По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

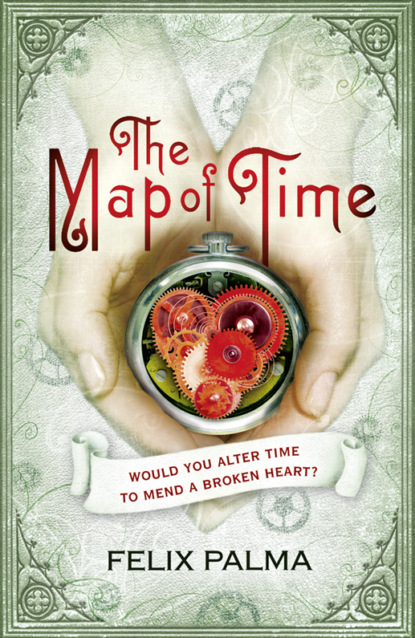

The Map of Time and The Turn of the Screw

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They came to a door at the far end of a long passageway.

‘Here we are,’ said Trêves, plunging for a few moments into a respectful silence. Then he looked Wells in the eye, and added, in a sombre, almost threatening tone: ‘Behind this door waits the most horrific-looking creature you have probably ever seen or will ever see; it is up to you whether you consider him a monster or an unfortunate wretch.’

Wells felt a little faint.

‘It is not too late to turn back. You may not like what you discover about yourself

‘You n-need not w-worry about me,’ stammered Wells.

‘As you wish,’ said Trêves, with the detachment of one washing his hands of the matter. He took a key from his pocket, opened the door and, gently but resolutely, propelled Wells over the threshold.

Wells held his breath as he ventured inside the room. He had taken a couple of faltering steps when he heard the surgeon close the door behind him. He gulped, glancing about the place Trêves had practically hurled him into once he had fulfilled his minor role in the disturbing ceremony. He found himself in a spacious suite of rooms containing various normal pieces of furniture. The ordinariness of the furnishings combined with the soft afternoon light filtering in through the window to create a prosaic, unexpectedly cosy atmosphere that clashed with the image of a monster’s lair. Wells stood transfixed for a few seconds, thinking his host would appear at any moment. When this did not happen, and not knowing what was expected of him, he wandered hesitantly through the rooms. He was immediately overcome by the unsettling feeling that Merrick was spying on him from behind one of the screens, but continued weaving in and out of the furniture, sensing this was another part of the ritual. But nothing he saw gave away the uniqueness of the rooms’ occupant: there were no half-eaten rats strewn about, or the remains of some brave knight’s armour.

In one of the rooms, however, he came across two chairs and a small table laid out for tea. He found this innocent scene still more unsettling, for he could not help comparing it to the gallows awaiting the condemned man in the town square, its joists creaking balefully in the spring breeze.

Then he noticed an intriguing object on a table next to the wall, beneath one of the windows. It was a cardboard model of a church. Wells walked over to marvel at the exquisite craftsmanship. Fascinated by the wealth of detail in the model, he did not at first notice the crooked shadow appearing on the wall: a stiff figure, bent over to the right crowned by an enormous head.

‘It’s the church opposite. I had to make up the parts I can’t see from the window’

The voice had a laboured, slurred quality.

‘It’s beautiful,’ Wells breathed, addressing the lopsided silhouette projected on the wall.

The shadow shook its head with great difficulty, unintentionally revealing to Wells what a struggle it was for Merrick to produce even this simple gesture to play down the importance of his own work. Having completed the arduous movement, he remained silent, stooped over his cane, and Wells realised he could not go on standing there with his back to him. The moment had arrived when he must turn and look his host in the face. Trêves had warned him that Merrick paid special attention to his guests’ initial reaction – the one that arose automatically, almost involuntarily, and which he therefore considered more genuine, more revealing than the faces people hurriedly composed to dissimulate their feelings once they had recovered from the shock. For those few brief moments, Merrick was afforded a rare glimpse into his guests’ souls, and it made no difference how they pretended to act during the subsequent meeting, since their initial reaction had already condemned or redeemed them. Wells was unsure whether Merrick’s appearance would fill him with pity or disgust. Fearing the latter, he clenched his jaw as tightly as he could, tensing his face to prevent it registering any emotion. He did not even want to show surprise, but merely to gain time before his brain could process what he was seeing and reach a logical conclusion about the feelings a creature as apparently deformed as Merrick produced in a person like him. In the end, if he experienced repulsion, he would willingly acknowledge this and reflect on it later, after he had left.

Wells drew a deep breath, planted his feet firmly on the ground, which had dissolved into a soft, quaking mass, and slowly turned to face his host. What he saw made him gasp. Just as Trêves had warned, Merrick’s deformities gave him a terrifying appearance. The photographs Wells had seen of him at the university which mercifully veiled his hideousness behind a blurred gauze, had not prepared him for this. He wore a dark grey suit and was propping himself up with a cane. Ironically, these accoutrements, which were intended to humanise him, only made him look more grotesque.

Teeth firmly clenched, Wells stood stiffly before him, struggling to suppress a physical urge to shudder. He felt as if his heart was about to burst out of his chest and beads of cold sweat trickled down his back, but he could not make out whether these symptoms were caused by horror or pity. Despite the unnatural tension of his facial muscles, he could feel his lips quivering, perhaps as they tried to form a grimace of horror, yet at the same time he noticed tears welling in his eyes so did not know what to think. Their mutual scrutiny went on for ever, and Wells wished he could shed at least one tear that would encapsulate his pain and prove to Merrick, and to himself, that he was a sensitive, compassionate being, but those pricking his eyes refused to brim over.

‘Would you prefer me to wear my hood, Mr Wells?’ asked Merrick, softly.

The strange voice, which gave his words a liquid quality as if they were floating in a muddy brook, struck renewed fear into Wells. Had the time limit Merrick usually put on his guests’ response expired? ‘No … that won’t be necessary’ he murmured.

His host moved his gigantic head laboriously in what Wells assumed was a nod of agreement.

‘Then let us have our tea before it goes cold,’ he said, shuffling to the table in the centre of the room.

Wells did not respond immediately, horrified by the way Merrick was obliged to walk. Everything was an effort for him, he realised, observing the complicated manoeuvres he had to make to sit down. Wells had to suppress an urge to rush over and help him, afraid this gesture usually reserved for the elderly or infirm might upset him. Hoping he was doing the right thing, he sat down as casually as possible in the chair opposite his host. Again, he had to force himself to sit still as he watched Merrick serve the tea. He mostly tried to fulfil this role using his left hand, which was unaffected by the disease, although he still employed the right to carry out minor tasks within the ceremony. Wells could not help but silently admire the extraordinary dexterity with which Merrick was able to take the lid off the sugar bowl or offer him a biscuit with a hand as big and rough as a lump of rock.

‘I’m so glad you were able to come, Mr Wells,’ said Merrick, after he had succeeded in the arduous task of serving the tea without spilling a single drop, ‘because it allows me to tell you in person how much I enjoyed your story.’

‘You are very kind, Mr Merrick,’ replied Wells.

Once it had been published, curious about how little impact it had made, Wells had read and reread it at least a dozen times to try to discover why it had been so completely overlooked. Imbued with a spirit of uncompromising criticism, he had weighed up the plot’s solidity, appraised its dramatic pace, considered the order, appropriateness, and even the number of words he had used, only to regard his first and quite possibly his last work of fiction with the unforgiving, almost contemptuous, eye with which the Almighty might contemplate the tiresome antics of a capuchin monkey. It was clear to him now that the story was a worthless piece of excrement: his writing a shameless imitation of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s pseudo-Germanic style, and his main character, Dr Nebogipfel, a poor, unrealistic copy of the exaggerated depictions of mad scientists already to be found in Gothic novels. Nevertheless, he thanked Merrick for his words of praise, smiling with false modesty and fearing they would be the only ones his writings ever received.

‘A time machine …’ said Merrick, delighting in the juxtaposition of words he found so evocative. ‘You have a prophetic imagination, Mr Wells.’

Wells thanked him again for this new and rather embarrassing compliment. How many more eulogies would he have to endure before he asked him to change the subject?

‘If I had a time machine like Dr Nebogipfel’s,’ Merrick went on dreamily, ‘I would travel back to ancient Egypt.’

Wells found the remark touching. Like any other person, this creature had a favourite period in history, as he must have a favourite fruit, season or song. ‘Why is that?’ he asked, with a friendly smile, providing his host with the opportunity to expound on his tastes.

‘Because the Egyptians worshipped gods with animals’ heads,’ replied Merrick, slightly shamefaced.

Wells stared at him stupidly. He was unsure what surprised him more: the naïve yearning in Merrick’s reply or the awkward bashfulness that accompanied it, as though he were chiding himself for wanting such a thing, for preferring to be a god worshipped by men instead of the despised monster he was. If anyone had a right to feel hatred and bitterness towards the world, surely he did. And yet Merrick reproached himself for his sorrow, as though the sunlight through the window-pane warming his back or the clouds scudding across the sky ought to supply reason enough for him to be happy. Lost for words, Wells took a biscuit from the plate and nibbled it with intense concentration, as though he were making sure his teeth still worked.

‘Why do you think Dr Nebogipfel didn’t use his machine to travel into the future as well?’ Merrick then asked, in that unguent voice, which sounded as if it were smeared with butter. ‘Wasn’t he curious? I sometimes wonder what the world will be like in a hundred years.’

‘Indeed …’ murmured Wells, at a loss to respond to this remark, too.

Merrick belonged to that class of reader who was able to forget with amazing ease the hand moving the characters behind the scenes of a novel. As a child Wells had also been able to read in that way. But one day he had decided he would be a writer, and from that moment on he had found it impossible to immerse himself in stories with the same innocent abandon: he was aware that characters’ thoughts and actions were not his. They answered to the dictates of a higher being, to someone who, alone in his room, moved the pieces he himself had placed on the board, more often than not with an overwhelming feeling of indifference that bore no relation to the emotions he intended to arouse in his readers. Novels were not slices of life but more or less controlled creations reproducing slices of imaginary, polished lives, where boredom and the futile, useless acts that make up any existence were replaced with exciting, meaningful episodes. At times, Wells longed to be able to read in that carefree, childlike way again but, having glimpsed behind the scenes, he could only do this with an enormous leap of his imagination. Once you had written your first story there was no turning back. You were a deceiver and you could not help treating other deceivers with suspicion.

It occurred to Wells briefly to suggest that Merrick ask Nebogipfel himself, but he changed his mind, unsure whether his host would take his riposte as the gentle mockery he intended. What if Merrick really was too naïve to tell the difference between reality and a simple work of fiction? What if this sad inability and not his sensitivity allowed him to experience the stories he read so intensely? If so, Well’s rejoinder would sound like a cruel jibe, aimed at wounding his ingenuousness. Fortunately, Merrick fired another question at him, which was easier to answer: ‘Do you think somebody will one day invent a time machine?’

‘I doubt such a thing could exist,’ replied Wells, bluntly.

‘And yet you’ve written about it!’ his host exclaimed, horrified.

‘That’s precisely why, Mr Merrick,’ he explained, trying to think of a simple way to bring together the various ideas underlying his conception of literature. ‘I assure you that if it were possible to build a time machine I would never have written about it. I am only interested in writing about what is impossible.’

At this, he recalled a quote from Lucian of Samosata’s True Histories, which he could not help memorising because it perfectly summed up his thoughts on literature: ‘I write about things I have neither seen nor verified nor heard about from others and, in addition, about things that have never existed and could have no possible basis for existing.’ Yes, as he had told his host, he was only interested in writing about things that were impossible. Dickens was there to take care of the rest, he thought of adding, but did not. Trêves had told him Merrick was an avid reader. He did not want to risk offending him if Dickens happened to be one of his favourite authors.

‘Then I’m sorry that because of me you’ll never be able to write about a man who is half human, half elephant,’ murmured Merrick.

Once more, Wells was disarmed. After he had spoken, Merrick’s gaze wandered to the window. Wells was unsure whether the gesture was meant to express regret or to give him the opportunity to study Merrick’s appearance as freely as he wished. In any case, Wells’s eyes were unconsciously, irresistibly, almost hypnotically drawn to him, confirming what he already knew full well – that Merrick was right: if he had not seen him with his own eyes, he would never have believed such a creature could exist. Except, perhaps, in the fictional world of books.

‘You will be a great writer, Mr Wells,’ his host declared, continuing to stare out of the window.

‘I wish I could agree,’ replied Wells, who, following his first failed attempt, was entertaining serious doubts about his abilities.

Merrick turned to face him. ‘Look at my hands, Mr Wells,’ he said, holding them out. ‘Would you believe that these hands could make a church out of cardboard?’

Wells gazed at his host’s mismatched hands. The right was enormous and grotesque while the left looked like that of a ten-year-old girl. ‘I suppose not,’ he admitted.

Merrick nodded slowly. ‘It is a question of will, Mr Wells,’ he said, striving for a tone of authority. ‘That’s all.’

Coming from anyone else’s mouth these words might have struck Wells as trite, but uttered by the man in front of him they became an irrefutable truth. This creature was living proof that man’s will could move mountains and part seas. In that hospital wing, a refuge from the world, the distance between the attainable and the unattainable was more than ever a question of will. If Merrick had built that cardboard church with his deformed hands, what might not he, Wells, be capable of? He was only prevented from doing whatever he wanted by his lack of self-belief

He could not help agreeing, which seemed to please Merrick, judging from the way he fidgeted in his seat. In an embarrassed voice, Merrick went on to confess that the model was to be a gift for a stage actress with whom he had been corresponding for several months. He referred to her as Mrs Kendall, and from what Wells could gather she was one of his most generous benefactors. He had no difficulty in picturing her as woman of good social standing, sympathetic to the suffering of the world, so long as they were not on her doorstep. She had discovered in the Elephant Man a novel way of spending the money she usually donated to charity. When Merrick explained that he was looking forward to meeting her in person when she returned from her tour in America, Wells could not help smiling, touched by the amorous note that, consciously or not, had slipped into his voice. But at the same time he felt a pang of sorrow, and hoped Mrs Kendall’s work would delay her in America so that Merrick could go on believing in the illusion of her letters and not be faced with the discovery that impossible love was only possible in books.

After they had finished their tea, Merrick offered Wells a cigarette, which he courteously accepted. They rose from their seats and went to the window to watch the sunset. For a few moments, the two men stood staring down at the street and at the façade of the church opposite, every inch of which Merrick must have been familiar with. People came and went, a pedlar with a handcart hawked his wares, and carriages trundled over the uneven cobblestones strewn with foul-smelling dung from the hundreds of horses going by each day. Wells watched Merrick gazing at the frantic bustle with almost reverential awe. He appeared to be lost in thought.

‘You know something, Mr Wells?’ he said finally. ‘I can’t help feeling sometimes that life is like a play in which I’ve been given no part. If you only knew how much I envy all those people …’

‘I can assure you, you have no reason to envy them, Mr Merrick,’ Wells replied abruptly. ‘Those people you see are specks of dust. Nobody will remember who they were or what they did after they die. You, however, will go down in history.’

Merrick appeared to mull over his words, as he studied his misshapen reflection in the window-pane.