По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

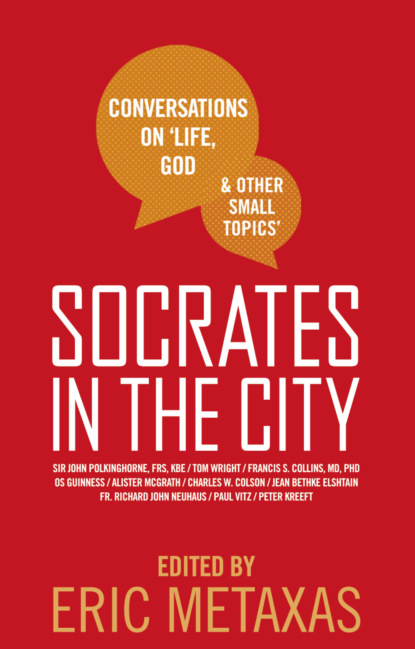

Socrates in the City: Conversations on Life, God and Other Small Topics

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Making Sense out of Suffering (#ulink_fbba82db-c4e4-5fa4-9956-7b991bb294cd)

PETER KR EEFT

January 23, 2003

Introduction (#ulink_e2382a41-15b3-59a5-97ea-42dcfea07cf9)

Good evening and welcome to Socrates in the City. I am Eric Metaxas. Socrates in the City takes its name from Socrates, who, of course, famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Then he drank the hemlock and died.

Do I have that out of order? Oh, right. He said, “The unexamined life is not worth living,” at some point earlier in his career, and he said it in a very positive way, meaning that we are to examine our lives. Of course, I think he was quite right.

We are, indeed, to examine our lives. It makes life much more worth living. So, a bunch of folks, most of them friends of mine, and I were thinking that most New Yorkers are so busy that we don’t really take out the time in our lives to examine our lives with any particular rigor. We thought that putting on these events called Socrates in the City and inviting speakers like Dr. Kreeft to address some of the big issues of life would be advisable.

It actually turns out that we were dead wrong. These have been a disaster, and I think this will be the last one we do. I’m glad you’re laughing.

These have been really extraordinary. I have to say I am humbled by the turnout tonight. The turnout has been consistently good, the speakers have been wonderful, and these things have been as successful as I have hoped. In any case, we call these events Socrates in the City: Conversations on the Examined Life, and they are meant to be conversations, not only in the question-andanswer that follows the talk but also after these events, when we leave from here. We hope that we have begun a conversation in your mind and that you will be thinking about these things beyond this evening.

In any case, you can’t go wrong following Socrates’s advice on the matter of examining your life. Of course, Socrates didn’t have to pay New York rent and could spend all his time thinking about his life. But you get the idea—and it is a good idea—and we are thrilled you can be here tonight to do it with us.

Tonight, we are privileged to have the estimable Dr. Peter Kreeft with us. Dr. Kreeft is a philosophy professor at Boston College, which, I am told, is located in Boston— is that right?

He is also a very, very much sought-after speaker. Believe me, it was very difficult to get him; we are lucky to have him. He has written many books— over forty— and many bestsellers among them. Most notably for tonight, he has written an absolutely fabulous book titled, appropriately enough, Making Sense out of Suffering, and of course, that will be his subject.

The goal of Socrates in the City is to attack the big questions— the biggest questions of all: about the existence of God, what it means to be human, about evil and suffering, and about where we come from and where we are going. We shouldn’t be scared by those questions.

Living in New York, you sometimes get the idea that the biggest questions we deal with are along the lines of “Do I take the cab or the subway?” Or, if I am on the second floor, “Do I take the elevator or do I walk down?” That is a big one for me.

For Boston, where Dr. Kreeft is from, I think one of the big questions that have really been in the minds of Bostonians and the people in Massachusetts for a long time now is “Why did Dukakis wear that absurd helmet?” I don’t think there is an answer. It is almost a rhetorical question, isn’t it? I don’t think there is an answer.

Another question Bostonians have, of course, is “Why can’t the Boston Red Sox

(#ulink_39b6a709-1ef9-531d-aa64-700f57d1c952) get it together and win the World Series?” I am sorry; that is probably below the belt. Dr. Kreeft, please don’t leave. You have to keep in mind that I am a Mets fan; I was born in Queens. So, we are brothers in our disdain for the Yankees. It is a bond that we share as a Mets fan and a Red Sox fan. Let’s just pretend that the Bill Buckner thing never happened, and we will just be friends.

Anyway, tonight we are here to ask a big philosophical question. Woody Allen, in his writings, always had a knack for putting the huge philosophical questions right up alongside the picayune, practical problems of life. There are a couple of things that he wrote along these lines that I love, and I wanted to share them with you this evening. For example, he wrote, “Can we actually know the universe? My goodness, it is hard enough finding your way around in Chinatown.” That’s such a typical Woody Allen line that it’s almost not funny, right?

He also said, “The universe is merely a fleeting idea in God’s mind— a pretty uncomfortable thought, particularly if you just made a down payment on a house.” And this is my favorite; it’s more apocalyptic than it is philosophical. He wrote, “The lion and the lamb will lie down together, but the lamb won’t get much sleep.”

You’ll never be able to stop thinking of that. I wish I had written it. Anyway, perhaps one big question many of us have here tonight is whether the speaker’s name is pronounced “Kreeft” or “Krayft.” At least it was for me. In dealing with Dr. “Krayft” over the phone, I have come to hear him say “Krayft” a number of times, and I just sort of assumed he would know. So, whether he is right or wrong, we will just follow his lead and drop that question going forward.

Seriously, folks, I have been privileged to read a number of Dr. Kreeft’s books over the years, and I have to say that they are delightfully readable and lucid. I think that accounts for his extraordinary popularity as an author and as a speaker. I first heard Dr. Kreeft at Oxford University in England at the hundredth anniversary celebration of C. S. Lewis’s birth.

Indeed, many people have said that Dr. Kreeft’s writings remind them of C. S. Lewis’s. I would agree. Like Lewis, Dr. Kreeft attempts and succeeds wonderfully at making the complicated simple, at explaining some very big things to little people like me. For that I am very grateful, because I have to admit that even though I am of Greek descent, I have had some difficulty with philosophy.

I remember in my freshman year in college, I took a survey course in ancient philosophy and got stuck at Thales. Two people laughed. Thank you. I never really got past Thales, and I can guess that most of you in the room probably never did either. I am sort of under the impression that probably most of you never got to Thales.

Anyway, for those of you who didn’t know it, Thales was a pre-Socratic. Don’t feel bad if you didn’t know that he was a pre-Socratic, because Thales didn’t know it either. Yeah, keep thinking about that.

Enough silliness. Our subject tonight is for me and for most people the ultimate big question. This is a biggie, maybe the biggest. Tonight’s subject, of course, is how do we make sense out of suffering? I don’t know how many times I have heard someone say, “How can you believe in a loving God with all the suffering that there is in this world?”

I think that is a very valid question. I do believe in a loving God, but that is a very valid and difficult question. It is a brilliant question. I think it is the question of questions and, therefore, could not be more appropriate for this forum and for Dr. Kreeft’s attentions this evening. So, I hugely look forward to hearing Dr. Kreeft’s thoughts on it. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Peter Kreeft.

(#ulink_766eea32-bbf7-5b90-b746-c8665c611e15) At the time of Dr. Kreeft’s lecture, the Red Sox had not won a World Series since 1918; of course, this run of hard luck changed in 2004, when they beat the St. Louis Cardinals, breaking the eighty-six-year-old “curse of the Bambino.”

Talk (#ulink_394d2cec-e0bc-5efe-93db-6b3817aaf36d)

Usually an introduction is just an introduction. How can I follow that?

What a wonderful idea— Socrates in the City! And what a wonderful place! I am also humbled. This is the meaning of one of the beatitudes: “Blessed are the poor in spirit.” It doesn’t mean blessed are the cheap in spirit; it means blessed are those who have the opportunity to be in a J.P. Morgan room so they can be humbled in spirit.

(#ulink_538c4cbc-551b-58f2-846d-083e52e4506a)

Socrates in the City! Of course, New York deserves “the City,” but I don’t deserve “Socrates.” However, I am here because I am from Boston. Boston has more philosophers than any other city in the world, per capita. This is because philosophy is the love of wisdom. Wisdom comes through suffering. We have the Red Sox.

As for Billy Buckner, the morning after, I asked twelve close Red Sox fans how they felt when they saw that ball roll through his legs, and they all said one of two things. Number one: “Ashamed. How foolish I was. I hoped, I thought it was possible. What an idiot. I forgot the curse.” Or number two: “Happy. Suppose we had won? We’d be just like everybody else. We’re special. We’re the chosen people.”

I spent many years, months, hours in this great city. I was born in that place Woody Allen talks about in Love and Death— northern New Jersey. There’s a great dialogue between him and Diane Keaton. After she says, “Do you believe in God?” he says, “Well, on a good day like this, I could believe in a universal, divine Providence pervading all areas of the known universe, except, of course, certain parts of northern New Jersey.”

As to the problem of suffering, I love the line he speaks— I forget the title of the movie— he’s a Jewish father, his boy has become an atheist, and his wife blames him. So, she says to him, “Tell our son.”

“What’s the problem?”

“Well, he wants to know why there’s evil.”

“What do you mean ‘why there’s evil’?”

“Well, why there are Nazis. Tell him why there are Nazis.”

“I should tell him why there’s Nazis? I don’t even know how the can opener works,” which is quite profound, and I can’t do much better than that.

But let me play Socrates and do things logically: first, state the question; second, decide how important it is; third, explore the logic of the problem; and fourth, try to solve it.

I titled my book Making Sense out of Suffering. What is sense? Sense means an explanation. Unlike the animals, we don’t simply accept things as they are, unless we’re pop psychologists. We ask, we question, we wonder. We ask especially the question “Why?” When we’re adults, we usually ask it only once. That’s why adults are not philosophers.

Little children ask it infinitely, and that’s why they’re philosophers: “Mommy, why?” “Because . . .” “Because why?” They keep going.

Aristotle, the master of those who know, the most commonsensical philosopher in the history of Western philosophy, gave us one of the ideas that no one should be allowed to die without mastering— one of the ideas that is a requisite for a civilization— the so-called theory of the four causes. All possible answers to the question “Why?”— all possible becauses— fit into four categories.

I assume that you are all civilized, and therefore, I will insult you, but I have the privilege of insulting you for thirty-five minutes and making you sit through a purgatory of listening to a lecture, which is always dull. This way, you can get to the heaven of a longer question-and-answer session, which is always much more interesting, at least in my experience. Poor Socrates! The only time they made him make a speech, it cost him his life.

Number one, we can ask, “What is this thing?” Define it. What is its form, essence, nature, species? That’s the formal cause. Second, we can ask, “What is it made of, what’s in it, or what’s the content of it?” That’s what Socrates called the material cause. Third, we can ask, “Where did it come from? Who made it?” That’s what he calls the efficient cause. The fourth and most important and most difficult question we can ask is “What is it for? Why is it there? What purpose does it serve?” That’s what he called the final cause.

When we talk about suffering, there is not too much difficulty about the formal cause. We know what it is. The material cause is made of different things for different people. It’s made of the Yankees for Red Sox fans, or it’s made of the Red Sox for Yankees fans. But the efficient and the final causes are the mysteries— where did it come from, and what good is it, if any? These are absolutely central questions and can be seen by comparing a couple of thinkers.

Let’s start with Viktor Frankl’s wonderful book Man’s Search for Meaning, one of the half dozen books I would make everyone in the world read at gun-point, if I possibly could, for the survival of sanity and civilization. Frankl is a Viennese psychiatrist who survived Auschwitz but didn’t just survive it. He played Socrates at Auschwitz. He asked questions, for example, “What makes people survive?” And his answer is: Freud is wrong. It’s not pleasure. Adler is wrong. It’s not power. Even Jung is wrong. It’s not integration or understanding the archetypes or anything like that. It’s meaning. Those who found some meaning in their suffering survived, even though all the other indicators predicted that they wouldn’t. And those who didn’t— didn’t.

He writes, “To live is to suffer. Therefore, if life has meaning, suffering has meaning, too.” That seems to me to be utterly logical. The corollary is that if suffering does not have meaning, then life does not have meaning, because to live is to suffer.

He observed that different people had different answers to the question “Why are we suffering this absurd and agonizing thing?” But all the answers had one thing in common: They all turned a corner from asking the question “Life, what is your meaning?” to realizing that life was questioning them by name, “What is your meaning?” They could answer the question only by action, not just by thought, and those who believed in a God behind life asked the same question of God: “God, why me? What are you doing, and why?” Those that turned the corner realized that God was questioning them, which is exactly what happened to Job. When God showed up, he didn’t give answers; he gave questions. How Socratic God is!