По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

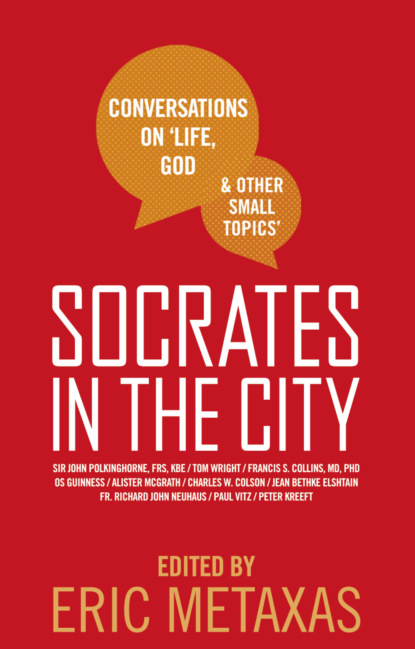

Socrates in the City: Conversations on Life, God and Other Small Topics

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Of course, the evolution of life, the evolution of the universe, was an ongoing process, but evolution by itself has to have the right material to act upon. Unless the physical fabric of the world was finely tuned for the possibility of carbon-based life, the universe could have evolved away forever, and nothing interesting would have happened. This history would have been boring and sterile in the extreme. So, we live in a very special world.

Let me just give you a couple of illustrations of why we think that is so. There are many, many arguments that point in that direction. I could spend all evening trying to list them, but I won’t do that. I’ll just give you a couple of examples. The first example is this: The very early universe is very simple, and so, it does only very simple things. For the first three minutes of the universe’s life, the whole universe is immensely hot, immensely energetic. It is a sort of cosmic hydrogen bomb with nuclear reactions going on all the time.

As the universe expanded, it cooled. After just about three minutes, the universe was so sufficiently cooled that nuclear reactions on a universe-wide scale, on a cosmic scale, ceased, and the gross nuclear structure of the world was frozen out as, in fact, what we see it to be today, which is three-quarters hydrogen and a quarter helium. The early universe was very simple and made only very simple things. It made only the two simplest chemical elements, hydrogen and helium, and those two elements have a very boring chemistry. There is nothing very much that you can do with them.

The chemistry of life actually requires about thirty elements, of which possibly the most important is carbon. We call ourselves, when we think about it, carbon-based life. The reason for that is that carbon is the basis of those very long-chain molecules, and the chemical properties of carbon seem to be necessary for living entities. But the early universe has no carbon at all. So, where did carbon come from?

As the universe began to get a bit clumpy and lumpy as gravity began to condense things, stars and galaxies began to form. Then, as the stars formed, the matter inside the stars began to heat up, and nuclear reactions began again, no longer on a cosmic scale, no longer universe-wide, but in the interior nuclear furnaces of the stars. It is here in the interior nuclear furnaces of the stars that all heavy elements— there are ninety of them altogether and about thirty of them necessary for life— were made beyond hydrogen and helium.

One of the great triumphs of the second half of the twentieth century in astrophysics was working out how those elements were made by the nuclear reactions inside the stars. One of the persons who played an absolutely leading role in that was a senior colleague of mine in Cambridge called Fred Hoyle. Fred was with Willy Fowler from Caltech— they were thinking together about how these things might happen, and they were absolutely stuck at the start.

The first element they really wanted to make was carbon, and they could not for the life of them see how to make it. They had helium nuclei— we call them alpha particles— around. To make carbon, you have to take three alpha particles and make them stick together. That turns helium-4 into carbon-12, and that is a very, very difficult thing to do. The only way to do it is to get two of them and make them stick together. First of all, that makes beryllium, and then you hope that beryllium stays around for a bit. A third alpha particle comes wandering along and eventually sticks on and makes carbon-12. Unfortunately, it does not work in a straightforward way, because beryllium is unstable and does not oblige you by staying around to acquire that extra alpha particle.

So, Fred and Willy really could not figure out how to do it. On the other hand, there they were, carbon-based life, thinking about these things: It must be possible to make carbon. And then Fred had a very good idea. He realized it would be possible to make some carbon out of even this very transient beryllium if there was an enhancement— what, in the trade, we call a resonance— present in carbon that would produce an enhanced effect. That is, it would make things go much, much more quickly than you would expect. However, you not only had to have a resonance but also had to have it at the right place; it had to be at the right energy for this process to be possible. If it were anywhere else, it would not affect the rate at which things happen.

So, Fred is convinced that there must be a resonance in carbon at precisely this energy and writes down what the energy is. The next thing, he goes to the nuclear data tables to see if carbon had such resonance, and it is not in the nuclear data tables. Fred is so sure it must be there that he rings up his friends the Laurences, who are very clever experimentalists at Caltech, and says to them, “You look. You missed the resonancy in carbon-12, and I’ll tell you exactly where to look for it. Look at this energy, and you’ll find it.” And they did— a very staggering scientific achievement. It was a very, very great thing, but the point is this: That resonance would not be there at that absolutely unique and vital energy if the laws of nuclear physics were in the smallest degree different from what they actually are in our universe.

When Fred saw that and realized that— Fred has always been powerfully inclined toward atheism— he said, in a Yorkshire accent, which, I am afraid, is beyond my powers to imitate, “The universe is a put-up job.” In other words, this cannot be just a haphazard accident. There must be something lying behind this. And, of course, Fred does not like the word God; he said there must be some capital-I Intelligence behind what is going on in the world. So, there we are; we are all creatures of stardust. Every atom of our bodies was once inside a star, and that is possible because the laws of nuclear physics are what they are and not anything else.

Let me give you just one more example of fine-tuning. This is the most exacting example of all. It is possible to think of there being a sort of energy present in the universe, which is associated simply with space itself, and that energy these days is usually called dark energy. It used to be called the cosmological constant, but it has come to be called dark energy, because just recently astronomers believe they have measured the presence of this dark energy. In fact, it is driving the expansion of the universe.

What is striking about that expansion is that this energy is very, very small, compared to what you would expect its natural value to be. You can figure out— now, I won’t go into the details— what you would expect the natural value of this energy to be. If you’re in the trade, it is due to vacuum effects and things of that nature, but it turns out that the observed dark energy— if the observations are correct— is ten to the minus-120 times the natural expected value (10

); that’s one over one followed by 120 zeroes.

Even if you’re not a mathematician, I am sure that you can see that is a very small number indeed. If that number were not actually as small as it is, we would not be here to be astonished at it, because anything bigger than that would have blown the universe apart so quickly that no interesting things could have happened. You would have become too diluted for anything as interesting as life to be possible.

So, there are all these sorts of fine-tunings present in the world. All scientists would agree about those facts. Where the disagreements come, of course, is in answering the meta-question: What do we make of that? What do we think about the remarkable character of the world, the specific character of the world? Was Fred right to think that the universe is, indeed, a put-up job and that there is some sort of Intelligence behind it all?

I am sure you all know that these considerations about the fine-tuning of the universe are called the anthropic principle— not meaning that the world is tuned to produce literally Homo sapiens, but anthropoi, meaning beings of our self-conscious complexity. I have a friend who thinks about these things and has written, I think, the best book about the anthropic principle, Universes. His name is John Leslie. He’s an interesting chap because he does his philosophy by telling stories, which is very nice. He’s a parabolic philosopher. That is very nice for chaps like me who are not trained in philosophy, because everybody can appreciate a story, and he tells the following story:

You’re about to be executed. You are tied to the stake, your eyes are bandaged, and the rifles of ten highly trained marksmen are leveled at your chest. The officer gives the order to fire, the shots ring out, and you find that you have survived. So, what do you do? Do you just walk away and say, “Gee, that was a close one”? I don’t think so. So remarkable an occurrence demands some sort of explanation, and Leslie suggests that there are really only two rational explanations for your good fortune.

One is this: Maybe there are many, many, many executions taking place today. Even the best of marksmen occasionally miss, and you happen to be in the one where they all miss. There have to be an awful lot of executions taking place today for that to be a workable explanation, but if there are enough, then it is a rational possibility. There is, of course, another possible explanation: Maybe there is only one execution scheduled for today, namely yours, but more was going on in that event than you are aware of. The marksmen are on your side, and they missed by design.

You see how that charming story translates into thinking about the anthropic fine-tuning— the special character of the universe in which we live. First of all, we should look for an explanation of it. Now, of course, obviously, if the universe was not finely tuned for carbon-based life, we, carbon-based life, would not be here to think about it. But the coincidence is that the fine-tunings required are so specific and so remarkable that it is no more sensible for us to say, “We’re here because we’re here, and there’s nothing more to talk about it,” than it would be for that chap who missed being executed to say, “Gee, that was a close one.” So, we should look for an explanation.

Basically, there are two possible explanations. One is that maybe there are just many, many, many different universes— all with different laws of nature, different kinds of forces, different strengths of forces, and so on. If there are enough of those universes— and there would have to be a lot of them, an enormous number of them— but if there are enough of them, then, of course, by chance, one of them will be suitable for carbon-based life. It will be the winning ticket in the cosmic lottery, as you might say, and that, of course, is the one in which we live, because we are carbon-based life. That would be a many-universes explanation.

Of course, there is another possibility. Maybe there is only one universe that is the way it is, because it is not just any old world but is a creation that is being endowed by its Creator with precisely the finely tuned laws and circumstances that will allow it to have a fruitful history.

So, many, many, many universes or design, a created design. Which shall we choose? Leslie says we don’t know which one to choose. It is six of one and half a dozen of the other. I think in relation to what I have just been talking about— these anthropic fine-tunings— that Leslie is right about that. Both suggestions are what you might call metaphysical. Sometimes, people try to dress the many universes all up in scientific vestment, but essentially I think it is a metaphysical guess. We do not have direct experience of those many, many, many universes. That is a sort of metaphysical guess, just as the existence of a Creator God is a sort of metaphysical guess. So, what should we choose?

If that is the only thing we are thinking about, we can choose one or the other with equal plausibility, but if we widen the argument, then I think we shall see that the assumption that there are many, many, many universes does only one piece of explanatory work. The only thing it explains is to explain away the particularity of our observed and experienced universe. The piece of work is to diffuse the threat of theism, but the theistic explanation— it does seem to me— does a number of other pieces of work.

I have already suggested that a theistic view of the world explains the deep intelligibility of the world that science experiences and exploits, and I also believe, of course, that there is a whole swath of religious experience of the human-testified encounter with the reality of the sacred, which is also explained by the belief in the existence of God. So, it seems to me, there is a cumulative case for theism in which the anthropic argument can play one part, but only one part. It will not, of course, surprise you, given what you know about me, that it is that latter explanation which I myself embrace.

There we are. That is one aspect of the relationship between science and religion. The intelligibility of the world and the particular fruitfulness of the universe are striking things that science draws to our attention but does not itself explain. It seems to me that religion can offer science the gift of a more extensive, more profound understanding to set the remarkable results of science within a more profound matrix of understanding.

Science also, it seems to me, gives gifts to religion. The gifts that science principally gives to religion are to tell religion what the history and the nature of the world are like and have been, and religious people should take that absolutely seriously. Those seeking to serve the God of truth should welcome truth from whatever source it comes, not that all truth comes from science, of course, by any means. But real truth does come from science, and we should welcome that. The truth of science, in my view, is able to help religion with its most difficult problem.

What is the most difficult problem for religion? What holds people back from religious belief more than any other? What troubles those of us who are religious believers more than any other? I am sure we are likely to agree that it is the problem of the suffering that is present in the world— the disease and disaster that seems to be present in what is claimed to be the creation of a good and perfect and powerful God. I do not need to explain what that problem is. It is only too clear.

Interestingly enough, the insights that science offers— the world is an evolving world, and evolutionary thinking is fundamental to all scientific thinking about the history of the universe, not just the evolution of life here on Earth— is, of course, part of the story. But the evolving part of the universe itself— the processes by which the galaxies and the stars formed and so on— all of these are evolutionary processes.

It is interesting that when Darwin publishes his great work On the Origin of Species in 1859, there is a sort of popular, absolutely, totally, historically ignorant view that that was the moment of the fantastic head-on collision between science and religion, with all the scientists shouting, “Yes, yes, yes!” and all the religious people, the clergy particularly, shouting, “No, no, no!” That’s absolutely, historically untrue!

There was a good deal of argument and confusion on both sides of the question. Quite a lot of scientists had lots of difficulties with Darwin. It was only when Mendel’s discovery of genetics was rediscovered and the neo-Darwinian synthesis came along that people really began to see and feel on surer ground in relation to it.

Equally, there were religious people who from the start welcomed the insights of evolutionary thinking into the nature of God’s creation. I am happy to say that two of those people who welcomed that were Anglican clergymen in England. One was Charles Kingsley, and the other was Frederick Temple, and they both coined the phrase that, I think, perfectly encapsulates the theological way to think about an evolving world. They said, “No doubt, God could have snapped the divine fingers and brought into being a ready-made world, but God had chosen to do something cleverer than that. For in bringing into being an evolving world, God had made a creation in which creatures could make themselves.”

In other words, from a theological point of view, evolving process is the way in which creatures explore and bring to birth the deep fruitfulness of potentiality with which the Creator has endowed creation. That gift of being themselves, making themselves, is, I think, what you would expect the God of love to give to that God’s creation. The God of love will not be the puppet master of the universe, pulling every string.

So, I think that a creation making itself, an evolving world which is a creation making itself, is a greater good than a ready-made world would be. However, it is a good that has a necessary cost, because that process of shuffling exploration of potentiality will necessarily involve ragged edges and blind alleys. The engine that has driven, for example, the evolution of life here on Earth has been genetic mutation in germ cells that have produced new forms of life, but the same biochemical processes that enabled germ cells to mutate and to produce new forms of life will necessarily allow somatic cells, body cells, also to mutate and become malignant. You cannot have one without the other.

So, the fact that there is cancer in the world, which is, undoubtedly, an anguishing aspect of the world and a source of grief and anger to us, is, at least, not gratuitous. It is not something that a God who was a little more compassionate or a little more competent could easily have removed. It is the shadow side of the creativity of the world. It is the necessary cost of a creation allowed to make itself. Now, you could argue whether it is a cost worth paying. I am not suggesting for a minute that this consideration I have been laying out in the last couple of minutes solves all the problems of evil and suffering, but it does at least help us. I say that it seems to indicate these problems are not gratuitous.

We all tend to think that if we had been in charge of creation, we would have done it better. We would have kept all the nice things (the sunsets, the flowers) and thrown away all the nasty things (the disease and disaster), but the more scientifically we actually understand the processes of the world, the more we see how inextricably interlinked all these things are and that there is a dark side as well as a light side to what is going on. That is a small hope, a small help, in relation to what is going on.

I always finish what I have to say, and the conversation will be the most interesting part of the evening. If you are totally convinced by everything I have said this evening, it would have led you no more than to a picture of God as the great mathematician or the cosmic architect. It has been a limited form of inquiry, and there is still much more that one might ask about the nature of God and much more that one might seek to learn about the nature of God; that will have to be found in other forms of human experience. A very important aspect of belief in God is that not only is there a Being who is the Creator of the world, but also this Being is worthy of worship, and I just indicate with a tiniest sketch how I would approach that issue.

I am deeply impressed by the existence of value in the world— something that science directly does not take into account. But our physical world, of which we are a part, is shot through with value, with beauty. For example, music is very interesting. Suppose you ask a scientist as a scientist to tell you all he or she can about music. They will say, “It is neuro-response— neurons firing away to the impact of vibrations in the air hitting the eardrum,” and, of course, that is true and, of course, in its way, it is worth knowing. However, it hardly tells you all you might want to know about the deep mystery of music. Science trolls experience with a very coarse-grained net, and the fact that these vibrations in the air somehow are able to speak to us— and, I believe, speak truly to us of a timeless beauty— is a very striking thing about the world.

Similarly, I think we have moral knowledge of a surer kind than any that we possess. I do not, for a minute, believe that our conviction that torturing children is wrong is either some kind of curious, disguised genetic strategy or just a convention of our society. Our tribe just happens to choose not to torture children. It is a fact about the world that torturing children is wrong. We have moral laws. Where do these value-laden things come from? I think they come from God, actually. Just as I think that the wonderful order of the world and the fruitfulness of cosmic history are reflections of the mind and purpose of the Creator, so I think that our ethical intuitions, our intimations of God’s good and perfect will, and our aesthetic experiences are a sharing in the Creator’s joy in creation.

For me, theistic belief ties together all these things in a way that is deeply satisfying and intellectually coherent, and then there would be many other questions still remaining. Even if there is such a God worthy of worship, does that God care for you and me? That is a question I could not answer without looking into taking the risk both of commitment and ambiguity and looking into personal experience. For me, that would mean looking into my Christian encounter with the person and reality of Christ. That is a subject for another discussion.

Here I am. I stand before you as somebody who is both a physicist and a priest. I am grateful for both of those things, and I want to be two-eyed. I want to look with the eye of science on the world, and I want to look with the eye of my Christianity on the world. The binocular vision those give me enables me to see and understand more than I would be able to with either of them on their own.

But it would be nice to know what you think about these things, and I think the time has come to let you have a go. So, over to you.

Q & A (#ulink_3a0e420e-1983-5317-bfca-cf3ab0c69a8f)

Well, thank you, Dr. Polkinghorne. I am sure there are people here who have questions. I am sure I know some of them personally. If anyone has a question or comments, as long as they end in a question mark and are very brief, get in line. So, go ahead.

Q: You started your speech stating that a common denominator of science and religion is the search for truth. When I was in school, I learned that the basis of science is the search for proof, not truth. So, I was waiting in your speech for some kind of sentence to the question about how you can prove that there is God. You know that this is the core question, and I am kind of missing that.

A: I think that is a very interesting comment to make. I think that we have learned that all forms of rational inquiry are a little bit more subtle than concluding with knockdown proof, knockdown argument. Even in mathematics, Kurt Gödel taught us that any mathematical system of sufficient complexity to include arithmetic, which means the whole numbers, will contain statements that can be made which can neither be proved nor disproved within that system. So, there is all openness, even in mathematics. In fact, a little act of faith is involved in committing myself to the consistency of a mathematical system. It cannot be demonstrated.

Not many people lie awake at night worrying about the consistency of arithmetic, but nevertheless, that is the case. So, I think we have learned that the proof in the knockdown rationale of the clear and certain ideas of the Enlightenment program which Descartes put on the agenda is a glorious, magnificent program, but it is a failure. No form of human life has that kind [of proof]. Science, though it certainly produces convincing theories, does not, I think, produce proof.

In my view, the greatest philosopher of science was Michael Polanyi, who was a very distinguished physical chemist before he became a philosopher and knew science really from the inside. In the preface to his famous book called Personal Knowledge, he says, “I am writing this book”— and he is writing about science, remember— “to show how I may commit myself to what I believe to be true, knowing that it might be false.” I think that is, actually, the human situation.

What I think we are looking for— and what I am looking for in my scientific searches and in my religious searches— is motivated belief. I believe that the success of science and also the illuminating power of religion encourage the idea that motivated belief is sufficiently close to truth for us to commit ourselves to it. But, I think, proof is actually not the category that we might think it is.

Q: I had the fortune to meet Stephen Hawking at Caltech, and I had a question for him about the coded information that is in the biological world (and he wouldn’t answer): did he believe in God? I was wondering, with your having been at Cambridge, what your thoughts were about his thoughts on that.

A: Stephen and I were colleagues in the same department for many years. It’s not easy to have a conversation with Stephen, because it is so laborious for Stephen to produce things. When he does give an answer, he tends to say, “Yes,” or “No.” While the rest of us say, “We think of it this way, or maybe that way,” he just can’t do that with the handicap he has fought against so remarkably.