По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

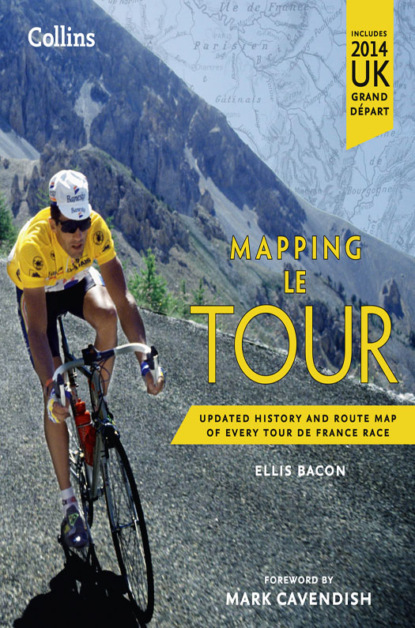

Mapping Le Tour: The unofficial history of all 100 Tour de France races

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Following the war, 1913 and 1914 Tour champ Philippe Thys had arrived at the 1919 race out of shape and in ill health, quitting on the first stage. He arrived at the 1920 Tour in June a changed man, and proceeded to dish out a hammering to his rivals, taking the yellow jersey on stage 2 and never relinquishing it, with the added bonus of no fewer than four stage victories along the way.

In Paris, Henri Desgrange’s face must have been a picture as three Belgians stood atop his podium in the Parc des Princes.

That made it three Tour victories for Thys – the ‘winningest’ rider in the race’s history so far. The poor performances of the French riders – Honoré Barthélémy was the best placed of them down in eighth – angered Desgrange, who took out his fury on Henri Pélissier, who in turn had quit the race in a huff. Even golden-boy Eugène Christophe couldn’t help Desgrange out with any fan-friendly heroics: the unlucky Frenchman’s forks may have stayed in one piece on this occasion, but his body didn’t, and he was forced to retire on the seventh stage with backache.

It had arguably been an easier Tour than many of the previous editions, with only five mountain stages against the usual six or seven, and the flatter stages seemed to play into the hands of the Belgians. Despite that, and despite Desgrange’s desire to see ‘his’ French riders in the thick of the action, the following two Tours followed much the same format.

Invading crowds celebrate with riders as they finish in the Parc des Princes velodrome

1921 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

15th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

A still-sulking Henri Pélissier didn’t even turn up to the 1921 Tour, while Tour organiser Henri Desgrange – with whom Pélissier had fallen out – continued to earn a reputation as somewhat of a curmudgeon, with his on-a-whim rules, his constant complaints about riders not trying hard enough and his anger at France’s apparent inability to challenge the dominant Belgian riders.

He might have been secretly pleased when 1920 Tour winner Philippe Thys was forced to quit the race after the first stage, suffering from illness, perhaps secretly hoping that it would open the door for France’s best hope of overall victory, Honoré Barthélémy.

The Belgians, however, found themselves with strength in numbers, and it was 33-year-old Belgian rider Léon Scieur – who had only learned to ride a bike aged 22 – who came to the fore.

The man who had taught him to ride was none other than 1919 Tour winner Firmin Lambot, who hailed from the same Belgian village – Florennes – as Scieur. In fact, the pair remain the only two riders to come from the same town who have both won the Tour de France.

Barthélémy helped save French blushes by taking third spot overall, albeit more than two hours adrift, but with Scieur’s compatriot Hector Heusghem again finishing runner-up, as he had done the year before. The Belgians had more than just arrived; they had positively taken over the Tour de France.

The scars of the First World War are still evident as riders make their way through ruins in Montdidier

1922 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

16th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

Just as it had done since 1913, the Tour continued to follow the same tried and trusted anti-clockwise route from Paris to Le Havre on stage 1, down France’s west coast, through the Pyrenees, then the Alps, with a final stage from Dunkirk back to Paris. The drudgery seemed to be amplified by yet another Belgian win – the seventh in succession – this time a second win by 1919 champion Firmin Lambot, now a relic of a man at 36 years, 4 months and 9 days old. He remains the oldest ever winner of the race.

Stage 4, between Brest and Les Sables-d’Olonne, saw some older names come to the fore as Philippe Thys – Tour champ in 1913, 1914 and 1920 – took the stage victory, and perennial nearly-man Eugène Christophe took hold of the yellow jersey.

However, on the Galibier, on stage 11, Christophe – having by then dropped out of overall contention by losing too much time on stage 9 – experienced the misfortune of his forks breaking for a third time at the Tour. Yellow jerseys and stage wins had made him a household name, but luck – or a lack of it – would see to it that he was destined never to win his beloved Tour de France.

While Alpine giants the Col d’Izoard and Col de Vars both made their first Tour appearances – on stage 10 between Nice and Briançon – crowd favourite the Col du Tourmalet, which had appeared in the race every year since 1910, had to be dropped from the route of stage 6 due to snow.

Firmin Lambot and Joseph Muller quench their thirst between Les Sables-d’Olonne and Bayonne

1923 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

17th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

If the previous few editions of the race had become dull and somewhat predictable, national pride was restored when Henri Pélissier became the first French winner since Gustave Garrigou in 1911.

Pélissier’s victory came despite organiser Henri Desgrange having opined a couple of years earlier that Pélissier “will never win”, threatening he would never put him on the front of his newspaper, L’Auto, in retaliation for what he viewed as Pélissier’s laziness as a rider.

Pélissier set Desgrange straight all right in 1923, forcing the Tour organiser to print a L’Auto cover that went against his earlier wishes as Pélissier crushed his closest rivals by more than half-an-hour overall.

Along the way, runner-up Ottavio Bottecchia became the first Italian to wear the yellow jersey after sprinting to victory on stage 2 from Le Havre to Cherbourg, and proceeded to ride a consistent race, while Pélissier took a beating from compatriot and two-time runner-up Jean Alavoine in the Pyrenees. However, Alavoine crashed on stage 10 and was forced to retire the next day, while Bottecchia was outclassed in the Alps by Pélissier.

In a combination of what Desgrange had done with his race in the past – first basing it on overall time, then on points, and then back to cumulative time – for the first time in 1923, a two-minute time bonus to the winner of each stage was introduced. It was a practice that was to fall in and out of favour over the years.

Pélissier clashed again with Desgrange at the 1924 Tour and, following his retirement from cycling in 1927, Pélissier’s life took a turn for the worse. After his wife committed suicide in 1933, he was shot and killed in 1935 by his mistress, who had acted in self-defence.

Ottavio Bottecchia became the first Italian to don the iconic maillot jaune

1924 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

18th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

“One of these days he’s going to make us put lead weights in our pockets because he thinks that God made man too light.”

1923 Tour champion Henri Pélissier after quitting the 1924 Tour in disgust at what for him were Henri Desgrange’s constant efforts to make the race even harder

With the life of the winner of the 1923 Tour, Henri Pélissier, ending in tragedy, what an ill-fated time it was in the Tour’s history, when 1924 and 1925 champion Ottavio Bottecchia was also found dead in mysterious circumstances years later.

Bottecchia was found unconscious at the side of the road in June 1927, close to his home near Udine, in northern Italy, seemingly having crashed on his bike. He had a fractured skull and never regained consciousness, dying twelve days later. Officially, his death was attributed to injuries sustained from the crash. The conspiracy theory, however, is that he was murdered by Mussolini-supporting fascists for voicing his low opinion of the Italian prime minister.

Bottecchia won the first stage of the 1924 Tour – a stage that had become the regular opener, between Paris and Le Havre – and then held on to his lead along each side of ‘the hexagon’, over fifteen stages, and back to Paris. Bottecchia had become the first Italian to finish on the podium the year before, and stepped up to take cycling’s ultimate prize. So pleased was he with his yellow jersey, in fact, that he wore it all the way home to Milan on the train.

With no French rider even on the podium in 1924 – yet another argument between the two Henris, Desgrange and Pélissier, saw the defending champion quit the race early on – this early mondialisation of the Tour came at France’s expense. Things were really going to change in 1925 – bar Bottecchia winning again.

Ottavio Bottecchia climbs through the crowds on the Col du Tourmalet

1925 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

19th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

While Ottavio Bottecchia again won the Tour de France in 1925, fundamental changes were made by organiser Henri Desgrange to help push his race forward. The Tour increased its number of stages – up to eighteen from the fifteen it had been run over for so long – and the time bonuses for stage wins were done away with, for the time being. Desgrange even went as far as proposing that every rider was to eat the same amount of food, but that idea was dropped after the riders threatened to strike.

The race also started a little further outside Paris, in the suburb of Le Vésinet, while new stage start/finish towns included Mulhouse, near the Swiss border and, a little further south, spa town Évian.

Bottecchia started where he had left off, winning the first stage to Le Havre before losing the jersey two days later to unheralded Belgian Adelin Benoît. There was to be no repeat of the Italian’s 1923 Tour win when he wore the famous golden tunic from start to finish, but Bottecchia was back in yellow after winning the flat stage 7 between Bordeaux and Bayonne.

Benoît then showed the race his climbing legs, winning the tough first day in the Pyrenees and reclaiming the race lead before Bottecchia took control once more the next day – and this time retained yellow all the way to Paris.

It was also Eugène Christophe’s last Tour – the unlucky Frenchman whose dreams of winning the race were dashed by broken forks, but who nonetheless would always be remembered as the first ever wearer of the yellow jersey in 1919. Christophe finished a lowly eighteenth overall, almost seven hours down on the Italian winner. In fact, no French rider was even to finish in the top ten; Romain Bellenger was the highest-placed home rider in eleventh.

A weary Bartolomeo Aimo struggles up to the Col d’Izoard

1926 (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

20th Edition (#ulink_243e008e-0037-5637-ab0b-dc7c054278e7)

Radical changes the year previously turned yet more radical as the Tour started outside Paris for the first time. Évian, a town that had featured in the race for the first time only the year before – and best known today for its bottled water – was truly put on the map thanks to being used for the race’s Grand Départ. The race returned to its Paris start in 1927, however, where it remained until 1951, and a start in Metz. Only then did the race start in a different town or city each year, until 2003 when, for one year only, it started again in Paris, on the site of the Au Réveil Matin café, where it had started in 1903, to celebrate 100 years of the race. In a sad footnote, the building was gutted by fire in late 2003, barely two months after the Tour start.

At 5745 km (3570 miles), the 1926 edition was, and remains, the longest-ever Tour de France, although Desgrange dropped the total number of stages down to seventeen from eighteen the year before. He preferred longer, more epic stages, and judged the distances of the 1925 stages to be too short.