По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

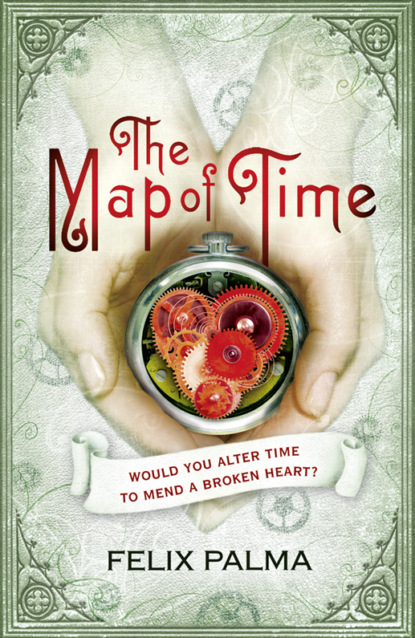

The Map of Time and The Turn of the Screw

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter VI

With the revolver barrel digging into the flesh beneath his jaw, and his finger poised on the trigger, Andrew thought how strange it was for him to have come to this. He had chosen to bring about his own death even though most of his life he had, like everyone else, been content merely to fear it, imagine it in every illness, see it lurking treacherously all around him in a world of precipices, sharp objects, thin ice and jumpy horses, mocking the fragility of those who claimed to be kings of Creation. All that worrying about death, he thought, only to embrace it now. But that was how things were: it was enough to find life a sterile, unrewarding exercise to want to end it, and there was only one way to do that. And he had to confess that the vague unease he felt was in no way existential. Dying itself did not worry him in the least, because fear of death, whether it was a bridge to a biblical universe or a plank artfully suspended above the void, always derived from the certainly that the world went on without us, like a dog after its ticks have been removed.

Broadly speaking, then, pulling the trigger meant pulling out of the game, relinquishing any possibility of being dealt a better hand in the next round. Andrew doubted this could happen. He had lost all faith. He did not believe fate had any reward in store for him that would make up for the pain he had suffered. He did not believe such recompense existed. He was afraid of something far more mundane: the pain he would doubtless feel when the bullet shattered his jaw. Naturally, it would not be pleasant, but it was part of his plan, and therefore something he must accept. He felt his finger grow heavy as it rested on the trigger, gritted his teeth and prepared to put an end to his tragic life.

Just then, a knock came on the door. Startled, Andrew opened his eyes. Who could this be? Had McCarthy seen him arrive and come to ask for money to fix the window? The knocking became more insistent. That accursed money-grubber! If the man had the gall to stick his snout through the hole in the window, Andrew would not hesitate to shoot him. What did it matter now if he broke the absurd commandment about not killing your fellow man, especially if that man happened to be McCarthy?

‘Andrew, I know you’re in there. Open the door.’

With a bitter grimace, Andrew recognised his cousin Charles’s voice. Charles, Charles – always following him everywhere, looking out for him. He would have preferred it to be McCarthy. He could not shoot Charles. How had his cousin found him? And why did he go on trying when Andrew himself had long since given up?

‘Go away, Charles, I’m busy’ he cried.

‘Don’t do it, Andrew! I’ve found a way of saving Marie!’

‘Saving Marie?’ Andrew laughed grimly. He had to admit his cousin had imagination, although this was verging on bad taste. ‘Perhaps I should remind you Marie is dead,’ he shouted. ‘She was murdered in this miserable room eight years ago. When I could have saved her I didn’t. How can we save her now, Charles? By travelling through time?’

‘Exactly’ his cousin replied, slipping something beneath the door.

Andrew glanced at it with vague curiosity. It looked like a leaflet.

‘Read it, Andrew,’ his cousin implored, through the broken window. ‘Please read it.’

Andrew felt rather ashamed that his cousin should see him with the revolver pressed ridiculously against his jaw – perhaps not the most suitable place if you wanted to blow your head off. Knowing his cousin would not go away, he lowered the gun with an exasperated sigh, placed it on the bed and rose to fetch the piece of paper.

‘All right, Charles, you win,’ he muttered. ‘Let’s see what this is about’

He picked up the sheet of paper and examined it. It was a faded sky-blue handbill. He read it, unable to believe that what it said could be true. Amazing though it seemed, he was holding the advertisement for a company called Murray’s Time Travel, which offered journeys through time. This was what it said:

Tired of travelling through space?

Now you can travel through time, into the fourth dimension.

Make the most of our special opening offer and journey to the year 2000. Witness an era only your grandchildren will live to see. Spend three whole hours in the year 2000 for a mere one hundred pounds. See with your own eyes the future war between automatons and humans that will change the fate of the world. Don’t be the last to hear about it.

The text was accompanied by an illustration intended to portray a fierce battle between two powerful armies. It showed a landscape of supposedly ruined buildings, a mound of rubble before which were ranged the two opposing sides. One was clearly human; the other consisted of humanoid creatures apparently made of metal. The drawing was too crude to make out anything more.

What on earth was this? Andrew felt he had no choice but to unlock the door. Charles walked in, closing it behind him. He stood breathing into his hands to warm them, but beaming contentedly at having intervened to stop his cousin’s suicide. For the time being, at least. The first thing he did was seize the pistol from the bed.

‘How did you know I was here?’ asked Andrew, while his cousin posed in front of the mirror waving the gun about furiously.

‘You disappoint me, cousin,’ replied Charles, emptying the bullets from the chamber into his cupped hand and depositing them in his coat pocket. ‘Your father’s gun cabinet was open, a pistol was missing, and today is the seventh of November. Where else would I have gone to look for you? You may as well have left a trail of breadcrumbs.’

‘I suppose so,’ conceded Andrew. His cousin was right. He had not gone out of his way to cover his tracks.

Charles held the pistol by its barrel and handed it to Andrew. ‘Here you are. You can shoot yourself as many times as you like now’

Andrew snatched the gun and stuffed it into his pocket, eager to make the embarrassing object disappear. He would just have to kill himself some other time. Charles looked at him with mock-disapproval, waiting for some sort of explanation, but Andrew did not have the energy to convince him that suicide was the only solution he could envisage. Before his cousin had the chance to lecture him, he decided to side-step the issue by enquiring about the leaflet.

‘What’s this? Some kind of joke?’ he asked, waving the piece of paper in the air. ‘Where did you have it printed?’

Charles shook his head. ‘It’s no joke, cousin. Murray’s Time Travel is a real company. The main offices are in Greek Street in Soho. And, as the advertisement says, they offer the chance to travel through time.’

‘But, is that possible?’ stammered Andrew, taken aback.

‘It certainly is,’ replied Charles, completely straight-faced. ‘What’s more, I’ve done it myself.’ They stared at one another for a moment.

‘I don’t believe you,’ said Andrew at last, trying to detect a hint in his cousin’s solemn face that would give the game away, but Charles shrugged.

‘I’m telling the truth,’ he assured him. ‘Last week, Madeleine and I travelled to the year 2000.’

Andrew burst out laughing, but his cousin’s earnest expression silenced his guffaws. ‘You’re not joking, are you?’

‘No, not at all,’ Charles replied. ‘Although I can’t say I was all that impressed. The year 2000 is a dirty, cold year where man is at war with machines. But not seeing it is like missing a new opera that’s all the rage.’

Andrew listened, still stunned.

‘It’s a unique experience,’ his cousin added. ‘If you think about it, it’s exciting because of all it implies. Madeleine has even recommended it to her friends. She fell in love with the human soldiers’ boots. She tried to buy me a pair in Paris, but couldn’t find any. I suspect it’s too soon yet.’

Andrew reread the leaflet to make sure he was not imagining things. ‘I still can’t believe …’ he stammered.

‘I know, cousin, I know. But, you see, while you’ve been roaming Hyde Park like a lost soul the world has moved on. Time goes by even when you’re not watching it. And, believe me, strange as it may seem to you, time travel has been the talk of all the salons, the favoured topic of discussion, since the novel that gave rise to it came out last spring.’

‘A novel?’ asked Andrew, increasingly bewildered.

‘Yes. The Time Machine by H. G. Wells. It was one of the books I lent you. Didn’t you read it?’

Since Andrew had shut himself away in the house, refusing to go along with Charles on those outings to taverns and brothels, his cousin had started bringing him books. They were usually new works by unknown authors, inspired by the century’s craze for science to write about machines capable of performing the most elaborate miracles. The stories were known as ‘scientific romances’ – the English publishers’ translation of Jules Verne’s ‘extraordinary voyages’, an expression that had taken hold with amazing rapidity and was used to describe any fantasy novel that tried to explain itself by using science. According to Charles, these novels captured the spirit that had inspired the works of Bergerac and Samosata, and had taken over from the old tales of haunted castles.

Andrew remembered some of the madcap inventions in those tales, such as the anti-nightmare helmet hooked up to a tiny steam engine that sucked out bad dreams and turned them into pleasant ones. But the one he remembered best was the machine that made things grow, invented by a Jewish scientist who used it on insects: the image of London attacked by a swarm of flies the size of airships, crushing towers and flattening buildings as they landed on them, was ridiculously terrifying. There had been a time when Andrew would have devoured such books but, much as he regretted it, the worlds of fiction were not exempt from his steadfast indifference to life: he did not want any type of balm but to stare straight into the gaping abyss, thus making it impossible for Charles to reach him via the secret passage of literature. Andrew assumed that this fellow Wells’s book must be buried at the bottom of his chest, under a mound of similar novels he had scarcely glanced at.

When Charles saw the empty look on his cousin’s face he gestured to him to sit back down in his chair and drew up the other. Leaning forward slightly, like a priest about to take confession from one of his parishioners, he began summarising the plot of the novel that, according to him, had revolutionised England. Andrew listened sceptically. As he could guess from the title, the main character was a scientist who had invented a time machine that allowed him to journey through the centuries. All he had to do was pull on a little lever and he was propelled at great speed into the future, gazing in awe as snails ran like hares, trees sprouted from the ground like geysers, the stars circled in the sky, which changed from day to night in a second … This wild and wonderful journey took him to the year 802,701, where he discovered that society had split into two different races: the beautiful and useless Eloi and the monstrous Morlocks, creatures that lived underground, feeding off their neighbours up above, whom they bred like cattle.

Andrew bridled at this description, making his cousin smile, but Charles quickly added that the plot was unimportant, no more than an excuse to create a flimsy caricature of the society of their time. What had shaken the English imagination was that Wells had envisaged time as a fourth dimension, transforming it into a sort of magic tunnel you could travel through.

‘We are all aware that objects possess three dimensions – length, breadth and thickness,’ explained Charles. ‘But in order for this object to exist,’ he went on, picking up his hat and twirling it in his hands like a conjuror, ‘in order for it to form part of this reality we find ourselves in, it needs duration in time as well as in space. That is what enables us to see it, and prevents it disappearing before our very eyes. We live, then, in a four-dimensional world. If we accept that time is another dimension, what is to stop us moving through it? In fact, that’s what we are doing. Just like our hats, you and I are moving forwards in time, albeit in a tediously linear fashion, without leaving out a single second, towards our inexorable end. What Wells is asking in his novel is why we can’t speed up this journey, or even turn around and travel backwards to that place we refer to as the past – which, ultimately, is no more than a loose thread in the skein of our lives. If time is a spatial dimension, what prevents us moving around in it as freely as we do in the other three?’

Pleased with his explanation, Charles replaced his hat on the bed. Then he studied Andrew, allowing him a moment to assimilate what he had just said.

‘I must confess when I read the novel I thought it was rather an ingenious way of making what was basically a fantasy believable,’ he went on, a moment later, when his cousin said nothing, ‘but I never imagined it would be scientifically achievable. The book was a raging success, Andrew, people spoke of nothing else in the clubs, the salons, the universities, during factory breaks. Nobody talked any more about the crisis in the United States and how it might affect England, or Waterhouse’s paintings or Oscar Wilde’s plays. The only thing people were interested in was whether time travel was possible or not. Even the women’s suffrage movement was fascinated by the subject and interrupted their regular meetings to discuss it. Speculating about what tomorrow’s world would be like or discussing which past events ought to be changed became England’s favourite pastime, the quickest way to liven up conversation during afternoon tea.

‘Naturally such discussions were futile, because nobody could reach any enlightened conclusions, except in scientific circles, where an even more heated debate took place, whose progress was reported almost daily in the national newspapers. But nobody could deny it was Wells’s novel that had sparked off people’s yearning to journey into the future, to go beyond the bounds imposed on them by their fragile, destructible bodies. Everybody wanted to glimpse the future, and the year 2000 became the most logical objective, the year everyone wanted to see. A century was easily enough time for everything to be invented that could be invented, and for the world to have been transformed into a marvellously unrecognisable, magical, possibly even a better place.

‘Ultimately, this all seemed to be no more than a harmless amusement, a naïve desire – that is, until last October, when Murray’s Time Travel opened for business. This was announced with great fanfare in the newspapers and on publicity posters. Gilliam Murray could make our dreams come true. He could take us to the year 2000. Despite the cost of the tickets, huge queues formed around his building. I saw people who had always maintained that time travel was impossible waiting like excited children for the doors to open. Nobody wanted to pass up this opportunity. Madeleine and I couldn’t get seats for the first expedition, only the second. And we travelled in time, Andrew. Believe it or not, I have been a hundred and five years into the future and returned. This coat still has traces of ash on it. It smells of the war of the future. I even picked up a piece of rubble from the ground when no one was looking, a rock we have displayed in the drawing-room cabinet, a replica of which must still be intact in some building in London.’

Andrew felt like a boat spinning in a whirlpool. It seemed incredible to him that it was possible to travel in time, not to be condemned to see only the era he was born into, the period that lasted as long as his heart and body held out, but to be able to visit other eras, other times where he did not belong, leap-frogging his own death, the tangled web of his descendants, desecrating the sanctuary of the future, journeying to places hitherto only dreamed of or imagined. For the first time in years he felt a flicker of interest in something beyond the wall of indifference with which he had surrounded himself.

He immediately forced himself to snuff out the flame before it became a blaze. He was in mourning, a man with an empty heart and a dormant soul, a creature devoid of emotion, the perfect example of a human being who had felt everything there was for him to feel. He had nothing in the whole wide world to live for. He could not live, not without her.