По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

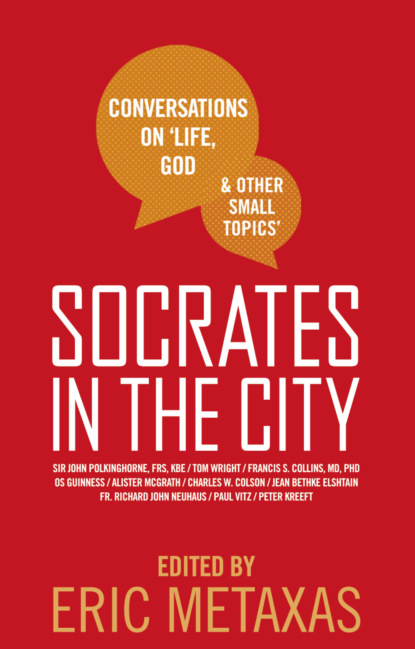

Socrates in the City: Conversations on Life, God and Other Small Topics

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Q: I have two questions that maybe you can expound on a little bit. The first is, isn’t there a difference between suffering and evil? And the second is, wouldn’t it be the case that evil is either the opinion of an infinite, perfect God or just every individual’s random opinion in that without God evil can’t really exist, and if somebody speaks of evil, it has to be in the context of an almighty and perfect God?

A: On the first question, you are clearer than I was. I accept your correction. On the second question, I am clearer than you were, and I hope you accept my correction. First of all, I have been talking so much about suffering that I virtually identified it with evil, and that is a mistake. There is the evil that you do, and there is the evil that you suffer. The evil that you do is much worse.

The evil that you do is, broadly speaking, sin. That is evil to your self, your character, your soul. Suffering is just evil to your body; that is the distinction Socrates played on when he said, “No evil can happen to a good man.” But on the other question, evil is not an opinion. Evil is not a point of view; evil is not psychological perspective. Evil is real; it is not a thing, but it is real. We can make mistakes about it. We argue about it. The fact that everybody argues about good and evil— “That’s good.” “No, it is evil”— means that we act as if we believe that evil is objectively real and not just a matter of opinion. We don’t argue about mere opinions. We can, but not really. I love the Red Sox; you love the Yankees. We don’t argue about that. We argue about facts. Will the Red Sox ever win a single World Series until the end of the world? We who are wise know the answer is “No, they’re under a curse.” Those who are not wise might say, “Yes.”

So, what is true and false has to have reference to an objective truth. But a mere opinion or point of view is not just true and false. Evil is not just a point of view; evil is not subjective. If you believe that evil is a subjective point of view, well, I don’t think most New Yorkers believe that anymore after 9/11. In the babble of voices that we heard after that horrendous event, one voice was conspicuously silent: psychobabble.

Q: I want to come at you from a ruthlessly pragmatic angle, being a New Yorker.

A: Wonderful.

Q: Pascal’s bet works for me, except— and this is something Pascal addressed— he said that living by faith will not damage your life; you will live a better life. You will practice the virtues, and in the end you will have a happier life. Therefore, it is not really such a risk. But what about Ignatius and his three degrees of humility? The first degree is the willingness to renounce mortal sin for the sake of salvation. The second one is an indifference toward suffering and having a happy life or sad life, long life or short life, so long as you are doing the will of God. I am getting queasy here. The third level of humility is to actively prefer a short, unhappy life because it is more similar to Jesus’s life on earth. Now, it seems to me that if your faith actually entails the third degree of humility, Pascal’s bet ceases to make sense. This is something that has been vexing me for years so I would really appreciate your response.

A: I think Pascal would say that the bet still works in the long run, even if you are up to this third level. That means that in the long run, that is, in heaven, you will have more joy. You have hollowed out your soul by these ascetic exercises so much that you can see, appreciate, and enjoy more of God than others can. So, it is worth it, even in the long run.

Q: It is worth it even on earth?

A: Yes, even on earth, because the saints are terribly happy. The two groups of people that haunt my memory and stand out as incredibly happy, truly happy, deeply happy, are the two most ascetical groups that I know. One is a group of Carmelite nuns in Danvers, Massachusetts, who live in almost perpetual silence. I was asked to give a talk to them; they gave a talk to me by their silence. And most of all, Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity. They have a house in Roxbury, which is the worst slum of Boston, and they pick up the pieces of the worst neighborhood, with the worst families, and they just do what they can. I was asked to give a talk to them, and they were just radiantly happy. They get up at four a.m., they each have one piece of clothing and almost no private property, and they eat very simply. They are radiantly happy. It works.

Q: I have a question I would like to limit to evil, rather than suffering. You mentioned that in the Bible, God doesn’t give us a reason for the existence of evil. He didn’t give Job a reason; he doesn’t give us a reason for his reason. In your tremendous study and the amount of thought that you have put toward the subject, have you personally found an answer for this, and if so, where? And if not, does that lead you somewhere else?

A: Let me just give you a partial answer to that question. As a philosopher, I was always bothered by the book of Job. I knew it was a classic— I felt it was a classic— but I was bothered by the fact that God didn’t answer any of Job’s questions. I said, “Yes, God has the right to do that, but I don’t like that.” Job cops out too easily: “Yes, God, anything you say.” I don’t like slimy, pious worms who say, “Okay, anything, step on me.” I guess I’m too much of a New Yorker, and Job is such a New Yorker— until the end. He shakes his fist in God’s face and says, “You bloody butcher, how can you get away with this? I demand some explanations.” That is kind of impious maybe, but we can identify with that. Then, at the end, what a disappointment— all of these great questions are not answered.

So, I said that is a failure of dramatic art. The character of Job changes too quickly in the end. The author of the book of Job, I thought, did to Job what Peter Jackson, the director of the movie, did to Faramir in The Two Towers— which is inexcusable.

(#ulink_c173eaba-ebb3-54a4-9dd7-28d838ef5cef) He is a hero, not a villain. However, reading Martin Buber— I think it was I and Thou— convinced me that I was utterly wrong. Buber is commenting on God’s pronouncement of judgment at the end of Job; the three friends of Job, who are perfectly orthodox theologians, say, in tedious repetition, “God is great and God is good, let us thank him for our food. Amen.” They utter no heresy, yet they are condemned.

Job, on the other hand, who flirts with heresy and blasphemy— “God, you are an arbitrary despot. I hate you. Get off my back”— is approved. God says— I think the words are “I am angry at you and your three friends. . . .” He blames “Bildad the Shuhite,” the smallest man in the Bible, “for not speaking rightly about me, as my servant Job has.” But they had spoken perfectly rightly about God, and Job had spoken wrongly.

“Wrong,” says Buber. Since God is the Thou who can only be addressed and not expressed and since God’s divinely revealed name is I Am, not It Is, therefore, Job, who talks to God, pleases God, unlike the three friends, who never talk to God, never pray, and never talk about him and thus do not please God.

I said, “That’s right.” Suppose I was teaching a class, and two of my students interrupted my lecture by breaking out into loud, animated conversation about the professor: “Do you think Professor Kreeft is crazy?” “No.” “Yes, he is.” “No, he isn’t.”

“Wait a minute!” I would say. “Hello, I’m here.” I wouldn’t be offended that they thought I was crazy. That is quite reasonable, but not that you would talk about me in front of me without realizing that I’m here. Well, that’s what we’re doing to God all the time.

“God this, God that.” “Hi, troops, I am here. Why aren’t you talking to me?” Talking— that’s what Job did. That’s what God wants. I think that is very profound.

Q: Are you saying that you think evil exists or possibly exists so that we will pay better attention to God, so that we will engage God?

A: We are such fools that I have to admit that’s true. C. S. Lewis puts it this way in The Problem of Pain: “God whispers to us in our pleasures, but shouts to us in our pains.” It is this megaphone that rouses a deaf world.

Q: If you accept a theistic framework, is asking, “Why?” tantamount to a lack of trust in God’s sovereignty?

A: Just the opposite.

Q: To make it practical, to give an example, one that I have wrestled with, is Eric Liddell. Eric Liddell, as you know from Chariots of Fire, ran and won the Olympic gold, and then what most people forget is that afterward, he left and went to Shantung Compound, which is the title of another great book by Gilkey. He suffered and died there. So, overlaying your framework of suffering on top of that, is all we are left with that God will have a greater purpose or is there another answer to that question?

A: If you weren’t deeply connected with God, you wouldn’t be asking him, “Why?” If you had left him, there would be no concern. The question “Why?” if asked from the heart, presupposes a relationship. It wants to add reason to faith. There is some faith there— faith, not just as thought but as personal trust. Then, that faith is ignorant. Since it is accompanied by love, it wants to know more. We want to know more about him; so we keep asking God, “Why this and why that?” That is very good. Jesus never once discouraged that kind of question. That is just intellectual honesty.

Q: Coming from the seat of Northern philosophy in Boston, can you give us New Yorkers, who experienced 9/11, some philosophical reference and reflection?

A: Can you be more specific so that I can be?

Q: Many people have lost a chance of hope. Many people have found a chance of hope, and many are still looking for that chance of hope.

A: I think great good and great evil, great pleasure and great pain, always give us a choice. We can be more wise and hopeful and good in the presence of either one, or we can be less. Let’s first take great good. A wonderful thing happens, and we can say, “Oh, now I can relax; everything is all right; no more questions.” No, no, no, a wonderful thing happens: “Where did this come from? Thanks be to God. Wow. This is a message from heaven.” It is a pointing finger that points beyond itself.

Similarly with evil. Evil just happens. I have a picture on my office wall; maybe some of you have seen it. It’s about something that happened, I think, toward the end of the nineteenth century in Paris. There is a two-story railroad station, and a locomotive plunged through the second story and fell down into the street, and there it is at an angle. A great, big steam locomotive and a single word on it— shit. That is not blasphemous; it is only obscene. It is an offense against good taste but not against good religion. That is one answer to evil, and that is counterproductive. It doesn’t do any good. But, on the other hand, what happened on 9/11 is evil. It shows me that evil is real. I am now wise. It shows me that I must have solidarity with my brothers and sisters in fighting it. So, I become more courageous.

The response in uniting New York and America, and even the world, certainly did an enormous amount of good. I won’t say it did more good than the thousands of lives that were snuffed out, but evil always rebounds. Evil always has some good fruit. I think of God as something like a French chef who uses decayed vegetables to flavor foods wonderfully. The evil always has some good purpose.

Q: I have a question about evil and suffering and the difficulty of taking a perspective on it in a culture that’s gripped with fear— which I see America as being at present. Do you think that could at all skew a perspective that you might take on evil and suffering? In other words, to the extent that you might even gather together in a really nice place like this and start talking about it as if it were something definitely real, as opposed to what somebody else might say it has been. The undercurrent of what I am asking is, is there a concern that there is an exclusion of a nontheistic perspective, of a nonphilosophical perspective? A perspective that takes into account psychological data, which I noticed you kind of pooh-poohed.

A: Not data; don’t fault the data. The theories.

Q: There is a lot of data and support of the contention that reminders of mortality actually lead to strengthening of bonding to cultural worldviews, for instance. So, do you think that there is some degree of relativity, and do you think that your view is colored by your worldview and your biases and perhaps even by your own development?

A: Of course it is.

Q: I am just wondering if you see how that colors your perspective on suffering.

A: That’s what a worldview is. A worldview isn’t a factual detail. It’s a picture of the whole. It’s a map that puts the details in a certain order, and everybody has one. Nobody can avoid one, even those who oppose worldviews. That is itself a worldview.

Q: So, how does that affect your perspective on suffering and evil?

A: It gives me light. It’s a flashlight. The data are the same. You and I both know the data. We interpret the why. There are two different reasons why two different people interpret the same data very differently.

One of them comes from the person— your character, your personality, your proclivities, your fears, your desires, your opinions. The other might come from objective truth. There might be a light that shines in one mind and not the other. Or, more likely, a light that shines in both minds, but differently, so that you see something that is really there that I don’t, and I see something that is really there and you don’t.

For instance, let’s say that I, as a typical theist, would say, “Death is great, because it leads to heaven.” I am omitting a whole lot. Death is an atrocity. Death is an enemy before it is a friend. It can be a friend, even if there is no life after death, because life on earth forever without death would be like eggs going rotten. I might not see that as someone who doesn’t believe in life after death does see it. So, since I am sensitive to that data, I have to listen more to you.

Q: So, you are still looking at forever; maybe there is just forever.

A: Yes. We all have to be open to all the data we can, but it seems to me that we have to be looking for truth, not just comparing opinions. Comparing opinions is just sort of internal mental masturbation— playing with opinions.

Q: Maybe it’s all we have.

A: If that is all we have, then we are like those two people in the New Yorker cartoon some years ago on a desert island, starving. A message in the bottle comes. There is hope. They open the message, they read it, and their faces fall. The caption says, “It’s only from us.”

Q: It may be Harvey; it may be Harvey.

A: Well, if it is Harvey, we are in for it, but at least you can still make a Pascal’s wager. There is no conclusive case that it is only Harvey. So, if both options are equally intellectually respectable, what would you gain by the despair and the emptiness by opting for it? At least Pascal’s wager makes sense, doesn’t it?

Q: I don’t look at things only in terms of loss and gain.

A: No, neither do I. That comes second. The most important question is truth. If you would give me a tremendous psychological gain, an immense amount of happiness at the expense of truth or an immense amount of truth at the expense of happiness, that would be a hard choice. But I would, at least, want to choose truth, rather than happiness.

William James divided all minds into the tender-minded and the tough-minded. The tender-minded seek happiness and ideals and comfort and integration and all that sort of thing. The tough-minded seek facts. He said that a tough-minded person and a tender-minded person can’t understand each other and can’t really have an argument. I think he’s a little wrong there, because deep down, I think we’re all tough-minded. For instance, this is a wonderful place, but does anybody really think this is heaven and that I’m God? If you thought that this was heaven and I was God and this was the beatific vision, would you be happy? If happiness is all you want, why would you believe that, because we know that it is not true, stupid. See, truth trumps happiness. So, one, truth; two, happiness.