По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

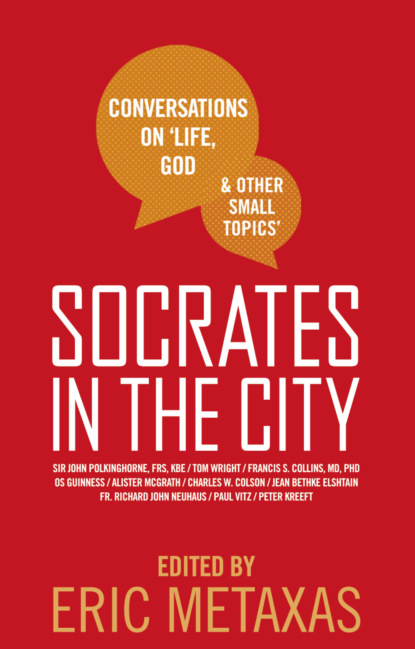

Socrates in the City: Conversations on Life, God and Other Small Topics

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

If you would do this, while I’m talking— certainly not while Dr. Polkinghorne is talking— but if you would, before the evening is over, put down your name and address, even if you have done this before, because we’re starting a new database, and I know that we’ve lost a few of you. Put down your name and address, SAT scores. . . .

Socrates in the City, for those of you who are new to these events, is designed to help busy New Yorkers take a moment out of our busy lives to stop and think a bit more deeply about what life is all about— to answer the big questions or to try, at least, to begin to answer them. Socrates famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” I think many of us could probably do with a bit more self-examination. I know I could, and having speakers like Dr. Polkinghorne is meant to make that process a bit easier for us.

Of course, these events are only the tip of the iceberg. We would like to think that these events, these evenings, would kick off the Socratic process in each of us and that in between these events, you might read one or more of these books that are available on the book table. I recommend them very highly to you. We’re selling them at no profit to us. They’re wonderful books, and they’re wonderful to give away to your particularly unthoughtful friends. Of course, Dr. Polkinghorne will happily autograph his books, and I will autograph any of the other books that you would like to have autographed.

By the way, I should say that tonight’s event is generously being sponsored by the New Canaan Society, a group I had a very small hand in founding almost nine years ago. The New Canaan Society is a men’s fellowship that has, as its modest goal, the idea of helping its members be better husbands and fathers. We have dinner events in New York about once a month, among other things, and if you would like more information, we’ve got some literature on our front table.

We proudly count David Bloom, the NBC correspondent who recently died in Iraq, as one of our members, and he certainly was a dear friend.

So, to tonight’s subject: belief in God in an age of science. In the last one hundred years or so, many people have come to think that somehow “modern man” ought to be beyond believing in God. This idea has continued to enjoy a kind of strangely unchallenged popularity and has rather dramatically affected our culture, often negatively, as is the case with many unchallenged assumptions. I thought it behooved us to apply a bit more rigor to our examination of this matter than we have generally applied, and tonight is meant as a small initial application of that selfsame rigor. And I can repeat that sentence.

It has come to my attention that for some of the very brightest minds on our planet, there is, in fact, no disparity between the truth as promulgated in the biblical faiths and the truth promulgated by scientific discovery. But, as I say, we don’t often hear from those bright minds, and I’m very happy to remedy that tonight, with, if I may say so, one of the brightest. I think no matter where you come out on this issue, it will do us all kinds of good to hear from our guest speaker tonight, Sir John Polkinghorne.

I first came to hear Dr. Polkinghorne in Cambridge, England, just over a year ago at a C. S. Lewis conference that was held at Oxford and Cambridge universities. As luck would have it, Oxford and Cambridge universities are located in Oxford and Cambridge, England, respectively. It is all a little too neat, isn’t it?

In any case, I was very taken with Dr. Polkinghorne, and I asked him to come to New York City and speak at Socrates. And, of course, here he is.

Now, I have to say that we have never had a Knight of the British Empire at Socrates in the City, at least not that I know of. I’m not quite sure what the protocol is exactly. I assumed that the fact that Dr. Polkinghorne was a knight didn’t mean he would necessarily be wearing armor. Just to be on the safe side, I asked him not to wear any armor. It seems that he has complied with my request, unless he’s hiding a Kevlar vest under there, which we will never know.

But I said to him that if he did feel compelled to wear armor, he might at least wear his beaver up, like Banquo’s ghost in Hamlet, so that we might better hear what he had to say.

Thank you to all the Banquo fans out there for laughing at that.

A bit of a word on our format. Dr. Polkinghorne will speak for about thirty-five to forty minutes, and then we will have plenty of time for questions and answers. If you have a question, I implore you, please, to step to the microphone here. I implore you to be brief and to speak clearly— and to end your question with a proper punctuation mark. I think you know what I mean.

Nothing like a punctuation-mark joke to get the crowd warmed up.

Now, to introduce the Reverend Dr. John Polkinghorne, KBE, FRS, DDS, Notorious B.I.G. That’s a typo. That’s a hip-hop joke. I don’t expect you to get it, Dr. Polkinghorne.

In any case, the Reverend Dr. John Polkinghorne comes to us from Cambridge University, England. He is a fellow of the Royal Society; a fellow and former president of Queens College, Cambridge; and Canon Theologian of Liverpool Cathedral.

Dr. Polkinghorne is married to Ruth Polkinghorne. They have three children: Peter, Isabelle, and Michael. Dr. Polkinghorne’s distinguished career as a physicist began at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied under Dirac and others. He became a professor at Cambridge in 1968. In 1974, he was elected fellow of the Royal Society. During that time he published many papers on theoretical, elementary particle physics in learned journals. If it sounds as if I know what I am talking about, I just want to say I got a 1 on my AP physics exam. That is not a good score.

In 1979, Dr. Polkinghorne resigned his professorship to train for the Anglican priesthood. He served as curate in Cambridge and Bristol, and was vicar of Blean from 1984 through 1986.

In 1986, he was appointed fellow, dean, and chaplain at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. In 1989, he was appointed president of Queens College, Cambridge. His own words in reaction to this honor from his official bio: “You could have knocked me over with a feather.” That is actually in the bio. You can go online and look that up.

I have to say that I’m surprised that particularly as a top physicist, Dr. Polkinghorne would have been so naive as to believe that someone might have actually knocked him over with a feather— even a very, very, very large feather. One from an emu or ostrich, perhaps, would hardly be able to knock over an average-sized adult male, even if he were temporarily stunned by his appointment to the presidency of a Cambridge college. As I say, even I, as a non-physicist, who got a 1 on his AP exam, know that, and I am embarrassed to report that Dr. Polkinghorne, with all his fancy degrees and honors, somehow did not know that.

Given Dr. Polkinghorne’s weight and any reasonable μ [“mu”] friction coefficient, I think the idea of his being knocked over by a feather is patently and demonstrably absurd. But I’m sure that by now, he has repented of the statement.

In any case, Dr. Polkinghorne retired as president of Queens College in 1996. He is a member of the General Synod of the Church of England and of the Medical Ethics Committee of the British Medical Association.

He was appointed KBE— Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire— in 1997. Now, a word to the wise: I am told that like many knights, Sir John is handy with a broadax, and if you aren’t in full agreement with his talk tonight, he might very well be forced to smite you or cleave you, as the case may be.

As most of us know, Dr. Polkinghorne has published a series of remarkable books on the compatibility of religion and science. These began with The Way the World Is. He said, “It was what I would have liked to have said to my scientific colleagues who couldn’t understand why I was being ordained.” The Way the World Is is available on our book table. It’s a fabulous book.

Just last year, Dr. Polkinghorne won the prestigious— very prestigious— Templeton Prize for progress in religion. The award has previously been awarded to such figures as Mother Teresa and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Contrary to popular belief, it has never been awarded to Sir Elton John or to Sting. Glad to clear that up for some of you.

So, let me say then what a pleasure it is now to welcome to this podium at Socrates in the City— Sir John Polkinghorne.

Talk (#ulink_a869992f-869b-5780-9281-7ece8a971b60)

Oh, dear, what an act to follow. Let me say, I’m very pleased to be here to try to stumble along in Eric’s wake.

You gather that I am someone who wants to take science absolutely seriously, and I think that we are right to do so in this age of science. I am also someone who wants to take religion, particularly my own religion, Christianity, absolutely seriously as well. I believe that I can do that, not, of course, without puzzles occasionally, but without intellectual dishonesty and, indeed, with some degree of mutual enhancement, because it seems to me that science and religion have one extremely important thing in common— they both are concerned with the search for truth.

The question of truth is as important to religion as it is to science. Religion can do all sorts of things for you. It can comfort you in life and in death, but it cannot do any of those things unless it is actually true. Of course, science and religion are looking for different aspects of the truth.

Science has purchased its very great success by the modesty of its ambition. Science does not seek to ask and answer every sort of question. It restricts itself essentially to asking questions of process, which are “how questions” of how things come to be. It also restricts the kind of experience that it takes into account in framing and finding its answers to those questions. Science treats the world as an object, as an it, as something that you can put to the experimental test, that you can pull apart to see what it is made of, and we have learned all sorts of very significant things by doing that.

We also all know that there is a whole realm of human experience— personal experience— and, I would wish to add, the chance personal experience of encounter with the sacred reality of God, a realm of experience in which testing has to give way to trusting. If I’m always setting little traps to see if you are my friend, I would destroy the possibility of friendship between us. Religion is asking a different set of questions, deeper questions, and, in my view, more interesting questions, even than those of science— questions of meaning and purpose: “Is there something going on in what is happening in the world?”

So, there are lots of questions, it seems to me, that are necessary to ask and meaningful to ask, but which are just not scientific questions in their character and, therefore, are questions which science by itself is unable to answer. Interestingly enough, some of those questions arise from our experience of doing science but take us beyond science’s self-limited power of inquiry. You might call them meta-questions— questions that take us beyond.

I want to start by considering briefly with you two of those meta-questions, and the first one is this. It’s a very simple question, so simple, in fact, that most of the time, we don’t even stop to think about it, but I think it’s worth thinking about. It is simply this: Why is science possible at all? In other words, why can we understand the physical world in which we live?

“Well,” you might say, “that’s pretty obvious. We’ve got to survive in the world. If we don’t understand the world, we’ll soon come a cropper [British term meaning ‘run into trouble’].”

Of course, that’s true up to a point. It is true of everyday knowledge and everyday experience. If we couldn’t figure out that it’s a bad idea to step off the top of a high cliff, then we would not stay around for very long. We would stay around a bit longer in my part of the world, which is extremely flat. Nevertheless, we would obviously come to grief.

But it does not follow from that everyday practicality that somebody like Isaac Newton can come along and, in a quite astonishing, imaginative leap, see that the same force that makes the high cliff dangerous is also the force that holds the moon in its orbit around the Earth and the Earth in its orbit around the sun and discover the mathematically beautiful law of universal inverse square or gravity, and in terms of that can explain the behavior of the whole solar system. Of course, back two hundred years after Newton, Einstein comes along and discovers general relativity, which is the modern theory of gravity; then, in terms of that, he is able to explain not just our little local solar system but to frame the first genuinely scientific cosmology account of the whole universe. Incidentally, he got it wrong, but that is another story.

So, why do we have this amazing power? I worked in quantum physics, in small-particle physics, the smallest bits of matter, and the quantum world is totally different from the everyday world. In the quantum world, if you know where something is, you don’t know what it’s doing. If you know what it’s doing, you don’t know where it is. That’s the high-and-low of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in a nutshell. That world is totally different from the everyday world, and if we are to understand it, we have to think differently about it. But we have learned how to do that. We have powers to understand the world that greatly exceed anything that could be considered as just a survival necessity, just a mundane necessity, or, indeed, be considered as some happy additional spin-off from necessities of that kind.

I don’t know whether you are a Sherlock Holmes fan, but I hope you might be, and if you are, you will remember that when Holmes and Watson first meet each other, they’re having breakfast in a London hotel, and right from the start, Holmes is pulling Watson’s leg. He says to Watson, “I don’t know, I don’t know. Does the earth go around the sun? Or does the sun go around the earth?” The good doctor is horrified at this deplorable scientific ignorance, and Holmes just says, “Well, what does it matter for my daily work as a detective?” It doesn’t matter at all, but we all know many, many things. Science has told us many, many things that are actually intellectually satisfying to know and that are certainly not connected with the certainties of everyday life.

So, why is science possible? Why can we understand the world so thoroughly and so profoundly? In fact, the mystery is greater than that even, because it turns out that mathematics is the key to unlocking the secrets of the physical universe. It’s an actual technique in fundamental physics to look for theories whose mathematical expression is in terms of beautiful equations. Some of you will know about mathematical beauty, possibly not all of you. It’s a rather austere form of aesthetic pleasure but something that those of us who speak the language of mathematics can recognize and agree upon. This is the experience of three hundred years of doing theoretical physics in which the theories that fundamentally describe the world always turn out to be framed in terms of beautiful equations. It’s an actual technique of discovery to look for equations of that sort.

The greatest theoretical physicist I’ve known personally was Paul Dirac, one of the founding figures of quantum theory and a professor in Cambridge for many years. He was not a religious man, nor a man of many words. He once said, “It is more important to have beauty in your equations than to have a fit experiment.”

Of course, by that, he didn’t mean it didn’t matter, or [that] empirical adequacy is a dispensable thing in science. No scientist could possibly mean that, but if you had a theory and it didn’t look as though, at first sight, your equations were going to fit the experiment, there were just possibly some ways out of it. Almost certainly you would have had to solve the equations in some sort of approximation. Maybe you made the wrong approximation or you hadn’t gotten the right solution or maybe the experiments were wrong. We’ve learned that more than once, I have to say, in the history of science. But if your equations were ugly, there was no hope for you. They could not possibly be right.

Dirac was, undoubtedly, the greatest British theoretical physicist of the twentieth century. He made those discoveries due to a relentless and highly successful lifelong pursuit of beautiful equations.

Now, something funny is happening there. We’re using mathematics, which, after all, is a very abstract form of human activity, to find out about the structure of the world around us. In other words, there seems to be some deep-seated connection between the reason within— the mathematical thoughts in our minds, in this case— and the reason without, which is the path and order of the physical world.

Dirac’s brother-in-law, Dr. Eugene Wigner, who also won a Nobel Prize in physics, once asked, “Why is mathematics so unreasonably effective?”

Why does the “reason within” apparently perfectly match the “reason without,” that is, the wonderful order of the world in which we live? That’s a deep question, a meta-question, and those sorts of questions do not have simple knocked-out answers. They are too, too profound for that, but for me, a highly intellectually satisfying answer is the following: The reason within and the reason without fit together because, in fact, they have a common origin in the rational mind of the Creator, whose will is the ground both of our mental experience and the physical world of which we are a part.

You could summarize what I have been trying to say so far by saying that as physicists study the world, they study a world of wonderful order, a world shot through, as you might say, with signs of mind. If that’s so, then it seems to me it’s, at least, a hypothesis worth considering, because, in fact, the capital-M Mind of the Creator lies behind that wonderful order. I, in fact, believe that science is possible, that the world is deeply intelligible, precisely because it is a creation. To use ancient and powerful language, we human beings are creatures made in the image of our Creator. The power to do theoretical physics is a small part— a small part, no doubt— of the imago Dei [image of God].

So, that is one sort of meta-question, and it illustrates the way our religious belief and understanding does not tell science what to think in its own domain. We have every reason to believe that scientifically presentable questions will receive scientifically articulated answers, even though some of those answers may prove very difficult to find. But the meta-questions take us beyond science, and it seems to me that religion can provide intellectually satisfying and coherent responses, enabling science to be set within a wider and more profound setting of intellectual intelligibility.

I would like to ask a second meta-question: Why is the universe so special? Scientists do not like things to be special. Our instinct is to like things to be general, and our natural assumption would be that the universe is just a common-variety garden specimen of what our universe might be like— nothing very special about it. But as we’ve studied and understood the history of the universe, we’ve come to realize we live in a very remarkable universe, indeed, and if it was not as remarkable as, in fact, it is, we would not be here to be struck at the wonder of it.

The universe started extremely simply; 13.7 billion years ago is the rather accurate figure that cosmologists say. It started as almost a uniform expanding ball of energy, which is about the simplest possible physical system you could ever think about. One of the reasons why cosmologists talk with a certain justified boldness about the fairly early universe is because it is a fairly easy thing to think about. But our world is not so simple; it has become rich and complex, and after almost fourteen billion years, it has become the home of saints and mathematicians. We’ve come to realize, as we understood the steps by which that has happened, that though it took a long time— as far as we know, ten billion years for any form of life to appear and fourteen billion years for self-conscious life of our complexity to appear— nevertheless, the universe, in a very real sense, was pregnant with life from the very beginning. It is, in this sense, that the physical fabric of the world— that is, the given laws of nature that science uses as the basis of its exploration of what is going on, but whose origin science itself is unable to explain, which are the unexplained given, in terms of which science frames all its subsequent explanations— had to take a very precise, very finely tuned form, if the evolution of any form of carbon-based life, like ourselves, was to be a possibility in cosmic history.