По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

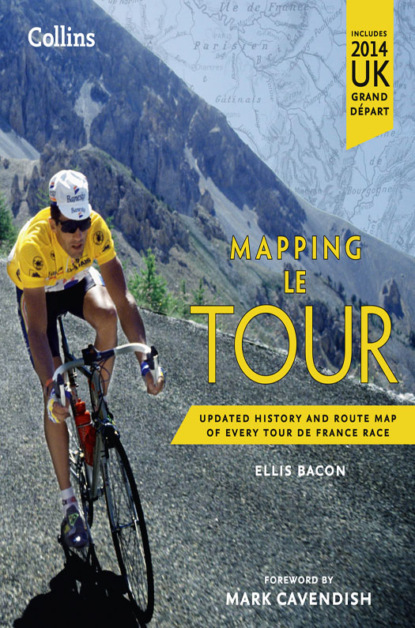

Mapping Le Tour: The unofficial history of all 100 Tour de France races

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Frenchman Louis Trousselier was the first rider to win the Tour de France on points

1906 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

4th Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

The 1906 edition of the Tour was a true tour of France, increased to thirteen stages from eleven, and reaching further afield than ever before: up to Lille in the north, Nice in the southeast, Bayonne in the furthest southwest corner, close to the Spanish border, and Brest, in Brittany, to the northwest.

It was also the first time that a stage started in a different town to the finish the previous day, when Douai hosted the start of stage 2, some 40 km (25 miles) from the Lille finish of stage 1.

It was a real Tour of ‘firsts’: for the first time, too, the race ventured outside French territory, when the stage from Douai dipped into German-held Alsace-Lorraine, and the city of Metz (today inside the French border), on its way to Nancy.

When it came to the competition, René Pottier, the man who had stunned the cycling world the previous year by managing to ride up the supposedly unridable Ballon d’Alsace, did it again, making it first to the top of the same climb when it featured on stage 3, and this time holding his advantage all the way to the finish in Dijon.

Having already won stage 2, and by taking another four stage wins en route to Paris, including the tough fifth stage over the Côte de Laffrey and the Col Bayard, Pottier beat the always-consistent Georges Passerieu – a Frenchman who finished in the top ten in every stage, including winning two stages – on points, 31 to 39. It was the rider with the fewest points who won, stage winners being awarded one point, two points being awarded for second place, etc., and was a system race organiser Henri Desgrange was to retain until the 1913 Tour, which reverted to being contested on time.

Pottier, it seemed, had an illustrious career ahead of him, having proved himself at the Tour as the sport’s best climber.

René Pottier was unbeatable in the mountains

1907 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

5th Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

The 1907 Tour started on a sombre note as the 1906 champion, gifted 27-year-old climber René Pottier, had committed suicide in January.

The fifth edition’s opening stage followed the route of the famous cobbled Classic, Paris-Roubaix, which had run since 1896, and although 1906 Tour runner-up – and now race favourite – Georges Passerieu had won the 1907 edition of the one-day race, it was 1905 Tour champ Louis Trousselier who took the victory in Roubaix in July.

The race followed a very similar route around the edge of France to that of 1906, again taking in the city of Metz, then still in Germany, and adding a second foreign sojourn by briefly drifting onto Swiss soil on stage 4 from Belfort to Lyon. The total number of stages ramped up to fourteen, and the race included its highest mountain pass yet by adding the 1326–m (4350–ft) Col de Porte, in the Chartreuse mountains of southeast France, to the route of stage 5 from Lyon to Grenoble.

There was a South American flavour added to the mix, too, in that Lucien Petit-Breton – a Frenchman born in Brittany who had moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina, as a child with his family, only returning to France in 1902 to enlist in the French army – was a very real contender for overall victory, having finished fifth overall at the 1905 Tour and fourth in 1906. Winning the very first edition of the Italian one-day Classic, Milan-San Remo, earlier in the 1907 season hadn’t done his prospects much harm, either.

Petit-Breton – real name Lucien Mazan – had adopted the pseudonym while bike racing in Argentina, a moniker presumably given to him by Buenos Aires locals, to hide the fact that he raced from is disapproving father.

After taking control of the race on stage 10 to Bordeaux, the little Breton held on to the lead the rest of the way to the finish in Paris.

Overall winner Lucien Petit-Breton leads the stage between Toulouse and Bayonne

The Tour takes on the Ballon d’Alsace, in the Vosges mountains of eastern France, in 1908. The Ballon, the first ever genuine mountain climb in the Tour, first featured in the 1905 race, five years before the first appearance of the Pyrenees, and six years before the Alps.

1908 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

6th Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

“It’s time to hand over the mantle. Next year’s Tour is for Faber.”

1908 Tour champion Lucien Petit-Breton following his second consecutive overall victory, suggesting that Luxembourg’s François Faber, his Peugeot team-mate, is the rightful heir to the Tour crown

Lucien Petit-Breton arrived at the 1908 edition of the Tour in rude form, having already won that year’s Paris-Brussels – a one-day race still in existence, now held in September, but then held in April.

The 1908 Tour followed the exact route of the previous edition, both starting on Paris’s Ile de la Jatte and finishing at the Parc des Princes. The only real change was the number of starters – up to 114 from 93 the year before – and Petit-Breton’s absolute dominance of the race this time, becoming the first rider to win two Tours (winner of the inaugural Tour, Maurice Garin, having been disqualified after cheating to win the 1904 edition).

Although London-born Georges Passerieu – second at the 1906 Tour to the late René Pottier – put up a good fight, winning stages 1, 5 and 13, and standing out as the only rider capable of getting over the Col de Porte and ‘Pottier’s mountain’, the Ballon d’Alsace, without walking, his Peugeot-Wolber ‘team-mates’ (riders often simply shared the same sponsors rather than necessarily working as a team), Petit-Breton and François Faber, dominated the race with five and four stage victories apiece, respectively.

René Pottier’s younger brother, André, helped to keep the family name alive by leading the race over the Col Bayard and Côte de Laffrey, but simply wasn’t in the same league as his more famous sibling, and could only finish seventeenth overall in Paris.

François Faber struggles over the summit of the Ballon d’Alsace

1909 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

7th Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

True to his word, 1907 and 1908 winner Lucien Petit-Breton retired from racing and followed the 1909 Tour as a journalist, leaving the door open for his former team-mate, François Faber, to take the race.

At 6 ft 2 in and weighing 91 kg, ‘The Giant of Colombes’ must have taken advantage of his bulk to help keep him warm in a race run in freezing conditions, and thought to still be the coldest weather ever encountered by the Tour.

Faber, to all extents and purposes a Frenchman but officially a Luxembourger, blazed to six stage wins – five of them consecutive – on his way to becoming 1909 Tour champion, and the race’s first non-French winner.

Mondialisation – globalisation – is an oft-bandied-around term in modern Tour de France circles to describe the ever-growing number of countries that the race has visited and the ever-increasing number of nationalities that have taken part as riders. But the 1909 Tour saw not only its first foreign winner in Faber, but after Belgium’s Cyrille van Hauwaert won the opening stage, non-French riders and French riders shared the fourteen stages with seven wins apiece.

The 1909 race had again followed a very similar route to that used in both 1907 and 1908, but the Tour was about to become much more mountainous…

François Faber won six stages on his way to overall victory in 1909

France’s Octave Lapize trudges up the Col du Tourmalet in 1910. It was the first time that the 2115-m (6939-ft) pass had been used at the Tour, and was in fact the first time that the Pyrenees had been used at all. Despite having to walk, he was the first rider across the summit, and on the next climb — the Col d’Aubisque — he accused the race organisers of being murderers for taking the race over such difficult terrain. Lapize nevertheless went on to win the 1910 Tour overall.

1910 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

8th Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

“Crossed the Tourmalet. Very good road. Perfectly passable. Steines.”

Alphonse Steines’ telegram to boss Henri Desgrange having failed to cross the Col du Tourmalet in January 1910

Although the overall race distance changed little, with only one extra stage added to make fifteen at the 1910 edition of the Tour, the big change was the addition of Pyrenean climbs to the race.

The Portet d’Aspet, Col du Peyresourde, Col d’Aspin, Col du Tourmalet and Col d’Aubisque all featured for the first time.

It was one of Henri Desgrange’s employees, Alphonse Steines, whose job it had been to map the race since its 1903 beginnings, and it was therefore Steines that Desgrange sent to scout out the Pyrenees in January 1910 in the hope of including some tougher climbs that summer.

Steines almost killed himself trying to cross an impassable, blocked-by-snow Tourmalet but, for reasons only known to himself – perhaps not wishing to upset Desgrange – he sent his boss a telegram to say that the 2115-m (6939-ft) climb was “perfectly passable”.

Come July, the snow had indeed gone, but 18 km of riding and walking up gradients of up to 10 per cent on unmade roads would test even the Tour’s best riders in 1910.

Reaching the top of the Tourmalet without stopping – an easily quantifiable feat of strength in those early days of the Tour’s climbs – earned Gustave Garrigou a 100-franc prize for his no-doubt considerable trouble.

He wasn’t even first over the Tourmalet, though; that honour fell to overall race winner Octave Lapize, who then crested the summit of the stage’s next climb, the 1709-m (5606-ft)-high Col d’Aubisque hollow-eyed and spitting, “You’re all murderers!” in the race organisation’s general direction.

1910 also saw the first appearance of the voiture balai – the broomwagon – so called because it’s the final vehicle in the race convoy, ‘sweeping up’ riders unable to go any further due to exhaustion or injury. With the Pyrenees making their first appearance in the race, there were plenty of riders who needed it.