По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

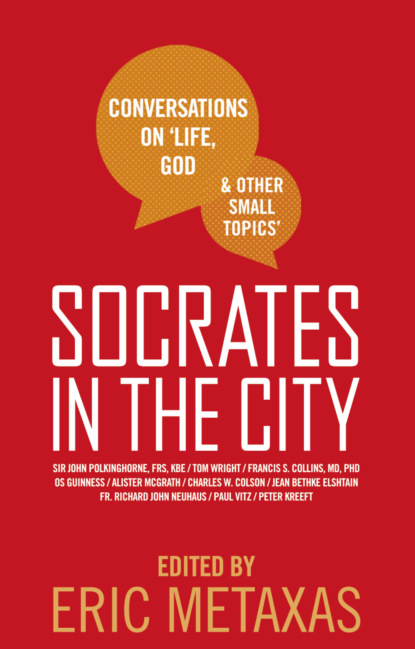

Socrates in the City: Conversations on Life, God and Other Small Topics

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Q: Romans 8:28 promises that God will work “all things together” for the good. It would seem that he is saying that for believers, for those who love him and “are called according to his purpose.” How should we regard suffering in the lives of people who are ostensibly good people by the world’s standards but who are not believers?

A: I don’t know, because we don’t know who are the chosen and who are not. I don’t think we can make that judgment. We don’t have the faintest idea. Relatively, when the disciples ask Jesus, “Are many saved?” he says, “Strive to enter in. Mind your own business.” So, we’re told about our path. We’re not told about anyone else’s. When the travel agent tells you how to get to Florida, she doesn’t tell you how to avoid the swamps in Georgia; she tells you how to go to the beaches.

Q: I don’t mean to imply that we necessarily know who are saved or who are not, but we do know that there are some who are not saved. How should we regard suffering in their lives?

A: I don’t think we have any data about that. I don’t have an answer. We haven’t been told, as far as I know. We have been told the astonishing thing that for those who love God, all things work together for good. Now, that is hard to believe. I love Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey about a Franciscan priest, Brother Juniper, who is losing his faith. He is a scientist, and he asks God for some clues, just some clues. “Life is a mysterious tapestry,” he says. “I don’t expect to see the front side where God is weaving it, but some loose threads on the back side, they should make at least some sense.”

One day he reads in a paper that a rope bridge over this gorge has parted and five young people have fallen to their untimely deaths, and he is scandalized. He says this makes no sense at all; so, he makes a scientific investigation of their lives. He interviews family members and reads diaries and collects clues, and the result of the investigation is, he thinks, he gets just enough clues to believe; so, he concludes with a memorable sentence: “Some say that to the gods we are like flies swatted idly by boys on a summer’s day; others say that not a single hair ever falls from the head to the ground without the will of the heavenly father.” Both are possible choices.

Q: Is it possible to be happy without having ever suffered? Or are happiness and suffering mutually exclusive?

A: How can you be really happy if you’ve never suffered? You are a spoiled kid; you appreciate nothing. We appreciate things only by contrast. I just came from Hawaii. There was an international conference on arts and humanity. I thought it was a real conference; there were 1,687 people who went to that conference. They all delivered papers to about two or three people, and universities paid their way. It was just a scam to get to Hawaii. I’m a surfer; Hawaii is Mecca to me. But I didn’t really deep down enjoy myself. Why not?

I guess because I am a New England, puritanical, Calvinistic Red Sox fan; there is no suffering out there. Things are so perfect. I couldn’t live there. I would not appreciate the summer without the winter. You have to live through this kind of winter to appreciate the summer. And if we never died, we wouldn’t appreciate life.

There’s a fascinating book written about twenty years ago called The Immortality Factor by a Swedish journalist Osborn Segerberg Jr. He first interviewed geneticists about whether artificial immortality was theoretically possible, and most of them said, “Yes,” and that it will come in two hundred to three hundred years. Most scientific predictions, by the way, are much too long. It will probably come much earlier than that. That’s another story. Then he looked at the old myths about immortality and the science fiction stories. Both the old myths and the modern science fiction stories— such as the myth of Thesonius the Greek or the Wandering Jew or the Flying Dutchman or the book Tuck Everlasting or Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke— almost all said this would be horrible, the worst thing conceivable. Without death, life becomes meaningless.

Then, Segerberg went to the psychologists and asked what would happen. Most of them said, “Oh, this would be wonderful— the end of suffering, the end of fear. We would have utopia on earth.” He concluded that the myths were perhaps wiser than the psychologists. So, I guess we need suffering, because we’re very stupid, and if you’re very stupid, you have to have your nose rubbed in something, since you will appreciate something only by its contrast. I’m continually impressed by how stupid I am.

One of the most unpopular doctrines of Christianity is the doctrine of Original Sin. I have no difficulty at all believing that, because I know from my own experience that whenever I sin, I suffer, but I keep sinning. I wake up in the morning, and I get assaulted by a thousand little soldiers sticking pins into my brain and saying, “Think about this, think about this; worry about this, worry about this.” If I kill them ruthlessly and give God a little bit of time in the morning, I’m happy, and everything happens well in the day. And if I don’t, it doesn’t. If I don’t do it, I’m insane! We all are. So, we need to be slapped around a bit, I guess.

Q: I would love to hear your thoughts on reconciliation and the idea of suffering in the mind of somebody who believes he or she is unforgiven as the cause of suffering.

A: You would have to address their problem, which is the belief that there is something that is unforgiven. If God is totally good, he is not Scrooge. He does not forgive some things; he forgives all things. The only possible sin that cannot be forgiven is not accepting forgiveness, which is why in traditional Christian theology, pride is the worst of sins: “I am too good to be forgiven; there is nothing to forgive.”

Q: Follow-up question: I mean unforgiven by another person, who has caused suffering.

A: Oh, that is a very serious problem. Yes, I suppose the only refuge there would be is the belief that since God forgives them, they have to forgive themselves. In other words, it can’t be just a horizontal thing, because that is blocked very often. But if both the horizontal members are connected vertically, then in a way that I don’t think we usually understand, there can be a reconciliation that we don’t usually see. That is rather mystical, I guess. I think that works even in time. Since God is eternal, he can change the past. But we can’t see that, because we are in time.

Q: You mentioned Aquinas, and, as I recall, he was a very practical Aristotelian type of thinker. How would you compare his views that you gave tonight with Augustine, who always appeared to be more Socratic? How would you compare their two views on faith, hope, and love, and, in particular, on suffering?

A: In his encyclical Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), Pope John Paul II speaks of faith and reason as the two wings of the dove— the human soul. I would say that within the intellect, Augustine and Aquinas are the two wings. Augustine is a wonderfully passionate thinker. There is nothing like The Confessions— a heart and a mind working at fever pitch together. I love the medieval statuary of Augustine. It always shows him with an open book in one hand and a burning heart in the other.

Aquinas, on the other hand, is a perfectly clear light, a perfect scientist. Augustine, you might say, is a mole burrowing through the deep mysteries, whereas Aquinas is the eagle soaring over it all, making a map. Together, they give you a great picture. Aquinas’s answer to that problem that he formulates, by the way, is wonderfully Augustinian in the sense that it is dramatic. It is not just an abstract philosophical concept. The problem is, how can there be God if there is evil? If one of two contraries is infinite, the other is destroyed. God is infinite goodness; if there were God, there would be no evil. There is evil; so, therefore, there is no God.

His answer— and he gets it from Augustine, who says that God would not allow any evil; God doesn’t do it, but he allows it through human free will. God would not allow any evil, unless his wisdom and power were such as to bring out of it an even greater good. The fairy-tale answer. We are not yet in the happily-ever-after; we are struggling toward it.

Q: I think that one of the most difficult problems that many of us have in dealing with the problems of suffering is not how we deal with them individually, but how other people deal with suffering, as we perceive it. At the end of the movie that is now certainly drawing an awful lot of comment, The Hours, one of the lead characters describes her choice that has to do with leaving her children with a very familiar phrase. Of course, in the movie you never really understand that she’s having a problem with this child; it’s revealed only at the end. The movie is about suicide, if you haven’t seen it. That is not the ending, which is much more dramatic; this is just a piece of it.

She says, “I chose to leave because I chose life.” Now, that is not ordinarily the application of that phrase— that a mother would leave her children in order to choose life. There really is a whole lot more to the film, if you haven’t seen it. I was just absolutely struck by the application of that phrase to what, to me, on the surface of it would be someone struggling to overcome evil as a very bad choice.

A: I think it’s a fake. I haven’t seen the movie, but her mistake is that she is thinking only about her own life. Life is like a tree, and it has many branches, many leaves, many roots. It is one. The idea of human solidarity, both in sin and in suffering, is rather hard for us uprooted, overly self-conscious individualists to understand, but almost any ancient people understood it better than we do. You can’t really be happy and fulfilled and alive without those to whom you are deeply connected being the same.

Q: I see you wrote a book on Socrates and Jesus. In First Corinthians, the Apostle Paul says, “We preach Christ crucified . . . foolishness to the Gentiles.” Apparently, Paul had some experience of talking to the Greeks, and as he talked to them, they said, “You are a fool.” Now, what is it about Greek thinking that makes Paul a fool in their eyes?

A: Most people are fools. The percentage of non-fools is very small everywhere. I believe Paul wrote that epistle to the Corinthians after he had visited Athens. In Acts 17, he goes to Mars Hill, where Socrates actually philosophized, and addressed the philosophers. They said, “What is this strange saying?” Now he has the opportunity to talk to philosophers. Athens and Jerusalem are coming together.

I have never been to Athens, but I have been told that Mars Hill is at the top of a long road called “the Way of the Gods.” There were statues to all of the gods, not just Greek gods, but gods of many other cultures, because people would come to Athens from many places and make sacrifices to their many gods. Paul refers to them in the first part of his sermon to the Athenians, when he says that, as he was walking up this road, he noticed that they are “very religious.” That is sarcastic, because before that, he said that his heart burned within him, because of the idolatry. You would expect he is going to say something similar to what he had said to the Corinthians: “What fools you are.” Astonishingly, instead, he says, “But one of these inscriptions I noticed was dedicated to an unknown God.”

Socrates was, in fact, a stonecutter, and there were two kinds of stonema-sons in ancient Greece. One just cut altars and letters, which was easy. Then there were the sculptors who had to do rounded human figures, and not too many people could do that. If you could do that, you got rich, but Socrates was very poor. So, Socrates cut things like altarpieces and inscriptions. As you know, if you read any of Socrates, you know that he worshipped the unknown God. He would not name this God, and he lost his life, because he couldn’t name him Zeus or Apollo or any of the gods of the state. So, it may be that Socrates literally cut this very altarpiece that Paul refers to: To the unknown God.

What does Paul say about it? “The God that you are already worshipping ignorantly, I will now declare to you.” I think that’s the other side of the foolishness. Yes, there is Greek foolishness. Socrates is not a fool, because he knows that he is a fool. He will not name the God he knows he doesn’t know. He is searching— and according to rather high authority, those who seek find. I would be very surprised not to find Socrates in heaven.

Q: I think that the apostle Paul ends First Corinthians, chapter 1, by saying, “of him we are in Christ Jesus,” that is, it is God’s choice who goes to heaven.

A: And it is also ours; it is not exclusive.

Q: That is true.

A: That is a paradox of predestination and free will, both of which are very clearly taught. That is the paradox of every great novel. Show me one novel without predestination by the author; show me one novel without free will by the characters.

Q: Well, I don’t understand. It seems to me that you are involved in a self-contradiction. On the one hand, you are saying that Socrates is in heaven. On the other hand, the apostle Paul says that the debaters of this age did not know God. Now, are you saying that people who do not know God are going to heaven?

A: No, but I don’t think Socrates is one of those people. I don’t think he was a mere debater. He was a seeker.

Q: Paul does say the Greeks have called him a fool.

A:The Greeks is a vague term, like the Jews. To stereotype a whole people or a whole race is silly.

Q: I guess to make it a long story short, I would think you would have to introduce the question of regeneration.

A: Yes, but my very conservative and traditional belief that Jesus is not just a human being but the Logos, the eternal second person of the Trinity, justifies my rather liberal expectation that a lot of non-Christians will be in heaven. That is because John says in his gospel, chapter 1, verse 9, the Logos enlightens everyone who comes into the world. So, even though Jesus is the universal savior, you don’t have to know him in his thirty-three-year-old, six-foot-high, Jewish-carpenter body. There are other ways to know him, and maybe Socrates did.

Q: I wish I could agree with you, but I don’t.

A: All right, some other day.

Q: My question has to do with the nature of God. The Scripture said, “Jacob I loved, and Esau I hated.” How do you defend to someone how a good and loving God can hate?

A: I don’t know Hebrew, but I would bet on the fact that the word hate there means the same thing that the Greek word for hate means in one of Jesus’s strange sayings: “Unless you hate your father and your mother, you cannot be my disciple.” Hate means “turn your back on, when necessary”— put second, rather than first.

So, it’s not that God was burning with hatred for Esau, because Esau didn’t exist yet. This is talking about predestination. Before they were even born, God said, “Esau is going to be the villain; Jacob is going to be the hero,” like a novelist. That doesn’t mean they don’t have free will. The novelist gives them the free will to choose heroism or villainy, but he knows what they’re going to choose.

Q: First of all, thank you for sharing your wisdom with us. Once, in a philosophy class, I heard the statement that evil is not part of creation but is the absence of good or goodness. I was wondering, first of all, if you could expand on that, and secondly, could you give me some background on where it originated, stated in that concrete manner?

A: That is probably referring to a great discovery Augustine made. He talks about it in The Confessions. He couldn’t solve the problem of evil, so he became a Manichean for eleven years. The Manicheans believed that evil; is explained by the fact that there is an evil God and a good God and that they are equal and fighting and nobody is winning forever. The evil God made matter, and the good God wants to liberate you from matter into spirituality.

Augustine never felt right about Manicheism. He was always looking for a better answer, and he finally got one— the realization that since God is totally good and that since everything that exists and is made of matter is a creature of God, therefore, all matter is good— Ens est bonum, “Being as such is good.”

Then, what is evil? Evil is not a thing; it is not stuff. It is neither God nor creature. It is not a being in that sense; it is nonbeing, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. It doesn’t mean that it is not real. Blindness is not a third eye, and blindness is not a cataract that causes it. Blindness is the absence of a good thing— sight. Not just absence but privation. This microphone doesn’t have sight, but that is not evil for it; it’s not supposed to. But a person’s eye is supposed to have it. So, the privation of good being in something that it is supposed to have is the answer to “What kind of stuff does evil have?” and “What is the metaphysics of evil— the being of evil?” That is the answer to an abstract question. It is not the answer to a concrete question, such as “Is evil real for me?” And “How does it appear in my life?” is a different question entirely. So, it is very important to keep those two unconfused. Otherwise, Augustine sounds like a cockeyed optimist: “Oh, evil isn’t real; don’t worry about it.” He was deeply sensitive to it.

Q: My question is in two parts. The first one is this. James said, “[C]ount it all joy when you [fall into] divers temptation, knowing [this], that the trying of your faith worketh patience” [James 1:2–3, King James Version]. How do we look at and rationalize every attempt by man to eliminate human suffering, knowing that suffering is part of what life is all about? The second part of the question is this: Since we know that suffering is not something that man actually created in himself, should we believe that, instead of helplessness, the Lord is trying to alleviate these problems?

A: The practical answer to that question is very clear. Certainly, if you’re a Christian, you believe that Jesus healed people from diseases and sufferings. He had great compassion and pity on suffering. He was completely human and showed us not just who God was but who the ideal man was. So, the Stoic attitude of indifference to suffering or the withdrawn attitude or even the Buddhist attitude of rising above it by being insensitive to it by transforming your consciousness, that is definitely not the Christian answer to suffering.

But your first question is a deep paradox. On the one hand, suffering is blessed. Count it as a joy when you go through manifold tribulations. On the other hand, we are supposed to relieve it— like poverty. Blessed are the poor— and yet the relief of poverty is one of the commandments of Christianity. Death, which is the fishnet that catches all the fish of poverty and every other suffering in itself, is the worst thing. It is the last enemy. Jesus comes to conquer it through resurrection.

On the other hand, death is glorious. There is an old oratorio that has this hauntingly beautiful line: “Thou hast made death glorious and triumphant, for through its portals we enter into the presence of the living God.” Somehow or other, in this strange drama, the worst things are used as the best things. Even morally, the worst sin ever committed, the most horrible atrocity ever perpetrated in the history of the world, was the murder of God’s Son, and Christians celebrate this as Good Friday and the cause of their salvation. It is very strange— like life.