По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

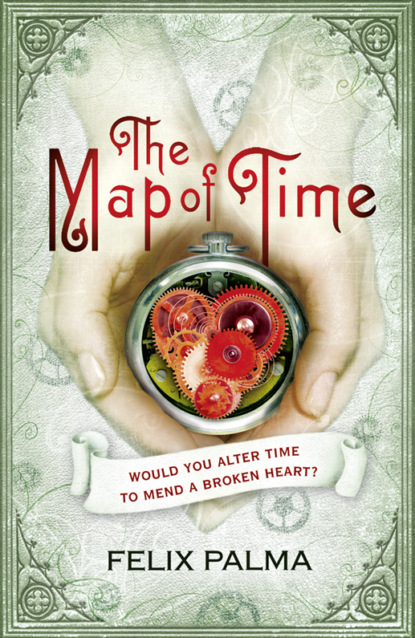

The Map of Time and The Turn of the Screw

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

From that moment on, the telegrams became Gilliam Murray’s reason for getting up in the morning. He awaited their arrival with eager anticipation, reading and rereading them behind the locked door of his office, unwilling for the time being to share the amazing discovery with anyone, not even his father.

According to the telegrams, once they had located the village, Kaufmann and Austin had no difficulty in being accepted as guests. In fact, the Reed People were apparently incapable of putting up any form of resistance. Neither did they seem particularly interested in the explorers’ reasons for being there. They simply accepted their presence. The two men asked for no more and, rather than lose heart when faced with the difficulty of carrying out the essential part of their mission (which was to discover whether or not these savages could open passageways to other worlds), they resolved to be patient and treat their stay as a paid holiday. Murray could imagine them lounging around in the sun all day, polishing off the crates of whisky they had sneaked with them on the expedition while he had pretended to be looking the other way.

Amazingly, they could not have thought up a better strategy, for their continual state of alcoholic stupor, and the frequent dancing and fighting they engaged in naked in the grass, drew the attention of the Reed People, who were curious about the amber liquid that generated such jolly antics. Once they began sharing their whisky, a rough camaraderie sprang up between them, which Murray rejoiced in back in his office, for it was without doubt the first step towards a future co-existence. He was not mistaken, although fostering this primitive contact until it grew into a common bond of trust and friendship cost him several consignments of the best Scotch. To this day he wondered whether so many bottles had really been necessary for such a small tribe.

At last, one morning, he received the long-awaited telegram, in which Kaufmann and Austin described how the Reed People had led them to the middle of the village and, in a seemingly beautiful gesture of friendship and gratitude, had opened for them the hole through to the other world. The explorers described the aperture and the pink landscape they had glimpsed through it, using exactly the same words as Tremanquai had employed five years earlier. This time, however, the young Murray no longer saw them as part of a made-up story: now he knew it was for real.

All of a sudden he felt trapped, suffocated, and not because he was locked away in his little office. He felt hemmed in by the walls of a universe he was now convinced was not the only one of its kind. But this constraint would soon end, he thought. He devoted a few moments to the memory of Oliver Tremanquai. He assumed that the man’s deep religious beliefs had prevented him from assimilating what he had seen, leaving him no other course than the precarious path of madness. Luckily, that pair of oafs, Kaufmann and Austin, possessed far simpler minds, which should spare them a similar fate.

He reread the telegram hundreds of times. Not only did the Reed People exist, they practised something that Murray, unlike Tremanquai, preferred to call magic, rather than witchcraft. An unknown world had opened itself up to Kaufmann and Austin, and naturally they could not resist exploring it.

As Murray read their subsequent telegrams, he regretted not having accompanied them. With the blessing of the Reed People, who left them to their own devices, the pair made brief incursions into the other world, diligently reporting its peculiarities. It consisted largely of a vast pink plain of faintly luminous rock, stretching out beneath a sky permanently obscured by incredibly dense fog. If there were any sun behind it, its rays were unable to shine through. As a consequence, the only light came from the strange substance on the ground, so that while one’s boots were clearly visible, the landscape was plunged into gloom, day and night merging into an eternal dusk, making it very difficult to see long distances. From time to time, a raging wind whipped the plain, producing sand storms that made everything even more difficult to see.

The two men had immediately noticed something strange: the moment they stepped through the hole their pocket watches stopped. Once back in their own reality the mechanisms mysteriously stirred again. It was as though they had unanimously decided to stop measuring the time their owners spent in the other world. Kaufmann and Austin looked at one another – it is not difficult to imagine them shrugging their shoulders, baffled.

They made a further discovery after spending a night, according to their calculations, in the camp they had set up right beside the opening so that they could keep an eye on the Reed People. There was no need for them to shave, because while they were in the other world their beards stopped growing. In addition, Austin had cut his arm seconds before stepping through the hole, and as soon as he was on the other side it had stopped bleeding, to the point that he had even forgotten to bandage it. He did not remember the wound until the moment they were back in the village and it bled again.

Intrigued, Gilliam Murray wrote down this extraordinary incident in his notebook, as well as what had happened with their watches and beards. Everything pointed to some impossible stoppage of time. While he speculated in his office, Kaufmann and Austin stocked up on ammunition and food and set out towards the only thing that broke the monotony of the plain: the ghostly mountain range, scarcely visible on the horizon.

As their watches continued to be unusable, they decided to measure the time their journey took by the number of nights they slept. This method soon proved ineffective, because at times the wind rose so suddenly and with such force they were obliged to stay awake all night holding the tent down, or their accumulated tiredness crept up on them when they stopped for food or rest. All they could say was that after an indeterminate length of time, which was neither very long nor very short, they reached the mountains. They proved to be made of the same luminous rock as the plain but had a hideous appearance, like a set of rotten, broken teeth, their jagged peaks piercing the thick clouds that blotted out the sky.

The two men spotted a few hollows that looked like caves. Having no other plan, they decided to scale the slopes until they reached the nearest one. This did not take long. Once they had reached the pinnacle of a small mountain, they had a broader view of the plain. Far off in the distance the hole had been reduced to a bright dot on the horizon. They could see their way back, acting as a guiding light. They were not worried that the Reed People might close the hole, because they had taken the precaution of bringing what remained of the whisky with them.

It was then that they noticed other bright dots shining in the distance. It was difficult to see clearly through the mist, but there must have been half a dozen. Were they more holes leading to other worlds?

They found the answer in the very cave they intended to explore. As soon as they entered it they could see it was inhabited. There were signs of life everywhere: burned-out fires, bowls, tools and other basic implements – things Tremanquai had found so conspicuous by their absence in the Reed People’s village. At the back of the cave they discovered a narrow enclosure, the walls of which were covered with paintings. Most depicted scenes from everyday life, and from the willowy rag-doll figures, only the Reed People could have painted them. Apparently, that dark world was where they really lived. The village was no more than a temporary location, a provisional settlement, perhaps one of many they had built in other worlds.

Kaufmann and Austin did not consider the drawings particularly significant. But two caught their attention. One of these took up nearly an entire wall. As far as they could tell it was meant to be a map of that world, or at least the part the tribe had succeeded in exploring, which was limited to the area near the mountains. What intrigued them was that this crude map marked the location of some other holes, and, if they were not mistaken, what they contained. The drawings were easy enough to interpret: a yellow star represented a hole, and the painted images next to it, the hole’s contents. At least, this was what they deduced from the dot surrounded by huts, apparently representing the hole the explorers had climbed through to get there and the village on the other side. The map showed four other openings, fewer than those the two men had glimpsed on the horizon. Where did they lead?

Whether from idleness or boredom, the Reed People had only painted the contents of the holes nearest their cave. One seemed to depict a battle between two different tribes: one human-shaped, the other square or rectangular. The remainder of the drawings were impossible to make out. Consequently, the only thing Kaufmann and Austin could be clear about was that the world they were in contained dozens of holes like the one they had come through, but they could only find out where any of them led if they passed through them: the Reed People’s scrawls were as mystifying as the dreams of a blind man.

The second painting that caught their eye was on the opposite wall and showed a group of Reed People running from what looked like a gigantic four-legged monster with a dragon’s tail and spikes on its back. Kaufmann and Austin glanced at one another, alarmed to find themselves in the same world as a wild animal whose mere image was enough to scare the living daylights out of them. What would happen if they came across the real thing? However, this discovery did not make them turn back. They both had rifles and enough ammunition to kill a whole herd of monsters, assuming they existed and were not simply a mythological invention. They also had whisky, which would fire up their courage – or, at least, turn the prospect of being eaten by an elephantine monster into a relatively minor nuisance. What more did they need?

Accordingly, they decided to carry on exploring, and set out for the opening where the battle was going on between the two tribes because it was closest to the mountains. The journey was gruelling, hampered by freak sandstorms that forced them to erect their tent and take refuge inside if they did not want to be scoured like cooking pots. Thankfully, they did not meet any of the giant creatures. Of course, when they finally reached the hole, they had no idea how long it had taken them to get there, only that the journey had been exhausting.

Its size and appearance were identical to the one they had first stepped through into that murky world. The only difference was that, instead of crude huts, inside this one there was a ruined city. Scarcely a single building remained standing, yet there was something oddly familiar about the structures. They stood for a few moments, surveying the ruins from the other side of the hole, as one would peer into a shop window, but no sign of life broke the calm. What kind of war could have wrought such terrible devastation?

Depressed by the dreadful scene, Kaufman and Austin restored their courage with a few slugs of whisky, then donned their pith helmets and leaped valiantly through the opening. Their senses were immediately assailed by an intense familiar odour. Smiling with bewilderment, it dawned on them that they were simply smelling their own world again: they had been unaware of it during their journey across the pink plain.

Rifles at the ready, they scoured their surroundings, moving cautiously through the rubble-filled streets, shocked at the sight of so much devastation, until they stumbled across another obstacle, which stopped them dead in their tracks. Kaufmann and Austin gazed incredulously at the object blocking their path: it was none other than the clock tower of Big Ben. It lay in the middle of the street like a severed fish head, the vast clock face a great eye staring at them with mournful resignation.

The discovery made them glance uneasily about them. Strangely moved, they cast an affectionate eye over each toppled edifice, the desolate ruined landscape where a few plumes of black smoke darkened the sky over a London razed to the ground. Neither could contain their tears. In fact, the two men would have stood there for ever, weeping over the remains of their beloved city, had it not been for a peculiar clanking sound that came from nearby.

Rifles at the ready again, they followed the clatter until they came to a small mound of rubble. They clambered up it noiselessly, crouching low. Unseen in their improvised lookout, they saw what was causing the racket. It was coming from strange, vaguely humanoid metal creatures, powered by what looked like tiny steam engines attached to their backs. The loud clanging noise they had heard was the sound of clumsy iron feet knocking against the metal debris strewn on the ground. The bemused explorers had no idea what these creatures might be, until Austin plucked from the rubble what looked like the crumpled page of a newspaper.

With trembling fingers, he opened it and discovered a photograph of the same creatures as the ones they could see below them. The headline announced the unstoppable advance of the automatons, and went on to encourage readers to rally to the support of the human army led by the brave Captain Derek Shackleton. What most surprised them, however, was the date: this loose page was from a newspaper printed 3 April 2000. As one, Kaufmann and Austin shook their heads, very slowly from left to right, but before they had time to express their amazement in a more sophisticated way, the remains of a rafter in the mound of rubble fell into the street with a loud crash, alerting the automatons.

Kaufmann and Austin exchanged terrified glances, and took to their heels, running full pelt towards the hole they had come through without looking back. They easily slipped through it again, but did not stop running until their legs would carry them no further.

They erected their tent and cowered inside, trying to collect their thoughts, to absorb what they had seen – with the obligatory help of some whisky, of course. It was clearly time for them to return to the village and report back to London everything they had seen. They were certain that Gilliam Murray would be able to explain it.

However, their problems did not end there. On the way back to the village, they were attacked by a gigantic beast with spikes on its back, whose potential existence they had forgotten about. They had great difficulty in killing it. They used up nearly all their ammunition trying to scare it away, because the bullets kept bouncing off the spiked armour without injuring it. Finally, they managed to chase it away by shooting at its eyes, its only weak point as far as they could determine.

Having successfully fought off the beast, they arrived back at the hole without further incident, and immediately sent a message to London relating all their discoveries.

As soon as he received their news, Gilliam Murray set sail for Africa. He joined the two explorers in the Reed People’s village where, like doubting Thomas plunging his fingers into Christ’s wounds after he had risen from the dead, he made his way to the razed city of London in the year 2000. He spent many months with the Reed People, although he could not be sure exactly how many as he spent extensive periods exploring the pink plain in order to verify Kaufmann and Austin’s claims.

Just as they had described in their telegrams, in that sunless world watches stopped ticking, razors became superfluous, and nothing appeared to mark the passage of time. Consequently he concluded that, incredible though it might seem, the moments he spent there were a hiatus in his life, a temporary suspension of his inexorable journey towards death. He realised his imagination had not been playing tricks on him when he returned to the village and the puppy he had taken with him ran to join its siblings: they had all come from the same litter but now the others were grown dogs. Gilliam had not needed to take a single shave during his exploration of the plain, but Eternal, the puppy, was a far more spectacular manifestation of the absence of time in the other world.

He also deduced that the holes did not lead to other universes, as he had first believed, but to different times in a world that was none other than his own. The pink plain was outside the time continuum, outside time, the arena in which man’s life took place alongside that of plants and other animals. And the beings inhabiting that world, Tremanquai’s Reed People, knew how to break out of the time continuum by creating holes in it that enabled man to travel in time, to cross from one era to another.

This realisation filled Murray with excitement and dread. He had made the greatest discovery in the history of mankind: he had discovered what lay underneath the world, what lay behind reality. He had discovered the fourth dimension.

How strange life was, he thought. He had started out trying to find the source of the Nile, and ended up discovering a secret passage that led to the year 2000. But that was how all the greatest discoveries were made. Had not the voyage of the Beagle been prompted by spurious financial and strategic interests? The discoveries resulting from it would have been far less interesting had a young naturalist perceptive enough to notice the variations between finches’ beaks not been on board. And yet the story of natural selection would revolutionise the world. His discovery of the fourth dimension had happened in a similarly random way.

But what use was there in discovering something if you could not share it with the rest of the world? Gilliam wanted to take Londoners to the year 2000 so that they could see with their own eyes what the future held for them. The question was: how? He could not possibly take boatloads of city-dwellers to a native village in the heart of Africa, where the Reed People were living. The only answer was to move the hole to London. Was that possible? He did not know, but he would lose nothing by trying.

Leaving Kaufmann and Austin to guard the Reed People, Murray returned to London, where he built a cast-iron box the size of a room. He took it, with a thousand bottles of whisky, to the village, where he planned to strike a bargain that would change people’s perception of the known world. Drunk as lords, the Reed People consented to his whim of singing their magic chants inside the sinister box. Once the hole had materialised, he herded them out and closed the heavy doors behind them. The three men waited until the last of the Reed People had succumbed to the effects of the whisky before setting off for home.

It was an arduous journey, and only when the enormous box was on the ship at Zanzibar did Murray begin to breathe more easily. Even so, he barely slept a wink during the passage. He spent almost the entire time on deck, gazing lovingly at the fateful box and wondering whether it was not in fact empty. Could one really steal a hole? His eagerness to know the answer to that question gnawed at him, making the return journey seem interminable. He could hardly believe it when at last they docked at Liverpool.

As soon as he reached his offices, he opened the box in complete secret. The hole was still there! They had successfully stolen it! The next step was to show it to his father.

‘What the devil is this?’ exclaimed Sebastian Murray, when he saw the hole shimmering inside the box.

‘This is what drove Oliver Tremanquai mad, Father,’ Gilliam replied, pronouncing the explorer’s name with affection. ‘So, take care.’

His father turned pale. Nevertheless, he accompanied his son through the hole and travelled into the future, to a demolished London where humans hid in the ruins like rats. Once he had got over the shock, father and son agreed they must make this discovery known to the world. And what better way to do this than to turn the hole into a business? Taking people to see the year 2000 would bring in enough money to cover the cost of the journeys and to fund further exploration of the fourth dimension.

They proceeded to map out a secure route to the hole into the future, eliminating any dangers, setting up lookout posts and smoothing the road so that a tramcar with thirty seats could cross it easily. Sadly, his father did not live long enough to see Murray’s Time Travel open its doors to the public, but Murray consoled himself with the thought that at least he had seen the future beyond his own death.

Chapter IX

Once he had finished telling his story, Murray fell silent and looked expectantly at his two visitors. Andrew assumed he was hoping for some kind of response, but had no idea what to say. He felt embarrassed. Everything his host had told them was no more believable than an adventure story. That pink plain seemed about as real to him as Lilliput, the South Sea Island inhabited by little people where Lemuel Gulliver had been shipwrecked. From the stupefied smile on Charles’s face, however, he assumed his cousin did believe it. After all, he had travelled to the year 2000: what did it matter whether he had got there by crossing a pink plain where time had stopped?

‘And now, gentlemen, if you would kindly follow me, I’ll show you something only a few trusted people are allowed to see,’ Murray declared, resuming the guided tour of his commodious office.

With Eternal continually running round his master, the three men walked across to another wall, where a small collection of photographs awaited them with what was probably another map, although this was concealed behind a red silk curtain. Andrew was surprised to discover that the photographs had been taken in the fourth dimension, although they might easily have depicted any desert, since cameras were unable to record the colour of this or any other world. He had to use his imagination, then, to see the white smear of sand as pink. The majority documented routine moments during the expedition: Murray and two other men, presumably Kaufmann and Austin, putting up tents; drinking coffee during a pause; lighting a fire; posing in front of the phantom mountains, almost entirely obscured by thick fog. It all looked too normal.

Only one of the images made Andrew feel he was contemplating an alien world. In it Kaufmann (who was short and fat) and Austin (who was tall and thin) stood smiling exaggeratedly, hats tilted to the side of their heads, rifles hanging from their shoulders, and one boot resting on the massive head of a fairy-tale dragon, which lay dead on the sand like a hunting trophy. Andrew was about to lean towards it and take a closer look at the amorphous lump, when an awful screeching noise made him start. Beside him, Murray was pulling a gold cord, which drew back the silk curtain, revealing what was behind it.

‘Rest assured, gentlemen, you will find no other map like it anywhere in England,’ he declared, swelling with pride. ‘It is an exact replica of the drawing in the Reed People’s cave, expanded, naturally, after our subsequent explorations.’

What the puppet-theatre curtain had uncovered looked more like a drawing by a child with an active imagination than a map. The colour pink predominated, of course, representing the plain, with the mountains in the middle. But the shadowy peaks were not the only geological feature on the map: in the right-hand corner, for example, there was a squiggly line, presumably a river, and close by it a light-green patch, possibly a forest or meadow. Andrew could not help feeling that these everyday symbols, used in maps that charted the world he lived in, were incongruous in what was supposed to be a map of the fourth dimension. But the most striking thing about the drawing was the gold dots peppering the plain, evidently meant to symbolise the holes. Two – the entrance to the year 2000, and the one now in Murray’s possession – were linked by a thin red line, which must represent the route taken by the time-travelling tramcar.

‘As you can see, there are many holes, but we still have no idea where they lead. Does one of them go back to the autumn of 1888? Who knows? It is certainly possible,’ said Murray, staring significantly at Andrew. ‘Kaufmann and Austin are trying to reach the one nearest the entrance to the year 2000, but they still haven’t found a way to circumnavigate the herd of beasts grazing in the valley right in front of it.’

While Andrew and Charles studied the map, Murray knelt down to stroke the dog. ‘Ah, the fourth dimension. What mysteries it holds,’ he mused. ‘All I know is that our candle never burns out there, to use a poetic turn of phrase. Eternal only looks one, but he was born four years ago. And I suppose that must be his actual age – unless the long periods he has spent on the plain, where time seems to leave no mark, are of no matter. Eternal was with me while I carried out my studies in Africa, and since we came back to London, he sleeps next to me every night inside the hole. I did not name him “Eternal” for nothing, gentlemen, and while I can, I’ll do everything in my power to honour his name.’