По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

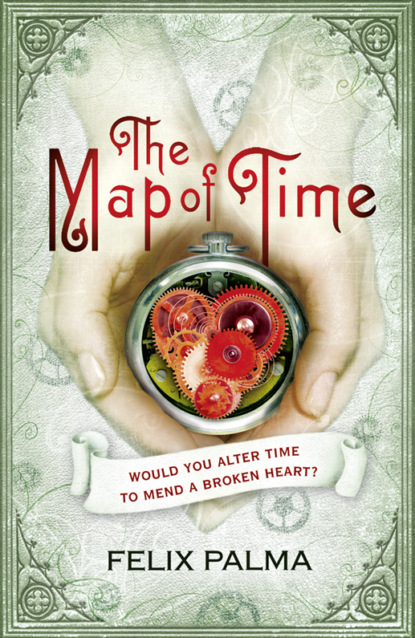

The Map of Time and The Turn of the Screw

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Andrew took a deep breath. The moment had come for him to destroy his life. ‘And the woman who has stolen my heart,’ he declared, ‘is a Whitechapel whore by the name of Marie Kelly’

Having unburdened himself, he smiled defiantly at the gathering. Faces fell, heads were clutched in hands, arms flapped in the air, but no one said a word: they all knew they were witnessing a melodrama with two protagonists and, of course, that William Harrington must speak. All eyes were fixed on the host.

Staring at the pattern on the carpet, his father shook his head, let out a low, barely repressed growl, and put down his glass on the mantelpiece, as though it were suddenly encumbering him.

‘Contrary to what I’ve heard you maintain, gentlemen,’ Andrew went on, unaware of the rage stirring in his father’s breast, ‘whores aren’t whores because they want to be. I assure you that any one of them would choose to have a respectable job if they could. Believe me, I know what I’m saying.’ His father’s colleagues continued to demonstrate their ability to express surprise without opening their mouths. ‘I’ve spent a lot of time in their company, these past few weeks. I’ve watched them washing in horse-troughs in the mornings, seen them sitting down to sleep, held against the wall by a rope if they could not find a bed …’

The more he went on speaking in this way about prostitutes, the more Andrew realised his feelings for Marie Kelly were deeper than he had imagined. He gazed round with infinite pity at the men with their orderly lives, their dreary, passionless existences, who would consider it impractical to yield to a near-uncontrollable urge. He could tell them what it was like to lose one’s head, to burn up with feverish desire. He could tell them what the inside of love looked like, because he had split it open like a piece of fruit.

But Andrew could not tell them this or anything else because at that moment his father, emitting enraged grunts, strode unsteadily across the room, almost harpooning the carpet with his cane. Without warning, he struck his son hard across the face. Andrew staggered backwards, stunned by the blow. When he finally understood what had happened, he rubbed his stinging cheek, trying to put on the same smile of defiance. For a few moments that seemed like eternity to those present, father and son stared at one another in the middle of the room, until William Harrington said: ‘As of tonight I have only one son.’

Andrew tried not to show any emotion. ‘As you wish,’ he replied coldly. Then, to the guests, he made as if to bow. ‘Gentlemen, my apologies, I must leave this place for ever.’

With as much dignity as he could muster, Andrew turned on his heel and left the room. The cold night air had a calming effect on him. In the end, he thought, trying not to trip as he descended the steps, nothing that had happened had come as a surprise. His disgraced father had just disinherited him, in front of half of London’s wealthiest businessmen, giving them a first-hand display of his famous temper, unleashed against his offspring without the slightest compunction. Now Andrew had nothing, except his love for Marie Kelly. If before the disastrous encounter he had entertained the slightest hope that his father might give in, and even let him bring his beloved to the house, to remove her from the monster stalking Whitechapel, it was clear now that they must live by their own means. He climbed into the carriage and ordered Harold to return to Miller’s Court.

The coachman, who had been pacing round the vehicle in circles, waiting for the dénouement of the drama, clambered back onto the box and urged the horses on. He was trying to imagine what had taken place inside the house – and to his credit, based on the clues he had been perceptive enough to pick up, we must say that his reconstruction of the scene was remarkably accurate.

When the carriage stopped in the usual place, Andrew got out and hurried towards Dorset Street, anxious to embrace Marie Kelly and tell her how much he loved her. He had sacrificed everything for her. Still he had no regrets, only a vague uncertainly regarding the future. But they would manage. He was sure he could rely on Charles. His cousin would lend him enough money to rent a house in Vauxhall or Warwick Street, at least until they were able to find decent jobs that would allow them to fend for themselves. Marie Kelly could find work at a dressmaker’s – but what skills did he possess? It made no difference. He was young, able-bodied and willing. He would find something. The main thing was he had stood up to his father, and what happened next was neither here nor there. Marie Kelly had pleaded with him, silently, to take her away from Whitechapel, and that was what he intended to do, with or without anyone else’s help. They would leave that accursed neighbourhood, that outpost of hell.

Andrew glanced at his watch as he paused beneath the stone archway into Miller’s Court. It was five o’clock in the morning. Marie Kelly would probably have already returned to the room, probably as drunk as he. Andrew visualised them communicating through a haze of alcohol in gestures and grunts like Darwin’s primates. With boyish excitement, he walked into the yard where the flats stood. The door to number thirteen was closed. He banged on it a few times but got no reply. She must be asleep, but that would not be a problem. Careful not to cut himself on the shards of glass sticking out of the window frame, Andrew reached through the hole and flicked open the door catch, as he had seen Marie do after she had lost her key. ‘Marie, it’s me,’ he said, opening the door. ‘Andrew’

Allow me at this point to break off the story to warn you that what took place next is hard to relate, because the sensations Andrew experienced were apparently too numerous for a scene lasting only a few seconds. That is why I need you to take into account the elasticity of time, its ability to expand or contract like an accordion, regardless of clocks. I am sure this is something you will have experienced frequently in your own life, depending on which side of the bathroom door you have found yourself. In Andrew’s case, time expanded in his mind, creating an eternity of a few seconds. I am going to describe the scene from that perspective, and therefore ask you not to blame my inept story-telling for the discrepancies you will no doubt perceive between the events and their correlation in time.

When he first opened the door and stepped into the room, Andrew did not understand what he was seeing or, more precisely, he refused to accept what he was seeing. During that brief but endless moment, he still felt safe, although the certainty was forming in some still-functioning part of his brain that what he saw before him would kill him. Nobody could be faced with a thing like that and go on living, at least not completely. And what he saw before him, let’s be blunt about it, was Marie Kelly – but at the same time it wasn’t, for it was hard to accept that the object lying on the bed in the middle of all the blood was she.

Andrew could not compare what awaited him in that room with anything he had seen before because, like most other men, he had never been exposed to a carefully mutilated human body. And once Andrew’s brain had finally accepted that he was indeed looking at a meticulously destroyed corpse, although nothing in his pleasant life of country-house gatherings and fancy headwear seemed to offer him any clues, he had no time to feel the appropriate revulsion: he could not avoid the terrible line of reasoning that led him to the inevitable conclusion that this human wreckage must be his beloved.

The Ripper, for this could be the work of none other, had stripped the flesh off her face, rendering her unrecognisable, and yet, however great the temptation, Andrew could not deny the corpse belonged to Marie Kelly. It seemed an almost simplistic, not to say improbable, approach, but given its size and appearance and, above all, the place where he had found it, the dismembered corpse could only be that of Marie Kelly.

After this, of course, Andrew was overcome by a devastating pain, which, despite everything, was only a pale expression of what it would later become: it was still tempered by the shock paralysing and, to some extent, protecting him. Once he was convinced he was standing before the corpse of his beloved, he felt compelled by a sort of posthumous loyalty to look tenderly upon that ghastly sight, but he was incapable of contemplating with anything other than revulsion her flayed face, the skull’s macabre, caricatured smile peeping through the strips of flesh.

But how could the skull on which he had bestowed his last passionate kisses revolt him now? The same applied to the body he had worshipped for nights on end, and which, ripped open and half skinned, he now found sickening. It was clear to him from his reaction that in some sense, although it was made of the same material, this object had ceased to be Marie Kelly. The Ripper, in his zeal to discover how she was put together inside, had reduced her to a simple casing of flesh, robbing her of her humanity.

After this last reflection, the time came for Andrew to focus, with a mixture of fascination and horror, on specific details, like the darkish brown lump between her feet, possibly her liver, or the breast lying on the bedside table, which, far from its natural habitat, he might have mistaken for a soft bun had it not been topped with a purplish nipple. Everything appeared neatly arranged, betraying the murderer’s grisly calm. Even the heat Andrew now noticed suffusing the room, suggested the ghoul had taken the time to light a nice fire in order to work in more comfort.

Andrew closed his eyes: he had seen enough. He did not want to know any more. Besides showing him how cruel and indifferent man could be towards his fellow human beings, the atrocities he could commit, given enough opportunity, imagination and a sharp knife, the murderer had provided him with a shocking and brutal lesson in anatomy. For the very first time Andrew realised that life, real life, had no connection with the way people spent their days, whose lips they kissed, what medals were pinned to their breasts or the shoes they mended. Life, real life, went on soundlessly inside our bodies, flowed like an underwater stream, occurred like a silent miracle of which only surgeons and pathologists were aware – and perhaps that ruthless killer. They alone knew that, ultimately, there was no difference between Queen Victoria and the most wretched beggar in London: both were complex machines made up of bone, organs and tissue, whose fuel was the breath of God.

This is a detailed analysis of what Andrew experienced during those fleeting moments when he stood before Marie Kelly’s dead body, although this description makes it seem as if he were gazing at her for hours, which was what it felt like to him. Eventually guilt began to emerge through the haze of pain and disgust for he immediately held himself responsible for her death. It had been in his power to save her, but he had arrived too late. This was the price of his cowardice. He let out a cry of rage and impotence as he imagined his beloved being subjected to this butchery.

Suddenly it dawned on him that unless he wanted to be linked to the murder he must get out before someone saw him. It was even possible the murderer was still lurking outside, admiring his macabre handiwork from some dark corner, and would have no hesitation in adding another corpse to his collection. He gave Marie Kelly a farewell glance, unable to bring himself to touch her, and with a supreme effort of will forced himself to withdraw from the little room, leaving her there.

As though in a trance, he closed the door behind him, leaving everything as he had found it. He walked towards the exit to the flats, but was seized by intense nausea and only just made it to the stone archway. There, half kneeling, he vomited, retching violently. After he had brought up everything, which was little more than the alcohol he had drunk that night, he leaned back against the wall, his body limp, cold and weak. From where he was, he could see the little room, number thirteen, the paradise where he had been so happy, now hiding his beloved’s dismembered corpse from the night. He took a few steps and, confident that his dizzy spell had eased sufficiently for him to walk, staggered out into Dorset Street.

Too distressed to get his bearings, he wandered aimlessly, letting out cries and sobs. He did not even attempt to find the carriage: now that he knew he was no longer welcome in his family home there was nowhere for him to tell Harold to go. He trudged along street after street, guided only by the forward movement of his feet. When he calculated he was no longer in Whitechapel, he looked for a lonely alley and collapsed, exhausted and trembling, in the midst of a pile of discarded boxes. There, curled up, he waited for night to pass.

As I predicted above, when the shock began to subside, his pain increased. His sorrow intensified until it became physical torment. Suddenly it was agony to be in his body, as if he lay in a sarcophagus lined with nails. He wanted to flee, unshackle himself from the excruciating substance he was made of, but he was trapped inside that martyred flesh. Terrified, he wondered if he would have to live with the pain for ever. He had read somewhere that the last image people see before they die is engraved on their eyes. Had the Ripper’s savage leer been etched on Marie Kelly’s pupils? He could not say, but he knew that if the rule were true he would be the exception: whatever else he might see before he died, his eyes would always reflect Marie Kelly’s mutilated face.

Without the desire or strength to do anything, Andrew let the hours slip by. Occasionally, he raised his head from his hands and let out a howl of rage to show the world his bitterness about all that had happened, which he was now powerless to change. He hurled random insults at the Ripper, who had conceivably followed him and was waiting, knife in hand, at the entrance to the alley. Then he laughed at his fear. For the most part, though, he wailed pitifully, oblivious to his surroundings, hopelessly alone with his own horror.

The arrival of dawn, leisurely sweeping away the darkness, restored his sanity somewhat. Sounds of life reached him from the entrance to the alley. He stood up with difficulty, shivering in his servant’s threadbare jacket, and walked out into the street, which was surprisingly lively.

Noticing the flags hanging from the fronts of the buildings, Andrew realised it was Lord Mayor’s Day. Walking as upright as he could, he joined the crowd. His grubby attire drew no more attention than that of any ordinary tramp. He had no notion of where he was, but that did not matter, since he had nowhere to go and nothing to do. The first tavern he came to seemed as good a destination as any. It was better than being swept along on the human tide making its way to the Law Courts to watch the arrival of the new mayor, James Whitehead. The alcohol would warm his insides, and at the same time blur his thoughts until they were no longer a danger to him.

The seedy public house was half empty. A strong smell of sausages and bacon coming from the kitchen made his stomach churn and he secluded himself in the corner furthest from the stoves and ordered a bottle of wine. He was forced to place a handful of coins on the table in order to persuade the man to serve him. While he waited, he glanced at the other customers, reduced to a couple of regular patrons, drinking in silence, oblivious to the clamour in the streets outside. One of them stared back at him, and Andrew felt a flash of sheer terror. Could he be the Ripper? Had he followed him there? He calmed down when he realised the man was too small to be a threat to anyone, but his hand was still shaking when he reached for the wine bottle. He knew now what man was capable of, any man, even the little fellow peacefully sipping his ale. He probably did not have the talent to paint the Sistine Chapel, but what Andrew could not be sure of was whether he was capable of ripping a person’s guts out and arranging their entrails around their body.

He gazed out of the window. People were coming and going, carrying on their lives without the slightest token of respect. Why did they not notice that the world had changed, that it was no longer habitable? Andrew gave a deep sigh. The world had changed only for him. He leaned back in his seat and applied himself to getting drunk. After that he would see. He glanced at the pile of money. He calculated he had enough to purchase every last drop of alcohol in the place, and so, for the time being, any other plan could wait. Sprawled over the bench, trying hard to prevent his mind from elaborating the simplest thought, Andrew let the day go by, his numbness increasing as he drew closer to the edge of oblivion.

But he was not too dazed to respond to the cry of a newspaper vendor. ‘Read all about it in the Star] Special edition: Jack the Ripper caught!’

Andrew leaped to his feet. The Ripper caught? He could hardly believe his ears. He leaned out of the window and, screwing up his eyes, scoured the street until he glimpsed a boy selling newspapers on a corner. He beckoned him over and bought a copy from him through the window. With trembling hands, he cleared away several bottles and spread the newspaper on the table. He had not misheard. ‘Jack the Ripper Caught!’ the headline declared. Reading the article proved slow and frustrating, due to his drunken state, but with patience and much blinking, he managed to decipher what was written.

The article began by declaring that Jack the Ripper had committed his last ever crime the previous night. His victim was a prostitute of Welsh origin called Marie Jeanette Kelly, discovered in the room she rented in Miller’s Court, at number twenty-six Dorset Street. Andrew skipped the following paragraph, which listed in gory detail the gruesome mutilations the murderer had perpetrated on her, and went straight to the description of his capture.

The newspaper stated that less than an hour after he had committed the heinous crime, the murderer who had terrorised the East End for four months had been caught by George Lusk and his men. Apparently, a witness who preferred to remain anonymous had heard Marie Kelly’s screams and alerted the Vigilance Committee. Unhappily, they reached Miller’s Court too late, but had managed to corner the Ripper as he fled down Middlesex Street. At first, the murderer tried to deny his guilt, but soon gave up after he was searched and the still warm heart of his victim was found in one of his pockets. The man’s name was Bryan Reese, and he worked as a cook on a merchant vessel, the Slip, which had docked at the Port of London from Barbados the previous July and would be setting sail for the Caribbean the following week.

During his interrogation by Frederick Abberline, the detective in charge of the investigation, Reese had confessed to the five murders of which he was accused, and had even shown his satisfaction at having been able to execute his final bloody act in the privacy of a room with a nice warm fire. He was tired of always having to kill in the street. ‘I knew I was going to follow that whore the moment I saw her,’ the murderer had gloated, before going on to claim he had murdered his own mother, a prostitute like his victims, as soon as he was old enough to wield a knife. This detail, which might have explained his behaviour, had yet to be confirmed.

Accompanying the article was a photogravure of the murderer so that Andrew could finally see the face of the man he had bumped into in the gloom of Hanbury Street. His appearance was disappointing. He was an ordinary-looking fellow, rather heavily built, with curly sideburns and a bushy moustache that drooped over his top Up. Despite his rather sinister smirk, which probably owed more to the conditions in which he had been photographed than anything else, Andrew had to admit he might just as well have been an honest baker as a ruthless killer. He certainly had none of the gruesome features Londoners’ imaginations had ascribed to him.

The following pages gave other related news items, such as the resignation of Sir Charles Warren following his acknowledgement of police incompetence in the case, or statements from Reese’s astonished fellow seamen on the cargo vessel, but Andrew already knew everything he wanted to know and went back to the front page. From what he could work out, he had entered Marie Kelly’s little room moments after the murderer had left and shortly before Lusk’s mob arrived, as if they were all keeping to a series of dance steps. He hated to think what would have happened had he delayed fleeing any longer and been discovered standing over Marie Kelly’s body by the Vigilance Committee. He had been lucky, he told himself.

He tore out the first page, folded it and put it into his jacket pocket, then ordered another bottle to celebrate that, although his heart was irreparably broken, he had escaped being beaten to a pulp by an angry mob.

Eight years later, Andrew took that same cutting from his pocket. Like him, it was yellowed with age. How often had he re-read it, recalling Marie Kelly’s horrific mutilations like a self-imposed penance? He had almost no other memories of the intervening years. What had he done during that time? It was difficult to say. He vaguely remembered Harold taking him home after scouring the various pubs in the vicinity and finding him passed out in that den. He had spent several days in bed with a fever, ranting and suffering from nightmares in which Marie Kelly’s corpse lay stretched out on her bed, her insides strewn about the room, or in which he was slitting her open with a huge knife while Reese looked on approvingly.

In a brief moment of clarity during his feverish haze, he was able to make out his father sitting stiffly on the edge of his bed, begging forgiveness for his behaviour. But it was easy to apologise now there was nothing to accept. Now all he had to do was join in the theatrical display of grief that the family, even Harold, had decided to put on for him as a mark of respect. Andrew waved his father away, with an impatient gesture that, to his annoyance, the proud William Harrington took to be absolution, judging from his smile of satisfaction as he left the room, as though he had sealed a successful deal. William Harrington had wanted to clear his conscience and that was what he had done, whether his son liked it or not. Now he could forget the matter and get back to business. Andrew did not really care: he and his father had never seen eye to eye and were not likely to do so now.

He recovered from his fever too late to attend Marie Kelly’s funeral, but not her killer’s execution. The Ripper was hanged at Wandsworth Prison, despite the objections of several doctors, who maintained Reese’s brain was worthy of scientific study: its bumps and folds must contain the crimes he had been predestined to commit since birth and should be recorded. Andrew watched as the executioner snuffed out Reese’s life but this did not bring back Marie Kelly’s or those of her fellow whores. Things did not work like that; the Creator knew nothing of bartering, only of retribution. At most, a child might have been born at the moment when the rope snapped the Ripper’s neck, but bringing back the dead to life was another matter. Perhaps that explained why so many had begun to doubt His power and even to question whether it was really He who had created the world.

That same afternoon, a spark from a lamp set alight the portrait of Marie Kelly hanging in the Winslows’ library. That, at least, was what Charles said – he had arrived just in time to put out the fire.

Andrew was grateful for Charles’s gesture, but the affair could not be ended by removing the cause. No, it was something that was impossible to deny. Thanks to his father’s generosity, Andrew got back his old life, but being reinstated as heir to the vast fortune his father and brother continued to amass meant nothing to him now. All that money could not heal the wound inside, although he soon realised that spending it in the opium dens of Poland Street helped. Too much drink had made him immune to alcohol, but opium was a far more effective and gentler aid to forgetting. Not for nothing had the ancient Greeks used it to treat a wide range of afflictions.

Andrew began to spend his days in the opium den, sucking his pipe as he lay on one of the hundreds of mattresses screened off by exotic curtains. In those rooms, lined with fly-blown mirrors that made their dimensions seem uncertain in the dim light cast by the gas lamps, Andrew fled his pain in the labyrinths of a shadowy, never-ending daydream. From time to time a skinny Malay filled his pipe bowl for him, until Harold or his cousin pulled back the curtain and led him out. If Coleridge had resorted to opium to alleviate the trifling pain of toothache, why should Andrew not use it to dull the agony of a broken heart, he replied, when Charles warned him of the dangers of addiction. As always his cousin was right, and although as his suffering abated Andrew stopped visiting the opium den, for a while he was obliged to carry phials of laudanum around with him.

That period lasted two or three years, until the pain finally disappeared, giving way to something far worse: emptiness, lethargy, numbness. Marie Kelly’s murder had obliterated his will to live, severed his unique communication with the world, leaving him deaf and dumb, manoeuvring him into a corner of the universe where nothing happened. He had turned into an automaton, a gloomy creature that lived out of habit, without hope, simply because life, real life, had no link to the way he spent his days, but occurred quietly inside him, like a silent miracle, whether he liked it or not. In short, he became a lost soul, shutting himself in his room by day and roaming Hyde Park by night. Even the action of a flower coming into bud seemed rash, futile and pointless.

In the meantime, his cousin Charles had married one of the Keller sisters – Victoria or Madeleine, Andrew could not remember which – and had purchased an elegant house in Elystan Street. This did not stop him visiting Andrew nearly every day, and occasionally dragging him to his favourite brothels on the off-chance that one of the new girls might have the fire between her legs to rekindle his cousin’s dulled spirit. But to no avail: Andrew refused to be pulled out of the hole into which he had dug himself.

To Charles – whose point of view I shall adopt at this juncture, if you will consent to this rather obvious switch of perspective within a paragraph – this showed the resignation of someone who has embraced the role of victim. After all, the world needed martyrs as evidence of the Creator’s cruelly. It was even conceivable that his cousin had come to view what had happened to him as an opportunity to search his soul, to venture into its darkest, most inhospitable regions.

How many people go through life without experiencing pure pain? Andrew had known complete happiness and utter torment; he had used up his soul, so to speak, exhausted it completely. And now, comfortably installed with his pain, like a fakir on a bed of nails, he seemed to await who knew what: perhaps the applause signalling the end of the performance. Charles was certain that if his cousin was still alive it was because he felt compelled to experience that pain to the hilt. It was irrelevant whether this was a practical study of suffering or to atone for his guilt. Once Andrew felt he had achieved this, he would take a last bow and leave the stage for good.

Thus, each time Charles visited the Harrington mansion and found his cousin prone but still breathing, he heaved a sigh of relief. And when he arrived home empty-handed, convinced that anything he could do for Andrew was useless, he reflected on how strange life could be, how flimsy and unpredictable it was if it could be altered so drastically by the mere purchase of a painting. Was it within his power to change his cousin’s life again? Could he alter the path it would take before it was too late? He did not know. The only thing he was certain of was that, given everyone else’s indifference, he had to try.

In the little room on Dorset Street, Andrew opened the cutting and read for the last time, as though it were a prayer, the account of Marie Kelly’s mutilations. Then he folded it and replaced it in his coat pocket. He contemplated the bed, which bore no trace of what had happened there eight years before. But that was the only thing that was different: everything else remained unchanged – the grimy mirror, in which the crime had been immortalised, Marie Kelly’s little perfume bottles, the cupboard where her clothes still hung, even the ashes in the hearth left from the fire the Ripper had lit to make slitting her open cosier. He could think of no better place to take his own life.

He placed the barrel of the revolver under his jaw and crooked his finger around the trigger. Those walls would be splattered with blood once more, and far away, on the distant moon, his soul would at last take up its place in the little hollow awaiting him in Marie Kelly’s bed.