По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

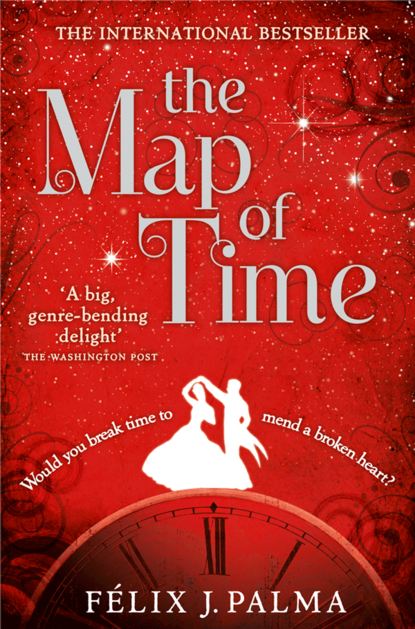

The Map of Time

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Andrew promised he would go, tossing the remains of his apple on to the table.

‘Anyway’ Charles concluded rather wearily, ‘the poor wretches in Whitechapel have formed vigilante groups and are patrolling the streets. It seems London’s population is growing so fast the police force can no longer cope. Everybody wants to live in this accursed city. People come here from all over the country in search of a better life, only to end up being exploited in factories, contracting typhus fever or turning to crime in order to pay an inflated rent for a cellar or some other airless hole. Actually, I’m amazed there aren’t more murders and robberies, considering how many go unpunished. Mark my words, Andrew, if the criminals became organised, London would be theirs. It’s hardly surprising Queen Victoria fears a popular uprising – a revolution like the one our French neighbours endured, which would end with her and her family’s heads on the block. Her empire is a hollow façade that needs progressively shoring up to stop it collapsing. Our cows and sheep graze on Argentinian pastures, our tea is grown in China and India, our gold comes from South Africa and Australia, and the wine we drink from France and Spain. Tell me, cousin, what, apart from crime, do we produce ourselves? If the criminal elements planned a proper rebellion they could take over the country. Fortunately, evil and common sense rarely go hand in hand.’

Andrew liked listening to Charles ramble in this relaxed way, pretending not to take himself seriously. He admired his cousin’s contradictory spirit, which reminded him of a house divided into endless chambers all separate from one another, so that what went on in one had no repercussions in the others. This explained why his cousin was able to glimpse, amid his luxurious surroundings, the most suppurating wounds and forget them a moment later, while he found it impossible to copulate successfully after a visit to a slaughterhouse or a hospital for the severely injured. It was as if Andrew had been designed like a seashell: everything disappeared and resonated inside him. That was the basic difference between them: Charles reasoned and he felt.

‘The truth is, these sordid crimes are turning Whitechapel into a place where you wouldn’t want to spend the night,’ Charles declared sententiously, abandoning his nonchalance to lean across the table and stare meaningfully at his cousin. ‘Especially with a tart’

Andrew gaped at him. ‘You know about it?’

His cousin smiled. ‘Servants talk, Andrew. You ought to know by now our most intimate secrets circulate like underground streams beneath the luxurious ground we walk on,’ he said, stamping his feet symbolically on the carpet.

Andrew sighed. His cousin had not left the newspaper there by accident. In fact, he had probably not even been asleep. Charles enjoyed this kind of game. It was easy to imagine him hiding behind one of the many screens that partitioned the vast dining room, waiting patiently for his stunned cousin to fall into the trap he had laid.

‘I don’t want my father to find out, Charles,’ begged Andrew.

‘Don’t worry, cousin. I’m aware of the scandal it would cause in the family. But tell me, are you in love with the girl or is this just a passing fancy?’

Andrew remained silent. What could he say?

You needn’t reply’ his cousin said, in a resigned voice. ‘I’m afraid I wouldn’t understand either way. I only hope you know what you’re doing.’

Andrew, of course, did not know what he was doing, but could not stop doing it. Each night, like a moth drawn to the flame, he returned to the miserable room in Miller’s Court, hurling himself into the relentless blaze of Marie Kelly’s passion. They made love all night, driven by frantic desire, as though they had been poisoned during dinner and did not know how long they had left to live, or as though the world around them were being decimated by the plague. Soon Andrew understood that if he left enough coins on her bedside table, their passion could continue gently smouldering beyond the dawn. His money preserved their fantasy, and even banished Joe, Marie Kelly’s husband, whom Andrew tried not to think of when, disguised in his modest clothes, he strolled with her through the maze of muddy streets.

Those were peaceful, pleasant walks, full of encounters with the girl’s friends and acquaintances, the long-suffering foot-soldiers of a war without trenches; a bunch of poor souls who rose from their beds each morning to face a hostile world, driven on by the sheer animal instinct for survival. Fascinated, Andrew found himself admiring them, as he would a species of exotic flower alien to his world. He became convinced that life in Whitechapel was more real, simpler, easier to understand than it was in the luxuriously carpeted mansions where he spent his days.

Occasionally, he had to pull his cap down over his eyes in order not to be recognised by the bands of wealthy young men who laid siege to the neighbourhood some nights. They arrived in luxurious carriages and mobbed the streets, like rude, arrogant conquistadors, in search of some miserable brothel where they could satisfy their basest instincts for, according to a rumour Andrew had frequently heard in West End smoking clubs, the only limits on what could be done with the wretched Whitechapel tarts were money and imagination. Watching these boisterous incursions, Andrew was assailed by a sudden protective instinct, which could only mean he had unconsciously begun to see Whitechapel as a place he should perhaps watch over. However, there was little he could do, confronted with those barbarous invasions, besides feeling sad and helpless, and trying to forget about them in the arms of his beloved. She appeared more beautiful to him by the day, as though beneath his caresses she had recovered the innate sparkle of which life had robbed her.

But, as everyone knows, no paradise is complete without a serpent, and the sweeter the moments spent with his beloved, the more bitter the taste in Andrew’s mouth when he recalled that what he had of Marie Kelly was all he could ever have. Because, although it was never enough and each day he yearned for more, the love that could not exist outside Whitechapel, for all its undeniable intensity, remained arbitrary and illusory. And while outside a crazed mob tried to lynch the Jewish cobbler nicknamed Leather Apron, Andrew quenched his anger and fear in Marie Kelly’s body.

He wondered whether his beloved’s fervour sprang from her own realisation that they had embarked upon a reckless love affair, and that all they could do was greedily clasp the unexpected rose of happiness as they tried to ignore the painful thorns. Or was it her way of telling him she was prepared to rescue their apparently doomed love even if it meant altering the very course of the universe? And if that was the case, did he possess the same strength? Did he have the necessary conviction to embark upon what he already considered a lost battle?

However hard he tried, Andrew could not imagine Marie Kelly moving in his world of refined young ladies, whose sole purpose in life was to display their fecundity by filling their houses with children, and to entertain their spouses’ friends with their pianistic accomplishment. Would Marie Kelly succeed in fulfilling this role while trying to stay afloat amid the waves of social rejection that would doubtless seek to drown her, or would she perish like an exotic bloom removed from its hothouse?

The newspapers’ continued coverage of the whores’ murders scarcely managed to distract Andrew from the torment of his secret fears. One morning, while breakfasting, he came across a reproduction of a letter the murderer had audaciously sent to the Central News Agency, assuring the police they would not catch him easily and promising he would carry on killing, testing his fine blade on the Whitechapel tarts. Appropriately enough, the letter was written in red ink and signed ‘Jack the Ripper’, a name that, however you looked at it, Andrew thought, was far more disturbing and imaginative than the rather dull ‘Whitechapel Murderer’ by which he had been known until then.

The new name was taken up by all the newspapers, and inevitably conjured up the villain of the penny dreadfuls, Jack Lightfoot, and his treatment of women. It was rapidly adopted by everyone, as Andrew soon discovered from hearing it uttered everywhere he went. The words were always spoken with sinister excitement, as though for the sad souls of Whitechapel there was something thrilling and even fashionable about a ruthless murderer stalking the neighbourhood with a razor-sharp knife. Furthermore, as a result of this disturbing missive, Scotland Yard was deluged with similar correspondence (in which the alleged killer mocked the police, boasted childishly about his crimes and promised more murders). Andrew had the impression that England was teeming with people desperate to bring excitement into their lives by pretending they were murderers, normal men whose souls were sullied by sadistic impulses and unhealthy desires that fortunately they would never act upon.

Besides hampering the police investigation, the letters also transformed the vulgar individual he had bumped into in Hanbury Street into a monstrous creature apparently destined to personify man’s most primitive fears. Perhaps this uncontrolled proliferation of would-be perpetrators of his macabre crimes prompted the real killer to surpass himself. On the night of 30 September, at the timber merchants’ in Dutfield Yard, he murdered Elizabeth Stride – the whore who had originally put Andrew on Marie’s trail – and a few hours later, in Mtre Square, Catherine Eddowes, whom he had time to rip open from pubis to sternum, remove her left kidney and even cut off her nose.

Thus began the cold month of October, in which a veil of gloomy resignation descended upon the inhabitants of Whitechapel who, despite Scotland Yard’s efforts, felt more than ever abandoned to their fate. There was a look of helplessness in the whores’ eyes, but also a strange acceptance of their dreadful lot. Life became a long and anxious wait, during which Andrew held Marie Kelly’s trembling body tightly in his arms and whispered to her that she need not worry, provided she stayed away from the Ripper’s hunting ground, the area of backyards and deserted alleyways where he roamed with his thirsty blade, until the police managed to catch him.

But his words did nothing to calm a shaken Marie, who had even begun sheltering other whores in her tiny room at Miller’s Court to keep them off the unsafe streets. It resulted in her having a fight with her husband, Joe, during which he broke a window. The following night, Andrew gave her the money to fix the glass and keep out the piercing cold. However, she simply placed it on her bedside table and lay back dutifully on the bed so that he could take her. Now though all she offered him was a body, a dying flame, and the grief-stricken despair she had been unable to keep from her eyes in recent days, a look in which he thought he glimpsed a desperate cry for help, a silent appeal to him to take her away before it was too late.

Andrew made the mistake of pretending not to notice her distress, as though he had forgotten that everything could be expressed in a look. He felt incapable of altering the very course of the universe, which for him translated into the even more momentous feat of confronting his father. Perhaps that was why, as a silent rebuke for his cowardice, she began to go out looking for clients and spending the nights getting drunk with her fellow whores in the Britannia. There they cursed the uselessness of the police and the power of the monster from hell who continued to mock them, most recently by sending George Lusk, socialist firebrand and self-proclaimed president of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, a cardboard box containing a human kidney.

Frustrated by his lack of courage, Andrew watched her return drunk each night to the little room. Then, before she could collapse on the floor or curl up like a dog beside the warm hearth, he would take her in his arms and put her to bed, grateful that no knife had stopped her in her tracks. But he knew she could not keep exposing herself to danger in this way, even if the murderer had not struck for several weeks and more than eighty policemen were patrolling the neighbourhood. He also knew he was the only one able to stop her. For that reason, sitting in the gloom while his beloved spun her drunken nightmares of corpses with their guts ripped out, Andrew would resolve to confront his father the very next day. But when the next day came all he could do was prowl around his father’s study, not daring to go in. And when it grew dark, his head bowed in shame, occasionally clutching a bottle, he returned to Marie Kelly’s little room, where she received him with her eyes’ silent reproach.

Then Andrew remembered all the things he had said to her, the impassioned declarations he had hoped would seal their union. How he had been trying to find her for he did not know how long -eighteen, a hundred, five hundred years – how he knew that if he had undergone reincarnations he had looked for her in every one, because they were twin spirits destined to meet each other in the labyrinth of time, and other such pronouncements. Now he was sure Marie Kelly could only see his avowals as a pathetic attempt to cloak his animal urges in romanticism or, worse, to conceal the thrill he derived from those voyeuristic forays into the wretched side of existence. ‘Where is your love now, Andrew?’ her eyes seemed to ask, before she trudged off to the Britannia, only to return a few hours later rolling drunk.

Until, on that cold night of 7 November, Andrew watched her leave again for the tavern, and something inside him shifted. Whether it was the alcohol, which, consumed in the right quantity, can clear some people’s heads, or simply that enough time had passed for this clarity to occur naturally, it finally dawned on him that without Marie Kelly his life would no longer have any meaning so he had nothing to lose by fighting for a future with her. Filled with resolve, suddenly able to breathe freely once more, he left the room, slamming the door resolutely, and strode off towards the place where Harold Barker waited while his master took his pleasure. The coachman was huddled like an owl on the seat, warming himself with a bottle of brandy.

That night his father was to discover his youngest son was in love with a whore.

Chapter V

Yes, I know that when I began this tale I promised there would be a fabulous time machine, and there will be. There will even be intrepid explorers and fierce native tribes – a must in any adventure story. But all in good time. Isn’t it necessary at the start of any game to place all the pieces on their respective squares? Of course it is – so let me continue to set up the board, slowly but surely, by returning to young Andrew, who might have taken the opportunity of the long journey back to the Harrington mansion to sober up, but who chose instead to cloud his thoughts further by finishing the bottle he had in his pocket.

Ultimately, there was no point in confronting his father with a sound argument and reasoned thinking: he was sure that any civilised discussion of the matter would be impossible. He needed to dull his senses as much as he could, staying just sober enough not to be completely tongue-tied. There was no point in slipping back into the elegant clothes he always left judiciously in a bundle on the carriage seat.

That night there was no longer any need for secrecy. When they arrived at the mansion, Andrew stepped out of the carriage, asked Harold to stay where he was, and hurried into the house. The coachman watched in dismay as he ran up the steps in his rags, and wondered if he would hear Mr Harrington’s shouts from where he sat.

Andrew had forgotten his father had a meeting with businessmen that night until he staggered into the library. A dozen men stood gaping at him in astonishment. This was not the situation he had anticipated, but he had too much alcohol in his blood to be put off. He searched for his father amid the array of dinner jackets, and finally found him by the fireplace, next to his brother Anthony. Glass in one hand, cigar in the other, both men looked him up and down. But his clothing was the least of it, as they would soon discover, thought Andrew, who in the end felt pleased to have an audience. Since he was about to stick his head in the noose, it was better to do so in front of witnesses than alone with his father in his study.

He cleared his throat loudly under the fixed gaze of the gathering, and said: ‘Father, I’ve come here to tell you I’m in love.’

His words were followed by a heavy silence, broken only by an embarrassed cough here and there.

‘Andrew, this is hardly a suitable moment to—’ his father began, visibly irritated, before Andrew silenced him with a sudden gesture of his hand.

‘I assure you, Father, this is as unsuitable a moment as any other,’ he said, trying to keep his balance so he would not have to finish his bravura performance flat on his face.

His father bridled, but remained silent.

Andrew took a deep breath. The moment had come for him to destroy his life. ‘And the woman who has stolen my heart,’ he declared, ‘is a Whitechapel whore by the name of Marie Kelly’

Having unburdened himself, he smiled defiantly at the gathering. Faces fell, heads were clutched in hands, arms flapped in the air, but no one said a word: they all knew they were witnessing a melodrama with two protagonists and, of course, that William Harrington must speak. All eyes were fixed on the host.

Staring at the pattern on the carpet, his father shook his head, let out a low, barely repressed growl, and put down his glass on the mantelpiece, as though it were suddenly encumbering him.

‘Contrary to what I’ve heard you maintain, gentlemen,’ Andrew went on, unaware of the rage stirring in his father’s breast, ‘whores aren’t whores because they want to be. I assure you that any one of them would choose to have a respectable job if they could. Believe me, I know what I’m saying.’ His father’s colleagues continued to demonstrate their ability to express surprise without opening their mouths. ‘I’ve spent a lot of time in their company, these past few weeks. I’ve watched them washing in horse-troughs in the mornings, seen them sitting down to sleep, held against the wall by a rope if they could not find a bed …’

The more he went on speaking in this way about prostitutes, the more Andrew realised his feelings for Marie Kelly were deeper than he had imagined. He gazed round with infinite pity at the men with their orderly lives, their dreary, passionless existences, who would consider it impractical to yield to a near-uncontrollable urge. He could tell them what it was like to lose one’s head, to burn up with feverish desire. He could tell them what the inside of love looked like, because he had split it open like a piece of fruit.

But Andrew could not tell them this or anything else because at that moment his father, emitting enraged grunts, strode unsteadily across the room, almost harpooning the carpet with his cane. Without warning, he struck his son hard across the face. Andrew staggered backwards, stunned by the blow. When he finally understood what had happened, he rubbed his stinging cheek, trying to put on the same smile of defiance. For a few moments that seemed like eternity to those present, father and son stared at one another in the middle of the room, until William Harrington said: ‘As of tonight I have only one son.’

Andrew tried not to show any emotion. ‘As you wish,’ he replied coldly. Then, to the guests, he made as if to bow. ‘Gentlemen, my apologies, I must leave this place for ever.’

With as much dignity as he could muster, Andrew turned on his heel and left the room. The cold night air had a calming effect on him. In the end, he thought, trying not to trip as he descended the steps, nothing that had happened had come as a surprise. His disgraced father had just disinherited him, in front of half of London’s wealthiest businessmen, giving them a first-hand display of his famous temper, unleashed against his offspring without the slightest compunction. Now Andrew had nothing, except his love for Marie Kelly. If before the disastrous encounter he had entertained the slightest hope that his father might give in, and even let him bring his beloved to the house, to remove her from the monster stalking Whitechapel, it was clear now that they must live by their own means. He climbed into the carriage and ordered Harold to return to Miller’s Court.

The coachman, who had been pacing round the vehicle in circles, waiting for the dénouement of the drama, clambered back onto the box and urged the horses on. He was trying to imagine what had taken place inside the house – and to his credit, based on the clues he had been perceptive enough to pick up, we must say that his reconstruction of the scene was remarkably accurate.

When the carriage stopped in the usual place, Andrew got out and hurried towards Dorset Street, anxious to embrace Marie Kelly and tell her how much he loved her. He had sacrificed everything for her. Still he had no regrets, only a vague uncertainly regarding the future. But they would manage. He was sure he could rely on Charles. His cousin would lend him enough money to rent a house in Vauxhall or Warwick Street, at least until they were able to find decent jobs that would allow them to fend for themselves. Marie Kelly could find work at a dressmaker’s – but what skills did he possess? It made no difference. He was young, able-bodied and willing. He would find something. The main thing was he had stood up to his father, and what happened next was neither here nor there. Marie Kelly had pleaded with him, silently, to take her away from Whitechapel, and that was what he intended to do, with or without anyone else’s help. They would leave that accursed neighbourhood, that outpost of hell.

Andrew glanced at his watch as he paused beneath the stone archway into Miller’s Court. It was five o’clock in the morning. Marie Kelly would probably have already returned to the room, probably as drunk as he. Andrew visualised them communicating through a haze of alcohol in gestures and grunts like Darwin’s primates. With boyish excitement, he walked into the yard where the flats stood. The door to number thirteen was closed. He banged on it a few times but got no reply. She must be asleep, but that would not be a problem. Careful not to cut himself on the shards of glass sticking out of the window frame, Andrew reached through the hole and flicked open the door catch, as he had seen Marie do after she had lost her key. ‘Marie, it’s me,’ he said, opening the door. ‘Andrew’

Allow me at this point to break off the story to warn you that what took place next is hard to relate, because the sensations Andrew experienced were apparently too numerous for a scene lasting only a few seconds. That is why I need you to take into account the elasticity of time, its ability to expand or contract like an accordion, regardless of clocks. I am sure this is something you will have experienced frequently in your own life, depending on which side of the bathroom door you have found yourself. In Andrew’s case, time expanded in his mind, creating an eternity of a few seconds. I am going to describe the scene from that perspective, and therefore ask you not to blame my inept story-telling for the discrepancies you will no doubt perceive between the events and their correlation in time.

When he first opened the door and stepped into the room, Andrew did not understand what he was seeing or, more precisely, he refused to accept what he was seeing. During that brief but endless moment, he still felt safe, although the certainty was forming in some still-functioning part of his brain that what he saw before him would kill him. Nobody could be faced with a thing like that and go on living, at least not completely. And what he saw before him, let’s be blunt about it, was Marie Kelly – but at the same time it wasn’t, for it was hard to accept that the object lying on the bed in the middle of all the blood was she.