По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

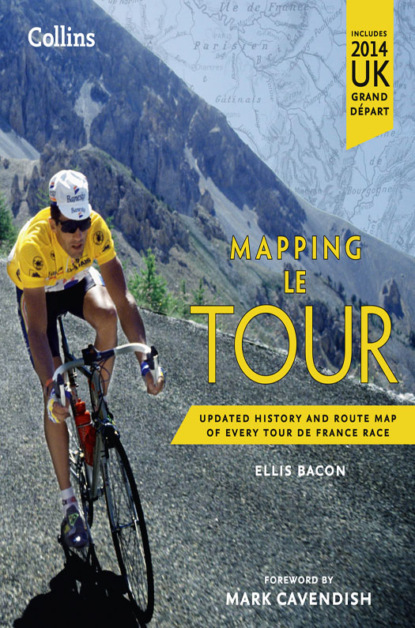

Mapping Le Tour: The unofficial history of all 100 Tour de France races

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

After hours slumped on a metal crowd barrier at the finish of the stage in Boulogne-sur-Mer, waiting for the race to arrive, our trip was rounded off nicely by watching Erik Zabel show Romans Vainsteins a clean pair of heels to take the bunch sprint.

I’d enjoyed following the Tour as a fan and, just two years later in 2003, I would follow it for the first time as a journalist.

Since then, I’ve returned year after year, which strangely means that I haven’t really noticed the race’s rather swift evolution from French holiday to English-speaking-dominated sports event. That dominance looks set to continue, but the race remains fiercely French in its goal of showcasing the country’s stunning countryside and terrain.

Each October, the unveiling of the following year’s route in Paris is eagerly awaited by the world’s press, and by the Tour’s millions of fans at home. Once that familiar hexagonal shape of France with the race route laid out across it is beamed around the world, people begin to plan their holidays around it. The riders, meanwhile, get straight to work, scouting out the roads – and the climbs in particular – named on the following year’s itinerary. It is that hard work and attention to detail, across the winter and in the early part of the season, that marks out the true contenders from the also-rans come the summer.

The Tour has also gone beyond the confines of France, and over the years has enjoyed sojourns to Belgium, Italy, Spain and Switzerland, as well as seeking out new roads further afield, in the Netherlands, Ireland and Britain. The Pyrenees made their first appearance in 1910, while the Alps followed in 1911. It also makes regular visits to the Massif Central, and the Vosges mountains in eastern France, where the riders have tackled the Puy de Dôme and the Ballon d’Alsace, respectively.

Host cities such as Paris, Lyon, Marseille and Bordeaux have appeared regularly on the route since the Tour’s first edition in 1903, and as cities in countries other than France were added, so, too, grew the breadth of contenders. As well as ever-increasing numbers of riders from neighbouring countries like Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Italy and Spain, ‘international milestones’ include the first participation by an African rider, Tunisian Ali Neffati, at the 1913 Tour, and the first riders from Australia – Snowy Munro and Don Kirkham – a year later in 1914. In 1937 came the first British riders – Bill Burl and Charles Holland – although neither finished; it wasn’t until 1955 that Brian Robinson and Tony Hoar became the first Brits to complete the Tour. Greg LeMond became the first American stage winner in 1985 and, after the Colombia-Varta team’s appearance at the Tour in 1983, Victor Hugo Peña becoming the first Colombian to wear the yellow jersey, albeit for only three days, in 2003.

Today, the Tour organisation is faced with the task of ensuring that the enduring image of riders toiling up fan-filled mountain sides and streaming past sunflower-filled fields does indeed endure … To paraphrase Tour boss Christian Prudhomme’s message, which he is at pains to get across: the Tour exists to allow people to dream.

The scenery and routes used allow people in far-flung corners of the world to see France in a justly flattering light: laid bare in all its glory for the riders to fight against and the spectators – both roadside and televisual – to appreciate. It is an event that has made national and international heroes of previously local heroes, and has brought life to corners of France, and the globe, that needed it…

Long may it continue.

How to use this book (#ulink_7d8f5b0b-0c65-5d5c-9dbd-5dd2a1efd54f)

The Route (#ulink_2a55d9a9-bfe5-57b8-9b5a-9f5f287363b9)

The Climbs

“I had one of the hardest moments ever on the Col du Glandon in 1977. I was at the end of my career, and what I had was gone by then.”

Eddy Merckx

Top 10 highest climbs

Many battles have been won and lost over the Tour’s mountain stages. Whether it is in the Alps, Pyrenees or the Massif Central, riders need grit, determintaion and extraordinary fitness to overcome the punishing ascents of these now famous climbs.

The Winners

Tour wins by country

Riders make their way from Lyon to Marseille during stage 2 of the first Tour de France. Only twenty-one competitors would complete the race, covering 2428 km (1509 miles) in six days.

1903 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

1st Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

“The ideal Tour would be one that only one rider was capable of finishing.”

Henri Desgrange, founder of the Tour de France

Just six stages made up the route of the first Tour de France in 1903. Rather than the race being easy by today’s standards, however, the shortest stage – between Toulouse and Bordeaux – was still 268 km (167 miles), while most of the rest were well over 400 km (250 miles).

Where the stages were easier compared to today’s, however, was in their relative lack of climbing, with a route that avoided both the Alps and the Pyrenees, instead focusing on featuring France’s major towns and cities.

While the Ballon d’Alsace, in the Vosges, is widely credited with being the first major climb to have been included on the Tour route, in 1905, the inaugural race did in fact include a number of climbs, although they were not noted as particular challenges to the riders.

Stage 1, between Montgeron, on the southeast edge of Paris, and Lyon featured both the Col des Echarmeaux and the Col du Pin-Bouchain – 712 m (2336 ft) and 759 m (2490 ft) high, respectively – while on the second stage riders had to tackle the Col de la République, near St-Étienne, with France’s Hippolyte Aucouturier the first rider to reach the top of the 1161-m (3809-ft)-high pass.

Named as one of the pre-race favourites, Aucouturier, riding as an ‘independent’, had failed to finish the Tour’s opening stage due to stomach cramps, but was allowed to start stage 2 under rules that said that he could no longer remain in the hunt for the overall prize. He went on to win the second stage in Marseille, and repeated the feat on stage 3.

The first Tour ended in front of an enthusiastic crowd at the Parc des Princes velodrome, where another pre-race favourite, Frenchman Maurice Garin, riding in the colours of bicycle manufacturer La Française, took his third stage win of the race, and with it the honour of being the first Tour de France winner, having held the lead since his victory on the opening stage in Lyon.

The Tour was born, but its second edition was to be a lot less celebrated.

Maurice Garin (in white) becomes the Tour’s first champion

1904 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

2nd Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

“The Tour de France is over, although its second edition will have been, I fear, its last – a victim of its own success.”

Henri Desgrange, founder of the Tour de France, following the 1904 race

It’s become somewhat of a cliché, but the second edition of the Tour de France, in 1904, was almost its last.

Geographically, the 1904 Tour followed the same route as the first edition the previous year, again starting in Paris and taking in the major cities of Lyon, Marseille, Toulouse, Bordeaux and Nantes, before finishing once more in the Parc des Princes, Paris.

However, the race was marred by interventions from a by-now feverish public, while following the race it was discovered that the first four in the overall classification, including defending champion Maurice Garin, had cheated, and were disqualified from the race, handing victory to 19-year-old Henri Cornet, who remains the race’s youngest-ever winner.

On the race’s second, hilliest stage, between Lyon and Marseille, local Lyon lad Antoine Fauré led the race over the Col de la Rébublique while behind him the race favourites, including Garin and his brother, César, were set upon by masked men, believed to be Fauré’s supporters.

That year was also the first recorded instance of tacks being thrown onto the road by partisan crowds – something that would happen intermittently throughout the Tour’s history, including as recently as the 2012 Tour when the race passed over the Mur de Péguère on stage 14.

It took some time for the organisers of the 1904 Tour to wade through all the accusations and rumours at the end of the race, but in November they came to the decision to ban the two Garin brothers – who had finished first and third – with the older Maurice having apparently illegally been given food by one of the race organisers themselves, as well as allegedly having covered part of the route by train.

Runner-up Lucien Pothier was handed a lifetime ban by French governing body the Union Vélocipédique Française (although he was later permitted to start the Tour again, in 1907), while fourth-placed Hippolyte Aucouturier, again one of the race favourites, having failed to finish the first stage of the 1903 race due to illness, was one of those believed to have cheated by gripping a cork in his mouth that was attached to a string tied to the back of a car.

Spectators use tacks and pebbles to sabotage the stage between Nantes and Paris

1905 (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

3rd Edition (#ulink_8745b11a-9614-5f47-b142-89979717aa44)

Despite the race having tackled the Col de la République in its previous two editions, the third Tour de France entered new territory in 1905 by introducing its first serious, leg-crunching, lung-busting climb in the shape of the Ballon d’Alsace. It was also made up of shorter stages, albeit with an increase in their number – up to eleven from six.

After his despair at the previous year’s mass cheating, race director Henri Desgrange almost cancelled the 1905 Tour as early as its first stage, during which tacks were again thrown onto the road. All the riders punctured apart from 1904 runner-up Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq, though eventual overall race winner, Louis Trousselier, was nevertheless able to recover and win stage 1 from Paris to Nancy.

For stage 2, between Nancy and Besançon, it was out with the Col de la République and in with the Ballon d’Alsace, in the Vosges mountains. Wrongly, the Ballon d’Alsace is considered the Tour’s first major climb, but it was recognised as such by the race organisers more for its steepness than its height: at 1178 m (3865 ft), it is just 17 m (56 ft) higher than the Col de la République. Indeed, the Col Bayard, climbed later, on stage 4 of the 1905 Tour, stands at 1246 m (4088 ft).

With an average grade of 6.9 per cent, climbed from the north from the town of St-Maurice-sur-Moselle, Desgrange predicted that none of his race’s participants would be able to ride over the Ballon d’Alsace. René Pottier, however, had other ideas, stomping on the pedals to become the first rider to the top of the climb, although he was overtaken later in the stage by Hippolyte Aucouturier.

Overall race winner Trousselier – victorious thanks to five stage wins and Desgrange’s newly introduced points, rather than time, system of determining the winner – was a deserving Tour champion, but gambled his winnings away in a single, celebratory evening after the finish in Paris.