По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

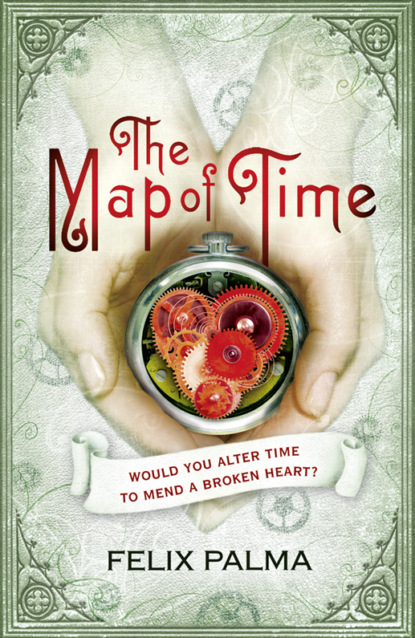

The Map of Time and The Turn of the Screw

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That’s remarkable, Charles.’ He sighed wearily, feigning indifference to these unnatural journeys. ‘But what has this to do with Marie?’

‘Don’t you see, cousin?’ Charles replied, in an almost scandalised tone. ‘This man Murray can travel into the future. No doubt if you offered him enough money he could organise a private tour for you into the past. Then you’d really have someone to shoot’

Andrew’s jaw dropped. ‘The Ripper?’ he said, his voice cracking.

‘Exactly’ replied Charles. ‘If you travel back in time you can save Marie.’

Andrew gripped the chair to stop himself falling off it. Was it possible? Could he really travel back in time to the night of 7 November 1888 and save Marie? The possibility that this might be true made him feel giddy not just because of the miracle of travelling through time, but because he would be going back to a period when she was still alive: he would be able to hold in his arms the body he had seen cut to ribbons. But what moved him most was that someone should offer him the chance to save her, to put right his mistake, to change a situation it had taken him all these years to learn to accept as irreversible. He had always prayed to the Creator to be able to do that. It seemed he had been calling upon the wrong person. This was the age of science.

‘What do you say, Andrew? We have nothing to lose by trying,’ he heard his cousin remark.

Andrew stared at the floor, struggling to put some order into the tumult of emotions he felt. He did not really believe it was possible, and yet if it was, how could he refuse to try? This was the chance for which he had waited eight years. He raised his head and gazed at his cousin, shaken. ‘All right,’ he said in a hoarse whisper.

‘Excellent, Andrew,’ said Charles, overjoyed, and clapped him on the back. ‘Excellent’

His cousin smiled unconvincingly then looked down at his shoes again: he was going to travel back to his old haunts, to relive moments already past, back to his own memories.

‘Well,’ said Charles, glancing at his pocket watch. ‘We’d better have something to eat. I don’t think travelling back in time on an empty stomach is a good idea.’

They left the little room and made their way to Charles’s carriage, which was waiting by the stone archway. They followed the same routine that night as though it were no different from any other. They dined at the Café Royal, which served Charles’s favourite steak and kidney pie, let off steam at Madame Norrell’s brothel, where Charles liked to try out the new girls while they were still fresh, and ended up drinking until dawn in the bar at Claridge’s, where Charles rated the champagne list above any other.

Before their minds became too clouded by drink, Charles explained to Andrew that he had journeyed into the future on a huge tramcar, the Cronotilus, which was propelled through the centuries by an impressive steam engine. But Andrew was incapable of showing any interest in the future: his mind was taken up with imagining what it would be like to travel in the exact opposite direction, into the past. There, his cousin had assured him, he would be able to save Marie by confronting the Ripper.

Over the past eight years, Andrew had built up feelings of intense rage towards that monster. Now he would have the chance to vent them. However, it was one thing to threaten a man who had already been executed, quite another to confront him in the flesh, in the sort of sparring match Murray would set up for him. Andrew gripped the pistol, which he had kept in his pocket, as he recalled the burly man he had bumped into in Hanbury Street, and tried to cheer himself with the thought that, although he had never shot a real person before, he had practised his aim on bottles, pigeons and rabbits. If he remained calm, everything would go well. He would aim at the Ripper’s heart or his head, let off a few shots calmly, and watch him die a second time. Yes, that was what he would do. Only this time, as though someone had tightened a bolt in the machinery of the universe to make it function more smoothly, the Ripper’s death would bring Marie Kelly back to life.

Chapter VII

Although it was early morning, Soho was already teeming with people. Charles and Andrew had to push their way through the crowded streets, full of men in bowlers and women wearing hats adorned with plumes and even the odd dead bird. Couples strolled along the pavements arm in arm, sauntered in and out of shops, or stood waiting to cross the streets, along which moved, as slowly as lava, a torrent of luxurious carriages, cabriolets, trams and carts carrying barrels, fruit, or mysterious shapes covered with tarpaulins, possibly bodies robbed from the graveyard. Scruffy second-rate artists, performers and acrobats displayed their dubious talents on street corners in the hope of attracting the attention of some passing promoter.

Charles had not stopped chattering since breakfast, but Andrew could hardly hear him above the loud clatter of wheels on the cobbles and the piercing cries of vendors. He was content to let his cousin guide him through the grey morning, immersed in a sort of stupor from which he was roused only by the sweet scent of violets as they passed one of many flower-sellers with fragrant baskets.

The moment they entered Greek Street, they spotted the modest building where the offices of Murray’s Time Travel were situated. It was an old theatre that had been remodelled by its new owner, who had not hesitated to blight the neo-classical façade with a variety of ornamentation that alluded to time. At the entrance, a flight of steps, flanked by two columns, led up to an elegant, sculpted wooden door crowned by a pediment decorated with a carving of Chronos spinning the wheel of the zodiac. The god of time, depicted as a sinister old man with a flowing beard reaching to his navel, was bordered by a frieze of carved hourglasses, a motif repeated on the arches above the tall windows on the second floor. Between the pediment and the lintel, ostentatious pink marble lettering announced that this picturesque edifice was the head office of Murray’s Time Travel.

Charles and Andrew noticed passers-by stepping off the section of pavement outside the unusual building. As they drew closer, they understood why. A nauseating odour made them screw up their faces in disgust and invited them to regurgitate the breakfast they had just eaten. The cause of the stench was a viscous substance, which a couple of workmen, masked with neckerchiefs, were vigorously washing off part of the façade with the aid of brushes and pails of water. As the brushes made contact with the dark substance, it slopped on to the pavement, transformed into a revolting black slime.

‘Sorry about the inconvenience, gents,’ one of the workmen said, pulling down his neckerchief. ‘Some louse smeared cow dung all over the front of the building, but we’ll soon have it cleaned off.’

Exchanging puzzled looks, Andrew and Charles pulled out their handkerchiefs and, covering their faces like highwaymen, hurried through the front door. In the hallway, the evil smell was being kept at bay by rows of strategically placed vases of gladioli and roses. Just as on the outside of the building, the interior was filled with a profusion of objects whose theme was time. The central area was taken up by a gigantic mechanical sculpture consisting of an enormous pedestal out of which two articulated spider-like arms stretched towards the shadowy ceiling. They were clutching an hourglass the size of a calf embossed with iron rivets and bands. It contained not sand but a sort of blue sawdust that flowed gracefully from one section to the other and even gave off a faint, evocative sparkle when caught by the light from the nearby lamps. Once the contents had emptied into the lower receptacle, the arms turned the hourglass by means of some complex hidden mechanism, so that the artificial sand never ceased to flow, a reminder of time itself.

Alongside the colossal structure there were many other remarkable objects. Although less spectacular, they were more noteworthy for having been invented many centuries before, like the bracket clocks bristling with levers and cogs that stood silently at the back: according to the plaques on their bases, they were early efforts at mechanical timepieces. The walls were lined with hundreds of clocks, from the traditional Dutch stoelklok, adorned with mermaids and cherubs, to Austro-Hungarian examples with seconds pendulums. The air was filled with a relentless ticking, which must have become an endless accompaniment to the lives of those who worked in the building and without whose comforting presence they doubtless felt bereft on Sundays.

A young woman stood up from her desk in the corner and came over to Andrew and Charles. She walked with the grace of a rodent, her steps following the rhythm of the insistent ticking. After greeting them courteously, she informed them excitedly that there were still a few tickets left for the third expedition to the year 2000 and that they could make a reservation if they wished. Charles refused her offer with a dazzling smile, telling her they were there to see Gilliam Murray. The woman hesitated briefly, then informed them that he was in the building and, although he was a very busy man, she would do her best to arrange for them to meet him. Charles showed his appreciation of this with an even more captivating smile. Once she had managed to tear her eyes away from his perfect teeth, she wheeled round and gestured to them to follow her.

At the far end of the vast hall a marble staircase led to the upper floors. She guided the cousins down a long corridor lined with tapestries depicting various scenes from the war of the future. Naturally, the corridor, too, was replete with the obligatory clocks, hanging on the walls and standing on dressers or shelves, filling the air with their ubiquitous ticking. When they reached Murray’s ostentatious office door, the woman asked them to wait outside, but Charles ignored her request and followed her in, dragging his cousin behind him.

The gigantic proportions of the room surprised Andrew, as did the clutter of furniture and the numerous maps lining the walls. He was reminded of the campaign tents from which field marshals orchestrated wars. They had to glance around the room several times before they discovered Gilliam Murray, lying stretched out on a rug, playing with a dog.

‘Good day, Mr Murray’ said Charles, before the secretary had a chance to speak. ‘My name is Charles Winslow and this is my cousin, Andrew Harrington. We would like a word with you, if you are not too busy’

Gilliam Murray, a strapping fellow in a garish purple suit, accepted the thrust sportingly but with the enigmatic expression of a man who holds a great many aces up his sleeve, which he has every intention of pulling out at the first opportunity. ‘I always have time for two such illustrious gentlemen as yourselves,’ he said, picking himself up.

When he had risen to his full height, Andrew and Charles could see that Gilliam Murray seemed to have been magnified by some kind of spell. Everything about him was oversized, from his hands, which appeared capable of wrestling a bull to the ground by its horns, to his head, which looked more suited to a Minotaur. However, he moved with extraordinary, even graceful, agility. His straw-coloured hair was combed carefully back, and the smouldering intensity of his big blue eyes betrayed an ambitious, proud spirit, which he toned down with a friendly smile.

With a wave, he invited to them to follow him to his desk on the far side of the room. He led them along the trail he had forged between globes, tables piled with books, and notebooks strewn all over the floor. Andrew noticed there was no shortage of clocks there either. Besides those hanging from the walls and invading the bookcase, an enormous glass cabinet contained a collection of portable clocks, sundials, intricate water clocks and other artefacts showing the evolution of the display of time. It appeared to Andrew that presenting all these objects was Murray’s clever way of showing the absurdity of man’s vain attempts to capture an elusive, absolute, mysterious and indomitable force. With his colourful collection, he seemed to be saying that man’s only achievement was to strip time of its metaphysical essence, transforming it into a commonplace instrument for ensuring he did not arrive late to meetings.

Charles and Andrew lowered themselves into two plush Jacobean-style armchairs facing the majestic desk at which Murray sat, framed by an enormous window behind him. As the light streamed in through the leaded panes, suffusing the office with rustic cheer, it even occurred to Andrew that the entrepreneur had a sun all of his own, while everyone else was submerged in the dull morning light.

‘I hope you’ll forgive the unfortunate smell in the entrance,’ Murray said, with a grimace. ‘This is the second time someone has smeared excrement on the front of the building. Perhaps an organised group is attempting to disrupt the smooth running of our enterprise in this unpleasant way’ He shrugged his shoulders despairingly, as though to emphasise how upset he was about the matter. ‘As you can see, not everyone thinks time travel is a good thing for society. And yet society has been clamouring for it ever since Mr Wells’s wonderful novel came out. I can think of no other explanation for these acts of vandalism, as the perpetrators have not claimed responsibility or left any clues. They simply foul the front of our building.’

He stared into space for a moment, lost in thought. Then he appeared to rouse himself, sat upright and looked straight at his visitors. ‘But, tell me, gentlemen, what can I do for you?’

‘I would like you to organise a private journey back to the autumn of 1888, Mr Murray’ replied Andrew, who had been waiting impatiently for the giant to allow them to get a word in edgeways.

‘To the Autumn of Terror?’ asked Murray, taken aback.

‘Yes, to the night of November the seventh, to be precise.’

Murray studied him silently. Finally, without trying to conceal his annoyance, he opened one of the desk drawers and took out a bundle of papers tied with a ribbon. He set them on the desk wearily, as if he were showing them some tiresome burden he was compelled to suffer. ‘Do you know what this is, Mr Harrington?’ He sighed. ‘These are the letters we receive every day from private individuals. Some want to be taken to the hanging gardens of Babylon, others to meet Cleopatra, Galileo or Plato, still more to see with their own eyes the battle of Waterloo, the building of the Pyramids or Christ’s crucifixion. Everybody wants to go back to their favourite moment in history, as though it were as simple as giving an address to a coachman. They think the past is at our disposal. I am sure you have your reasons for wanting to travel to 1888, like those who wrote these requests, but I’m afraid I can’t help you.’

‘I only need to go back eight years, Mr Murray’ replied Andrew. ‘And I’ll pay anything you ask.’

‘This isn’t about distances in time or about money’ Murray scoffed. ‘If it were, Mr Harrington, I’m sure we could come to some arrangement. Let us say the problem is a technical one. We can’t travel anywhere we want in the past or the future.’

‘You mean you can only take us to the year 2000?’ exclaimed Charles, visibly disappointed.

‘I’m afraid so, Mr Winslow We hope to be able to extend our offer in the future. However, for the moment, as you can see from our advertisement, our only destination is May the twentieth, 2000, the exact day of the final battle between the evil Solomon’s automatons and the human army led by the brave Captain Shackleton. Wasn’t the trip exciting enough for you, Mr Winslow?’ he asked, with a flicker of irony, giving Charles to understand he did not forget easily the faces of those who had been on his expeditions.

‘Oh, yes, sir,’ Charles replied, after a brief pause. ‘Most exciting. Only I assumed—‘

‘You assumed we could travel in either direction along the time continuum,’ Murray interposed. ‘But I’m afraid we can’t. The past is beyond our competence.’ His face bore a look of genuine regret, as though he were weighing up the damage his words had done to his visitors. ‘The problem, gentlemen,’ he sighed, leaning back in his chair, ‘is that, unlike Wells’s character, we don’t travel through the time continuum. We travel outside it, across the surface of time, as it were.’

He fell silent, staring at them without blinking, with the serenity of a cat.

‘I don’t understand,’ Charles declared.

Gilliam Murray nodded, as though he had expected that reply. ‘Let me make a simple comparison: you can move from room to room inside a building, but you can also walk across its roof, can you not?’

Charles and Andrew nodded, somewhat put out by Murray’s seeming wish to treat them like a couple of foolish children.

‘Contrary to all appearances,’ their host went on, ‘it was not Wells’s novel that made me look into the possibilities of time travel. If you have read the book, you will understand that the author is simply throwing down the gauntlet to the scientific world by suggesting a direction for their research. Unlike Verne, he cleverly avoided any practical explanations of the workings of his invention, choosing instead to describe his machine to us using his formidable imagination – a perfectly valid approach, given the book is a work of fiction. However, until science proves such a contraption is possible, his machine will be nothing but a toy. Will that ever happen?

‘I’d like to think so: the achievements of science so far this century give me great cause for optimism. You will agree, gentlemen, we live in remarkable times. Times when man questions God daily. How many marvels has science produced over the past few years? Some, such as the calculating machine, the typewriter or the electric lift, have been invented simply to make our lives easier, but others cause us to feel powerful because they render the impossible possible. Thanks to the steam locomotive, we are now able to travel long distances without taking a single step, and soon we will be able to relay our voices to the other side of the country without having to move, like the Americans, who are already doing so with the so-called telephone.

‘There will always be people who oppose progress, who consider it a sacrilege for mankind to transcend his own limitations. Personally I believe science ennobles man, reaffirms his control over nature, in the same way that education or morality helps us overcome our primitive instincts. Take this marine chronometer, for example,’ he said, picking up a wooden box lying on the desk. ‘Today these are mass-produced and every ship in the world has one, but that wasn’t always the case. Although they may appear now always to have formed part of our lives, the Admiralty was obliged to offer a prize of twenty thousand pounds to the person who could invent a way of determining longitude at sea, because no clockmaker was capable of designing a chronometer that could withstand the rolling of a vessel without going wrong. The competition was won by a man called John Harrison, who devoted forty years of his life to solving this thorny scientific problem. He was nearly eighty when he finally received the prize money.

‘Fascinating, don’t you think? At the heart of each invention lie one man’s efforts, an entire life dedicated to solving a problem, to inventing an instrument that will outlast him, will go on forming part of the world after he is dead. So long as there are men who aren’t content to eat the fruit off the trees or to summon rain by beating a drum, but who are determined instead to use their brains in order to transcend the role of parasite in God’s creation, science will never give up trying.

‘That’s why I am sure that very soon, as well as being able to fly like birds in winged carriages, anyone will be able to get hold of a machine similar to the one Wells dreamed up, and travel anywhere they choose in time. Men of the future will lead double lives, working during the week in a bank, and on Sundays making love to the beautiful Nefertiti or helping Hannibal conquer Rome. Can you imagine how an invention like that would change society? ‘