По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

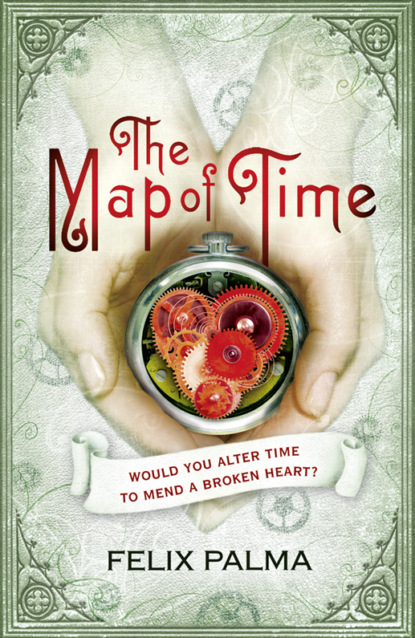

The Map of Time and The Turn of the Screw

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But they would not get the better of Wells. Certainly not. They would not confound him, for he had the basket.

He contemplated the wicker basket sitting on one of the kitchen shelves, and his spirits lifted, rebellious and defiant. The basket’s effect on him was instantaneous. As a result, he was never parted from it, lugging it around from pillar to post, despite the suspicions this aroused in his nearest and dearest. Wells had never believed in lucky charms or magical objects, but the curious way in which it had come into his life, and the string of positive events that had occurred since then, compelled him to make an exception in the case of the basket. He noticed that Jane had filled it with vegetables. Far from irritating him, this amused him. In allocating it that dull domestic function, his wife had at once disguised its magical nature and rendered it doubly useful: not only did the basket bring good fortune and boost his self-confidence, not only did it embody the spirit of personal triumph by evoking the extraordinary person who had made it, it was also just a basket.

Calmer now, Wells closed the magazine. He would not allow anyone to put down his achievements, of which he had reason to feel proud. He was thirty years old and, after a long, painful period of battling against the elements, his life had taken shape. The sword had been tempered and, of all the forms it might have taken, had acquired the appearance it would have for life. All that was needed now was to keep it honed, to learn how to wield it and, if necessary, allow it to taste blood occasionally. Of all the things he could have been, it seemed clear he would be a writer – he was one already. His three published novels testified to this. A writer. It had a pleasant ring to it. And it was an occupation that he was not averse to: since childhood it had been his second choice, after that of becoming a teacher – he had always wanted to stand on a podium and stir people’s consciences, but he could do that from a shop window, and perhaps in a simpler and more far-reaching way.

A writer. Yes, it had a pleasant ring. A very pleasant ring indeed.

Wells cast a satisfied eye over his surroundings, the home with which literature had provided him. It was a modest dwelling, but one that would have been far beyond his means a few years before, when he was barely scraping a living from the articles he managed to publish in local newspapers and the exhausting classes he gave, when only the basket kept him going in the face of despair.

He could not help comparing it with the house in Bromley where he had grown up, that miserable hovel reeking of the paraffin with which his father had doused the wooden floors to kill the armies of cockroaches. He recalled with revulsion the dreadful kitchen in the basement, with its awkwardly placed coal stove, and the back garden with the shed containing the foul-smelling outside privy, a hole in the ground at the bottom of a trodden-earth path that his mother was embarrassed to use – she imagined the employees of Mr Cooper, the tailor next door, watched her comings and goings. He remembered the creeper on the back wall, which he used to climb to spy on Mr Covell, the butcher, who was in the habit of strolling around his garden, like an assassin, forearms covered with blood, holding a dripping knife fresh from the slaughter. And in the distance, above the rooftops, the parish church and its graveyard crammed with decaying moss-covered headstones, below one of which lay the tiny body of his baby sister Frances, who, his mother maintained, had been poisoned by their evil neighbour Mr Munday during a macabre tea party.

No one, not even he, would have imagined that the necessary components could come together in that revolting hovel to produce a writer, and yet they had – although the delivery had been long drawn-out and fraught. It had taken him precisely twenty-one years and three months to turn his dreams into reality. According to his calculations, that was, for – as though he were addressing future biographers – Wells usually identified 5 June 1874 as the day upon which his vocation was revealed to him in what was perhaps an unnecessarily brutal fashion. That day he suffered a spectacular accident, and this experience, the enormous significance of which would be revealed over time, also convinced him that it was the whims of Fate and not our own will that shaped our future.

Like someone unfolding an origami bird in order to find out how it is made, Wells was able to dissect his present life and discover the elements that had gone into making it up. In fact, tracing the origins of each moment was a frequent pastime of his. This exercise in metaphysical classification was as comforting to him as reciting the twelve times table to steady the world each time it became a swirling mass. Thus, he had determined that the fateful spark to ignite the events that had turned him into a writer was something that might initially appear puzzling: his father’s lethal spin bowling on the cricket pitch. But when he pulled on that thread the carpet quickly unravelled: without his talent for spin bowling his father would not have been invited to join the county cricket team; had he not joined the county cricket team he would not have spent the afternoons drinking with his team-mates in the Bell, the pub near their house; had he not frittered away his afternoons in the Bell, neglecting the tiny china shop he ran with his wife on the ground floor of their dwelling, he would not have become acquainted with the pub landlord’s son; had he not forged those friendly ties with the strapping youth, when he and his sons bumped into him at the cricket match they were attending one afternoon, the lad would not have taken the liberty of picking young Bertie up by the arms and tossing him into the air; had he not tossed Bertie into the air, Bertie would not have slipped out of his hands; had he not slipped out of the lad’s hands, the eight-year-old Wells would not have fractured his tibia when he fell against one of the pegs holding down the beer tent; had he not fractured his tibia and been forced to spend the entire summer in bed, he would not have had the perfect excuse to devote himself to the only form of entertainment available to him in that situation – reading, a harmful activity, which, under any other circumstances, would have aroused his parents’ suspicions, which would have prevented him discovering Dickens, Swift and Washington Irving, the writers who planted the seed inside him that, regardless of the scant nourishment and care he could give it, would eventually come into bloom.

Sometimes, in order to appreciate the value of what he had even more, lest it lose its sparkle, Wells wondered what might have become of him if the miraculous sequence of events that had thrust him into the arms of literature had never occurred. And the answer was always the same. If the curious accident had never taken place, Wells was certain he would now be working in some pharmacy, bored witless and unable to believe that his contribution to life was to be of such little import. What would life be like without any purpose? He could imagine no greater misery than to drift through it aimlessly, frustrated, building an existence interchangeable with that of his neighbour, aspiring only to the brief, fragile and elusive happiness of simple folk. Fortunately, his father’s lethal bowling had saved him from mediocrity, turning him into someone with a purpose – turning him into a writer.

The journey had by no means been an easy one. It was as if just as he glimpsed his vocation, just as he knew which path to take, the wind destined to hamper his progress had risen, like an unavoidable accompaniment, a fierce, persistent wind in the form of his mother. For it seemed that, besides being one of the most wretched creatures on the planet, Sarah Wells’s sole mission in life was to bring up her sons, Bertie, Fred and Frank, to be hard-working members of society, which for her meant becoming a shop assistant, a baker or some other selfless soul, who, like Atlas, proudly but discreetly carried the world on their shoulders. Wells’s determination to amount to more was a disappointment to her, although one should not attach too much importance to that: it had merely added insult to injury.

Little Bertie had been a disappointment to his mother from the very moment he was born: he had had the gall to emerge from her womb a fully equipped male when, nine months earlier, she had only consented to cross the threshold of her despicable husband’s bedroom on condition he gave her a little girl to replace the one she had lost.

It was hardly surprising that, after such inauspicious beginnings, Wells’s relationship with his mother should continue in the same vein. Once the pleasant respite afforded by his broken leg had ended – after the village doctor had kindly prolonged it by setting the bone badly and being obliged to break it again to correct his mistake – little Bertie was sent to a commercial academy in Bromley, where his two brothers had gone before him. Their teacher, Mr Morley, had been unable to make anything of them. The youngest boy, however, soon proved that all the peas in a pod are not necessarily the same. Mr Morley was so astonished by Wells’s dazzling intelligence that he even turned a blind eye to the non-payment of his registration fee. However, such preferential treatment did not stop the mother uprooting her son from the milieu of blackboards and desks where he felt so at home, and sending him to train as an apprentice at the Rodgers and Denyer bakery in Windsor.

After three months of toiling from seven thirty in the morning until eight at night, with a short break for lunch in a windowless cellar, Wells feared his youthful optimism would begin to fade, as it had with his elder brothers – he barely recognised them as the cheerful, determined fellows they had once been. He did everything in his power to prove to all and sundry that he did not have the makings of a baker’s assistant, abandoning himself to frequent bouts of daydreaming, to the point at which the owners had no choice but to dismiss the young man who mixed up the orders and spent most of his time wool-gathering in a corner.

Thanks to the intervention of one of his mother’s second cousins, he was then sent to assist a relative in running a school in Wookey where he would also be able to complete his teacher-training. Unfortunately, this employment, far more in keeping with his aspirations, ended almost as soon as it had begun when it was discovered that the headmaster was an impostor: he had obtained his post by falsifying his academic qualifications.

The by-now-not-so-little Bertie once again fell prey to his mother’s obsessions. She deflected him from his true destiny by sending him off on another mistaken path. Aged just fourteen, Wells began work in the pharmacy run by Mr Cowap, who was instructed to train him as a chemist. However, the pharmacist soon realised the boy was far too gifted to be wasted on such an occupation, and placed him in the hands of Horace Byatt, headmaster at Midhurst Grammar School, who was on the lookout for exceptional students to imbue his establishment with the academic respectability it needed.

Wells easily excelled over the other boys, who were, on the whole, mediocre students, and was instantly noticed by Byatt, who contrived with the pharmacist to provide the talented boy with the best education they could. Wells’s mother soon frustrated the plot hatched by the pair of idle philanthropists, whose intention it had been to lead little Bertie astray, by sending her son to another bakery, this time in Southsea. Wells spent two years there in a state of intense confusion, trying to understand why that fierce wind insisted on blowing him off course each time he found himself on the right path.

Life at Edwin Hyde’s Bread Emporium was suspiciously similar to a sojourn in hell. It consisted of thirteen hours’ hard work, followed by a night spent shut in the airless hut that passed for a dormitory, where the apprentices slept so close together that even their dreams got muddled up. A few years earlier, convinced that her husband’s fecklessness would end by bankrupting the china-shop business, his mother had accepted the post of housekeeper at Uppark Manor, a rundown estate on Harting Down where, as a girl, she had worked as a maid. It was to here that Wells wrote her a series of despairing, accusatory letters – which, out of respect, I will not reproduce here – alternating childish demands with sophisticated arguments in a vain attempt to persuade her to set him free.

As he watched his longed-for future slip through his fingers, Wells did his utmost to weaken his mother’s resolve. He asked her how she expected him to help her in her old age on a shop assistant’s meagre wage: with the studies he intended to pursue he would obtain a wonderful position. He accused her of being intolerant, stupid, even threatened to commit suicide or other dreadful acts that would stain the family name for ever. None of this had any effect on his mother’s resolve to turn him into a respectable baker’s boy.

It took his former champion Horace Byatt, overwhelmed by growing numbers of pupils, to come to the rescue: he offered Wells a post at twenty pounds for the first year, and forty thereafter. Wells was quick to wave the figures in front of his mother, who reluctantly allowed him to leave the bakery. Relieved, the grateful Wells placed himself under the orders of his saviour, to whose expectations he was anxious to live up. During the day he taught the younger boys, and at night he studied to finish his teacher-training, eagerly devouring everything he could find about biology, physics, astronomy and other science subjects. The reward for his titanic efforts was a scholarship to the Normal School of Science in South Kensington, where he would study under none other than Professor Thomas Henry Huxley, the famous biologist who had been Darwin’s lieutenant during his debates with Bishop Wilberforce.

Despite all this, it could not be said that Wells left for London in high spirits. He did so more with deep unhappiness at not receiving his parents’ support in this huge adventure. He was convinced his mother hoped he would fail in his studies, confirming her belief that the Wells boys were only fit to be bakers, that no genius could possibly be produced from a substance as dubious as her husband’s seed. For his part, his father was the living proof that failure could be enjoyed as much as prosperity. During the summer they had spent together, Wells had looked on with dismay as his father, whom age had deprived of his sole refuge, cricket, clung to the one thing that had given his life meaning. He wandered around the cricket pitches like a restless ghost, carrying a bag stuffed with batting gloves, pads and cricket balls, while his china shop foundered like a captainless ship, holed in the middle of the ocean. Things being as they were, Wells did not mind having to stay in a rooming house where the guests appeared to compete in producing the most original noises.

He was so accustomed to life revealing its most unpleasant side to him that when his aunt Marie Wells proposed he lodge at her home on Euston Road, his natural response was suspicion, for the house was warm, cosy, suffused with a peaceful, harmonious atmosphere, and bore no resemblance to the squalid dwellings he had lived in up until then. He was so grateful to his aunt for providing him with this long-awaited reprieve in the interminable battle that was his life that he considered it almost his duty to ask for the hand of her daughter Isabel, a gentle, kind girl, who wafted silently around the house.

But Wells soon realised the rashness of his decision: after the wedding, which was settled with the prompt matter-of-factness of a tedious formality, he confirmed what he had already suspected, that his cousin had nothing in common with him. He also discovered that Isabel had been brought up to be a perfect wife, that is to say, to satisfy her husband’s every need except, of course, in the marriage bed, where she behaved with the coldness ideal for a procreating machine but entirely unsuited to pleasure. In spite of all this, his wife’s frigidity proved a minor problem, easily resolved by visiting other beds. Wells soon discovered an abundance of delightful alternatives to which his hypnotic grandiloquence gained him entry, and dedicated himself to enjoying life now that it seemed to be going his way.

Immersed in the modest pursuit of pleasure that his guinea-a-week scholarship allowed, Wells gave himself over to the joys of the flesh, to making forays into hitherto unexplored subjects, such as literature and art, and to enjoying every second of his hard-earned stay at South Kensington. He also decided the time had come to reveal his innermost dreams to the world by publishing a short story in the Science Schools Journal.

He called it The Chronic Argonauts and its main character was a mad scientist, Dr Nebogipfel, who had invented a machine he used to travel back in time to commit a murder. Time travel was not an original concept: Dickens had already written about it in A Christmas Carol and Edgar Allan Poe in ‘A Tale of the Ragged Mountains’, but in both of those stories the journeys always took place during a dream or state of trance. By contrast, Wells’s scientist travelled of his own free will and by means of a mechanical device. In brief, his idea was brimming with originality. However, this first tentative trial at being a writer did not change his life, which, to his disappointment, carried on exactly as before.

All the same, his first story brought him the most remarkable reader he had ever had, and probably would ever have. A few days after its publication, Wells received a card from an admirer who asked if he would accept to take tea with him. The name on the card sent a shiver down his spine: Joseph Merrick, better known as the Elephant Man.

Chapter XII

Wells began to hear about Merrick the moment he set foot in the biology classrooms at South Kensington. For those studying the workings of the human body, Merrick was something akin to Nature’s most amazing achievement, its finest-cut diamond, living proof of the scope of its inventiveness. The so-called Elephant Man suffered from a disease that had horribly deformed his body, turning him into a shapeless, almost monstrous creature. This strange affliction, which had the medical profession scratching its heads, had caused the limbs, bones and organs on his right side to grow uncontrollably, leaving his left side practically unaffected. An enormous swelling on the right side of his skull, for example, distorted the shape of his head, squashing his face into a mass of folds and bony protuberances, and even dislodging his ear. Because of this, Merrick was unable to express anything more than the frozen ferocity of a totem. Owing to this lopsidedness, his spinal column curved to the right, where his organs were markedly heavier, lending all his movements a grotesque air. As if this were not enough, the disease had also turned his skin into a coarse, leathery crust, like dried cardboard, covered with hollows and swellings and wart-like growths.

To begin with Wells could scarcely believe that such a creature existed, but the photographs secretly circulating in the classroom soon revealed to him the truth of the rumours. The photographs had been stolen or purchased from staff at the London Hospital, where Merrick now resided, having spent half his life being displayed in side-shows at third-rate fairs and travelling circuses. As they passed from hand to hand, the blurred, shadowy images in which Merrick was scarcely more than a blotch caused a similar thrill to the photographs of scantily clad women they became mixed up with, although for different reasons.

The idea of having been invited to tea with this creature filled Wells with a mixture of awe and apprehension. Even so, he arrived on time at the London Hospital, a solid, forbidding structure located in Whitechapel. In the entrance a steady stream of doctors and nurses went about their mysterious business. Wells looked for a place where he would not be in the way, his head spinning with the synchronised activity in which everyone seemed to be engaged, like dancers in a ballet. Perhaps one of the nurses he saw carrying bandages had just left an operating theatre where some patient was hovering between life and death. If so, she did not quicken her step beyond the brisk but measured pace evolved over years of dealing with emergencies. Amazed, Wells had been watching the non-stop bustle from his vantage-point for some time when Dr Trêves, the surgeon responsible for Merrick, finally arrived.

Trêves was a small, excitable man of about thirty-five who masked his childlike features behind a bushy beard, clipped neatly like a hedge. ‘Mr Wells?’ he enquired, trying unsuccessfully to hide the evident dismay he felt at the author’s offensive youthfulness.

Wells nodded, and gave an involuntary shrug as if apologising that he did not demonstrate the venerable old age Trêves apparently required of those visiting his patient. He instantly regretted his gesture, for he had not requested an audience with the hospital’s famous guest.

‘Thank you for accepting Mr Merrick’s invitation,’ said Trêves. The surgeon had quickly recovered from his initial shock and reverted to the role of intermediary.

With extreme respect, Wells shook his capable, agile hand, which was accustomed to venturing into places out of bounds to most other mortals. ‘How could I refuse to meet the only person who has read my story?’ he retorted.

Trêves nodded vaguely, as though the vanity of authors and their jokes were of no consequence to him. He had more important things to worry about. Each day, new and ingenious diseases emerged that required his attention, the extraordinary dexterity of his hands, and his vigorous resolve in the operating theatre. He gestured to Wells with an almost military nod that he should follow him up a staircase to the upper floors of the hospital. A relentless throng of nurses descending in the opposite direction hampered their ascent, nearly causing Wells to lose his footing on more than one occasion.

‘Not everybody accepts Joseph’s invitations, for obvious reasons,’ Trêves said, raising his voice almost to a shout, ‘although, strangely, this does not sadden him. Sometimes I think he is more than satisfied with the little he gets out of life. Deep down, he knows his bizarre deformities are what enable him to meet any bigwig he wishes to in London, something unthinkable for your average commoner from Leicester.’

Wells thought Treves’s observation in rather poor taste, but refrained from making any comment because he had immediately realised he was right: Merrick’s appearance, which had hitherto condemned him to a life of ostracism and misery, now permitted him to hobnob with the cream of London society, although it remained to be seen whether or not he considered his various deformities too high a price to pay for rubbing shoulders with the aristocracy.

The same hustle and bustle reigned on the upper floor, but with a few sudden turns down dimly lit corridors, Trêves had guided his guest away from the persistent clamour. Wells followed as he strode along a series of never-ending, increasingly deserted passageways. As they penetrated the furthest reaches of the hospital, the diminishing numbers of patients and nurses clearly related to the wards and surgeries becoming progressively more specialised. However, Wells could not help comparing this gradual extinction of life to the terrible desolation surrounding the monsters’ lairs in children’s fables. All that was needed were a few dead birds and some gnawed bones.

While they walked, Trêves used the opportunity to tell Wells how he had become acquainted with his extraordinary patient. In a detached, even tone that betrayed the tedium he felt at having to repeat the story yet again, Trêves explained he had met Merrick four years earlier, shortly after being appointed head surgeon at the hospital. A circus had pitched its tent on a nearby piece of wasteland, and its main attraction, the Elephant Man, was the talk of all London. If what people said about him was true, he was the most deformed creature on the planet. Trêves knew that circus owners were in the habit of creating freaks with the aid of fake limbs and makeup that were impossible to spot in the gloom, but he also acknowledged that this sort of show was the last refuge for those unfortunate enough to be born with a defect that earned them society’s contempt.

The surgeon had had few expectations when he visited the fair, motivated purely by unavoidable professional curiosity. But there was nothing fake about the Elephant Man. After a rather sorry excuse for a trapeze act, the lights dimmed and the percussion launched into a poor imitation of tribal drumming in an overlong introduction that nevertheless succeeded in giving the audience a sense of trepidation. Trêves watched, astonished, as the fair’s main attraction entered, and saw with his own eyes that the rumours circulating fell far short of reality. The appalling deformities afflicting the creature who dragged himself across the ring had transformed him into a misshapen figure resembling a gargoyle. When the performance was over, Trêves convinced the circus owner to let him meet the creature in private. Once inside his modest wagon, the surgeon thought he was in the presence of an imbecile, convinced the swellings on his head must inevitably have damaged his brain.

But he was mistaken. A few words with Merrick were enough to show Trêves that the hideous exterior concealed a courteous, educated, sensitive being. He explained to the surgeon that he was called the Elephant Man because he had had a fleshy protuberance between his nose and upper lip, a tiny trunk measuring about eight inches. It had made it hard for him to eat and had been unceremoniously removed a few years before. Trêves was moved by his gentleness, and because, despite the hardship and humiliation he had suffered, he apparently bore no resentment towards the humanity Trêves was so quick to despise when he could not get a cab or a box at the theatre.

When the surgeon left the circus an hour later, he had firmly resolved to do everything in his power to take Merrick away from there and offer him a decent life. His reasons were clear: in no other hospital records in the world was there any evidence of a human being with such severe deformities as Merrick’s. Whatever this strange disease was, of all the people in the world, it had chosen to reside in his body alone, transforming the wretched creature into a unique individual, a rare species of butterfly that had to be kept behind glass. Clearly, Merrick must leave the circus in which he was languishing at the earliest opportunity. Little did Trêves know that in order to accomplish the admirable goal he had set himself, he would have to begin a long, arduous campaign that would leave him drained.

He started by presenting Merrick to the Pathology Society, but this led only to its distinguished members subjecting the patient to a series of probing examinations and ended in them becoming embroiled in fruitless, heated debates about the nature of the mysterious illness, which invariably turned into slanging matches where someone would always take the opportunity to try to settle old scores. However, his colleagues’ disarray, far from discouraging Trêves, heartened him: ultimately it underlined the importance of Merrick’s life, making it all the more imperative to remove him from the precarious world of show-business.

His next step had been to try to get him admitted to the hospital where he worked so that he could be easily examined. Unfortunately, hospitals did not provide beds for chronic patients, and consequently, although the management applauded Treves’s idea, their hands were tied. Faced with the hopelessness of the situation, Merrick himself suggested Trêves find him a job as a lighthouse keeper, or some other occupation that would cut him off from the rest of the world.

But Trêves would not admit defeat. Out of desperation, he went to the newspapers and, in a few weeks, managed to move the whole country with the wretched predicament of the fellow they called the Elephant Man. Donations poured in, but Trêves did not only require money: he wanted to give Merrick a decent home. He decided to turn to the only people who were above society’s absurd, hidebound rules: the royal family. He persuaded the Duke of Cambridge and the Princess of Wales to agree to meet the creature. Merrick’s refined manners and extraordinarily gentle nature did the rest. That was how Merrick had come to be a permanent guest in the hospital wing where Trêves and Wells now found themselves.

‘Joseph is happy here,’ declared Trêves, in a suddenly thoughtful voice. ‘The examinations we carry out on him from time to time are fruitless, but that does not seem to worry him. He is convinced his illness was caused by an elephant knocking down his heavily pregnant mother while she was watching a parade. Sadly, Mr Wells, this is a pyrrhic victory. I have found Merrick a home but I am unable to cure his illness. His skull is growing bigger by the day, and I’m afraid that soon his neck will be unable to support the incredible weight of his head.’

Treves’s blunt evocation of Merrick’s death, with the bleak desolation that seemed to permeate that wing of the hospital, plunged Wells into a state of extreme anxiety.

‘I would like his last days to be as peaceful as possible,’ the surgeon went on, oblivious to the pallor spreading over his companion’s face. ‘But apparently this is asking too much. Every night, the locals gather under his window shouting insults at him and calling him names. They even think he is to blame for killing the whores who have been found mutilated in the neighbourhood. Have people gone mad? Merrick couldn’t hurt a fly. I have already mentioned his extraordinary sensibility. Do you know that he devours Jane Austen’s novels? And, on occasion, I’ve even surprised him writing poems. Like you, Mr Wells.’

‘I don’t write poems, I write stories,’ Wells murmured hesitantly, his increasing unease apparently making him doubt everything.

Trêves scowled at him, annoyed that he would want to split hairs over what he considered such an inconsequential subject as literature.

‘That’s why I allow these visits,’ he said, shaking his head regretfully, before resuming where he had left off, ‘because I know they do him a great deal of good. I imagine people come to see him because his appearance makes even the unhappiest souls realise they should thank God. Joseph, on the other hand, views the matter differently. Sometimes I think he derives a sort of twisted amusement from these visits. Every Saturday, he scours the newspapers, then hands me a list of people he would like to invite to tea, and I obligingly forward them his card. They are usually members of the aristocracy, wealthy businessmen, public figures, painters, actors and other more or less well-known artists … People who have achieved a measure of social success and who in his estimation have one last test to pass: confronting him in the flesh. Joseph’s deformities are so hideous they invariably evoke either pity or disgust in those who see him. I imagine he can judge from his guests’ reaction whether they are the kind-hearted type or riddled with fears and anxieties.’