – and three individual time trials, following the success of the race’s first one in 1934, as well as three team time trials. It was also at the 1935 Tour that the famous ‘red kite’, strung over the road to mark each stage’s final kilometre, made its first appearance.

Maes finished things off as fabulously as he’d started them: just as he had on the first stage, he escaped the clutches of the main bunch on the final stage, bursting into the Parc des Princes alone in a blur of yellow to win overall by almost 18 minutes.

Romain Maes storms to victory in the Parc des Princes velodrome having led the race from start to finish

1936 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

30th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

If a return to five stages run as team time trials and no individual time trials at all made the 1936 Tour feel like a step back in time, it was but a temporary blip. There was to be a return to what resembles the modern Tour, complete with individual time trials, in 1937, and with it a new era as Henri Desgrange, the founding father and race organiser since the first edition in 1903, stepped aside to let Jacques Goddet, Desgrange’s deputy at L’Auto, take hold of the reins.

However, having had a prostate operation prior to the 1936 race, and already struggling on stage 1, Desgrange had to abandon his own race, handing over what he hoped was only temporary control of his event to Goddet as early as stage 2.

Defending Tour champion Romain Maes then abandoned on stage 7 –the by-now regular ‘queen stage’, which included the brutal climbs of the Télégraphe, the Galibier and the Lautaret – and it was his Belgian team-mate, Sylvère Maes, and no relation, who rose to the top in the Alps.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: