По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

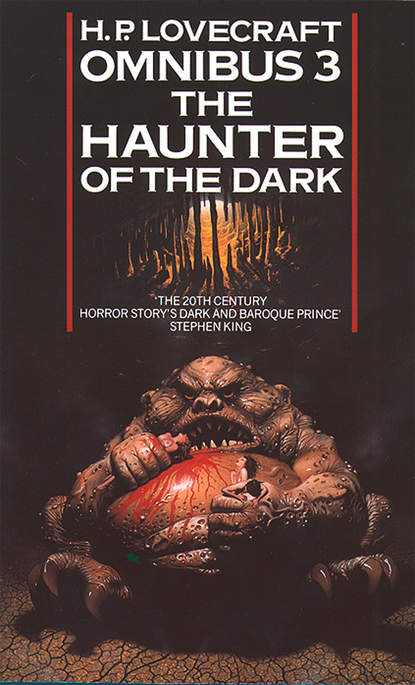

The Haunter of the Dark and Other Tales

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Haunter of the Dark and Other Tales

H. P. Lovecraft

A collection of some of the most famous stories from the master of tomb-dark fear…A collection of some of the most famous stories from the master of tomb-dark fear…

H. P. Lovecraft Omnibus

3

The Haunter of the Dark and Other Tales

H. P. Lovecraft

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ue756693a-3cc8-52a6-939b-8e3480864d98)

Title Page (#u8775de43-5388-59c2-b39d-16c09b8f246c)

An Introduction To H. P. Lovecraft (#u0493087b-d619-5144-9fde-f980d4e0037a)

The Outsider (#u8c0b7661-0f47-5da0-b9f5-dba39e433fad)

The Rats in the Walls (#ub82e98c9-3be3-5a5b-a23d-a5113d114880)

Pickman’s Model (#u187f0307-1bd2-59f3-bfc3-479bae4171c1)

The Call of Cthulhu (#u70c33caa-f459-5530-88f8-5376e71bed18)

The Dunwich Horror (#u043261d3-d158-5a7d-a0b4-7217b3e6fe80)

The Whisperer in Darkness (#litres_trial_promo)

The Colour Out of Space (#litres_trial_promo)

The Haunter of the Dark (#litres_trial_promo)

The Thing on the Doorstep (#litres_trial_promo)

The Music of Erich Zann (#litres_trial_promo)

The Lurking Fear (#litres_trial_promo)

The Picture in the House (#litres_trial_promo)

The Shadow Over Innsmouth (#litres_trial_promo)

The Shadow Out of Time (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

An Introduction To H. P. Lovecraft (#ulink_919c3a89-d940-5535-a418-69f57419d0da)

Despite the work of such writers as Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Ambrose Bierce, America has no macabre tradition in its literature. Poe and Bierce almost alone produced a considerable body of writing in the genre; Edith Wharton, Henry James, Mary E. Wilkins-Freeman, Robert W. Chambers and a handful of others who wrote in the domain of fantasy are associated primarily with writing that is not macabre. There is not in America a collection of prose in the genre of the fantastic comparable to that produced in England by such masters as Arthur Machen, Walter de la Mare, Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany, M. R. James, E. F. Benson, May Sinclair, Marjorie Bowen, A. E. Coppard, John Collier, H. R. Wakefield, Lady Cynthia Asquith, Thomas Burke, L. P. Hartley, John Metcalfe, Margery Lawrence, and others.

It is therefore all the more interesting to note that a new generation of writers in America has turned consistently towards fantasy as a medium of creative expression. Perhaps it was the lack of any adequate outlet which dampened the ardour of prospective writers before our own time; certainly American magazines and book publishers have long been aloofly cool towards prose and poetry of the supernatural or bizarre. But with the establishment in 1923 of the magazine Weird Tales, interest in fantasy received a new impetus, and there came into modest prominence a group of writers including Clark Ashton Smith, the Reverend Henry S. Whitehead, Frank Belknap Long, Carl Jacobi, Robert Bloch, Ray Bradbury, and, surely at the head of the list, the late H. P. Lovecraft.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft, who died at forty-seven in 1937, was a native of Providence, Rhode Island, where he was a devoted student of the antiquities of that city and, perhaps by natural inclination grown from his ancestry, throughout his life a pronounced Anglophile. He led a sheltered early life, since his health was uncertain, and his semi-invalidism enabled him to read omnivorously, as a result of which the sensitive, dreamy child he was early created a strange world of his own, peopled by the creatures of his fancy. Out of this world subsequently grew much of his fiction in the realm of the supernatural.

Lovecraft was a shy child; he was a retiring, almost reclusive adult much given to haunting the hours of the night. He was tall and thin, and usually almost spectrally pale, though his eyes were bright and very much alive. His jaw protruded, but his character was gentle. In his conversation, his vocabulary was revealed to be of astonishing range and instant application; his fiction, too, gives evidence of his range.

In the scarcely two decades of his writing life, Lovecraft became a master of the macabre who had no contemporary peer in America. He began to write early in life, but did not achieve publication in any national magazine until he was in his twenties. Of British ancestry, his literary influences, too, were British – Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany particularly – rather than American in the Gothic tradition of Poe, though at least one of his stories, The Outsider, might very well have been written by Poe.

Lovecraft was never widely published, and during his lifetime only one slender book appeared, a novelette printed and bound by an amateur but enthusiastic publisher. Some fifty of his stories appeared in magazines, principally Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, and Astounding Science-Fiction. He was anthologized in his native country and in England, but it was not until two years after his death that an omnibus volume containing his best prose was published by Arkham House under the title of The Outsider and Others, a book which has since become one of the most prized collector’s items in America. This volume was followed by Beyond the Wall of Sleep, Marginalia, The Lurker at the Threshold (a novel finished by August Derleth), and Something About Cats and Other Pieces, all containing lesser work.

Though his early work was more especially fantastic, influenced by Lord Dunsany, Lovecraft soon turned to themes of cosmic terror and spiritual horror in such remarkable tales as The Colour Out of Space, The Dunwich Horror, The Whisperer in Darkness, and others, among them that unique and memorable horror-tale, The Rats in the Walls, quite possibly the best of its kind written in America since 1900. Soon after his stories began to appear in the magazines, the pattern which became known as the Cthulhu Mythology became evident in his work, deriving its name from The Call of Cthulhu, the first story clearly revealing Lovecraft’s design.

That the theme of the Cthulhu Mythology had always been in Lovecraft’s mind was manifest when he wrote of his work: ‘All my stories, unconnected as they may be, are based on the fundamental lore or legend that this world was inhabited at one time by another race who, in practising black magic, lost their foothold and were expelled, yet live on outside ever ready to take possession of this earth again.’ The similarity of this pattern to the Christian mythos, particularly in relation to the expulsion of Satan and the powers of evil from Eden, is evident.

Since his death, publication of Lovecraft’s stories in America has been widespread. The majority of the stories have been published in cloth–and paper-bound collections, and millions of readers are now aware that in his untimely death America lost a singularly gifted writer in the genre of the macabre at a time when he had clearly not yet reached the fullest development of his powers. Moreover, editors of anthologies have drawn generously upon the relatively small number of stories left by Lovecraft, and the literary critics have readily acknowledged the merit of his work. ‘The best of his stories are among the best of his time, in the field he chose to make his own,’ wrote Vincent Starrett in a comment typical of the considered judgment of most critics and reviewers.

This first selection of Lovecraft’s stories to be published outside America is representative of his best work. Here are such memorable early stories as The Outsider, The Rats in the Walls, and The Colour Out of Space, which is strangely suggestive of events of our own atomic age, though it was first published in 1927; here, too, are the best of the Cthulhu Mythology short stories – The Dunwich Horror, The Thing on the Doorstep, and others. That these are the best stories H. P. Lovecraft wrote cannot be gainsaid; but they are not all the best. These stories demonstrate conclusively that H. P. Lovecraft has a secure place, however minor, in the same niche as Poe, Hawthorne, and Bierce.

August Derleth

Sauk City, Wisconsin

27 June, 1950.

The Outsider (#ulink_1fa5c01c-82ef-5e2e-ba8a-410ffb61b487)

That night the Baron dreamt of many a wo; And all his warrior-guests, with shade and form Of witch, and demon, and large coffin-worm, Were long be-nightmared. – KEATS

Unhappy is he to whom the memories of childhood bring only fear and sadness. Wretched is he who looks back upon lone hours in vast and dismal chambers with brown hangings and maddening rows of antique books, or upon awed watches in twilight groves of grotesque, gigantic, and vine-encumbered trees that silently wave twisted branches far aloft. Such a lot the gods gave to me – to me, the dazed, the disappointed; the barren, the broken. And yet I am strangely content and cling desperately to those sere memories, when my mind momentarily threatens to reach beyond to the other.

I know not where I was born, save that the castle was infinitely old and infinitely horrible, full of dark passages and having high ceilings where the eye could find only cobwebs and shadows. The stones in the crumbling corridors seemed always hideously damp, and there was an accursed smell everywhere, as of the piled-up corpses of dead generations. It was never light, so that I used sometimes to light candles and gaze steadily at them for relief, nor was there any sun outdoors, since the terrible trees grew high above the topmost accessible tower. There was one black tower which reached above the trees into the unknown outer sky, but that was partly ruined and could not be ascended save by a well-nigh impossible climb up the sheer wall, stone by stone.

I must have lived years in this place, but I cannot measure the time. Beings must have cared for my needs, yet I cannot recall any person except myself, or anything alive but the noiseless rats and bats and spiders. I think that whoever nursed me must have been shockingly aged, since my first conception of a living person was that of somebody mockingly like myself, yet distorted, shrivelled, and decaying like the castle. To me there was nothing grotesque in the bones and skeletons that strewed some of the stone crypts deep down among the foundations. I fantastically associated these things with everyday events, and thought them more natural than the coloured pictures of living beings which I found in many of the mouldy books. From such books I learned all that I know. No teacher urged or guided me, and I do not recall hearing any human voice in all those years – not even my own; for although I had read of speech, I had never thought to try to speak aloud. My aspect was a matter equally unthought of, for there were no mirrors in the castle, and I merely regarded myself by instinct as akin to the youthful figures I saw drawn and painted in the books. I felt conscious of youth because I remembered so little.

Outside, across the putrid moat and under the dark mute trees, I would often lie and dream for hours about what I read in the books; and would longingly picture myself amidst gay crowds in the sunny world beyond the endless forests. Once I tried to escape from the forest, but as I went farther from the castle the shade grew denser and the air more filled with brooding fear; so that I ran frantically back lest I lose my way in a labyrinth of nighted silence.

So through endless twilights I dreamed and waited, though I knew not what I waited for. Then in the shadowy solitude my longing for light grew so frantic that I could rest no more, and I lifted entreating hands to the single black ruined tower that reached above the forest into the unknown outer sky. And at last I resolved to scale that tower, fall though I might; since it were better to glimpse the sky and perish, than to live without ever beholding day.

H. P. Lovecraft

A collection of some of the most famous stories from the master of tomb-dark fear…A collection of some of the most famous stories from the master of tomb-dark fear…

H. P. Lovecraft Omnibus

3

The Haunter of the Dark and Other Tales

H. P. Lovecraft

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ue756693a-3cc8-52a6-939b-8e3480864d98)

Title Page (#u8775de43-5388-59c2-b39d-16c09b8f246c)

An Introduction To H. P. Lovecraft (#u0493087b-d619-5144-9fde-f980d4e0037a)

The Outsider (#u8c0b7661-0f47-5da0-b9f5-dba39e433fad)

The Rats in the Walls (#ub82e98c9-3be3-5a5b-a23d-a5113d114880)

Pickman’s Model (#u187f0307-1bd2-59f3-bfc3-479bae4171c1)

The Call of Cthulhu (#u70c33caa-f459-5530-88f8-5376e71bed18)

The Dunwich Horror (#u043261d3-d158-5a7d-a0b4-7217b3e6fe80)

The Whisperer in Darkness (#litres_trial_promo)

The Colour Out of Space (#litres_trial_promo)

The Haunter of the Dark (#litres_trial_promo)

The Thing on the Doorstep (#litres_trial_promo)

The Music of Erich Zann (#litres_trial_promo)

The Lurking Fear (#litres_trial_promo)

The Picture in the House (#litres_trial_promo)

The Shadow Over Innsmouth (#litres_trial_promo)

The Shadow Out of Time (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

An Introduction To H. P. Lovecraft (#ulink_919c3a89-d940-5535-a418-69f57419d0da)

Despite the work of such writers as Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Ambrose Bierce, America has no macabre tradition in its literature. Poe and Bierce almost alone produced a considerable body of writing in the genre; Edith Wharton, Henry James, Mary E. Wilkins-Freeman, Robert W. Chambers and a handful of others who wrote in the domain of fantasy are associated primarily with writing that is not macabre. There is not in America a collection of prose in the genre of the fantastic comparable to that produced in England by such masters as Arthur Machen, Walter de la Mare, Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany, M. R. James, E. F. Benson, May Sinclair, Marjorie Bowen, A. E. Coppard, John Collier, H. R. Wakefield, Lady Cynthia Asquith, Thomas Burke, L. P. Hartley, John Metcalfe, Margery Lawrence, and others.

It is therefore all the more interesting to note that a new generation of writers in America has turned consistently towards fantasy as a medium of creative expression. Perhaps it was the lack of any adequate outlet which dampened the ardour of prospective writers before our own time; certainly American magazines and book publishers have long been aloofly cool towards prose and poetry of the supernatural or bizarre. But with the establishment in 1923 of the magazine Weird Tales, interest in fantasy received a new impetus, and there came into modest prominence a group of writers including Clark Ashton Smith, the Reverend Henry S. Whitehead, Frank Belknap Long, Carl Jacobi, Robert Bloch, Ray Bradbury, and, surely at the head of the list, the late H. P. Lovecraft.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft, who died at forty-seven in 1937, was a native of Providence, Rhode Island, where he was a devoted student of the antiquities of that city and, perhaps by natural inclination grown from his ancestry, throughout his life a pronounced Anglophile. He led a sheltered early life, since his health was uncertain, and his semi-invalidism enabled him to read omnivorously, as a result of which the sensitive, dreamy child he was early created a strange world of his own, peopled by the creatures of his fancy. Out of this world subsequently grew much of his fiction in the realm of the supernatural.

Lovecraft was a shy child; he was a retiring, almost reclusive adult much given to haunting the hours of the night. He was tall and thin, and usually almost spectrally pale, though his eyes were bright and very much alive. His jaw protruded, but his character was gentle. In his conversation, his vocabulary was revealed to be of astonishing range and instant application; his fiction, too, gives evidence of his range.

In the scarcely two decades of his writing life, Lovecraft became a master of the macabre who had no contemporary peer in America. He began to write early in life, but did not achieve publication in any national magazine until he was in his twenties. Of British ancestry, his literary influences, too, were British – Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany particularly – rather than American in the Gothic tradition of Poe, though at least one of his stories, The Outsider, might very well have been written by Poe.

Lovecraft was never widely published, and during his lifetime only one slender book appeared, a novelette printed and bound by an amateur but enthusiastic publisher. Some fifty of his stories appeared in magazines, principally Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, and Astounding Science-Fiction. He was anthologized in his native country and in England, but it was not until two years after his death that an omnibus volume containing his best prose was published by Arkham House under the title of The Outsider and Others, a book which has since become one of the most prized collector’s items in America. This volume was followed by Beyond the Wall of Sleep, Marginalia, The Lurker at the Threshold (a novel finished by August Derleth), and Something About Cats and Other Pieces, all containing lesser work.

Though his early work was more especially fantastic, influenced by Lord Dunsany, Lovecraft soon turned to themes of cosmic terror and spiritual horror in such remarkable tales as The Colour Out of Space, The Dunwich Horror, The Whisperer in Darkness, and others, among them that unique and memorable horror-tale, The Rats in the Walls, quite possibly the best of its kind written in America since 1900. Soon after his stories began to appear in the magazines, the pattern which became known as the Cthulhu Mythology became evident in his work, deriving its name from The Call of Cthulhu, the first story clearly revealing Lovecraft’s design.

That the theme of the Cthulhu Mythology had always been in Lovecraft’s mind was manifest when he wrote of his work: ‘All my stories, unconnected as they may be, are based on the fundamental lore or legend that this world was inhabited at one time by another race who, in practising black magic, lost their foothold and were expelled, yet live on outside ever ready to take possession of this earth again.’ The similarity of this pattern to the Christian mythos, particularly in relation to the expulsion of Satan and the powers of evil from Eden, is evident.

Since his death, publication of Lovecraft’s stories in America has been widespread. The majority of the stories have been published in cloth–and paper-bound collections, and millions of readers are now aware that in his untimely death America lost a singularly gifted writer in the genre of the macabre at a time when he had clearly not yet reached the fullest development of his powers. Moreover, editors of anthologies have drawn generously upon the relatively small number of stories left by Lovecraft, and the literary critics have readily acknowledged the merit of his work. ‘The best of his stories are among the best of his time, in the field he chose to make his own,’ wrote Vincent Starrett in a comment typical of the considered judgment of most critics and reviewers.

This first selection of Lovecraft’s stories to be published outside America is representative of his best work. Here are such memorable early stories as The Outsider, The Rats in the Walls, and The Colour Out of Space, which is strangely suggestive of events of our own atomic age, though it was first published in 1927; here, too, are the best of the Cthulhu Mythology short stories – The Dunwich Horror, The Thing on the Doorstep, and others. That these are the best stories H. P. Lovecraft wrote cannot be gainsaid; but they are not all the best. These stories demonstrate conclusively that H. P. Lovecraft has a secure place, however minor, in the same niche as Poe, Hawthorne, and Bierce.

August Derleth

Sauk City, Wisconsin

27 June, 1950.

The Outsider (#ulink_1fa5c01c-82ef-5e2e-ba8a-410ffb61b487)

That night the Baron dreamt of many a wo; And all his warrior-guests, with shade and form Of witch, and demon, and large coffin-worm, Were long be-nightmared. – KEATS

Unhappy is he to whom the memories of childhood bring only fear and sadness. Wretched is he who looks back upon lone hours in vast and dismal chambers with brown hangings and maddening rows of antique books, or upon awed watches in twilight groves of grotesque, gigantic, and vine-encumbered trees that silently wave twisted branches far aloft. Such a lot the gods gave to me – to me, the dazed, the disappointed; the barren, the broken. And yet I am strangely content and cling desperately to those sere memories, when my mind momentarily threatens to reach beyond to the other.

I know not where I was born, save that the castle was infinitely old and infinitely horrible, full of dark passages and having high ceilings where the eye could find only cobwebs and shadows. The stones in the crumbling corridors seemed always hideously damp, and there was an accursed smell everywhere, as of the piled-up corpses of dead generations. It was never light, so that I used sometimes to light candles and gaze steadily at them for relief, nor was there any sun outdoors, since the terrible trees grew high above the topmost accessible tower. There was one black tower which reached above the trees into the unknown outer sky, but that was partly ruined and could not be ascended save by a well-nigh impossible climb up the sheer wall, stone by stone.

I must have lived years in this place, but I cannot measure the time. Beings must have cared for my needs, yet I cannot recall any person except myself, or anything alive but the noiseless rats and bats and spiders. I think that whoever nursed me must have been shockingly aged, since my first conception of a living person was that of somebody mockingly like myself, yet distorted, shrivelled, and decaying like the castle. To me there was nothing grotesque in the bones and skeletons that strewed some of the stone crypts deep down among the foundations. I fantastically associated these things with everyday events, and thought them more natural than the coloured pictures of living beings which I found in many of the mouldy books. From such books I learned all that I know. No teacher urged or guided me, and I do not recall hearing any human voice in all those years – not even my own; for although I had read of speech, I had never thought to try to speak aloud. My aspect was a matter equally unthought of, for there were no mirrors in the castle, and I merely regarded myself by instinct as akin to the youthful figures I saw drawn and painted in the books. I felt conscious of youth because I remembered so little.

Outside, across the putrid moat and under the dark mute trees, I would often lie and dream for hours about what I read in the books; and would longingly picture myself amidst gay crowds in the sunny world beyond the endless forests. Once I tried to escape from the forest, but as I went farther from the castle the shade grew denser and the air more filled with brooding fear; so that I ran frantically back lest I lose my way in a labyrinth of nighted silence.

So through endless twilights I dreamed and waited, though I knew not what I waited for. Then in the shadowy solitude my longing for light grew so frantic that I could rest no more, and I lifted entreating hands to the single black ruined tower that reached above the forest into the unknown outer sky. And at last I resolved to scale that tower, fall though I might; since it were better to glimpse the sky and perish, than to live without ever beholding day.